When History Called, The Big Man Answered

Clarence Clemons In Perspective

By David McGee

As an earlyFather’s Day present, my oldest son, Travis, treated me to the Ultimate Doo-Wop Show at the Beacon Theater on Manhattan’s upper west side on Saturday night, June 18. This is the circle of life: when he was a mere lad, I had taken him to a couple of doo-wop revues at the Beacon and thus introduced him at a young age to some of the great singers in rock ‘n’ roll history. Another night of doo-wop at the Beacon was a wonderful revisiting of treasured memories.

The night turned bittersweet afterwords, when I returned home to the news that Clarence Clemons, the mythical Big Man of the E Street Band, had perished from complications of a stroke he suffered the previous Sunday at his home in Singer Island, FL. Ironically, at about the same time 69-year-old Clarence was taking his last breath in a hospital in Palm Beach, FL, the Ultimate Doo Wop Show’s saxophonist was opening the show by blowing a ferocious take on the Viscounts’ 1959 smash instrumental hit “Harlem Nocturne.” As word of Clemons’s death spread, the outpouring of emotion from fans and fellow musicians all over the world was instant, impassioned, and deserved. Indicative of the deep impact Clemons had made, New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, a professed Springsteen supporter who said the news of Clemons’s death had signaled to him that “the days of my youth are over” (only Clemons’s death, it seemed, could give him pause in the midst of his union busting exercises), ordered all flags lowered to half-staff on June 22 to commemorate Clemons’s passing (an uproar of protest immediately ensued when angry New Jerseyans took to the airwaves and the Internet to question the propriety of ordering flags to be lowered for a musician when a New Jersey soldier, Army infantryman Sgt. James Harvey II, who had been killed in action in Afghanistan, did not receive the same honor. The Gov.’s office responded by explaining that the half-staffing order for Clemons had been issued before word of Sgt. Harvey’s death had been reported, and that the same honor would be accorded the fallen GI on June 24).

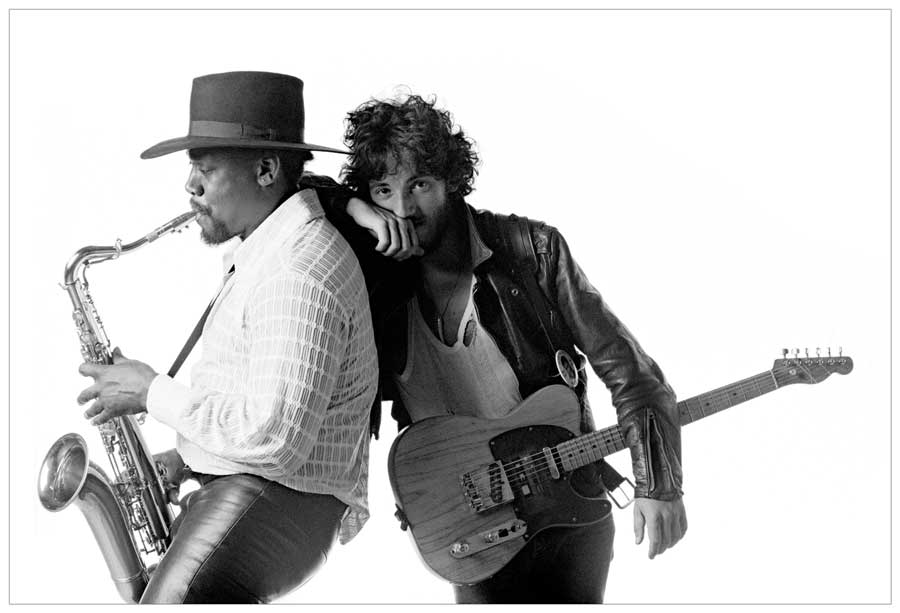

In the days following the announcement of Clemons’s death, the music press was aflutter with all sorts of theorizing about the larger meaning of the Big Man’s presence in an otherwise-all-white rock ‘n’ roll band. Though well meaning, this particular playing of the race card did a disservice to Clemons and Springsteen both (hardly anyone failed to reference the iconic Born To Run album cover showing Bruce leaning contentedly on Clemons’s shoulder as bespeaking a statement of racial unity). Everywhere you looked some music writer somewhere was rhapsodizing over Clemons’s natural fit with a bunch of scruffy rock ‘n’ rollers and, in turn, their embrace of him as one of their own. Some noted the oddity of a black musician in a rock ‘n’ roll band, as if it were a revelation, despite Clarence himself saying, to countless interviewers and in his autobiography (which, granted, was semi-fictional) that being the grandson of a Southern Baptist minister had not confused him in the least about his identity as a musician: “I was always a rock ‘n’ roller,” he boasted.

