A Lesson Never Too Late For the Learning

By David McGee

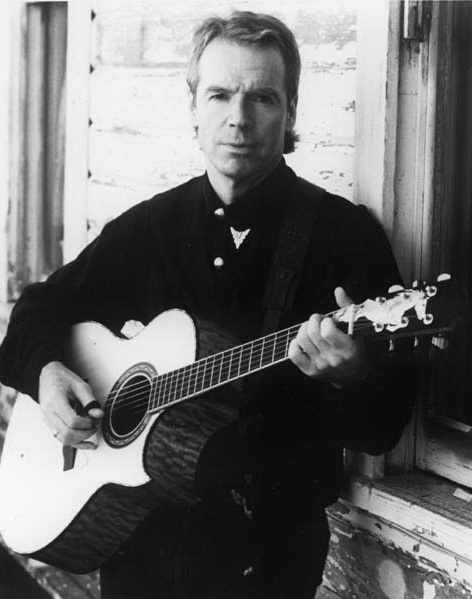

Danny O'Keefe: Making sense of a lifetime's worth of emotions

IN TIME

Danny O'Keefe

O'K Records

Danny O'Keefe would probably be the first to say life has been good to him, even if the bald facts of late might lead others to be skeptical of such a claim. In 2005 he was in Nashville, preparing to start recording a new album when Hurricane Katrina leveled New Orleans. As he and the rest of the world watched the unfolding horror in the Crescent City and our government's tepid response to it, O'Keefe found his singing voice deserting him, followed by a plague of ocular migraine headaches, followed by doctors finding a growth on his thyroid gland. Reeling from the news of disasters both natural and personal, O'Keefe, who has given American popular music one of its enduring classics in his 1972 Top 10 single, "Good Time Charlie's Got the Blues"—a tune covered by everyone from Elvis Presley to Maria Muldaur to Willie Nelson to Waylon and who knows how many others—was, shall we say, given to reflection. The album he began back then in those dark days for our country and for him is now complete and just about perfect in all dimensions. For someone who basically lost his voice, O'Keefe, now 65, still sings in the light, affecting, slightly blues-inflected tenor that made his version of "Good Time Charlie" so endearing and irresistible, but also demonstrates an understandably greater sensitivity to the nuances of his lyrics. As for those lyrics, O'Keefe collaborated with several redoubtable songwriters on all but one of the album's dozen cuts, but everyone's on the same page with regards to subject matter, which breaks down by and large to poignant reminiscences of the past and tender evocations of a deep love unfolding here and now, and at long last appreciated for what it brings to a life. In the eight years since his previous album release, Danny O'Keefe has lived a lifetime's worth of emotions, it appears, and is now in a place where he can make sense of it all.

And how beautifully he does that. With the assistance of producer Mick Conley, O'Keefe has fashioned a gentle masterwork defined by its reliance on acoustic instruments (you'll hear some subdued twanging electric guitar—as on the tender, soothing love song, "Sleep [Anywhere On Earth You Are]"—here and there, but it's rare, as are the discreetly employed synthesized strings) and a wee small hours, small jazz combo feel that reaches its apex on the laconic lament, "Last Call," on which an uncredited harmonica player is conjuring up the richest sort of lonely, lights-out ambiance imaginable as O'Keefe drawls a cutting reminder that "there ain't no happy endings to the blues." In O'Keefe's laid-back crooning style you can hear an affect Michael Martin Murphey picked up on post-"Wildfire" that served him so well during his Capitol pop-country balladeer years, and in his piano-based ballads and conversational lyrics you hear the inspiration for a dedicated song craftsman such as Marc Cohn, too. Most important, you hear an artist in full command of all his gifts.

