Anything For Billy

(But a Pardon)

Former Florida Governor Charlie Crist got into some hot water when, before turning over the keys to the mansion to incoming Governor Rick Scott—referred to by Huffington Post’s Jason Linkins as “The Lizard King of fraud”—he secured the Florida Board of Clemency’s approval of a pardon for Jim Morrison, who was convicted of two misdemeanor charges following a concert in Miami in 1969. The pardon was denounced by surviving Doors members and Morrison’s widow, Patricia Keneally, with both parties insisting the provocative Doors singer did nothing to warrant his arrest in the first place.

Half a continent away, outgoing New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson elicited more praise than condemnation—although he did stir up passions—for his refusal to issue a posthumous pardon to the bloodthirsty outlaw Billy the Kid. Back in 1879, territorial governor Lew Wallace (author, by the way, of Ben Hur) had promised the Kid amnesty for murders he had committed if the young gun would testify before a grand jury about a killing he had witnessed. The Kid made good on his end of the bargain, Wallace reneged.

“If one has to rewrite a chapter as prominent as this, there had better be certainty as to the facts, the circumstances and the motivations of those involved,” Richardson announced, adding he would not alter the history of a man who spent his life “pillaging, ravaging and killing the deserving and the innocent alike.”

Pat GarrettAmong those who were actively politicking the Governor to deny the pardon were descendants of Sheriff Pat Garrett, a one-time buddy of the Kid’s who killed him in 1881. Three Garrett grandchildren and two great-grandchildren spoke out against the pardon, as did Lew Wallace’s great-grandson William Wallace. In an email to a New York Times reporter, Susannah Garrett, the Sheriff’s granddaughter, wrote, “Best to leave history alone. My he rest in peace.”

Richardson did the right thing, because Billy the Kid was no damn good. In a September 6, 2010 report in the New York Times, author and New Mexico resident Hampton Sides framed the argument thusly: “But regardless of whether he got a raw deal, the Kid was a thug. He murdered one of Garrett’s predecessors and as many as eight other people. He rustled horses and cattle. Far from heroic, the Lincoln County War was just a feud over beef contracts, and it marked one of the bleakest episodes in the history of the West.”

So who was Billy the Kid? For one, he was indeed the thug Hampton Sides declares him to be. But Sides didn’t know the Kid or anyone who knew the Kid, and his dismissal of the Lincoln County War as “just a feud over beef contracts” ignores, as is easy to do from the vantagepoint of our time, how serious were those “beef contracts” and the power such legalities conferred on the rival gangs (Murphy-Dolan and Tunstall-McSween) shooting it out for supremacy in the territory. For that we turn to a chapter from a classic of Old West reporting, the 1926 book penned by Walter Noble Burns, The Saga of Billy the Kid. In his introduction to the 1999 republication of Burns’s book, Richard W. Etulain, professor of history and the director of the Center for the American West the University of New Mexico, where he has taught since 1979, describes Burns as “the most significant of these journalist-historians. His The Saga of Billy the Kid did more than any of the other biographies to influence the Wild West histories that appeared during the interwar years. A Chicago newspaperman since the turn of the century, Burns had written on a variety of historical, biographical and literary subjects including Wild Bill Hickok, before he came to New Mexico in 1923 to research the story of Billy the Kid. An indefatigable researcher, an ambitious interviewer, and a stunning storyteller, Burns crisscrossed the state for three months, taking oral histories from most of the well-known survivors of New Mexico’s Lincoln Country War of the late 1870s. He also skimmed newspaper stories of the 1870s and 1880s and read some of the previous accounts of Billy and the war.”

So for a window into the Billy the Kid story from the most contemporaneous source available we go to Walter Noble Burns’s The Saga of Billy the Kid.. (Pat Garrett’s self-aggrandizing 1882 ghostwritten Pat F. Garrett’s The Authentic Life of Billy the Kid is simply an unreliable document, more fiction than fact, and something of a PR stunt on Garrett’s part.) This excerpted chapter, “Child of the Dark Star,” is a straightforward telling of how young William H. Bonney, born in New York City, arrived in New Mexico and set out on his outlaw course. Billy’s first killing, as a means of avenging an insult to his mother, occurs herein and it gets bloodier and more cold-blooded from there. The most benign story is how Billy Bonney came to be known as Billy the Kid. Fascinating stuff, even the stuff of legend, but not of pardon.

