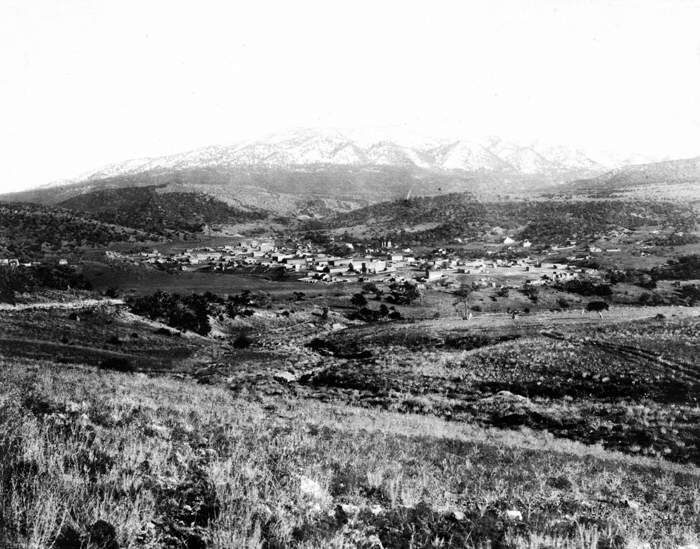

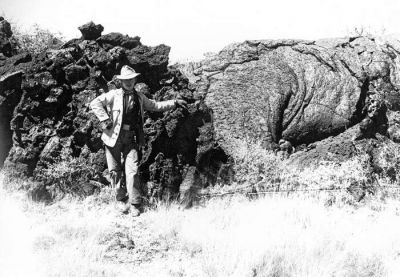

‘The peace of morning lay on White Oaks. The little bowl of a valley was a chalice brimming over with the crystal wine of the sunlight. The green grass on the slopes was like the velvet map of a rug on which piñon copses formed dark arabesques.’ The town as it looked in 1905, 34 years after Sheriff Pat Garrett visited to pick up lumber to use in the gallows to be built for Billy the Kid’s execution. It was here in White Oaks where Garrett heard of the Kid’s murder of two deputies and escape from Lincoln Country jail. He dashed back to Lincoln to begin the manhunt that would end on a starry night in Fort Sumner with Garrett felling the Kid with a single shot in the moonlit shadows of Pete Maxell’s house.The Rendezvous With Fate

The peace of morning lay on White Oaks. The little bowl of a valley was a chalice brimming over with the crystal wine of the sunlight. The green grass on the slopes was like the velvet map of a rug on which piñon copses formed dark arabesques. Against the turquoise of the April sky the mountains stood with etching-like distinctness.

“I’ve been busy for the past two months gathering evidence against Pat Coughlin,” John W. Poe was saying to Sheriff Garrett, as the two men stood on the edge of the sidewalk in front of the Long Branch saloon. “Billy the Kid with his stolen cattle has made the King of Tularosa rich. I just got back from Tombstone. I found that steers from the last herd the Kid stile on the Canadian River had been sold by Coughlin as far to the southwest as that. I’ve found a lot of hides with Canadian River brands on them hanging out to dry around Fort Stanton. These also were cattle the Kid had stolen and Coughlin had sold. I’ll be ready to lay my evidence before the grand jury as soon as--“

There was a sudden whirr of excitement among the loungers on the street. A Mexican horseman was seen riding toward town out of a tumult of dust on the Carrizozo road. He dipped out of sight in the deep arroyo of the creek, came racing into view again, and, rounding into the main street, halted abruptly beside the two officers, his pony marbled with sweat and foam.

“El Chivato!” he announced excitedly, “asesinó a sus dos guardias en Lincoln y se escapó a las sierras. Cogió la pistola de Bell mientras jugaban a monte y tiró una bala dejándole muerto. Luego mató a Ollinger con su propria escopeta cuando éste corrrió a través de la calle. Después montó a caballlo y huyó del pueblo hacia el poniente. Nadie sabe donde se encuentra ahora.”

Which conveyed succinctly the news of the tragedy in Lincoln and the escape of Billy the Kid.

Garrett stared at Poe and Poe stared at Garrett. For an interval neither uttered a word. The news struck them like a blow between the eyes.

“Ain’t that hell?” said Garrett at length. “I told those fellows to watch the Kid. They must have got careless. Now they’re dead and the Kid’s gone. That means I’ve got to do it all over again. Now I’ve got to kill the Kid or get killed trying. He won’t be taken alive again. Well, no use crying over spilt milk. I’ll saddle up and strike back for Lincoln.”

A few minutes later, Sheriff Garrett went galloping out of town. Out of the mountains about White Oaks, across the Carrizozo plains, up the steep hairpin curves of Nogal Hill, along the edges of dizzy precipices with a thousand-feet drop beneath him, and then on the long down-grade beyond, he travelled under whip and spur, driving his pony to the last limit of its speed. He startled the Mexican farmers in their little jacals along the road as he went dashing past with thunder of hoofs and swirls of dust. Into the pleasant valley of the Bonito he came at last and without drawing rein burst into Lincoln, his sweat-lathered horse staggering with exhaustion.

There was much to be done and no time to lose. With quick decision, Garrett organized his plans to hunt down the escaped outlaw. He gathered a posse of a dozen picked men in Lincoln. He rushed off orders for other posses to take the filed from Roswell, Tularosa, and Seven Rivers. He had only a vague idea of the direction the Kid had taken. He could only guess at what place of refuse the fugitive would aim. Every avenue of escape out of the country must be guarded. The dragnet was to be far-flung. The sheriff proposed in his search to comb New Mexico.