Questions of Clarence’s ‘originality’ are irrelevant; his understanding of rock ‘n’ roll’s fundamentals and how to execute them was critical to the band’s musical ethos, as much as his showmanship was critical to defining Springsteen’s onstage persona.The disservice to Clemons in this line of thinking goes to the essence of his legacy: Clarence carried with him the weight not of race but of his instrument’s storied place in rock ‘n’ roll history. Clarence knew this history, respected it, and extended it in grand fashion. In a wimpy tribute in The New Yorker, editor David Remnick--wonderful on Russia, not so good on music--took a slight dig at Clemons, writing that he “was not an entirely original player,” and qualifying that with “he was a vessel of many great soul, gospel and R&B players who came before him,” before saluting him as “an entirely sublime band member…” By this standard, as musicians will tell you, no one is “an entirely original player.” But Clarence took what had been handed down, injected his own outsized personality into it while remaining true to Bruce’s vision, and produced something instantly identifiable as his sound within the band context. Questions of Clarence’s “originality” are irrelevant; his understanding of rock ‘n’ roll’s fundamentals and how to execute them was essential to the E Street Band's musical ethos, as much as his showmanship was critical to Springsteen defining his onstage persona. Being a vessel of history, when Clarence Clemons played he distilled nearly three decades of a certain strain of saxophone style into something uniquely his, so much so that succeeding generations of rock 'n' roll sax players are going to be judged by his standard, as he was judged in accordance with the standards set by those whose instrumental voices he shaped into his own.

Illinois Jacquet and Lionel Hampton discuss Jacquet’s early career with the Hampton band. Includes a live performance of the 1942 classic, ‘Flying Home,’ that presaged the development of R&B and was a template for many early rock ‘n’ roll sax players, plus comments from Dizzy Gillespie. From the documentary, Texas Tenor: The Illinois Jacquet Story.The place Clarence came from musically is pretty narrowly focused in terms of players whose style, showmanship and prominence was such that he can be heard in them in a way he isn’t heard in Coltrane, Bird and Prez. From the era immediately preceding rock ‘n’ roll three big honkers set the stage: Illinois Jacquet, one of the great Texas tenors whose solo on Lionel Hampton’s 1942 recording of “Flying Home” presaged the development of R&B and was a template for many of the early rock ‘n’ roll sax players; Sam Butera, the wild-eyed show stopper on tenor whose fame rests equally on his ebullient personality and his contributions to the rhythmic drive of the big band led by Louis Prima and Keely Smith; and Big Jay McNeely, a powerhouse whose prime years spanned the late ‘40s into the early ‘60s after he broke in with Johnny Otis (distinguishing himself on 1948’s “Barrel House Stomp”) before splitting to lead his own band as a productive solo artist on several independent labels in the ‘50s (he had a chart topping R&B instrumental, “The Deacon’s Hop,” in 1949 and a #2 R&B hit--and #43 pop--in 1957 with “There Is Something On Your Mind,” featuring Little Sonny Warner on lead vocal). Nicknamed King of the Honking Tenor Sax, McNeely would often get so carried away in his solos that he would wind up rolling around on the stage in a kind of religious frenzy.