This being America, though, every defendant is due his or her day in court, and so it is with Billy the Kid. The likes of Hampton Sides may tar him with a broad brush as a “thug,” and dismiss the import of the Lincoln Country war, but Walter Noble Burns, based on interviews he conducted with people who knew the Kid and observed him in and out of skirmishes, regarded his subject in the fullness of his life and character.

Burns: “But in fairness to Billy the Kid he must be judged by the standards of his place and time. The part of New Mexico in which he passed his life was the most murderous spot in the Wet. The Lincoln County war, which was his background, was a culture-bed of many kinds and degrees of desperadoes. There were the embryo desperadoes whose record remained negligible because of lack of excuse or occasion for murder; the would-be desperado who loved melodrama; and the desperado of genuine spirit but mediocre craftsmanship whose climb toward the heights was halted abruptly by some other man an eighth of a second quicker on the trigger. All these men were as ruthless and desperate as Billy the Kid, but they lacked the afflatus that made him the finished master. They were journeymen mechanics laboriously carving notches on the handles of their guns. He was a genius painting his name in flaming colors with a six-shooter across the sky of the Southwest.

“With his tragic record in mind, one might be pardoned for visualizing Billy the Kid as an inhuman monster reveling in blood. But this conception would do him injustice. He was a boy of bright, alert mind, generous, not unkindly, of quick sympathies. The steadfast loyalty of his friendships was proverbial. Among his friends he was scrupulously honest. Moroseness and sullenness were foreign to him. He was cheerful, hopeful, talkative, given to laughter. He was not addicted to swagger or braggadocio. He was quiet, unassuming, courteous. He was a great favourite with women, and in his attitude toward them he lived up to the best traditions of the frontier.

“But hidden away somewhere among these pleasant human qualities was a hiatus in his character—a suz-zero vacuum—devoid of all human emotions. He was upon occasion the personification of merciless, remorseless deadliness. He placed no value on human life, least of all upon his own. He killed a man as nonchalantly as he smoked a cigarette. Murder did not appeal to Billy the Kid as tragedy; it was merely a physical process of pressing a trigger. If it seemed to him necessary to kill a man, he killed him and got the matter over with as neatly and with as little fuss as possible. In his murders, he observed no rules of etiquette and was bound by no punctilios of honour. As long as he killed a man he wanted to kill, it made no difference to him how he killed him. He fought fair and shot it out face to face if the occasion demanded, but under other circumstances he did not scruple at assassination. He put a bullet through a man’s heart as coolly as he perforated a tin can set upon a fence post. He had no remorse. No memories haunted him.”

For refusing to pardon this engaging sociopath, Gov. Richardson, you done good. —David McGee

Walter Noble Burns’s The Saga of Billy the Kid is available at www.amazon.com***

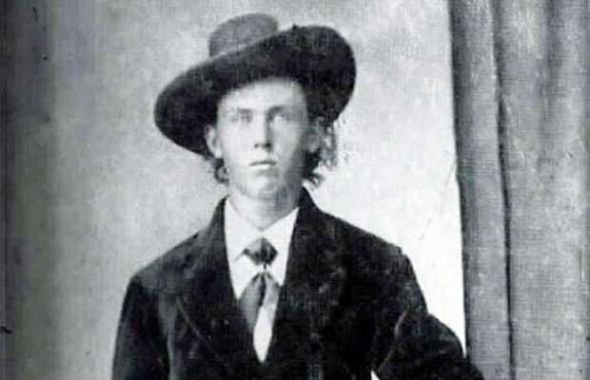

Billy the Kid, born William H. Bonney in New York CityChild Of The Dark Star

The foregoing tales may be regarded, as you please, as the apocryphal cantos of the saga of Billy the Kid. They are not thoroughly authenticated, though possibly they are, in the main, true. Most of them are perhaps too ugly to have been inventions. If you are skeptical, your doubt may be tempered by the fact that they have at least always gone with the legend and have such authority as long-established currency may confer.