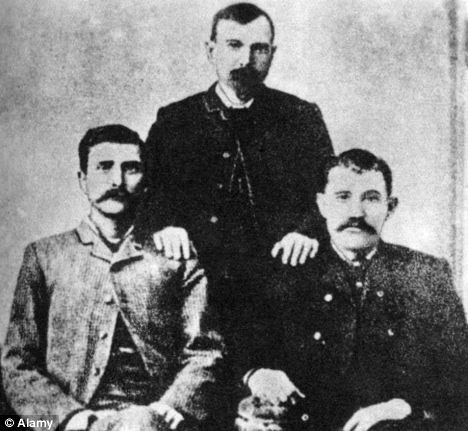

(from left) Lincoln County sheriffs Pat Garrett, James Brent and John W. Poe. Upon hearing the news of the Kid’s escape from Lincoln County jail, Garrett said to Poe: ‘Ain’t that hell? I told those fellows to watch the Kid. They must have got careless. Now they’re dead and the Kid’s gone. That means I’ve got to do it all over again. Now I’ve got to kill the Kid or get killed trying.’The hour for the start was set. The posse assembled in the sheriff’s office in Lincoln courthouse for a final council of war.

“I figure,” said Garrett, “the Kid’s headed’ for old Mexico. Once across the border, he’ll be safe. Our only chance it to head him off before he gets there. With good luck, we can do it.”

“I got an idea the Kid might hole up in Fort Sumner,” interposed Former Sheriff “Dad” Pippin.

“No chance,” retorted Garrett. “Fort Sumner’s only ninety miles. The Kid’s no fool. He won’t hang around so close, with posses rakin’ the whole country for him and knowin’ he’s going to swing if he’s caught.”

“That’s just it,” Pippin answered. “He might calculate you’d think just that way.”

“The Kid’s too smart to take a chance like that.”

“If you don’t aim to look for him in Fort Sumner, I’d call it mighty smart for him to go there. He’d be among his friends.”

“That’s true enough. He’s got plenty of friends there. But I don’t know as he’d trust ‘em. There’s that big reward out for him dead or alive. Money has been known to turn friends.”

“What’s more,” persisted Pippin, “he’s got a sweetheart in Fort Sumner.”

“What does the Kid care about sweethearts?” Garrett replied with scorn. “He’s thinkin’ of no sweethearts. He’s figurin’ right now on savin’ his neck from the noose. I tell you he’s ridin’ hard for the Rio Grande. His only hope is Mexico.”

“Well, you’re bossin’ the job,” said Pippin, “and that settles the argument.”

When Sheriff ‘Dad’ Pippin suggested Billy the Kid might be holed up in Fort Sumner, where he was known to have a sweetheart, Sheriff Pat Garrett dismissed the idea. ‘What does the Kid care about sweethearts?’ Garrett said. ‘He’s thinkin’ of no sweethearts. He’s figurin’ right now on savin’ his neck from the noose. I tell you he’s ridin’ hard for the Rio Grande. His only hope is Mexico.’“One last word before we hit the trail, boys,” added the sheriff. “The Kid’s desperate. He ain’t goin’ to be taken alive. You can gamble on that. If we jump him, we’ve got to kill him. Don’t take any chances. As soon as you sight him, start shootin’.”

Westward went the posse, into the vastness of deserts and mountains

So westward out of Lincoln rode Sheriff Garrett and his posse, gaunt, hawk-eyed men, bronzed with weather, six-shooters jostling in scabbards, sun flashing on rifles, their hunting field New Mexico, their quarry a slender youth, five feet eight in his boots, hidden somewhere out in the vastness of deserts and mountains.

‘They passed out of the hills and scoured the Carrizozo plains and the desolate Mal Pais beyond…They followed the Kid’s trail without knowing it to the point where he had turned off into Boca road toward Fort Sumner. As Garrett had thrown Fort Sumner out of his calculations they kept on west. Spreading out, they ransacked the mountain coverts around Fort Stanton where the Kid once had had a rendezvous. They passed out of the hills and scoured the Carrizozo plains and the desolate Mal Pais beyond. They beat across the ghastly, gleaming chaos of White Sands. For and wide over the somber lava desert which an ancient crater spread along the slopes of the Oscuros--a black wilderness of jagged iron rocks sentinelled by weird cactus shapes--they circled and quartered like foxhounds questing on a cold trail. They whipped the wild ravines of Chupadero Mesa. They searched among the ruins of the Gran Quiveca. Turning south, they passed through the Three Rivers country, traversed the Jornado del Muerto, explored the canons and valleys of the Organ Mountains, and came at the end of a bootless hunt into Mesilla. Not a clue had they found, not a word had they heard of the Kid’s whereabouts. So, weary, discouraged, and bedraggled, they trooped back to Lincoln.

The other posses reported equally unsuccessful results. But Garrett was not yet ready to give up. He had one more card to play. From the Mescalero reservation he summoned two Apache trailers, lithe, half-naked, moccasined fellows, famous among their people for skill in tracking game and men through trackless wastes. Given the direction of the Kid’s flight, these human sleuth-hounds set out from Lincoln on foot. Along the sides of the road they worked slowly, patiently, their keen eyes scrutinizing every inch of ground, until they came to the trail that branched off to Baca Cañon. To Padilla’s ranch they came at length, led by what microscopic trail markers no man might know except themselves. Padilla, good friend of the Kid that he was, kept a silent tongue in his head. Beyond his jacal, the Indians lost the scent. Turning back to Lincoln, they reported the trail was too old and too cold to follow.

So the man-hunt ended and Garrett settled down to watch and wait. Sooner or later news would reach him. A rumour would come on the wind out of the dark. Something somewhere somehow would happen. In some lonely bar over the whisky glasses a tongue would wag. Out in the vagueness of the Southwest, a leaf would rustle, a twig would crack. Abruptly the empty silence would find a voice. The Kid’s hiding place would be betrayed. Sooner or later. But for the time being, the outlaw had disappeared as if the mountains had opened and engulfed him.