Big Jay McNeely’s ‘There is Something On Your Mind,’ his 1957 crossover pop/R&B hit featuring vocalist Little Sonny WarnerThe playing styles and stagecraft of Jacquet, Butera and McNeely show up in some measure in all of the rock ‘n’ roll sax men from which Clemons ultimately sprang. The sax giant Clemons has been forever compared to is King Curtis, specifically for the work Curtis did on Coasters hits from the late ‘50s into the early ‘60s, as incendiary on the fast tunes as it was sensitive and soothing on the rare subdued number, such as “Shoppin’ for Clothes” (which was also the rare Coasters tune not written by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller), the better to underscore the humiliation of a department store customer--clearly a poor black man--trying, but failing, to buy a suit on credit; but King Curtis himself was building on the style and personality of Gil Bernal, whose dynamic soloing--remarkable and distinctive--on early Coasters hits such as “Searchin’” (1957), “Down In Mexico” (1956) and “Young Blood” (1957), among other cuts, had established a larger role for his instrument as a complementary character to those played by the group’s outstanding comic vocalists Bobby Nunn and Carl Gardner in the vivid “playlets” written for them by Leiber and Stoller. Bernal is the unsung hero in Clarence Clemons’s musical lineage. In fact, Bernal’s hesitating solo on the Coasters’ first Atco single, “Smokey Joe’s Café” (which the group had earlier recorded, unsuccessfully, as the Robins for Leiber and Stoller’s Spark label) is the restrained model for the stuttering sax solos King Curtis perfected on later Coasters singles and which informed Clemons's approach--but the voice of Gil Bernal is in there, too, whispering but ever-present.

The Coasters, ‘Smokey Joe’s Café,’ an Atco reissue of the tune the group had recorded unsuccessfully as the Robins for Leiber and Stoller’s Spark label. Gil Bernal, tenor sax solo; Barney Kesell, guitar.Bernal and King Curtis had competition, though, in the form of Rudy Pompilli of Bill Haley and His Comets. In fact, Pompilli really is the model for Clarence Clemons in being a full-fledged member of a popular, hard working, incessantly touring band that put on a raucous show in which he played second banana as a showman only to Bill Haley himself--Pompilli’s classic pose was flat on his back, blowing a mean sax line, a bit he picked up from his predecessor in the Comets, Joey Ambrose, who had co-opted it from Big Jay McNeely. Pompilli even had his own showcase number, “Rudy’s Rock,” in the 1956 jukebox musical Rock Around the Clock; in the E Street Band, Clemons had a similar showcase moment with the joyous, surf-influenced instrumental “Paradise By the C,” which was sometimes used to open the second half of Springsteen’s epic concerts in the Darkness-River years. (In addition to being in-demand session men, both Bernal and Curtis were solo artists in their in own right but never big stars as such; much he same could be said of Clemons's solo career. Bernal, who joined Lionel Hampton’s band as an 18-year-old, well ahead of his Coasters dates, still leads his own L.A.-based jazz group, by the by.)

‘Let’s rock and roll with a real swingin’ little tune called ‘Rudy’s Rock’: Bill Haley and His Comets in Rock Around the Clock, performing ‘Rudy’s Rock,’ the showcase number for tenor great Rudy PompilliThe Viscounts’ Harry Haller, whose smoldering, sensual sax made the group’s 1966 version of the oft-recorded “Harlem Nocturne” a certified rock ‘n’ roll instrumental classic (among the many artists that had taken a run at it were Duke Ellington, Bill Haley and His Comets, King Curtis and Earl Bostic--“Earl Bostic! Now you’re talkin’!” Clarence once said to me when we were discussing sax players after a show), in essence fashioned the template that Clemons built into the monumental structure teeming with power, passion and pain on “Jungleland.” (How interesting it would have been to listen in on the hours upon hours Clemons and Springsteen spent on the architecture of the Big Man’s part on “Jungleland.”) For sheer signature sound with personality and technique both to recommend it, Steve Douglas ranks with the Mount Rushmore-level rock ‘n’ roll sax players. Based in Los Angeles, he was part of the legendary Wrecking Crew that helped Phil Spector and Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys secure their legends. He played with Elvis, with Aretha, with Bob Dylan, with the Ramones, with Duane Eddy, he made a striking contribution to Willy DeVille’s classic Le Chat Bleu--somehow he even survived Sammy Hagar.