By Walter Noble burns

Excerpt from The Saga of Billy The KidThroughout his life of bold adventure, Billy the Kid’s name was lost in his pseudonym. His name really doesn’t matter much; by any other he would have shot as straight; but it happened to be William H. Bonney, and he was born in New York City, November 23, 1899. William H. and Kathleen Bonney, his parents, both of unknown antecedents, emigrated in 1862 to Coffeyville, Kansas, taking with them three-year-old Billy and a baby brother named Edward.

When little Billie Bonney was toddling about its streets, Coffeyville was a mere collection of shacks on an obscure frontier, safely to one side of the fighting in the Civil War, which was then in full swing. All that is known of the Bonneys in the little Kansas town is that Billy’s father died and was buried there. Soon afterward, the widow with her two children moved to Colorado.

Colorado in those days was the ultimate West, being beyond the Great American Desert, vaguely celebrated as a land of gold through the Pike’s Peak mining stampede of a few years before; Denver ,the principal town, contained only three thousand people, and communicated with the outside world by pony express which carried the mail at twenty-five cents an ounce to Leavenworth in ten days. How Mrs. Bonney made the trip across the plains, or in what town in Colorado she located, is not of record; but in whatever town it was, she married a man named Antrim and soon set out for Santa Fe, the centre of the ancient Spanish civilization along the upper reaches of the Rio Grande.

Marty Robbins, ‘Billy the KidBy wagon the little family must have gone, following the mountain route of the Santa Fe trail, through the Mexican adobe village of Trinidad on the River of the Lost Souls, over Raton Pass into New Mexico; and it is easy to fancy little Billy opening his eyes in amazement as almost over his head towered the four-square battlements of Fisher’s Peak, uniquely beautiful among mountains, with the flat-topped Ratons stepping down the horizon in a series of tablelands. Yonder in the north rose the twin summits of the Spanish Peaks; and along the southwestern sky tumbled the white chaos of the Sangre de Cristo, Blood of Christ Mountains, named by the early padres when their eyes visioned the eternal snows crimsoned by the sunset. Pine forests clothed the slopes; the valleys were deep bowls of misty purple; and the rough wagon road hung against granite walls and skirted precipices, with a thousand-foot drop a few inches to one side, just as the broad motor boulevard over the pass does to-day.

Billy and his mother come out a little more definitely on the canvas after their arrival in Santa Fe. The boy was five years old then and lived in the quaint old city three years, during which time his mother kept a boarding house. A few old-timers remember the child to this day, a lively gamin playing in the streets with the Mexican children, shooting marbles in the purlieus of the haunted old Palace, spinning tops on the ground hallowed by pioneer padre and conquistador; trailing Kit Carson about the streets with other little ragamuffin hero-worshipers whenever the famous old scout and Indian fighter rode into town from his home in Taos, ninety miles away, feasting his eyes on the solemn pomp of religious fiestas and processions, and thrilling to the prairie-schooner caravans that drove in every summer over the Santa Fe trail to fill the ancient plaza with the stir and excitement of strange romance.

The Antrims moved in 1868 to Silver City in southwestern New Mexico, a silver camp in its raw boom days. Here Antrim worked in the mines; his wife opened another boarding house. Billy, who was eight years old upon their arrival, went to school. Ash Upson, one of Mrs. Antrim’s boarders, has left his testimony that Billy was bright at his lessons and stood well in his classes. “he had as a little boy,” says Upson, “a happy, sunny disposition but also a fiery temper, and when he was in one of his rages nobody could do anything with him.”

‘Billy became an adept at dealing stud poker and monte, learned to stack a deck, deal from the bottom, palm a card, and cheat a fellow gamester’s eyes out without detection. In a little while he was master of all the dextrous stratagems of the crooked short-card gambler. This at an age when boys in less strenuous communities are still at tops and marbles.’For four years Billy lived here in Silver City, growing into precocious youth. The town was uncouth and lawless, filled with saloons and gambling houses, bad Mexicans, and worse white men. It was the devil’s own school for any boy, and Billy leaned its lessons well. He associated on familiar terms with the wild spirits of the place, hung about saloons, watching the gamblers at their games, and soon displayed a natural and uncanny facility at cards. To a boy of such talent, gamblers good-naturedly condescended to teach their tricks. Under their expert coaching, Billy became an adept at dealing stud poker and monte, learned to stack a deck, deal from the bottom, palm a card, and cheat a fellow gamester’s eyes out without detection. In a little while he was master of all the dextrous stratagems of the crooked short-card gambler. This at an age when boys in less strenuous communities are still at tops and marbles.