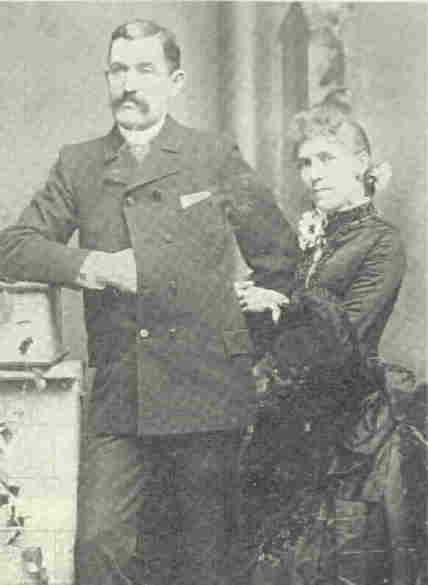

Deputy John W. Poe, appointed by Pat Garrett, with his wife Sophia, circa 1883. ‘A remarkable man was Poe with record behind him and a future ahead. Standing more than six feet in height, broad shouldered, and as straight as a mountain pine, he was a determined, resourceful man with courage and honesty clearly legible in his frank face and clear blue eyes.’Poe, who had been appointed one of Garrett’s deputies, remained in White Oaks during May and June busy on the Coughlin case. A remarkable man was Poe with record behind him and a future ahead. Standing more than six feet in height, broad shouldered, and as straight as a mountain pine, he was a determined, resourceful man with courage and honesty clearly legible in his frank face and clear blue eyes. A native of Kentucky, he had lived in Texas since early manhood. As marshal of Tascosa, hard-boiled cowboy capital of the Panhandle, he had established a reputation for fearless performance of duty. When Jim Oglesby, bad man from the Indian Nations, was painting the town, Poe, without drawing a weapon, disarmed him in mid-rampage and led him off tamely to the calaboose. When infuriated citizens surrounded him, and threatened to lynch a prisoner in his custody, Poe, standing alone, drew his six-shooter and told them they would have to kill him first and some of them would die before he did; his quiet heroism bringing the mob to its senses and saving the day. He moved later to Mobeetie, lively little town of the Texas cattle rangers, and was appointed by the Canadian River Cattleman’s Association to ferret out and bring to justice the rich patrons of Billy the Kid, who supported that young outlaw in his rustling operations by buying his stolen cattle. His campaign against Pat Coughlin, King of Tularosa, was his first successful work as a cattle detective in New Mexico.

‘Billy the Kid is in Fort Sumner!’

There dwelt in White Oaks a certain George Graham, who was living out the age-old tragedy of a drunkard. He had once been a man of substance in Texas. But drink and dissipation had played havoc with his means, he had slipped gradually into the depths and was now a down-at-heels derelict making shift to exist as a hanger-on around White Oaks saloons and gambling halls. In more prosperous days, he had known Sam and Dan Dedrick, who kept a livery barn in the mining camp. Since what few coins he managed to scrape together went for whisky and he had no money to pay for a bed, they permitted him, out of charity, to sleep in the haymow of their establishment.

One night in July, two months after Billy the Kid had escaped, Graham crawled into the hay and composed himself for slumber. He was just dozing off when he heard voices in the livery office. He pricked up his ears. The Dedrick brothers were talking together. They exchanged confidences. Evidently in the silence and acclusion of their livery barn at midnight they felt no fear of eavesdroppers. For the moment they had forgotten the derelict stretched in the bay.

What Graham heard started him into intense wakefulness. He became suddenly aware that he was the possessor of a dangerous secret. The thought troubled him. For hour he tossed in nervous restlessness. It was not until the small hours of morning that he was able to fall asleep.

Billy the Kid (center) with his second gang, known as The Rustlers, as depicted on the 1992 issue of The Outlaw Gazette: (from left) Tom O'Folliard, Charlie Bowdre (both Folliard and Bowdre were shot and killed by Pat Garrett amd buried side by side; later they were joined in their gravesite by Billy the Kid, also killed by Garrett), Tom Pickett, Billy the Kid, Dirty Dave Rudabaugh and Billy Wilson. Brothers Sam and Dan Dedrick were allies of the Rustlers, each allowing the gang to store stolen cattles at their Bosque Grand Ranch (Dan) and livery stable in White Oaks (Sam). It was the brothers’ loose talk in a White Oaks saloon that tipped off derelict George Graham to the Kid’s presence in Fort Sumner, information Graham promptly relayed to deputy John W. Poe, who in turn took it to Pat Garrett, thus sealing the Kid’s fate.Standing on the street next day, Poe was speculating idly on the enigma of the Kid’s disappearance. Garrett, it seemed, was right. The Kid by this time was doubtless safe across the border in Mexico. Well, at least he would not come back to harry Canadian River herds, and Poe’s employers were as well off as though the Kid had been hanged. A trampish man slouched by. Poe rested a casual eye upon him. He had no idea who the fellow was. From the looks of him, he didn’t care to know. But to Poe’s surprise, the seedy stranger flashed him a look of recognition and, with an almost imperceptible motion of the head, tipped him a signal to follow. Here was a mystery which at first glance did not seem intriguing. But Poe followed--first to the edge of the town and then on a little way into the country. At a point in the road screened from observation by piñon trees, the vagabond turned and faced him.

“Do you remember me?” he asked.

Poe, after a moment’s scrutiny, shook his head.

“George Calhoun.”

“Oh, yes,” answered Poe. “Back in Tascosa. Of course. How are you, George?”

“Down and out. That’s how I am. Which it’s no use to tell you. You can see it.”

“What’s the matter?”

“This what drink has done to a man who was once a fairly prosperous citizen. But I didn’t bring you out here to tell you my troubles. You were my friend in Tascosa. I have news for you. I know what you’re here for.”

This mysterious fellow was talking in riddles. Poe wondered if his misfortunes might not have unhinged his mind.

“But I’d be killed if it was ever found out I told you,” Graham added. “You must give me your word you’ll never mention my name.”

Poe promised secrecy.

Graham looked in all directions to make sure no one was in sight.

“All right,” he said. “Here it is. Billy the Kid is in Fort Sumner!”

The words gave Poe a thrill.

“What makes you think that?” he asked.

“Listen. You know the Dedrick boys? They have been friends of the Kid for years. The Kid used to hang out at their ranch over in the Bosque Grande country. Whenever he came to White Oaks he made their livery stable his headquarters. Last night, when I had gone to bed in the haymow, I overheard Sam and Dan Dedrick speaking about the Kid. They know where he is. They said he has been in White Oaks since his escape at Lincoln.”

Poe smiled incredulously.

