Where The Soul Of The People Never Dies

The (R)evolution Continues In Chicago Blues

By David McGee

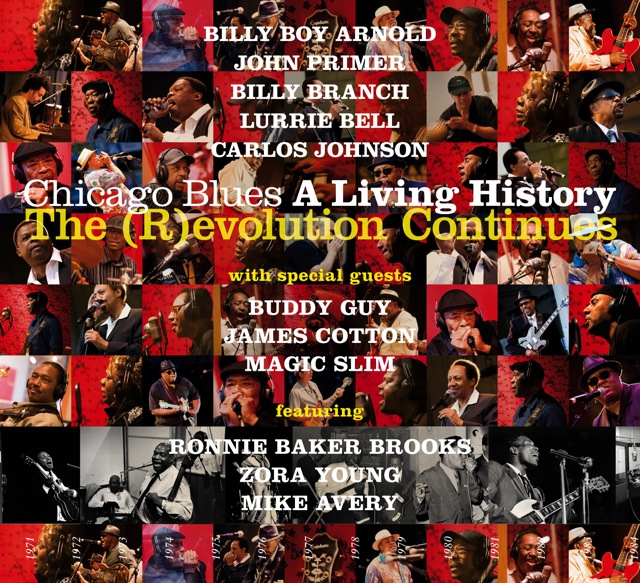

CHICAGO BLUES: A LIVING HISTORY--THE (R)EVOLUTION CONTINUES

Various Artist

Raisin’ MusicIf you love the blues you know there cannot be too much of it, whether it’s in the form of the newest entries or salutes to those who made it great, be they from rural outposts or urban enclaves. Chicago, of course, one of those urban enclaves, holds a revered place in blues history past, present and future, and that history demonstrates how the rural became the urban and was developed into a singular force in American music in the 20th Century. In 2009 Raisin’ Music released a vital 21-track, double-CD home to Chi-town’s blues masters in Chicago Blues: A Living History, and earned a Grammy nomination for its efforts. What worked so beautifully the first time around does so again, with equal power, on Chicago Blues: A Living History--The (R)evolution Continues. Like its predecessor, the new release contains classic songs by several artists who are no longer with us; but check the title again: A Living History. This is about a spirit, a sound, an aesthetic that never dies, and about a couple of generations of younger blues artists who are not only keeping the music vital, but assuring its longevity so that future generations of musicians and fans can keep the flame burning.

John Primer performs Muddy Waters’s 1949 song ‘Canary Bird’ live at WYCE, Grand Rapids, MI, on February 12, 2011. Primer’s version of this tune also appears on Chicago Blues: A Living History--The (R)evolution Continues.As producer Larry Skoller explains in his liner notes, the thrust of this second volume is not only to construct a timeline of 1940s piano-driven blues through the 1950s’ evolution into an electric guitar-and-harmonica driven style, but to go a step further and illustrate how the classic Chicago blues sound evolved into the template for rock ‘n’ roll. As the connective tissue between then and now, a legendary lineup of veteran giants has been enlisted: Buddy Guy, James Cotton, Magic Slim, Zora Young, Ronnie Baker Brooks (Lonnie Brooks’s son, representing the new old guard). But the bulk of the heavy lifting from song to song falls to Billy Boy Arnold, John Primer, Lurrie Bell, harmonica master Billy Branch, the rhythm section of bassist Felton Crews and drummer Kenny Smith; Roosevelt Purifoy and Johnny Iguana on keyboards; guitarist Billy Flynn. What they create over the course of two discs sounds like one of the greatest nights you will ever experience in Chicago blues club--it has a driving, infectious energy about it, a friendly vibe, and a casual feel that comes from virtuosos making what they do sound easy.

Lonnie Johnson’s original 1942 recording of ‘He’s a Jelly Roll Baker” is given a makeover by Billy Boy Arnold and Billy Flynn on Chicago Blues: A Living History--The (R)evolution Continues.The journey on Disc 1 begins I942 with a mellow-down-easy treatment of Lonnie Johnson’s suggestive classic, “He’s a Jelly Roll Baker,” with a wonderfully low-key, wry vocal by Billy Boy Arnold recounting the many occasions when a man’s facility in the art of lovemaking trumps whatever legalistic transgressions he may have committed. Billy Flynn’s tasty single-string guitar has the honor of evoking Lonnie’s presence and Johnny Iguana adds some swinging piano to the mix. The same lineup proceeds through a grinding take on “I’ll Be Up Again Someday,” the 1946 tune by the guitar-and-piano duo Tampa Red and Big Maceo that is a rewrite of the Mississippi Sheiks’ “Sittin’ On Top of the World,” with vocalist Arnold’s matter-of-fact determination articulating the protagonist’s unvanquished spirit. Billy Boy gets to roll out some honking, shimmering harmonica flourishes on Sonny Boy Wiliamson’s accusatory gem from 1941, “She Doesn’t Love Me That Way.” John Primer makes his entrance into the festivities with a powerful, declaiming vocal and stinging, stuttering guitar powering Muddy Waters’s 1949 “Canary Bird” in a dark, spare arrangement featuring only the Crews-Smith rhythm section keeping the sturdy, unrelenting beat going behind Primer. With Matthew Skoller sending up a pinched, trebly harmonica cry, husky-voiced Lurrie Bell becomes the desperate, down-on-his-luck character scraping for his next dollar in Floyd Jones’s dark vision from 1947, the churning, stomping “Stockyard Blues.” James Cotton gets into the action in typically memorable fashion, with some scorching harmonica entreaties in a furiously motorvatin’ take on Jackie Brenston’s Sun classic, “Rocket 88,” Sam Phillips’s choice to be designated the first rock ‘n’ roll record. Chuck Berry doesn’t always show up as a Chicago blues artist, but the fellows at work here respect Berry's blues roots and turn his “Reelin’ and Rockin’” into a stop-time 12-bar fusillade of raucous guitar (Billy Flynn) and spirited vocalizing (Primer) with Johnny Iguana storming across the 88s as if possessed by the spirit of Johnnie Johnson.