But the song's the thing, and these dozen are superb. It's hard to figure out which ones to recommend most and even harder not to resort to simply quoting the telling lyrics ad infinitum, so many leap out and connect with the listener's heart on a fundamental level. Two themes emerge, and those are stated in the album's first and last songs: "Treat every time like the first" and "Love is still the sacred shrine/where hearts forever kneel," are the key lyrics from "The First Time" and "A Bedtime Story," respectively. On the scoreboard, said themes pretty much play to a tie here, depending on one's interpretation, and both make strong cases for themselves. In his post-Katrina ruminations, O'Keefe seems to have gained a greater appreciation—haven't we all?—for the fleeting nature of, well, everything. With that comes evidence of a newfound determination to embrace the moment, seize the day, if you will. In the album opener, the loping, mandolin-spiked country ballad, "The First Time" (does anyone else hear echoes of "Good Time Charlie" in this?), he issues the aforementioned advisory, "Treat every time like the first time," while recounting a number of firsts he overlooked in a failed romance, but the larger import of his words resonates throughout the ensuing songs. Time is a constant traveler here. In the comforting, organ-enhanced shuffle of O'Keefe's "Maybe Next Time," he finds solace for new love in the thought that "maybe next time is still a place/we haven't come to yet," and offhandedly muses, "Love will keep you running/out of time and space," kind of laying that metaphysical bombshell on you as if it's conventional wisdom. Collaborating with the estimable Beth Neilsen Chapman on the "Back In Time," its stark fingerpicked acoustic guitar backing producing a contrasting bright, uplifting melody, O'Keefe charts time's inevitable march, from childhood memories ("the screen door slams, a voice grows faint/it's the little things that haunt you/back in time...") into familial history, when succeeding generations view you, know you, only as "photos in a family book/windows on eternity/where children learn to pause and...look/back in time..." Against this backdrop, it's fitting that O'Keefe, writing alone, should reserve for himself his harshest, most piercing judgment of his aimless, thoughtless behavior. In "Missing Me," all graceful rolling hills of guitar-piano-bass rhythm, O'Keefe admits to a haunting disconnect from his own essence, spiritually and artistically: "I miss all the things I used to love to do/times I spent with others/times I spent with you/I miss those magic moments turned into songs/I miss all the rights turned into wrongs/And I miss you/that's a given...once an arrow always aiming/now I'm a target too/missing me lately, baby, more than I been missin' you."

Even as missed opportunities and a tardy understanding about their meaning bedevil him, O'Keefe still has plenty of room in his heart to give abundantly and unconditionally when the real thing comes along. In the jazzy ballad "Alone In the Dark," written with Jay Gruska, O'Keefe posits his love story in cinematic terms, skirts cornball territory as artfully as Tom Waits and winds up with a warm-hearted winner when he sings plaintively and with utter sincerity, "If I could put my life on film, you would be the star/and the world would see my vision of how wonderful you are/I'd put you in the pictures you're always dreaming of/If I could make a movie of our love." It's probably not an accident of sequencing that another captivating love song follows this one, in this instance the gentle, lilting "When You Come Back Down," written with Tim O'Brien, who, Lord knows, has been for a few years now writing some of the best original songs of any tunesmith in our land. This lovely country-inflected beauty lopes along soothingly, and O'Keefe simply caresses the lyrics straightforwardly, in a voice direct and deeply engaged in showing off the singer's open heart, especially when the song lifts into its touching bridge, "Your memory's the sunshine every new day brings/I know the sky is calling/Angel let me help you with your wings," at which point an evocative slide guitar solo ascends ahead of another lovely chorus. The final song, "A Bedtime Story," returns us to where we began this journey, with O'Keefe, backed mostly by a lone piano, reflecting over time, as he did at the outset, marveling at what's been wrought with the passing of the years and at the persistence of love through it all, but now without regrets, now having passed through the crucible of experience to emerge whole in spirit, blessed with renewed purpose born of understanding: "Let's ride the waves beneath our dreams and wake the ones above/and by our love of freedom be fulfilled by the freedom of our love," he implores, ahead of the benediction—"Love is still the sacred shrine/where hearts forever kneel." Therein lies a lesson never too late for the learning. In time, perhaps we will.

Buy it at www.CDBaby.com

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024