“I’m telling you what they said,” insisted Graham. “Believe it or not. The Kid, they said, has been right here in White Oaks. They kept him hid in their livery barn several days. What do you think of that? And you walking past the barn a dozen times a day and within a few feet of him. Ever since he killed his guards and got away, the Kid, the Dedricks said, had been hanging around Fort Sumner. Expects to skip to Mexico some time soon. But he hasn’t gone yet. He’s in Fort Sumner now.”

Poe hardly knew what to think. The information was, at least, impressive.

“What you tell me may be true,” he said at length. “But it’s hard to believe. However, it may be worth investigating. Here’s a dollar for you. Go buy yourself a few drinks.”

So Billy the Kid was betrayed for a silver dollar by a rum-soaked bum of the boozing-kens. Four drinks of whisky, according current quotations in White Oaks bars, was the price paid for the secrecy upon which his life hung as by a hair.

Poe walked in on Garrett in Lincoln the next day.

“I don’t believe it,” said Garrett.

“Neither do I,” replied Poe. “But let’s take a chance.”

“Humph!” Garrett rubbed his nose reflectively. “Well, we’ll go. But I warn you it’ll be just another wild-goose chase.”

Sheriff Garrett and Poe rode into Roswell next day and laid the clue before Tip McKinley, one of Garrett’s deputies, a veteran man-hunter hailing from Uvalde in Texas.

“I don’t take any more stock in it than you fellows,” said McKinney. “There’s about as much chance of the Kid being in Fort Sumner as of my flying to the moon.”

But that evening at sundown the expedition of the three skeptics started from Roswell. They headed towards Lincoln to avert suspicion as to their destination. Ten miles out, they turned sharply to the north. That way Fort Sumner lay.

‘Billy the Kid must be a fine fellow…’

They rode till midnight, when they picketed their horses and slept on their saddle-blankets. Next day they travelled fifty-five miles and camped for the night in the sandhills six miles from Fort Sumner.

“One of you ought to ride into Fort Sumner now and reconnoiter,” said Garrett. “Nose around. Take a drink or two at old Beaver Smith’s bar and talk with the fellows. Might learn something if there’s anything to learn. But I can’t go. Everybody knows me. I lived there two years.”

“I can’t either,” spoke up McKinney. “I’ve been here half-a-dozen times, and quite a few know me.”

“Nobody knows me,” said Poe. “I’ll go.”

“If you don’t pick up any information in Fort Sumner,” said Garrett, “ride on to Charlie Rudolph’s ranch seven miles out on the Las Vegas road. Charlie’s an old-timer and a friend of mine and you can lay your cards on the table with him. If the Kid’s in the country, he’ll tell you. I’ll give you a note to him.”

Garrett tore a page out of his pocket notebook, scratched off a few lines to Rudolph and gave the paper to Poe.

“McKinney and I will wait here in the sandhills for you until dark,” he added. “If you don’t come back, we’ll ride to the end of the double row of cottonwoods four miles north of Fort Sumner near the little Mexican village of Punta de la Glorietta and meet you there at nine o’clock.”

It was ten o’clock in the morning of July 14th when Poe rode into Fort Sumner and hitched his horse in front of Beaver Smith’s saloon. The grizzled old proprietor stood in the door.

‘Warm day,” observed Poe ingratiatingly.

“Where you from?” asked old Beaver, waiving formalities.

“White Oaks.”

“Live there?”

“Been doing a little mining. Not much luck. On the way back to my home in Mobeetie.”

The little street had been empty when Poe arrived. Now he noted men strolling toward him with a casual air from all directions. He was soon surrounded by a dozen citizens, all wearing six-shooters, all viewing him with cold-eyed suspicion.

“Stranger in these parts?”

“Where you from?”

“Where you bound?”

They were violating the frontier’s code of courtesy in which questions to a stranger had no part. Being a frontiersman, Poe knew it. Also he knew why. But he answered their queries with easy politeness as he had answered Beaver Smith’s.

“Come on in and let’s have a drink,” he suggested.

After the whisky the situation eased a trifle. Poe discussed crops. He had a word to say about cattle. He dropped a few wise reflections on politics.

“Pat Garrett,” he remarked at last, slipping in the parenthesis rather adroitly, “was in White Oaks the day I left, looking for the Kid. They say the Kid’s been down there since his escape.”

Sudden profound silence greeted his observation. His auditors looked at him sullenly and shot furtive glances at one another. Poe went back to crops, cattle, and politics for an hour or so. Then he tried again.

“Billy the Kid must be a fine fellow,” he said, taking new tack. “I don’t know anything about him, being a stranger in New Mexico. But I’ve been interested in the stories I’ve heard. They say he has a sweetheart in Fort Sumner and paid her a flying visit after he broke jail. Eh?”

Another profound silence shot through with suspicion. It was plain Poe could learn nothing. These were all friends of the Kid. Whatever they knew they were keeping to themselves. To save his visit from being a total loss, Poe went to a restaurant and ate a good meal. He had had no food except a pocket sandwich since leaving Roswell.

Poe left Fort Sumner in the middle of the afternoon, starting eastward. A few miles out, he cut across country westward to the Las Vegas road on which Rudolph’s ranch was located. He arrived at Rudolph’s at sundown, presented Garrett’s note, and was cordially received.

After supper the two men sat on the porch in casual conversation. Poe’s first mention of Billy the Kid had a marked effect upon his host. Rudolph fidgeted in his chair and tried to change the subject.

“I’ve heard,” remarked Poe relentlessly, “the Kid’s been in hiding in Fort Sumner ever since his escape.”

“No truth to that,” snapped Rudolph with notable perturbation. “Such a report is silly. The Kid’s too shrewd to be caught lingering around here with a price on his head and posses hunting him everywhere.”

Poe played cautiously a little longer and then, following Garrett’s advice, laid his cards on the table.

“Sheriff Garrett,” he said, “is waiting for me now near Fort Sumner. We have reason to believe the Kid is there. Garrett has sent me to you for definitive information as to the Kid’s hiding place. I’d like the straight truth from you.”

“I know nothing about the Kid,” Rudolph protested, his excitement changing to downright alarm. “I can’t tell you a thing. If the Kid was around here and I told you where he could be found, my life wouldn’t be worth a penny. But I don’t believe he’s around Fort Sumner. You can set that report down as a lie.”

