The adult world took one look at Brian Jones, or heard one upsetting rumor about him, and they knew that this generation was making demands of life that life was never going to meet, that it would end in catastrophe, and that these musicians would drag down much else, including many young people, with them when the time came.The Lost Boy

Dead now for 43 Julys, Brian Jones, probably because he did not outlive the era of the Stones' greatness, is preserved for our examination in that fantastically combustible mixture of European bohemianism with African-American music that blew English pop music around the globe. Was there a whiff of brimstone about him, or was he simply the wonderful golden-haired child born for otherworldly adventure?

By Christopher Hill

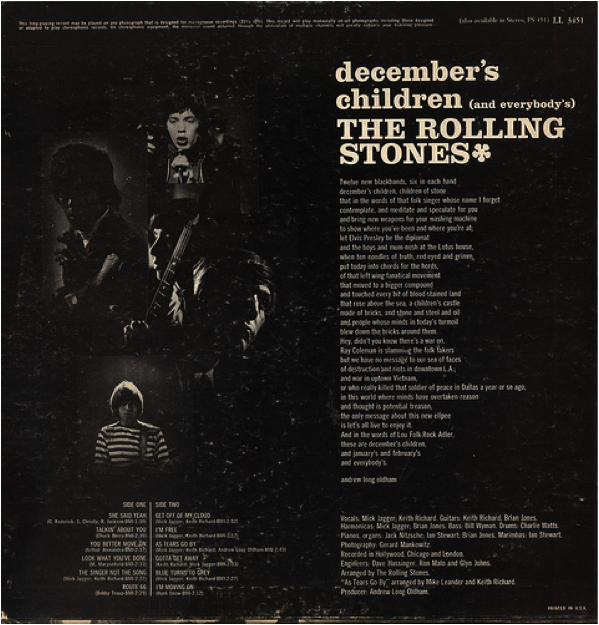

Some years ago I found myself driving from Nashville to Memphis with one of the managers of the great 1980s cow-punk band Jason and the Scorchers, along with an old friend of his from Florida. The friend was an infinitely amiable southern hippy, but one who seemed to have gotten a little lost, as sometimes happens to amiable hippies. He had the rock and roll equivalent of the combat veteran's "thousand yard stare," but with him it took the form of a constant bemused expression, as if he were always living in that instant when you're just getting the joke. I knew he had led a picaresque life. He told me about how he had gotten prescriptions from Elvis's doctor. He had spent some time in London in the ‘60s and I wanted to hear more about it. I asked what took him to the U.K. at the height of Swinging London's great party. In response, he asked me if I owned the Rolling Stones album, December's Children. I said of course.