The Viscounts, ‘Harlem Nocturne,’ featuring Harry Haller on tenor sax and Bobby Spievak on guitar. The template for Clarence Clemons’s epic ‘Jungleland’ solo?This is Clemons's musical bloodline. When he became an E Street Band member in late October, 1972, he knew what his predecessors had done, he respected their art and proceeded to put his imprint on it. He never forgot them, nor should we. With Springsteen, he did something none of the others cited here had done before by staying in the spotlight, powers undiminished, for nearly four decades. In Springsteen he found not only a musical kindred spirit (“he was what I'd been searching for,” Clarence once recalled of their first meeting on a legendarily stormy night in 1971. “In one way he was just scrawny little kid. But he was a visionary. He wanted to follow his dream. So from then on I was part of history.”) but also a partner, a friend, with whom he shared a larger vision of where the music could go.

As for the E Street Band’s multi-racial lineup, that was hardly new. The racially integrated Del-Vikings had a mammoth year in 1957 with a million selling single “Come Go With Me,” and were regularly featured in the teen magazines of their era. In 1961 the Marcels, another multi-racial group harmony outfit (boasting one of the finest lead singers in the field in Cornelius Harp) entered rock ‘n’ roll lore permanently with the hits “Blue Moon” and “Heartaches.” How about The Equals? A multi-racial quintet with members hailing from Jamaica, Guyana and London, with Eddy Grant on guitar, they were consistently in the UK Top 50 in the late ‘60s, but U.S. success proved elusive, save for their infectious 1968 hit, “Baby Come Back,” one of the great ‘60s singles. And if memory serves, Santana, the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Sly & the Family Stone, and Janis Joplin’s Kozmic Blues Band all boasted multi-racial lineups and were quite popular. Moreover, as Peter Guralnick documented in his book Sweet Soul Music, the entire history of southern soul is a black-and-white story. Truly, the constant remarking upon the presence of a black man in a white rock 'n' roll band got downright bizarre, as if none of this history had ever happened.

Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, ‘Jungleland,’ the Capitol Theater, Passaic, NJ, September 19, 1978Owing to these examples preceding them, Springsteen and the E Street Band did not represent “an ideal” for me as it did for, say, the New York Times’s Timothy Egan. From its earliest days, rock ‘n’ roll itself--not any one band or artist, but the music--represented the ideal, a place where artists of all colors were welcome, where the message of racial unity was implicit in the integrated radio playlists and visible on the silver screen in ‘50s rock ‘n’ roll musicals, which, however simplistic their plots and wooden their acting, nevertheless portrayed a congenial, comradely relationship between blacks and whites that for me, as a child in the south, made the racist epithets and visible symbols and displays of racism in the real world at first frightening, then puzzling and ultimately repugnant. By the time I saw Clarence Clemons in the E Street Band, his presence signaled a continuing affirmation of rock ‘n’ roll’s promise rather than a groundbreaking event. In the end the songs, the music, the intensity and the energy of a Springsteen show are so overwhelming that to focus on Clemons as the lone black man in the lineup is, first of all, ridiculous, and second, to be blind to Springsteen's concerts being the ultimate pluralistic spectacle, with Bruce's original songs revealing the rich, deep influence black music has had on him, and his encores featuring the Isley Brothers’ “Twist and Shout” and Eddie Floyd’s “Raise Your Hand,” with Clarence’s sax summoning the spirits of all the greats--black and white--that made him possible. Is it any wonder the two of them once exchanged a fleeting but much remarked upon kiss on the lips during a frenzied concert sequence? Really, get over it.

Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, ‘Rosalita,’ live 1984Ultimately, in Clarence’s passing, we--rock ‘n’ roll’s fans, practitioners and chroniclers--have lost a friend who embodied the music’s promise, and more. He was friend to all who loved the life affirming vibe emanating from his benevolent presence, his boundless high spirits and generous soul, but more important, a friend to Bruce of some 40 years’ standing. Bad enough that Phantom Dan Federici is gone; Bruce having to consider Clarence being absent from the stage is painful to contemplate. Industry wingnut Bob Lefsetz thinks the E Street Band is finished without Clemons. This thinking, too, does a disservice to Bruce.

‘In this corner, at 260 pounds, the master of disaster, emperor of the world, king of the universe, Mayor of half of Bayonne, the Big Man, Clarence Clemons!’ ‘Paradise by The C,’ live 1978Consider a statement Bruce issued after Clarence’s death: “…with Clarence at my side,” Bruce wrote, “my band and I were able to tell a story far deeper than those simply contained in our music. His life, his memory, and his love will live on in that story and in our band.”