Poe joined Garrett and McKinney at nine o’clock that night at the appointed meeting place at the north end of the double row of cottonwoods and recounted his day’s experiences. The suspicion he encountered in Fort Sumner and Rudolph’s agitation convinced him, he said, that the Kid was somewhere in the Fort Sumner vicintage. Garrett was not so sanguine.

“But a long as we are here,” Garrett said, “we might was well try watching Charlie Bowdre’s old home in Fort Sumner. Manuela Bowdre, Charlie Bowdre’s widow, still lives there with her mother, and if the Kid’s in these parts, he’s probably hiding there.”

‘I’m willing to bet the Kid ain’t in Fort Sumner…’

They set off from Fort Sumner through the four-mile avenue of cottonwoods. A quarter of a mile from town, they hid their horses in a grove of trees on the Pecos and took a position in the old peach orchard at the north edge of the village. Just across the road from their place of concealment stood the old military hospital I which Manuela Bowdre had her home. A full moon was in the sky, making the landscape as bright as day, but the peach trees were in full leaf, and in the deep shadows they were safe from chance discovery. For two hours they remained there silently watching the Bowdre door like three cats at a mouse hole. But no sign of the Kid rewarded their patience. It was hard on midnight when they decided to abandon their vigil.

“I had no faith in this trip in the first place,” growled Garrett. “I’m willing to bet the Kid ain’t in Fort Sumner and never has been here since his escape. We’ll go back to our horses now and start for Roswell. Best to put a little distance between us and Fort Sumner before daybreak.”

“Let’s go see Pete Maxwell before we give it up,” insisted Poe doggedly. “If the Kid’s in Fort Sumner or has been here, he’ll know beyond a doubt. Maybe he’ll tell us.”

“Maybe,” replied Garrett dubiously, “and maybe he won’t. If the Kid happened to hear Maxwell had betrayed him, Pete would be due to start on a long journey. But just to satisfy you, Poe, we’ll see him.”

They crossed the road, white with moonlight, slipped into the sleeping town, stole noiselessly through the streets in the shadows of the houses, and came out into the broad open space that had once been the parade ground of the army post. Before them stood the Maxwell home.

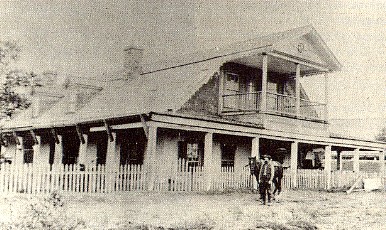

Pete Maxwell’s house, circa 1882, the year after Pat Garrett shot Billy the Kid in Maxwell’s bedroom, the first left corner room just beyond the gate and behind the pillar. (Photo: R.G. McCubbin Collection)Once used as officers’ quarters, it was a large two-story building containing twenty rooms, its lower walls of adobe bricks sustaining a frame superstructure with a row of dormer windows along its gable roof opening from the upper rooms. A wide shuttered veranda ran across its front and along the north and south sides. It faced east on the old parade ground, from which it was separated by a low picket fence that extended fifty feet to the south to a arrow of adobe houses along the side yard. A cannon, relic of old soldier days, stood outside the fence near the northeast corner. At the southeast corner beside the front gate grew a tall cottonwood tree.

“Pete Maxwell’s sleeping room is right there in the southeast corner of the house,” said Garrett when they reached the gate. “You fellows wait here outside and I’ll go in and have a talk with him.”

Pete MaxwellGarrett stepped across the porch and entered the door of Maxwell’s room which, on this warm summer night, had been left open. Poe sat down on the edge of the porch at the gateway. McKinney squatted down on his heels, cowboy fashion, just outside the picket fence and rolled himself a cigarette. The moon was riding westward from the zenith and the two men, sitting in silence, merged into the dark, heavy shadows falling eastward from the building.

Maxwell’s room was in deep darkness. Garrett paused just inside the door for a moment until his eyes grew accustomed to the obscurity. Then, groping his way to a chair at the head of the bed, he sat down and gently roused Maxwell.

The room was twenty feet square. There were three windows, two in the front and one in the south wall near the door, but the roof of the porch prevented even a faint reflection of moonlight from entering. Maxwell’s bed stood against the south wall, its floor near the door, its head against the front wall. There was a bureau in the northwest corner, a fireplace in the west wall, and a washstand between the fireplace and the door. The floor was carpeted.

Maxwell was surprised when he awoke from a deep sleep and saw Garrett sitting at his bedside. He rubbed his eyes.

“Oh, hello, Pat,” he mumbled. “Qué hace Usted aquí?”

“About the Kid, Pete,” said Garrett in Spanish. “I’ve had word--“

A voice sounded outside—a voice that Garrett knew. He cut short his words. He sat in tense, sudden silence, listening…

When Garrett and his deputies stole into Fort Sumner from the peach orchard, Billy the Kid was in the house of Saval Gutierrez, Pat Garrett’s brother-in-law, which stood at the south edge of the Maxwell side yard not more than fifty feet from the Maxwell home. He had come in only a few minutes before from a sheep ranch several miles south on the Pecos. He was tired. He took off his coat, and hat and threw himself on a bed. He smiled to himself as he thought how neatly he had thrown Garrett off the scent. While the posses were sweeping New Mexico, he had been safe in Fort Sumner among friend. But it was time for him to get out of the country. These bloodhounds on his trail would nose him out sooner or later. He would start for Mexico tomorrow night. And while the Kid dreamed his dream, death was waiting in ambush for him fifty feet away.

“Celsa,” he called.

Celsa Gutierrez, Saval’s wife, who had been waiting up for the Kid to come in from the sheep camp, stepped into the room from the kitchen.

“I’m hungry, Celsa,” said the Kid. “Can’t you get me a bite to eat?”

Celsa rummaged through her pantry.

“There is nothing here but some cold tortillas and coffee, Chiquito,” she said, “but Pete Maxwell killed a beef today. It is hanging in the north porch of the Maxwell house. I’ll go cut you off a steak and cook you a good supper.”

