'The Two and Only Jane Russell'

June 21, 1921-February 28, 2011

Buxom, beautiful and talented--the first two attributes were readily observable, the third was revealed only later in her career--Jane Russell died at her home in Santa Monica, CA, of a respiratory-related illness on February 28. She was 89. She is survived by her three adopted children, Thomas Waterfield, Robert Waterfield and Tracy Foundas. If ever a woman was at risk of being reduced to her body parts, it was Russell, who was initially subject to a level of objectification as relentless as it was breathtaking.

She was born June 21, 1921 in Bemidji, Minnesota, the eldest child and only daughter among the five children of Roy William Russell and former actress Geraldine Jacobi. In 1930 family moved to California and settled in Burbank, where Russell's father worked as an office manager at a soap manufacturing plant.

Encouraged by her mother, Jane took piano lessons at an early age, and at Van Nuys High School began acting in stage productions. Becoming a designer was her first ambition, but after graduation, and following the sudden death of her father at age 46, she took work as a receptionist and also modeled for photographers. Again at her mother's urging, Jane studied drama and acting with Max Reinhardt's Theatrical Workshop and with Russian actress Maria Ouspenskaya, an Academy Award nominee for her 1936 role in Dodsworth, and fondly rememberd by horror film fans for her roles as a Gypsy fortune teller in The Wolf Man in 1941 and Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man in 1943. While studying acting, Russell obtained an agent, who began sending out publicity photographs to the Hollywood studios.

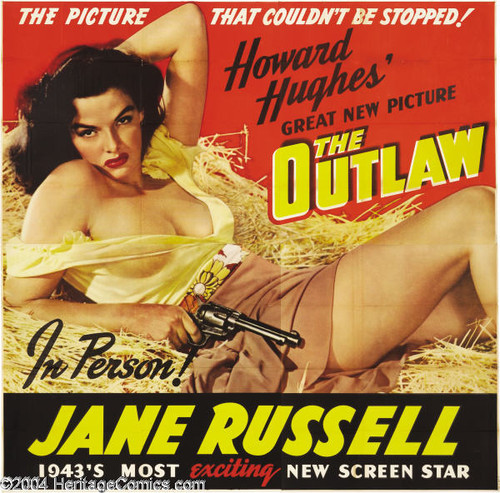

Selected scenes from The Outlaw, starring Jack Beutel and Jane RussellIn 1939 Howard Hughes was on a search for an unknown actress to star in a film he wanted to make based on the Billy the Kid story. When the word got out, his office was flooded with 8x10 glossies from actresses all over hoping to be a discovery on a par with another of Hughes's finds, Jean Harlow, fifteen years earlier. While wading through the mountain of photos, one caught Hughes's attention, that of a 19-year-old actress whose measurements were listed as 38-22-36. He ordered she be given a screen test.

"The actress was brown-eyed raven-haired Ernestine Jane Geraldine Russell, soon to be known as Jane Russell," wrote Peter Harry Brown and Pat H. Broeske in Howard Hughes: The Untold Story (Signet Books, 1997). "She was working as a part-time receptionist for a chiropodist when Hughes spotted the photo sent by her agent.

"Hughes was nowhere to be seen the day she was summoned to his headquarters at 7000 Romaine for a screen test in the basement. Against a makeshift barn setting, which included a haystack and pitchfork, Russell and other actors acted out a scene in which a half-Mexican girl named Rio is thrown to the ground by Billy the Kid after she's tried to kill him. Billy doesn't know it, but Rio hates him because he killed her brother. In the movie the scene would end with Billy raping Rio. 'Ye gods!' Russell is said to have exclaimed. But she wasn't at all flustered by her first experience in front of the cameras. 'Actually, it felt very natural,' she recalled.

"A few days later she was rewarded with good news. She had the role of Rio and a $0 a week contract. Also contracted for $50 a week was baby-faced Texan Jack Beutel, twenty-three, as Billy. Neither she nor Beutel could have known that The Outlaw was going to dominate their lives for the next decade."

Hughes had his engineers design a seamless underwire brassiere, a breakthrough in bra science to lift Russell's 38-D breasts, leaving no visible support lines to interrupt the under-blouse contour of her bosom. It was the first practical "lift and separate" push-up bra, but Russell later said she did not wear the uncomfortable contraption during filming. Instead she wore her own bras, adding a layer of tissue paper over the cups to eliminate unsightly support lines. Hughes, who took over the director's role from Howard Hawks, never knew the difference.