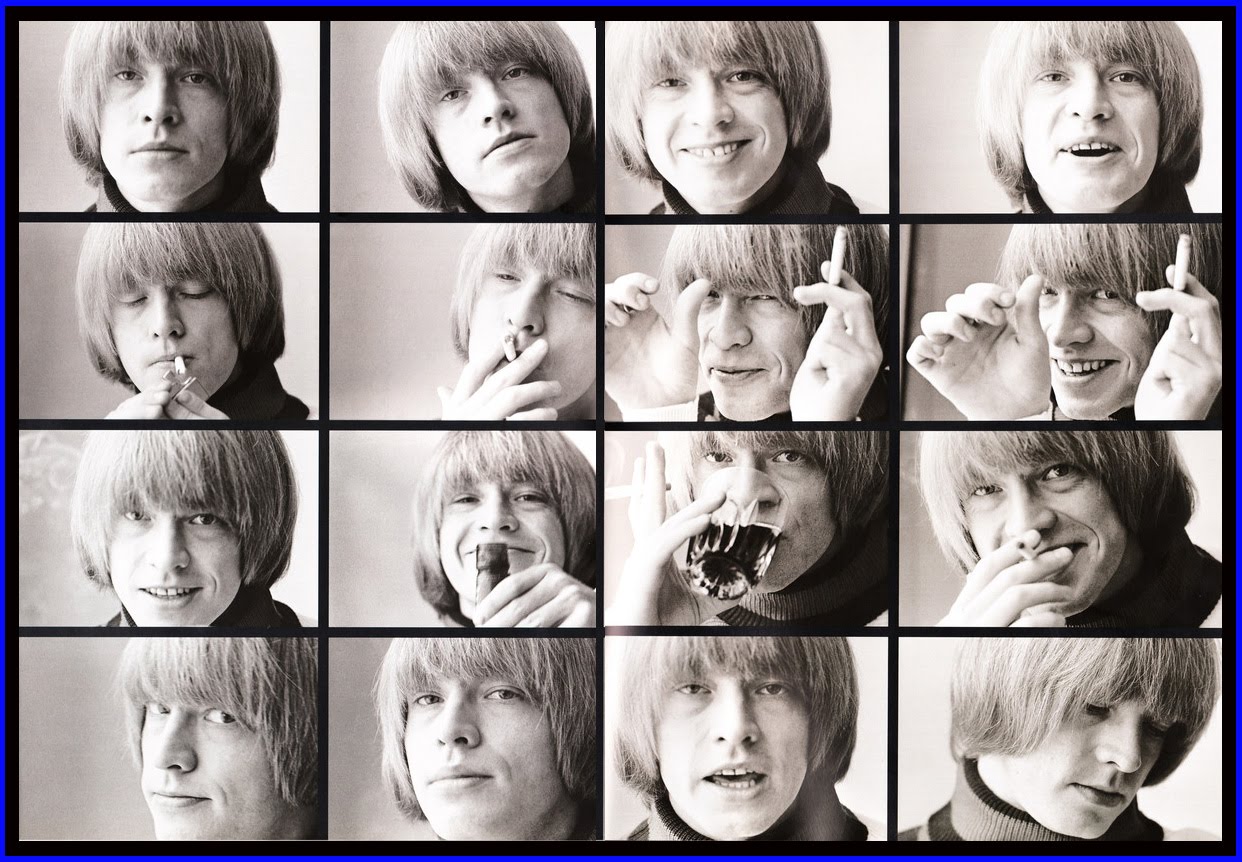

He asked me if I could picture the photo of Brian Jones on the back of the album sleeve. At that moment I knew exactly what he was going to say. Of course I could picture it--a backlit medium shot of Brian wearing a striped jersey, guitar strap over his shoulder, his golden bowl of hair transformed into a corona by the light from behind. For my friend in the car, encountering that picture triggered the classic initiatory rock and roll experience--"I...want ...to be... like... that." And I understood it, because I had studied that picture too. The picture was the coolest thing he'd ever seen, he said, and he knew he had to understand more about it, to see if some of whatever-that-was could be acquired or attained. It called him to search for a different kind of life.

The singular magic and fascination of the Rolling Stones can partly be explained by the fact that they are not one thing but two: the Stones are the music of African America, and they are that music as interpreted by...something else, a very different sensibility. What sensibility? White? European? English? Yes to all those things, but that doesn't quite get it. Parodistic, ironic, bohemian, fantastic, decadent, psychedelic, sophisticated? That's beginning to get it. Whatever you call it, that something else, for many Stones fans, is embodied in the lost and glamorous figure of Brian Jones, dead now for 43 Julys. In Brian Jones, probably because he did not outlive the era of the Stones' greatness, is preserved for our examination in that fantastically combustible mixture of European bohemianism with African-American music that blew English pop music around the globe.

The Rolling Stones, ‘Child of the Moon,’ B side of ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’: ‘…the particular groove and ambience of this music reflects the presence and sensibility of Brian Jones.’There's a whiff of brimstone about Brian Jones. For a band that thrived on giving fans a frisson of glamorous darkness, Brian may have been the only one that actually cultivated his own little patch of evil, like training a febrile monkey he could release at will. When you see him looking really wasted, something leering looks out from his eyes, a slack-mouthed froginess takes over, turning his fine features into lubricious caricature. But just as surely, many people who knew him saw him as the latest avatar of all the lost boys of English children's literature, the wonderful golden-haired child born for otherworldly adventure.

Brian Jones founded the Rolling Stones on May 2, 1962. That was the day he placed an advertisement in Jazz News inviting musicians to audition for a new R&B group at the Bricklayers Arms pub in London. Pianist (and later Stones roadie) Ian "Stu" Stewart was the first to respond. Later Mick Jagger appeared. Next Jagger brought along his childhood acquaintance Keith Richards to rehearsals, and Keith soon joined.