It was at Silver City, when twelve years old, that Billy killed his first man. His mother with Billy at her side was on her way from home into the business section to do some shopping. Picture the couple if you will: the mother in her plaid gingham and sunbonnet, her face kindly, honest, rather sad, according to descriptions; the lad slender, alert, swinging along with brisk, vigorous step, maturely wise gray eyes. A group of men lounged in front of a saloon, a young blacksmith among them, with some reputation in town as a rough character and bully. As Billy and his mother passed, the smith perhaps half-tipsy, dropped some light remark, directed, possibly with flirtatious intent, at Mrs. Antrim. In his eyes, the boy was negligible. But Billy flamed at once into violent passion and resentment, picked up a stone, hurled it with all his might at the head of the insulter of his mother. The missile knocked off the blacksmith’s hat; an inch or two lower and it would have caught him full in the forehead and probably have killed him. Unhurt but blazing with anger, the fellow rushed at Billy, who dodged away into the street. A man named Moulton was standing at the curb; as the blacksmith lurched past, Moulton knocked him down with his fist, and when he arose, knocked him down again. Which rough chivalry, in keeping with the spirit of the mining camp, saved Billy from chastisement and, for the time being, closed the incident.

Charlie Daniels Band, ‘Billy the Kid’On an evening a few weeks later, Moulton was refreshing himself with a glass of beer in Dyer’s saloon on the main street. It was a quiet night; a few stragglers at the bar; the faro games and monte layouts along the opposite wall doing a fair business. The young blacksmith was sitting in at a poker game in a corner; Billy Bonney was leaning against the ice box, idly observant.

Two drunken fellows blundered in off the street through the swinging doors and one, in drunken humour, with a full-arm swing, knocked Moulton’s hat off his head. There was doubtless merry intent in the joke, but Moulton, bent upon the quiet enjoyment of his beer, failed to enter into the sprit of and with a blow of his fist stretched the jester on the floor. Thereupon the other man took up the quarrel and in a moment the prostrate fellow having regained his feet, a furious three-cornered fight was in full swing, with Moulton hard-pressed but holding his own.

The blacksmith saw in the situation an opportunity for revenge. Still smarting from the drubbing he had previously received, he sprang from his seat, raised his heavy chair high in the air, and aiming at the back of Moulton’s head, brought it down with smashing force. The blow failed of its target; struck glancingly against Moulton’s shoulder. With this new adversary in action, Moulton, fighting one against three, was in danger. But Billy Bonney no longer leaned idly against the ice box. He, too, saw an opportunity for revenge and an opportunity also to render assistance to a friend in distress—a friend who had been his champion when he had needed aid and to whom he owed a debt of gratitude. Whipping out his pocketknife, he rushed upon the blacksmith just as that ruffian, again, swinging the chair aloft, was in the arc of delivering a second blow to Moulton. Three times the boy struck with his blade; down fell the chair, clattering against the bar; the blacksmith, staggering back, clutched at his heart, pitched headlong.

So, for the first time, the wolf cub tasted blood.

***

Aaron Copland’s ‘Billy The Kid’ Orchestral Suite 1938

Aaron Copland, ‘Billy the Kid’ Orchestral Suite, Part 1

Aaron Copland, ‘Billy the Kid’ Orchestral Suite,’ Part 2

Aaron Copland, ‘Billy the Kid’ Orchestral Suite,’ Part 3Another pragmatic basis for the development of Copland's forthright "American sound" can be found in the contexts for which he was writing. It was largely in tandem with collaborative projects involving specifically American subject matter, in the genres of ballet, theater, and film, that Copland evolved this sound. Billy the Kid marked a significant breakthrough, paving the way for the later ballets. Within a year of its premiere in 1938, he had made his entrée into writing film scores as well. The composer himself wrote that he approached the prospect of this "folk-ballet" with "a firm resolve to write simply," believing that as part of a stage work, "music should play a modest role, helping when help is needed, but never injecting itself as if it were the main business of the evening."