Theatrical poster for The Outlaw. In later films Howard Hughes would complain to his directors of photography, ‘We’re not getting enough production out of Jane’s breasts!’Completed in 1941, The Outlaw was unable to pass muster with the Hays Code. A legacy of Will H. Hays, one-time chairman of Republican Party and the first president of the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), "the code" was written to enforce morality in Hollywood movies. It stipulated, for example, that there be no nudity, no vulgar language, and that dramatizations of bad behavior from adultery to illegal drugs to any form of criminality had to be followed in the plot by an appropriate 'punishment'. There was no explicit rule against cleavage and jiggling, but The Outlaw obviously starred Russell's breasts, so the required certificate of approval was denied, effectively blocking the movie's release.

The censors remained unimpressed, even after 37 scenes of Russell were excised, and the film was pulled quickly from its limited release. In court, a judge said Russell's breasts "hung over the picture like a thunderstorm over a landscape. They were everywhere." Hughes sent Russell out on a publicity drive while planning his next move, and she became a favorite of the armed forces, voted the most popular female star in the country before the vast majority of people had ever seen her act. When The Outlaw finally secured a wider release in 1946, it was largely panned, but Russell--damned by one critic as "the queen of motionless pictures"--was established.

The problem was that she was established as simply a smoldering sexpot, and remained subject to wearisome tributes and jokes alike. A pair of embattled hills in Korea were named after her by U.S. troops. Bob Hope, her co-star in the successful 1948 comedy The Paleface, in which she played a spoofish version of Calamity Jane (she landed the role when Ginger Rogers was unavailable) introduced her as "the two and only Jane Russell," and quipped, "Culture is the ability to describe Jane Russell without moving your hands.” But Russell had talent and style enough to save her, wryness and coolness to burn, the wit to transcend all the nudging winks. She later starred twice with Robert Mitchum, in the excellent gangster drama His Kind of Woman and the sultry smuggling thriller Macao, and she re-teamed with Hope for the well-received sequel Son of Paleface.

‘Five Little Miles from San Berdoo,’ Robert Mitchum and Jane Russell in His Kind of Woman, directed by John Farrow (and an uncredited Richard Fleischer), executive produced by Howard Hughes. Also featuring Vincent Price, Tim Holt, Jim Backus and Raymond Burr.In her most famous film (and her personal favorite), Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, released in 1953, she gave a performance to justify the film critic David Thomson's admiring verdict decades later that "such droll eroticism is rare in Hollywood.”

In that film, Russell's character, Dorothy Shaw, is set up in direct opposition to the character of her best friend, Lorelei Lee, played by Marilyn Monroe. Where Lorelei is all baby voice and imploring, flashing eyes, desperate to marry a rich man, Dorothy is exactly the opposite. She is smart where Lorelei is brainless; grown-up where Lorelei is juvenile; wisecracking where Lorelei is breathy; straightforward where Lorelei is dissembling. She doesn't care for diamonds, but she does care for her own desires. The pair set sail from the U.S. to Paris and, early on, Russell performs one of the film's most memorable numbers, “Ain't There Anyone Here for Love?,” written specifically for her by Hoagy Carmichael. Singing in a gymnasium, she is joined by muscular actors playing the U.S. Olympic team, who form a distinctive--and distinctively subversive--Busby Berkeley chorus around her. "I like big muscles, and red corpuscles," she croons, eyes widening happily as an enormous bicep pops right in front of her eyes, a woman clearly in control of her own sexuality.

‘Ain’t There Anyone Here For Love?’ from Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, a song written by Hoagy Carmichael specifically for Jane Russell. (1953)Russell had success as a singer beginning in the late 1940s when, between film jobs, she was a frequent headliner at the Latin Quarter Club in Miami Beach. She often sang on Kay Kyser's popular radio broadcasts, and in the mid-1950s she toured in all-woman trios and quartets she organized herself, often alongside her friend Rhonda Fleming. In Son of Paleface she sang a trio of "Am I in Love?" with Hope and Roy Rogers, and the song was Oscar-nominated. Russell first appeared on the charts in 1950 when her duet of "Kisses and Tears" with Frank Sinatra from Double Dynamite was released as a single, and later the soundtrack for Gentlemen Prefer Blondes made it into the Top 10. She also recorded several albums of Christian music.