Brian named the band. During a phone call to place an ad for an early club appearance, Brian was asked the name of the band. The band had no name yet--in all the rehearsing they'd never discussed it. Jones glanced around for inspiration and noticed a Muddy Waters LP lying on the floor, of which one of the tracks was "Rollin' Stone." His band, he said, was the Rollin' Stones.

There is a rock and roll aphorism that has perhaps more exceptions than applications, that says band needs one person to live the life, another to sing about it. While Brian was alive, that role was more naturally his than Keith's.There is a rock and roll aphorism that has perhaps more exceptions than applications, that says band needs one person to live the life, another to sing about it. According to this formula, many fans see Keith Richards as leading the quintessential rock and roll life that Mick merely depicts. But while Brian was alive, that role was more naturally his than Keith's. The Stones were seen as young men who lived life on the edge, but Brian's 1960s walk along the precipice was more hair-raising and finally more disastrous than the rest.

In 1968, when director Donald Cammell cast Mick Jagger to play Turner, the reclusive rocker in the movie Performance, he assumed he had a natural to portray an archetypal ‘60s British rock and roll star. He told Jagger just to be himself, but somehow Mick being himself wasn't working; he couldn't translate his own enormous stardom into a characterization. Both men were getting frustrated when something clicked for Mick. "I did Brian," was how he put it. And it was immediately obvious to him and Cammell that he had found the character. People who watch Performance now, with the decadent Turner haunting his Gothic London manse, imagine they're seeing the essential Mick Jagger at his zenith, and the movie has shaped the perception of Jagger for decades. But it's only partly Mick they're seeing. Mostly it's Brian.

Mick Jagger, ‘Memo from Turner,’ from Performance. Trying to find his character, Mick said ‘I did Brian.’There's a certain subset of Rolling Stones fans who remain perversely interested in the Stones' psychedelic period. The prevailing view has long been that this was their least effective phase, an unwise surrender to a trend by guys who should have stayed true to their rhythm and blues origins. But that's to ignore the evidence of your ears. These songs from the middle years of the ‘60s have a particular flavor that has never become dated or kitsch, like so much psychedelia--less dated, honestly, than big chunks of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. Though they never stopped delivering lethal R&B, from the moment the Stones were able to write their own material, it was a mannered, colorful, original and very clever (not to say eccentric) style of R&B. Listen again to "Have You Seen Your Mother Baby (Standing in the Shadows)?" It's an over the top barrage of hyper kinetic noise and symbolist lyrics (with horns!) that could not rock harder, yet from which you might never deduce the existence of Muddy Waters. What Stones fan would want to do without "Lady Jane" or "Ruby Tuesday"? "Paint It Black," "She's a Rainbow," "Child of the Moon" (starting with that excited, unintelligible shouting over rolling power chords), "Dandelion," "We Love You" or even "The Lantern" or "The Citadel" from Satanic Majesties? More than any single Stone, the particular groove and ambience of this music reflects the presence and sensibility of Brian Jones.

The Rolling Stones, ‘Paint It Black,’ Brian Jones on sitar: ‘…It is his mad sitar-plucking that chiefly propels ‘Paint It Black’ so recklessly into the dark.’After their first few albums, as the ‘60s passed their mid-point, the Stones found themselves facing an artistic challenge. For a musician, say, in the Mississippi Delta there was a deep and basic connection between his music and his world that could feed and fuel his art for a lifetime. On the other hand, when it came time for the Stones to graduate from their apprenticeship and start creating original material, there was no obvious affinity between their African-American music and London in the mid-‘60s. Their job would be to invent it, to apply the music to their world and see what would happen.