Buddy Guy’s 1970 version of ‘The First Time I Met the Blues.” He revisits the song on Chicago Blues: A Living History--The (R)evolution Continues. This clip is from the movie Chicago Blues.Opening Disc 2, Buddy Guy makes his only appearance unforgettable, with a richly textured, deep blue vocal and a breathtaking guitar solo that ranges from howling protest to reflective rumination and back on the churning stunner, “First Time I Met the Blues,” from 1960. There’s no letup from there: Magic Sam comes storming onto the scene with a new take on Chuck Willis’s swinging “Keep a Drivin’,” with Sam holding forth by way of a hearty, assured vocal and multi-textured guitar solo on a track that reunites him with Primer, who backed Sam on rhythm guitar for 13 years. Returning the favor, Mike Avery steps in for a plaintive, pleading vocal on the Magic man's sensuous blues ballad “Easy Baby,” a remarkable, nuanced performance that sensitively explores the emotional shadings of Sam’s lyrics, with Flynn’s reflective guitar punctuations and Iguana’s active right hand on the 88s enhancing the slow boiling intensity of Avory’s reading. Divesting himself of a gritty, smoldering vocal and truly nasty, shimmering harmonica flourishes between verses, Billy Branch brings heat to the foreboding atmosphere he, Flynn, Crews and Smith establish in scorching the Junior Wells arrangement of Elmore James’s 1966 gem, “Yonder Wall." In an all-too-timely message from 1980, Zora Young sings it like she means it in belting out Sunnyland Slim’s cautionary but fiery entreaty, “Be Careful How You Vote,” a reality check for those who have found themselves bamboozled by double talking politicians--when she moans, “Aww, the one you vote for, he might just let us down,” you can’t help but turn your thoughts to the current occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. Fenton Robinson added some jazz spice in giving his blues a fuller, more exotic dimension than the traditional Chicago template suggested; his approach is effectively realized on “Somebody Loan Me a Dime,” a 1967 Robinson tune that here features Roosevelt Purifoy going into some different harmonic places than the usual blues pianist ventures, with Flynn injecting some jazz chordings into his otherwise-tart blues guitar discourse, and Carlos Johnson singing with such suave coolness and jazzy phrasing that his unruffled demeanor almost undercuts the abject loneliness fueling his lyric pleas. Fittingly, it falls to Ronnie Baker Brooks, on the album’s penultimate statement, his own “Make These Blues Survive,” to sound an impassioned clarion call for supporting the blues for future generations--noting in one lyric, “when I play my blues on the north side/everybody wants to report it/when I play my blues on the south side/my people won’t support it”--a disturbing state of affairs he affirms with a white-hot, howling, spitting guitar solo over the band’s funky workout behind him. Practically everyone of note that Brooks learned from is name-checked in the song and that amounts to a blues hall of fame of legendary practitioners, and he doesn’t leave out the younger players who joined him on this project. In the end, the best evidence for the blues’s vitality might well be his own scorched earth guitar solo near the close of the seven-minutes-plus track--after which Brooks’s impassioned concerns seem a bit overstated, because he supplies all the evidence necessary to prove his music’s relevance in our time. As the title says, the (r)evolution continues. More to the point, there’s no end in sight, as long as people are out there in the real world, looking for love in all the wrong places, scrapping to make ends meet financially and trying to stay whole spiritually. In this music the soul of the people never dies.

Chicago Blues: A Living History--The (R)evolution Continues is available at www.amazon.com

Where to go in Chicago to hear the best blues in town or to find information on the latest and greatest in Chicago blues? Visit our buddy Linda Cain’s essential Chicago Blues Guide site. Ms. Cain, an occasional contributor to TheBluegrassSpecial.com, has worked tirelessly to make the Guide the go-to resource for all things Chicago blues--from a going-out guide to reviews and interviews, along with the latest news from the blues scene, plus a directory of Chicago area blues labels and blues radio shows. Support her efforts by paying a visit to the Guide.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024