Yet in the process, Copland produced music that has indeed held its own as a beloved concert staple. The familiar orchestral Suite extracts some two-thirds of the original ballet score. The ambitious young impresario Lincoln Kirstein (1907-1996) had proposed the idea of Billy the Kid for his newly formed Ballet Caravan, a touring company that was a forerunner of the New York City Ballet. Playing a sort of American Sergei Diaghilev, Kirstein fixed on Copland as his Stravinsky, intent on establishing an indigenous ballet distinct from Franco-Russian traditions.

Billy the Kid was designed as a one-act ballet based on a semi-fictional treatment of the notorious outlaw, with choreography by Eugene Loring. Born Henry McCarty (1859?-1881)—a.k.a. William H. Bonney—Billy appears as a quasi-mythical figure, a romanticized emblem of the passions and dangers of the Wild West. Copland frames the story with widely spaced harmonies that vividly conjure a sense of the open prairie (along with its loneliness) and the vast scale of migration westward.

"Street in a Frontier Town," the most extensive section of the Suite, where we first encounter Billy as a boy of twelve, cleverly recomposes bits of cowboy tunes in a way that adds much more than "flavor." Copland essentially devises his own version of the montage technique Stravinsky had used for the crowd scenes in Petrushka to suggest the lively scene of the Southwest town. For example, he adds unexpected harmonic colorings and clashes of key, while metrical asymmetries and cross-rhythms build excitement until the scene erupts in chaos. During a drunken brawl, Billy witnesses his mother accidentally being shot in the crowd and instantly stabs those responsible. This sets the pattern for Billy's criminal career as an adult. The ballet then jumps to representative episodes. "Card Game at Night" establishes a lonely, reflective mood "under the stars." In dramatic contrast, violence erupts once more in the percussion-heavy "Running Gun Battle" as Billy is ambushed by his former friend, Sheriff Pat Garrett. In a local saloon, complete with out-of-tune piano, a tipsy crowd celebrates the outlaw's capture. The Suite omits the ballet's episode of Billy escaping from jail into the desert, where he romances his sweetheart, but cuts to the scene of Billy's death after he has been caught for the last time. A reorchestrated version of the opening prairie music—looking ahead to the bold rhetoric of the Fanfare for the Common Man—is meant, observes Copland, "to convey the idea of a new dawn breaking."—courtesy The Kennedy Center

***

It is perhaps worth noting that this unpretty barroom tragedy—the first murder in Billy the Kid’s long list—was hall-marked by a native expertness in deadliness. No veteran of crime could have done the thing more deftly. Here was a child, at least in years, who had never taken a human life before and probably had never remotely considered such a contingency. But when a problem arose which, it seemed to him in an instinctive flash, only murder could solve, he solved it with murder without a moment’s hesitation. The soul of this infant, only just out of swaddling clothes, seemed plainly no boy’s soul, but rather that of a man with a background of crime already achieved; a soul out of the frozen dark ages, charged with a heritage of sinister sophistication.

With his victim dead at his feet, Billy darted out the door and, slinking through the back streets and alleys, made his way home, his only thoughts now upon escape. Possibly a vague vision of the gallows or prison arose before him. He would not wait for arrest; he would take no chances on suffering any penalties for his deed. His mind was made up. He would flee from Silver city, hide out in the mountains, put distance between him and the law, find refuge beyond the horizon, somewhere, anywhere. He went to his mother’s room, told her he had killed the man who had insulted her; not boastfully, not yet regretfully, dealing coldly with a fact. Heretofore we have had dim pictures of this mother in the humdrum of prosaic existence. Here was her crisis, and in the revealing light of it she stands out a Spartan. She shed no tears; it was no time for tears. She thought only of the safety of her first-born. She agreed with his plan to dodge arrest; gave him the few dollars she had on hand; drew him to her bosom for the last time and kissed him good-bye. The boy slipped out into the night, his mother’s eyes straining after the slight, furtive figure hurrying away, growing dimmer and dimmer, fading out at last in the darkness. It was the final parting on earth; mother and son never saw each other again.

A letter from Wm. H. Bonney to Territorial Governor Lew Wallace, dated March 1881.