Brian Jones may have been the most passionate blues scholar of all the Stones. But at this crossroads Brian offered the band the crucial missing link to an English tradition--the long English line of hashish smoking, laudanum-tippling occultist dandies from the 19th century on down, all the beautiful Dorian Greys who were soft-spoken with beautiful manners, about whom the most extravagant and shocking stories were told, a tradition of elegant and outrageous British bohemianism. In America, the blues stood in the margins of society, and so had the room and freedom to critique the center from the outside. Brian provided the bourgeois young men of the Rolling Stones a place in an English counter-tradition, an essential location in the margins from which they could launch their version of rock and roll. For the first time since English sailors started bringing those exotic 45s into the U.K. in the 1950s, there were musicians prepared to answer the question, what would English rock and roll--an oxymoron, a contradiction in terms--sound like? With Brian, the Stones were able to craft a really original iteration of R&B, an unprecedented hybrid that was adventurous, modern and European, but whose heart never stopped beating to the primal strut, of which they had made themselves the greatest living masters.

1966 was the hinge. Mick and Keith were hitting the first of their great peaks as songwriters and, with Brian urging them on and throwing in ideas, the Stones began to acquire the distinctive style that would characterize the first and most creative phase of their career. Brian could hear the sounds that were needed. With his gift for getting something striking out of just about every instrument he ever picked up, he was the Rolling Stone who knew how to realize that style.

In April of that year the Stones released their breakthrough album Aftermath, their first with all original material. On an album notable for its musical experimentation, Brian is the experimenter in chief. He's everywhere, playing a variety of instruments not previously associated with rock and roll--including sitar on "Paint It Black,” dulcimer and harpsichord on "Lady Jane" and "I Am Waiting,” marimbas on "Under My Thumb" and "Out of Time," as well as the usual harmonica, guitar and keyboards.

‘Brian's mellotron turns ‘We Love You,’ a hymn of forgiveness to the Stones' drug-squad nemeses, into a frenzied oriental rite.’ The Rolling Stones, ‘We Love You,’ promo video, featuring a re-enactment of scenes from Oscar Wilde’s trial. Lennon and McCartney are part of the background chorus.Brian knew how to immediately evoke moods and atmospheres with just the right stroke at the right moment. His piano and recorder playing in "Ruby Tuesday," for instance, lifts the song into a sun-dappled place between the past and present where we can feel the presence of the sad and mysterious woman at the song's center. Brian's mellotron turns "We Love You,” a hymn of forgiveness to the Stones' drug-squad nemeses, into a frenzied oriental rite. It is his mad sitar-plucking that chiefly propels "Paint It Black" so recklessly into the dark. It is his sinisterly quiet marimba that makes "Under My Thumb" so wickedly irresistible. Brian's harpsichord in "Lady Jane" creates a cold and glittering setting for Mick's calculating Renaissance seducer.

Patti Smith once said of this era that the Stones were the only rockers who knew how to "bring together the unspoken moment and the hot dance of life." Again and again it's Brian who opens the door to the unspoken moment, the visionary glint in a Stones song. Brian, after all, was the Stone who was said to have seen angels as he emerged from the dark of the London clubs at dawn onto the grey streets.

As far as more conventional rhythm and blues instrumentation goes, Brian provided the stylistic strokes that enabled this group of young Englishman to approach the music from the beginning with a curious authority that set them apart from all the other would-be English bluesmen. Brian was the band's slide guitarist, playing slide on cuts ranging from the early "I Wanna Be Your Man" to 1968's "No Expectations.” And while Mick is usually thought of as the man who adds such inspired harp playing to the classic Stones sound, that was not always the rule. From "Not Fade Away" in 1964 to "Prodigal Son" in 1968, Brian plays some of the most atmospheric harmonica in the Stones' opus. And, of course, for most of this time Brian was also holding down his job as rhythm/second lead guitarist for the band. Keith says that he and Brian developed a technique they called "guitar weaving" from listening to Jimmy Reed albums: "We listened to the teamwork, trying to work out what was going on in those records; how you could play together with two guitars and make it sound like four or five," says Keith. The sound of Jones's and Richards's guitars together became a signature of the early Stones, both guitarists playing rhythm and lead without clear distinctions between the two.

And of course, being a Rolling Stone, Brian was first of all a rocker. What kind of rocker was he? Listen to the vibrato guitar on "Please Go Home." He was completely deadly, in a wonderfully unhinged kind of way.

Brian's last session with the Stones was adding autoharp to Keith's song "You Got the Silver" on Let it Bleed. And so Brian was a presence from their first album to the end-of-the-‘60s triumph of their greatest album.