I know that story; it’s been part of my life since I was six years old. When considering a Clarence-less Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band, I don’t envision any of those musicians quietly receding into history. Instead, I hear a summons, I hear Bruce channeling Elvis channeling Roy Brown and wailing:

“Have you heard the news? There’s good rockin’ tonight!”

Believe it. Keep the faith.

Bruce Springsteen & the E Street Band, ‘Good Rockin’ Tonight,’ Capitol Theater, Passaic, NJ, September 20, 1978

***

The Tenor Of His Times

Carl Gardner of The Coasters Is Dead at 83

By David McGee

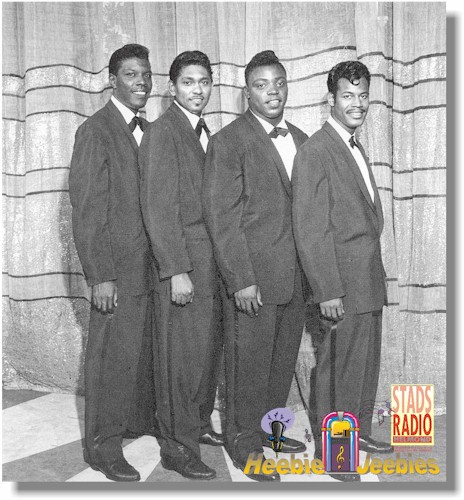

Less noted than Clarence Clemons’s passing was the death four days earlier, on June 14, of the Coasters’ last surviving original member, Carl Gardner, one of the ‘50s classic lead tenor vocalists, of congestive heart failure (he also had Alzheimer’s disease) in Port St. Lucie, FL. He was 83. Teaming with Billy Guy, Leon Hughes and Bobby Nunn, Gardner brought a new sound to group harmony in the witty, often socially conscious mini-dramas custom-written for the group in its first incarnation as the Robins and in reconstituted form as the Coasters by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, who also produced the Robins’/Coasters’ recordings.

The Coasters, ‘Along Came Jones’Born in Tyler, TX, on April 29, 1928, Carl Edward Gardner was raised by a father, Robert, who by day was a hotel bellman and by night a bootlegger; his mother, Rebecca, was a full-blooded Cherokee Indian whose lovely singing voice Gardner credited as the source of his own singing gift, which he was using to make money performing at parties in Tyler before he left for California to pursue a career in music. In 1954 he joined the Robins, a group that had started out with the Johnny Otis Show and had recorded for a number of west coast labels without much success as it struggled to find a distinctive sound. One of their early recordings was “That’s What the Good Book Says,” by Leiber and Stoller, who were then struggling songwriters based in Los Angeles, where they had moved to from the east coast (Leiber was born in Baltimore, Stoller in New York City) in 1950. With $35,000 seed money from Stoller’s father and from a friend of music industry veteran Lester Sill, the duo formed a record company, a publishing company and a distribution company. Among the first signings to the label, Spark Records, was the Robins, but Leiber and Stoller found the lead singer’s voice too unthreatening to deliver the duo’s new song about a prison uprising, “Riot in Cell Block #9,” and so enlisted as an anonymous lead one Richard Barrett, better known now as the man who wrote “Louie Louie.” The implied racism fueling the prisoners’ revolt in “Riot in Cell Block #9” was more pronounced in another Robins single, “Framed,” about an unfortunate black man thrown to the mercy of a Jim Crow judge. The Robins’ Spark singles--which also included the first version of “Smokey Joe’s Café”--did well on the west coast but nowhere else, selling around 90,000 copies. With Spark struggling financially, Leiber and Lester Sill jumped at an offer from Atlantic Records in New York to buy up all the Spark masters and contract Leiber and Stoller to continue working with the Robins while allowing them to produce acts on other labels, making the duo the first independent producers in the music business.