‘Dear Sir: I wish you would come down to the jail and see me. It will be to your interest to come and see me. I have some letters which date back five years and there are Parties who are very anxious to get them but I shall not dispose of them until I see you. that is if you will come immediately. Yours Respect, Wm. H. Bonney’For the next four years we know little of the details of Billy Bonney’s career. He got finally into Arizona where he evolved through hard experience into an expert cowboy. He worked on various cattle ranches and for various cattle outfits between the Mogollon Mountains and the Mexican boundary and at odd times was in and out of Bowie, Tuscon, Benson, Nogales, Bisbee, the Gila River villages. It was a sparsely settled country of mountains, deserts, and open range; a dangerous country, too, with the Apaches murdering and raiding at will; and as wild and turbulent as could be found in all the West even in that early day.

Billy reappears definitely upon the stage at the age of sixteen. From this time on, his career gallops swiftly. He was now a well-grown boy, almost as tall as he ever became, lean, full of restless energy; a happy-go-lucky youth, irresponsible, unhampered by moral scruples of any kind, capable of smiling murders; in appearance and manner, as innocuous as a sucking dove, but as poisonously dangerous as a bull rattlesnake.

While hanging about Fort Bowie in southeastern Arizona, dealing monte and living precariously, he picked up a partner of unknown name but who, doubtless, in dodging the law here and there about the country, had borne many names and who at this time passed under the suggestive nickname of “Alias.” Bound for the San Carlos reservation, three Indians camped at the military post, fresh from a hunting and trapping expedition in the Chiricahui Mountains. They had in their possession eight valuable packs of fur pelts, twelve ponies, good saddles, firearms, and blankets, which aroused the cupidity of Billy and Alias, the cards having run against these two of late, leaving them practically penniless. Learning the trail the Indians would take out of the fort, Billy and his partner went ahead on foot a few miles and lay in ambush. When the redmen came jogging along on their ponies, Billy stepped out and with three shots toppled them out of their saddles dead in the road. Stopping only long enough to drag the bodies out of sight into the underbrush, Billy and his companion, now well armed and mounted, headed to the south with their plunder. They sold everything except the horses they were riding and the weapons they had appropriated for their personal accoutrement to a party of freighters in the Dragoon Mountains, and, with well-filled pockets, made their way to Tucson, where they enjoyed themselves on the proceeds of their adventure. Alias steps out of the story here; Billy remained in Tucson for an undetermined period, living by his wits and his nimble fingers at cards and becoming a familiar figure in the sporting element of the town, which at that time was the dominant portion of the population.

While in Tucson, Billy killed another man over a card game. Nothing more is known about it: neither the name of the man nor any single circumstance. Doubtless, the tragedy at the time rang through the town; the picture of it grips the imagination: the electric hush that broods over a card game; a sudden quarrel; anger flaming into high words; a shot; a dead man sprawled on the floor; something dark slowly spreading about him. Who knows what human history was behind this man? Here was the end of ambition, passion, striving; some mother had loved him; the tenderness of home was in his story somewhere. A big thing in its moment, this old-time tragedy; now it is forgotten, every detail of it lost in dead, hopeless silence. “Billy killed another man” is all the history of it; an epic of life and death packed in four words.

‘Me and Billy the Kid, we never got along/I didn’t like the way he buckled his belt/and he wore his gun all wrong/he was bad to the bone/all hopped up on speed/I would have left him alone/if it weren’t for that senorita…’—Joe Ely, ‘Me and Billy the Kid’Also Billy killed a Negro soldier in those early days. This seems rather definitely established. According to the story, Billy caught the Negro cheating at cards. But no more is known of this murder than of the other in Tucson; not even where it occurred. It is supposed to have been at an army post, but at which one remains a question. Some of the stories locate it at Fort Union, New Mexico. This seems improbably, as, except for this vague ascription, there is nothing to indicate that Billy at this phase of his career was ever anywhere near Fort Union, which was up in the Mora country northeast of Las Vegas.

Billy slipped across the border after these affairs into old Mexico. While knocking about Sonora, he fell in with Melquiades Segura, a young gambler as ready as he for any escapade. These two, pooling their capital, opened a monte bank in Agua Priera. Bucking the game, José Martinez quarreled with Billy, who was dealing. Both reached for their guns, Billy was the quicker and Martinez fell dead across the gambling layout.