Oh and by the way, that classic Stones riff that opens "The Last Time"? That's not Keith.

Brian's dark side could get very dark. He posed for a German magazine in an SS uniform with his boot crushing a doll, and indeed he could be arrogant and cruel. He seems to have almost willfully sired a string of illegitimate children across the south of England, generally ignoring them and their mothers subsequently. And he had a habit of beating up his girlfriends. For some, that would be sufficient to close the book on Brian Jones, no matter who he was or what else he did, and it would be hard to argue with them. What would the final judgment be on Brian Jones, weighing his heart on the scales? Salvageable or finally hopeless? On the other side of the scale would be his genuine, almost paternal solicitude for the Stones young fans, with whom he was decorous and gentle. There seem to be few who knew him who were ever ready to completely give up on him. In any case, you can't Photoshop Brian Jones out of the picture without making the picture false. You can't tell the story without him--he'll be there, regardless of whether you ignore him.

During his life, Brian was probably the most visible Rolling Stone. With his golden hair and his outrageous Alice In Wonderland sartorial style, he embodied for bourgeois Britain everything they found most unsettling about the Stones. He knew this, and he bated them. And so he became a target. The British establishment seems to have sensed that here was one Stone they could break if they kept the pressure up, and Brian wasn't ready when they wheeled up the heavy guns. A harassing series of busts, some almost certainly involving planted evidence, a night in Wormwood Scrubs prison, the constant threat of long-term incarceration, pushed him to his limit.

Brian's mental and physical health were always finely balanced. It would be hard to pick a more dangerous path for a physically and psychically fragile Piscean asthmatic than the life of a ‘60s rock and roll superstar. He went through several rounds of residential treatment at mental health facilities, and was twice ordered by the courts to receive psychiatric care. Added to his innate instability, his massive intake of drugs and alcohol finally rendered him useless to the Stones, a once glittering asset turned into a liability. With his legal record, he couldn't get a work permit to participate in the planned 1969 tour of the United States, and so the Stones got a new guitarist, and Brian was finally out.