She went back into the kitchen and got her butcher knife. She was reaching for her rebozo hanging on a nail on the wall to throw over her head against the night’s damp.

“I’ll go for the meat,” said the Kid, getting up from the bed.

“No, muchacho,” protested Celsa. “You must stay here. There is no telling what might happen to you. Danger is always near you. You must not venture out tonight.”

On this night of nights, Fate, it might seem, was setting the stage. There was no need for the Kid to come in from the sheep camp. But he had come. There was no need for him to go for the meat. But he went.

“There is no danger, Celsa,” he said. “Give me the butcher knife.”

So the Kid started out for the meat just as he was, bareheaded, coatless, with only socks on his feet, the butcher knife in his right hand and, naturally enough, as he was left-handed, his forty-one caliber double-action revolver in its scabbard at his left side. He stepped from the door of Saval Gutierrez’s home not more than a minute after Garrett had entered Pete Maxwell’s room.

The familiar scene outdoors was more than usually serene in the pale moonlight. The deep hush of midnight lay upon the slumbering town. The great, dark, silent mass of the Maxwell home loomed fifty feet ahead of him. There was no movement, no sound to indicate danger, nothing to warn him to be on guard. He was hungry. The carcass of beef hung in the north porch. He would cut off a good steak for himself. There was no better cook at Fort Sumner than Celsa. He would have a regular feast. … He did not see the two deputies sitting in the heavy shadows of the porch. With quick, easy stride, still thinking of his supper, he walked straight toward them, his soul off watch.

Poe saw him coming. McKinney, squatting behind the palings rolling a cigarette, neither saw nor heard him. The Kid’s figure stood out clearly in the moonlight as he moved noiselessly on bootless feet over the matted grass. Not a flash of suspicion disturbed Poe’s mind that this was the desperado he was hunting, whom he knew he had to kill on sight, who otherwise would kill him instantly and without mercy. Strangely enough at this tense, critical moment of the long chase, the deputy’s wits seem to have been wool-gathering. He looked at the approaching figure with only casual interest, wondered in a mildly curious way who this half-dressed youth might be wandering about at midnight, and contented himself with the half-formed, passing thought that probably it was one of Pete Maxwell’s sheep herders.

Coming on rapidly, the Kid stepped up on the porch and almost stumbled over Poe before he saw him. If his soul had been off watch before, that instant it sprang to hair-trigger alertness. There was a lightning-quick movement of his left hand and Poe was staring in astonishment into the muzzle of the Kid’s revolver.

“Quién es?”

The Kid’s voice was vibrant with a suddenly awakened sense of danger. Who were these two armed strangers at Pete Maxwell’s house at midnight? He began to back away across the porch.

Poe was nonplussed, his mind somehow still out of focus. He thought with a certain touch of pity that, without intention, he had frightened this poor sheep herder. It seemed to him vaguely that he owed the simple rustic some sort of apology. He got to his feet and took a step toward the Kid.

“Don’t be scared,” he said reassuringly. “I’m not going to hurt you.”

The Kid kept backing away.

“Quién es?”he snapped out again.

Poe said nothing more. He did not know what to say. He had never seen a sheep herder act like this. The fellow must be crazy. It did not occur to him to draw his six-shooter. He stood there feeling rather foolish, the Kid’s gun all the while pointed at his heart. McKinney had stepped up on the porch and was standing now a pace behind Poe. He, too, fancied the Kid a sheep herder and was equally at a loss to understand the situation.

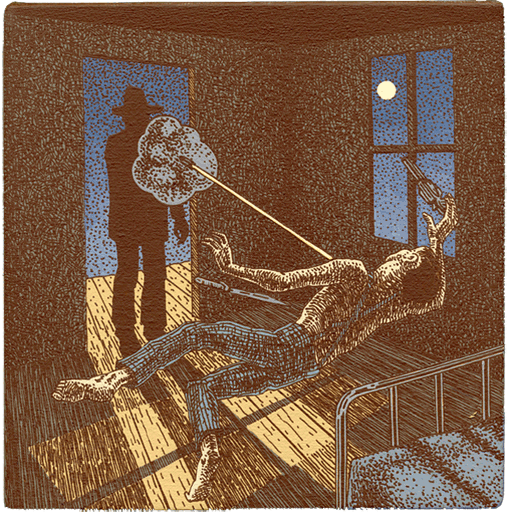

The Kid backed into the doorway of Maxwell’s room. There he paused for an instant, half-hidden by the thick adobe wall, his gun still at aim.

“Quién es?” he called a third time.

Then he turned and stepped into the black darkness of the chamber; into security, as he fancied; into a death trap, in reality. In the darkness, Death crouched, waiting, ready.

Coming in out of the bright moonlight, the Kid could hardly see his hand before him. But he did not need to see. He knew the room of old, the arrangement of the furniture--every detail. He groped to the foot of the bed, stepped around to the side, leaned slightly over Maxwell

“Quién es son esos hombres afuera, Pete?” he asked. (Who are those fellows outside?”)

Garrett, sitting silent in the darkness at the head of the bed, could have stretched out a hand and touched the Kid. He knew at once this was the Kid. He had recognized his voice when the Kid had flashed his first Spanish question at Poe outside on the porch. He had recognized the familiar figure silhouetted against a patch of moonlight as the Kid came in the door. If no doubt was in his mind of the Kid’s identity, neither was there doubt as to what he himself must do and do quickly if he was to live to see the light of another day. His mind was instantly made up.

As the Kid entered, Garrett, still sitting in his chair, reached for his six-shooter. But so quickly did thle little drama in the darkness rush to its climax, he was still in the act of drawing his weapon from its scabbard when the Kid, two feet away, was bending over Maxwell with the query that was never answered. The Kid felt, rather than saw, the noiseless movement of Garrett’s arm. He caught a sudden, vague glimpse of Garrett’s form bulking dimly in the darkness. He sprang back to the middle of the room and threw his revolver to a level.

“Quién es?” he demanded sharply.

Dropping over sideways from the chair toward the floor in a tricky, dodging movement, Garrett answered the question with a shot. A flare of lurid flame lighted up the darkness for an instant, the room shook with a sudden crashing explosion, and Billy the Kid fell dead with a bullet through his heart.