Behold thereafter Billy and Segura galloping by moonlight over Sonoran sagebrush steppes, across the Sierra Madre range into Chihuahua. Southward past Casas Grandes they rode through the same country which in years later saw Pancho Villa and his bandit raiders go up to the sack of Columbus. Their destination was Chihuahua City, painted alluringly by Segura as a good gambling town, offering fat pickings, and here the two adventurers finally fetched up. Chihuahua, living up to its reputation, proved such a good gambling town that Billy and Segura soon lost their bank roll.

Followed then a series of street robberies which set the old town buzzing. Prosperous Mexican gamblers were accustomed toward morning to take home the receipts of the night’s play in buckskin bags carried by their mozos. Billy and Seguar found it child’s play to step from some dark doorway and at the point of their revolvers relieve the gamblers of their bags of dollars and doubloons. One gambler, however, resisted, and Billy took his life as well as his money; and before daybreak, on stolen horses, Billy and Segura were riding hard for the Rio Grande, three hundred miles away.

Once more in New Mexico and parted from Segura, Billy met Jesse Evans, a few years older than himself, living also by his wits and his six-shooter. Though later to fight with the Murphy faction against Billy in the Lincoln Country war, Jesse Evans seems to have held the highest place in Billy’s esteem of all the comrades of these early years. Quite worthy, too, of the young daredevil’s friendship, this dashing Texas cowboy might seem to have been. He was a crack rider, crack shot, gambler, rustler, highwayman, heading as straight as might be for the penitentiary where he eventually landed, but on the way, taking life merrily, worrying not at all about the future, and riding “high, wide, and handsome.”

These two scape grace men-at-arms wandered together through the border country, rustling stock occasionally, taking a whirl at cards, sharing the luck of fat and lean days. If perchance their fortunes were at low ebb, they had but to drive a few stolen steers to market. Then logically to a faro bank where they might heel a bet from the queen to the ace or copper a stack on the deuce. If they won, the world was their for at least twenty-four hours; if they lost, there were plenty of streets on the range. Of the adventures that befell them only one has survived in dubious tradition. Somewhere between the san Andreas Mountains and the Guadalupes, it is said, they broke bread one day with a party of immigrants, three men, three women, and several children. After they had taken their departure, a band of Apaches swooped out of the hills and attacked the camp. Riding back, Billy and Jesse opened fire with their rifles upon the savages, who wre finally driven off, leaving eight dead on the field. During the fight, an Indian bullet shattered the stock of Billy’s rifle and another knocked off the heel of one of his boots. One of the immigrants received a wound through the stomach from which he died and two others were shot, thought not dangerously.

Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid, directed by Sam Peckinpah, 1973, featured Bob Dylan, acting and on the soundtrack, singing his ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’Billy and Jesse joined fortunes with Billy Morton, Frank Baker, and Jim McDaniels, cowboy friends of Evans, in the summer of 1877 around Mesilla, and remained with them for a time. In camp-fire talk, McDaniels once made passing allusion to Billy.

“Who?” asked Evans, not hearing the name.

“Billy,” replied McDaniels and added by way of indubitable identification, “the Kid.”

There was a certain hard staccato music in the words that appealed to McDaniels and he rolled the name he had inadvertently coined over his tongue again and again—“Billy the Kid, Billy the Kid.”

So a famous name was born casually. Nothing original about it; but it had a quaint ring that caught the fancy of the other cowboys, and from that time on Billy Bonney was Billy the Kid to them and the rest of the world.

Mexicans sometimes changed the epithet into the Spanish equivalent, “El Chivato.” But they usually took no more liberties with the name than with the Kid himself; it remained with them and their descendants “Billee the Keed.” Thousands of youngsters have been called “Billy” since then in that part of the country, and thousands have been referred to as “the Kid.” But in combination, the words have a single connotation. For the Southwest there has never been but one Billy the Kid.

When his four companions set off eastward for the Pecos, Billy remained in Mesilla; there was a little matter which required his personal attention. It was as well for Morton and Baker, as they shook his hand in parting, that they could not read the future. Within less than a year, Billy the Kid was to snuff out both their lives.