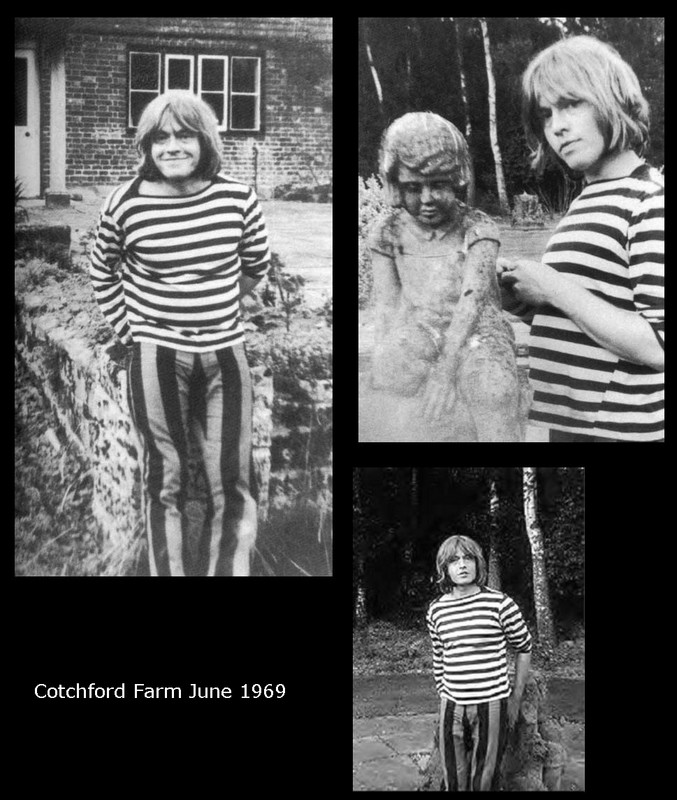

The last known photos of Brian Jones, taken by schoolgirl Helen Spittal on June 23, 1969, at Crotchford Farm, the former country home of Winnie-the-Pooh creator A.A. Milne: This world, too, offered magic--essential for Brian--but unlike his London world, it was a magic rooted in the end in love.To get away from the temptations, cronies and parasites of London--and from the unsleeping eye of the Metropolitan police--Brian bought a house in the country in 1968, a place called Cotchford Farm in East Sussex, about an hour's drive from London. This was not just any house. A.A. Milne, the creator of Winnie-the-Pooh, bought it as a vacation home for his family in 1925. The grounds and the immediately surrounding countryside formed the setting for the exploits of Christopher Robin and Winnie-the-Pooh. The Hundred Acre Wood, the North Pole, the Six Pine Trees, Owl's house, the "enchanted place at the top of the Forest" were all a short walk away in the woods around the house. It was a deeply peaceful environment. Where once Brian had assumed a place in the line of the wicked London rakes, now he stepped into a role in another English tradition which also stretched back to the Victorian Age, the numinous world of childhood as imagined in English children's stories.

A.A. Milne and his son Christopher Robin at Crotchford FarmThis world, too, offered magic--essential for Brian--but unlike his London world, it was a magic rooted in the end in love. Maybe he thought that in a place like Cotchford Farm he could turn again and start over, change from Dorian Grey to Christopher Robin. As Mick Jagger would sing some years later, Brian made a rag pile of his shiny clothes and warmed himself by their burning. He began to get glimpses of how his expulsion from the Stones might free him in certain ways. Though he still drank heavily at times, he apparently stopped using recreational drugs. People who went out to see him after he'd been at Cotchford for a while thought that he looked better than he had in years. That changed appearance accompanied suggestions of a change of heart. "Brian got very nice" after the move to Cotchford, Charlie Watts has said. He played Creedence Clearwater Revival records over and over, hearing in John Fogerty's "swamp-rock" a fresh, imaginatively resonant approach to the music of the American south, his first love. He thought about starting a new band to try something similar.

On the warm night of July 2, 1969, Brian and some friends stayed up late talking and drinking on a bench by the swimming pool behind the house. At about midnight, Brian announced that he was going for a swim. His girlfriend, Anna Wohlin, tried to talk him out of it. Brian had been drinking brandy for some hours on top of his prescription sedation, in addition to still suffering from occasionally severe asthma attacks. Brian told her he'd be alright. He changed into his trunks and dove in. One or two of the others joined him, but before long everyone left the water but Brian. As a group, they went into the house to dry off and change. After a few minutes when Brian didn't appear at the house, Wohlin went back outside to check on him. She found him face down on the bottom of the pool, his golden hair spread out around his head like a corona.

‘What kind of rocker was he? Listen to the vibrato guitar on ‘Please Go Home.’ He was completely deadly, in a wonderfully unhinged kind of way.’Just for an exercise, put a ghostly Brian Jones on stage with the Stones on their 2008 American tour, the highest grossing North American tour by any act, any time. Doesn't work easily, does it? He doesn't really belong. He's from another world, another band. The current Rolling Stones are not traceable directly back to 1962. The origins of the current Stones can be found on Exile On Main Street, Brian's influence gone at last, where the Stones finally constituted themselves as one more (albeit the best) British blues and boogie band who could be counted on to rock you all night long. But the band that Brian Jones founded in 1962 and left in 1968 was a stranger band than the post-‘60s Stones, a more interesting band.

Brian was a living signpost, pointing in the direction of things more interesting and colorful than most people of his day (or our day) assumed was possible. He was not a creature whose existence was very compatible with ordinary life. For Brian to live the normal span of years there were compromises and trade-offs that would have to be made. The adult world took one look at Brian Jones, or heard one upsetting rumor about him, and they knew that this generation was making demands of life that life was never going to meet, that it would end in catastrophe, and that these musicians would drag down much else, including many young people, with them when the time came. For everyone's good, it had to stop. For a while they had hoped to put a Rolling Stone or two in prison for a solid stretch, but it surely occurred to some in the wake of the news from Cotchford Farm that tragedy, however regrettable, might be an even more powerful lesson. It was too late, though, to quiet the kind of tremors that Brian had set going when he placed his ad in Jazz News. They only spread wider and got stronger until they rattled the once-solid frame of the West. We feel the vibration still.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024