Garrett fired a second shot as quickly as his finger could pull the trigger and, bolting for the door, was out of the room in three strides. Pete Maxwell, in wild panic, scrambled over the foot of his bed and, hard on Garrett’s heels, dashed outside, a fat, ludicrous figure clad only in his nightshirt. He blundered on the porch into Poe, who shoved his six-shooter into his stomach and would have killed him, had not Garrett, with a hurried explanation, knocked the weapon aside.

“It was the Kid who come in there on to me,” Garrett told Poe, “and I think I got him.”

“Pat,” replied Poe, still under the sheep-herder hallucination, “I believe you have killed the wrong man.”

“I’m sure it was the Kid,” responded Garrett, “for I knew his voice and could not have been mistaken.”

They heard several gurgling gasps inside. Then there was silence. But no one dared enter that room of death. A spectre of fear stood in the darkness like the menacing ghost of the dead.

Paulita Maxwell, aroused from sleep, came out on the porch and joined the four men huddled along the wall. They broke the news to her. She received it in silence without show of emotions. Pete Maxwell hurried into the house and returned with a tallow candle. Also with trousers on. He reached out a cautious hand and set the lighted taper on the window sill. Peeping furtively into the room now faintly illuminated by the flickering flame, he saw the Kid stretched out face downward in the centre of the floor.

They went in then. Upon examining the body they found that Garrett’s first bullet had struck the Kid directly over the heart, a centre shot, passing through him and burying itself in the west wall. What had become of his second bullet they were at that time unable to discover. The Kid had not fired a shot. He lay with his gun still clutched in his left hand and, in his right, Celsa Gutierrez’s kitchen butcher knife. Every cartridge chamber of his revolver was loaded.

Paulita Maxwell, aroused from sleep, came out on the porch and the four men huddled along the wall. They broke the news to her. She received it in silence without show of emotion. Pete Maxwell hurried into the house and returned with a tallow candle. Also with trousers on. He reached out a cautious hand and set the lighted taper on the window sill. Peeping furtively into the room now faintly illuminated by the flickering flame, he saw the Kid stretched out face downward in the centre of the floor.

They went in then. Upon examining the body they found that Garrett’s first bullet had struck the Kid directly over the heart, a centre shot, passing through him and burying itself in the west wall. What had become of his second bullet they were at that time unable to discover. The Kid had not fired a shot. He lay with his gun still clutched in his left hand and, in his right, Celsa Gutierrez’s kitchen butcher knife. Every cartridge chamber of his revolver was loaded.

They carried the body across the Maxwell yard into a deserted carpenter shop, full of dust and cobwebs, its floor littered with shavings, and laid it on an old work bench. The town was aroused by now. Excited Mexican men and women gathered at the scene and crowded into the shop. When the women saw the Kid lying dead, the moon shining on his white face through a weather-stained window, they broke into a hysteria of tears and grief, filling the place with their cries. Celsa Gutierrez screamed as one demented. Abrama Garcia, a figure of tragedy, pale with fury, shook her clenched fists aloft, called down curses on Pat Garrett, shouted threats to kill him. Deluvina Maxwell, the Navajo servant of the Maxwell household, whose idol the Kid had been, burst into a passion of sobs. Throwing her arms about the Kid, she covered his face with her tears. “Mi muchacho!” she wailed, “mi pobre muchacho!”

Bringing candles, the women lighted them about the body. In the shine of the candles, the Kid lay all night in rude state, the dusty work bench for his bier. And all night the women in their black dresses, with their black rebozos about their heads, crouched along the walls in the dim, dingy room, weeping.

It was a wild night in Fort Sumner. Men stood in groups in the street and about the Maxwell home. All had six-shooters. Some had rifles. They discussed the Kid’s death in muttered undertones. “Shot down in the dark.” “Never had a chance.” “Nothing but straight murder.” They worked themselves up to a fever pitch of excitement. They threatened vengeance. Garrett, Poe, and McKinney sat until daybreak in a room in the Maxwell home, their guns in their hands ready for instant action. They expected an attack from the Kid’s friends. But no openly hostile demonstrations developed. After the inquest next morning, held by a justice of the peace, they mounted their horses and set off for Roswell, their departure watched by grim, sullen groups that hurled savage imprecations after them.

What became of Garrett’s second bullet remained an unsolved enigma for years. No trace of it and no mark it had left could be found. Finally it was discovered embedded in the underside of the top of the washstand which had stood across the room from Garrett. From the angle at which it had struck, it must have been fired almost from the level of the floor when Garrett dropped over sideways from his chair. The twisted lump of lead bore silent and unmistakable witness to a panic. It must have missed the Kid by six feet.

Calm analysis of the tragedy reveals unaccountable blunders. The Kid made two egregious mistakes and, though the explanation of each is obvious, both were out of keeping with his usual methods and his desperate character. He could have killed Poe and McKinney when he had them covered on the porch. He could have killed Garrett when he threw down his gun on his shadowy form in the darkness. These were two chances to save his life; he took advantage of neither. It is evident that the dubious thought that the three men might be friends of Maxwell’s bent upon some peaceful mission stayed the Kid’s deadly trigger finger. It would have been more like his true self to shoot first and ask questions afterward. Yet he did nothing but ask questions. He hesitated, perhaps for the first time in his life, and death was the result of his hesitation. According to Poe, not more than thirty seconds elapsed from the moment the Kid entered Maxwell’s room until he was killed. Blundering strangely from the beginning of the episode to its fatal termination, the Kid, in his last flash of consciousness, it is safe to say, did not know who killed him.

The mistake credited to Poe and McKinney savours of a momentary aberration in view of the time, place, and circumstances. Their failure to suspect the Kid’s identity is incomprehensible and their persistence in the belief that he was a harmless sheep herder, even after he had jerked out his gun, seems sheer stupidity. Both were men of fine minds, and their dullness in such a desperate crisis is hard to explain. Either could have killed the Kid as he came toward them in the moonlight except for this singular apathy. Only the Kid’s own blunder kept their mistake from costing their lives.