The Coasters, ‘Searchin’’Reissued on Atlantic subsidiary Atco, “Smokey Joe’s Café” sold 250,000 copies, thanks to Atlantic’s nationwide distribution and promotion clout. But the Atlantic deal drove a wedge between the Robins' personnel: two opted to stay with their manager when he started his own label and took the group name with him, leaving Gardner and bass singer Bobby Nunn under contract to Atlantic but without a name or any other vocal support. Ever resourceful, Leiber and Stoller found a masterful comedy singer in Billy Guy and another tenor in Leon Hughes and teamed them with Gardner and Nunn as the Coasters (in honor of the group members’ West Coast roots). As the Robins faded quickly from sight, the Coasters became dominant. Between 1957 and 1961, recording almost exclusively Leiber and Stoller tunes, they defined a new strain of rock ‘n’ roll that mated comedy, topicality and theater in a group harmony format. “Young Blood”/”Searchin’” was Atlantic’s first Top 10 hit during the summer of 1957; nearly a year later, “Yakety Yak,” with its stuttering King Curtis sax solo, became the company’s first chart topper.

Then the Coasters hit a bump in the road, with “Idol With the Golden Head” barely making a chart dent, and “Sweet Georgia Brown” and “Gee Golly” failing to make the Hot 100 chart at all. As Charlie Gillett observed in his essential history of Atlantic Records, Making Tracks, “the problem was to make the meticulously contrived records sound spontaneous.”

The Coasters, ‘Charlie Brown’As Jerry Leiber explained to Gillett: “We spent many hours in the studios with the Coasters, overdubbing their performances because with their material it was critical that the timing, the jokes fall right. Which is another type of recording, really; it’s a lot more plastic, a lot more clinical than going for a great soul performance on a Ray Charles record, or those records with Joe Turner or Ruth Brown, which were usually third or fourth or fifth take: there were no twenty-six takes, or thirty-one takes, or six hours of overdubbing two bars of music, like we did with the Coasters.”

Stoller explained the particulars of getting a Coasters record right: “We would do things like cutting esses off words, sticking the tape back together so you didn’t notice. And sometimes if the first refrain on a take was good and the second one lousy, we’d tape another recording of the first one and stick it in the place of the second one. Before multitrack recording, this was.”

The Coasters’ classic lineup: (from left) Leon Hughes, Carl Gardner, Bobby Nunn, Billy GuyWorking primarily with engineers Tom Dowd and Abe “Bunny” Robyn, Leiber and Stoller perfected their craft on Coasters recordings, as the ensuing records proved: “The Shadow Knows,” the followup to “Yakety Yak,” didn’t do much, but then the floodgates opened: “Charlie Brown,” “Along Came Jones,” “Poison Ivy”/“I’m a Hog For You Baby,” “What About Us,” “Besame Mucho,” “Wake Me, Shake Me,” “Shoppin’ For Clothes,” “Wait a Minute” and “Little Egypt” rolled up the charts. The Coasters brought a new style to the group harmony world, forsaking the smooth, crooning style of legendary groups such as the Ravens or even the harder, gospel-rooted harmony of another Atlantic group, the Clovers. Drawing on his knowledge of jazz, Stoller wrote out the harmonies with an ear towards each singer’s strength and vocal timbre and created, in essence, a new vocal group sound for the rock ‘n’ roll era. With Billy Guy possessed of what Jerry Leiber called “a marvelous sense of timing, and the dirtiest, the most lascivious voice,” the songwriting duo kept on pushing the boundaries of song propriety in the Eisenhower era: “Poison Ivy” and “Love Potion #9” plumbed an unambiguous attraction to and fear of sex (the latter posited a magic elixir as a cure for impotence); “Charlie Brown” made a hero of a class clown in a way no teacher would have approved of; “Smokey Joe’s Café” addressed black-on-black crime long before it became a cultural/political issue; “Framed” was an amusing but biting tale of racist police and courts bamboozling its hapless protagonist; “Yakety Yak” chronicled parents’ fruitless efforts at getting a teenager to behave; “Along Came Jones” was a sendup of old Hollywood’s melodamas in which good and evil were clearly delineated. The Coasters’ first single actually recorded under the Atlantic contract, 1956’s “Down In Mexico,” had a slight Latin feel and a storyline informed by the its writers' immersion in L.A.’s Mexican-American culture.