Woody Guthrie, ‘Billy the Kid’ (1944)Word had reached Billy that his former comrade, Segura, was in jail in San Elizario in Texas, eighty miles away, and he determined on a daring coup to save him. With plans carefully laid, he set out on his pony late in the afternoon for a Paul Revere dash to the Rio Grande. It was fifty-five miles from Mesilla to El Paso; Billy had covered the distance before midnight. By three o’clock in the morning, he was in San Elizario. The little town on the river band was asleep. Hiding his pony in an alley, Billy slipped through the dark streets to the jail. He thumped boldly on the door. A fat Mexican jailer, startled from slumber on an office cot, shuffled across the floor.

“Quien es?” he called gruffly.

“Texas Rangers,” answered Billy in Spanish. “Open up. We have two American prisoners.”

There was a rattlings of keys on the inside; the door swung cautiously open. Billy pushed in; at the same time shoving the barrel of his six-shooter into the paunch of the astonished Mexican official.

“Hands up!” he commanded.

Up went the Mexican’s arms at full length above his head. Billy had no sooner disarmed him and taken possession of the keys than a Mexican guard, aroused by the hubbub, came in from a rear room, rubbing his eyes drowsily. He, too, was quickly disarmed. Marching jailer and guard before him, Billy hunted out the cell in which Seguar was confined.

“Como le va, amigo?”

“Ola, compadre! It is you.”

Releasing his old side-partner, Billy pushed the two Mexicans into the cell and locked the iron-barred door upon them. Billy and Segura hurried out of the little prison and, both mounted in Billy’s pony, were soon splashing across the Rio Grande. Safe in old Mexico, they made for the ranch of one of Segura’s friends. Here they lay in hiding for a few days, resting up. Then Seguar headed southward and Billy made his way back to Mesilla.

Young Guns: Emilio Estevez as Billy the Kid, Lou Diamond Phillips as Chavez y Chavez. ‘You got three or four good pals, well then, you got yourself a tribe. There ain’t nothin’ stronger than that. We’re your family now, Chavez.’Bound now for the Pecos country to rejoin Jesse Evans and his cowboy friends, Billy set out from Mesilla in company with Tom O’Keefe. While crossing the Guadalupe Mountains, they were attacked by Apaches. During a running battle, the two boys became separated; the main band of the Indians riding hard on the flying traces of O’Keefe, the others pursuing Billy and making the cliffs ring with their war-whoops. When his horse was shot under him, Billy scrambled up a steep hillside, dodging among giant boulders and working gradually toward the crest of the ridge. Dismounting, the Indians charged after him. Billy killed two in their first rush. Sheltering themselves behind rocks and trees, the savages rained bullets about him. As one peeped over a boulder and shifted his gun into position, Billy planted a shot between his eyes. As another was slinking from one ambush to another, Billy dropped him in his tracks. Another, who drew himself over a ledge within twenty feet of Billy, fell with a bullet through his heart and, tumbling down the hill, lodged in the branches of a tree, where he hung suspended. With his score at five, the Indians gave up the fight, and Billy, slipping over the ridge, found safety in flight.

This is the story of his adventure that Billy himself told when, after wandering for three days and subsisting on wild berries, he found his way into Murphy’s cow camp on Seven Rivers and was welcomed by Evans, Morton, Baker, and McDaniels. O’Keefe, it may be added, also escaped the Indians and got back unhurt to Mesilla.

Billy struck the Pecos Valley in the fall of 1877 a few weeks before he was eighteen years old. Staked to a pony by his cowboy friends, he arrived a little later at Frank Coe’s place on the Ruidoso where, as we have seen, he spent most of the following winter, eventually taking employment at Tunstall’s ranch on the Rio Feliz to remain there until the murder of the Englishman (Tunstall) launched the Lincoln County war.

The foregoing tales may be regarded, as you please, as the apocryphal cantos of the saga of Billy the Kid. They are not thoroughly authenticated, though possibly they are, in the main, true. Most of them are perhaps too ugly to have been inventions. If you are skeptical, your doubt may be tempered by the fact that they have at least always gone with the legend and have such authority as long-established currency may confer.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024