Though the cards were stacked against the Kid that night and it was written in the stars that he must die, Garrett was the only one of the four principals in the tragedy who acted as he might logically have been expected to act and as the occasion demanded he should act. Everything he did and everything he did not do proved the shrewdness and craft of an alert, quick thinking brain. If he had spoken, the Kid would have recognized him by his voice. If he had risen from his chair, the Kid would have recognized him by his height. In either case, he would have died instantly. But Garrett did not speak, did not rise, did not hesitate. He fired. He alone made no mistake.

Fort Sumner had been home to the Kid, if under Heaven he had had a home, and the last rites were a labour of love in which all Fort Sumner joined. Domingo Lubacher, man of all work, knocked together a coffin of rough pine boards. Francisco Medina, who still lives on the ranch of Don Maneul Abreu, dug the grave. The hearse was a rickety old wagon drawn by a pair of scrawny Mexican ponies. Not six people were left in Fort Sumner during the funeral. The entire population, men, women, and children, turned out to do the Kid last honours and followed his corpse to the little military cemetery a short distance east of town. A stranger might have thought the funeral that of Fort Sumner’s most distinguished citizen.

They laid the Kid to rest beside Charlie Bowdre and Tom O’Folliard, his old-time comrades in many a foray and desperate adventure. His grave was at one end of the row, O’Folliard’s at the other, and Bowdre’s in the middle. Pat Garrett had killed them all. At the head of the little mound set a wooden cross on which was painted in crude zigzag letters, “Billy the Kid.”

The row of three graves in the little cemetery on the windswept, desolate river flats marked the end of the long campaign to establish law and order west of the Pecos. The Kid was dead; his outlaw band was wiped out. Sheriff Garrett’s work was done.

***

Postscript: Where ‘The Boy of the Tiger Heart’ Rests In Peace

Billy the Kid’s grave today, on the site of old Fort SumnerWhen Walter Noble Burns was doing his research for the book that became The Saga of Billy the Kid, he befriended Charlie Foot, “a white-haired, white-moustached, kindly old philosopher; a good, steady-going, old-time Western man, who has seen hard knocks in his day and emerged out of rough pioneer experiences into a mellow old age.” A resident of old Fort Sumner for more than forty years, Foot had run a saloon there, and had in fact served twenty years as postmaster. “He knows the old place like a book,” Burns wrote in his own book. Foot took Burns around the remains of old Fort Sumner, now barren and deserted, returning to the grass and dust it had been before the Fort was built. The once-grand military cemetery where Billy the Kid had been buried had been closed when the government shut down the Fort and the soldiers’ bodies moved to a national cemetery in Santa Fé. Its adobe wall and arched gateway marking it as a solemn place for contemplation and reflection—“a decent spot for dead men to sleep in,” as Charlie Foot said—were torn down. Only bad men and some of their victims were left behind, most in unmarked graves in an area marked off by a barbed-wire fence—a half-acre of half-desert land the locals referred to as “Hell’s Half-Acre.”

“It might pass at a glance for an abandoned cattle corral,” Burns wrote. “The flat ground is sparsely covered with salt grass, bunch-grass, prickly pear, sagebrush, greasewood, and Spanish gourd. Here and there are half-wrecked paling enclosures about neglected graves; here and there, broken, mouldering crosses half fallen or leaning at crazy angles. In the summer sunshine, the place looks God-forsaken; a mocking bird singing happily on a fence post fails to relieve its grimness. On a leaden day of cold rain, it is the concentrated essence of loneliness and desolation. When winds are asweep through the Pecos Valley, they whimper and moan in the barbed-wire fence like troubled ghosts.”

Charlie Foot takes Burns to the spot where Billy the Kid is buried. “With a knotted forefinger he points down to a strip of flat, yellow, sun-cracked earth that is strangely bare.

“‘This is the spot,” says the old man. ‘Under this strip of baked clay lies Billy the Kid.’”

The bare space is perhaps the length of a man’s body. Salt grass grows in a mat all around it, but queerly enough stops short at the edges and not a blade sprouts upon it. A Spanish gourd vine with ghostly gray pointed leaves stretches its trailing length toward the blighted spot but, within a few inches of its margin, veers sharply off to one side as if with conscious purpose to avoid contagion. Perfectly bare the space is except for a shoot of prickly pear that crawls across it like a green snake; a gnarled, bristly, heat-cursed desert cactus crawling like a snake across the heart of Billy the Kid.

“‘It’s always been like this,’ say Old Man Foot, standing back from the spot as if half-afraid of some inexplicable contamination. ‘I don’t know why. Grass or nothin’ else won’t grow on it—that’s all. You might almost think there’s poison in the ground.’

‘I reckon if you dug down under there, you wouldn’t find much of the Kid left. It’s more than forty years since they put him away. You might, maybe, find his skull. They say the skull goes last. The Kid used to have buck teeth that made him look like he was laughin’ when he wasn’t. And like as not, his buck teeth make his skull look like it’s laughin’ yet. It kind o’ gives you the creeps to think of him down there under the earth still laughin’.’”

“Romance weaves no magic glamour in this Hell’s Half-Acre where the Kid sleeps his last sleep,” Burns wrote. “From this coign of disillusion one sees his tragic life in stark perspective, crowded with outlawry, vendetta, hatreds, murders; twenty-one dead men like ghostly mile posts marking his brief journey of twenty-one years, a journey that through all the twists and turns of its crimson trail marched inevitably toward this lozenge of cactus-shadowed desolation.

Pecos flats, New Mexico“As you stand in a mood of reverie above the lonely spot, a vagrant wind whisks across the plain a tiny dust-devil that spins for a moment, madly, futilely, and is swallowed up in nothingness. This, in quick apocalypse, is the life of Billy the Kid—a little cyclone of deadliness whirling furiously, purposelessly, vainly, between two eternities. A little space of bare desert earth lost in the sagebrush is the guerdon of all his glory. For this, he lived and died. Here in his nameless grave on the dreary, wind-swept Pecos flats under sun and rain and drifting snows, the boy of the tiger heart rests at last in peace.”

Walter Noble Burns’s The Saga of Billy the Kid is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024