The Coasters, ‘Down in Mexico,’ 1956, the first single the group recorded under its contract with AtlanticAfter the Coasters’ run of hits ceased in the ‘60s, Gardner tried to keep the group together to work the oldies circuit, only to find that there were several groups billing themselves as Coasters, fronted by former or part-time Coasters. Holding the legal rights to the group name, though, Gardner insured that fans knew the difference between the real thing and a shabby knockoff. In the early ‘90s he was diagnosed with throat cancer (he was a lifelong smoker), recovered but effectively lost the suppleness in his tenor. He gave up singing lead in the Coasters and turned the job over to his son, Carl Jr., while remaining involved as a coach to incoming singers. To the end, and contrary to his own assertions, he remained bitter over money he claimed he and the other Coasters were due in their heyday but were never paid, explaining, “You must remember in that era you didn’t sue a white man, you didn’t do that.”

Yet in his unauthorized biography posted online, he writes:

“I've tangled with the mob, broken the color barrier in Las Vegas, cursed out racist audiences who had come to hear "race music,’ and at times carried a gun on stage. At times I got run off of stage, and right out of town. But yet and still I managed to sell over thirty million records on the National Record Charts, in my time. My group has often been ripped off by many claiming to be me, using my name with their voice and cashing my check. I steeled myself and stood up to it all. The glamour, the danger, the glory and the bullshit. In my weakest moment I still marched on.

“Through all the ups and downs of a joyous and yet painful career, I have come out unlike many others. Still performing, still standing, still sane, and intact. The goal was to be rich and famous. And I became both, for a while. But in the end I have ended up coasting on the fame, and trying to see just who had gotten rich.

“Now I know why I'm sitting here in my office in the wee hours of the morning staring down the dawn. I know what I'm missing. I know what I earned, I know what was promised, and I realize now with some bitterness what little I got. Granted it's comfortable and not the nightmare and losing battle that many other artists of my time have endured, but it is not what was promised.

“I'm a long way from my hometown of Tyler, Texas. Although I didn't put Tyler, Texas on the map, the way the Branch Davidians put Waco, Texas on the map, that was never my original intention. All I ever wanted to do was sing, what I actually did was much more.

“I never dreamed that so many problems and dangers came with being a star. And so little money, even though I've sold millions and millions of records. My story is wonderful given the circumstances, yet shocking given the outcome. Thank God, I've moved past the bitterness and anger that for years plagued me. With only faith and sheer determination I was able to overcome all of the horror, and begin to write about it.”

The Coasters, ‘Yakety-Yak’In his Speakeasy blog published in the Wall Street Journal of June 14, Charles Passy, who interviewed Gardner in 1996 when he was covering pop music for the Palm Beach Post, recalled Gardner being “strangely at peace with his near-anonymous suburban existence. (I say ‘near’ because it was kind of hard to ignore the Cadillac in the driveway with the license plate that read, ‘Yakety Yak.’) Like so many ex-New Yorkers, Gardner had come to Florida to escape the cold weather. Now, with his loving and attentive wife, Veta, he was building a new life for himself. Traces of bitterness remained. ‘You’re looking at a millionaire that don’t have it. That hurts,’ he told me for the profile I eventually wrote. But so did a kind of goofball worldview that afforded him a little perspective. When I asked him what he wanted in life, he had an immediate answer: $10 million. Not for himself, he insisted, but to help others. Then, with a knowing smile, he paused and added, ‘As long as I keep me $3 million.’”

Carl Gardner’s first marriage ended in divorce. In addition to his wife, the former Vera Ryfkogel, whom he married in 1987, his survivors include a brother, Howard, of Los Angeles; a sister, Carol Bartlett, of East Orange, NJ; sons Carl Jr., of Dallas, TX, and Ahilee, of Pennsylvania; a daughter, Brenda, of Dallas; three stepsons, Hanif, Raymon and Wayne Lalloo, all of Port St. Lucie; and several grandchildren and step-grandchildren. The Coasters were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1987. In June 2007 Gardner's autobiography, Carl Gardner: Yakety Yak I Fought Back--My Life with The Coasters, was published by AuthorHouse.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024