In 1954, Russell was again embroiled in MPAA squabbles over The French Line, a gaudy musical co-starring Gilbert Roland. It offered what was then called "vulgar" humor, with a bubble bath scene and "Lookin' for Trouble," a suggestive number Russell sang while dancing a hootchy-kootchy and wearing very little. For added audience incentive, The French Line was filmed in 3-D (“JR in 3D! Need we say more?” blared the promotions for the movie), which at least made for interesting views whenever Russell was in a shot. Condemned by the Catholic Legion of Decency, the movie ran an hour and forty-two minutes, but many theater owners snipped away as many as twelve minutes of footage fearing it might offend local morality. As a result, audiences were confused, and the box office suffered.

In 1955 she starred with Jeanne Crain but without Monroe in a mediocre sequel, Gentlemen Marry Brunettes, and in 1957 she starred in The Fuzzy Pink Nightgown, an amusing comedy with Keenan Wynn, about a kidnapped movie star falling in love with her kidnapper. Her movies, though, were not finding an audience, and Russell abandoned the movies for a return to nightclub singing. She served as TV spokeswoman for Lustre Creme shampoo, appeared in a few pictures in the 1960s, and made her last big-screen appearance in 1970 with a supporting role in Darker Than Amber, a now-forgotten but impressive action movie with Rod Taylor. Russell had a long run on Broadway, replacing Elaine Stritch in the Stephen Sondheim musical Company, and appeared in TV commercials in the 1970s for the Playtex Cross-Your-Heart Bra, describing its structural advantages for "full-figured gals."

Asked once why she quit, she replied: "Because I was getting old! You couldn't go on acting in those years if you were an actress over 30, honey." She continued to have an interesting, complicated life outside the industry, working tirelessly to promote adoption.

‘Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend,’ Jane Russell, Gentlemen Prefer BlondesWhen she was 19, unmarried and pregnant, young Russell underwent an illegal abortion, but it was clumsily performed, leaving her unable to bear children. With her first husband, Cleveland Rams star quarterback Bob Waterfield, she adopted and raised a daughter and two sons; but the wait and paperwork for their adoptions had taken several years, and after that, Russell spent much of her off-screen time working to make adoption easier. In 1952, she founded the World Adoption International Fund (WAIF), a group that eventually facilitated more than 50,000 adoptions. She testified before Congress in support of the Federal Orphan Adoption Bill in 1953, which allowed children fathered by American troops abroad to be adopted by American parents. In 1980, she was at the forefront of the lobbying effort for the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act, which provides reimbursement for eligible foster and adoptive parents, and financial assistance for the additional costs incurred with adopting handicapped children.

This mission won her the praise of feminist groups, but her anti-abortion stance didn't. Russell was a born-again Christian (at the height of her popularity she formed a weekly Bible study group called the Hollywood Christian Group, which met in her home, and later in life she appeared on the Praise the Lord program on the Trinity Broadcasting Network), a one-time alcoholic and a dedicated Republican who, in a late interview, would go so far as to describe herself as "a teetotal, mean-spirited, rightwing, narrow-minded, conservative Christian bigot, but not a racist.” (Her explanation that, in her estimation, bigotry "just means you don't have an open mind" softened the criticism aimed at her, but only a little.)

"Such views meant she could never be an obvious feminist icon offscreen," noted Kira Cochrane in the March 1 issue of The Guardian, "but in her best-known work, her most inspired turn, the film that will outlive us all, she is just that. She is one of those rare actors--objectified in their youth into almost-inevitable obsolescence--who managed to rise proudly, brilliantly, above all that, in one perfect, incendiary performance."

Jane Russell and Hoagy Carmichael, ‘My Resistance Is Low,’ from The Las Vegas Story, 1952, with Victor Mature and Vincent Price, directed by Robert Stevenson.Her first husband was her high school sweetheart, Bob Waterfield, who earned his fame as star quarterback of the Cleveland Rams. Waterfield threw two touchdown passes as Cleveland defeated the Washington Redskins 15-14 in the 1945 NFL Championship Game, later coached the team after its move to Los Angeles, and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1965. Russell and Waterfield were married for 25 years, before she divorced him in 1967. Her second husband was Roger Barrett, a stage actor who had appeared with Russell in a summer stock play. They were married only three months before he suffered a heart attack and died, reportedly in the throes of passion with Russell. Her third husband was a real estate broker, John Calvin Peoples, and again the marriage lasted 25 years, until his passing in 1999.

After her last husband's death, Russell found herself a little lonely and missing the limelight, so she organized a few friends as her backup band and began singing in a local Mexican restaurant. After a year and a half at the restaurant her un-advertised performances needed a larger venue, and the octagenarian star took her show to an airport hotel in Santa Maria, California. She performed twice monthly there, until shortly before her death.

Jane Russell performs Johnny Mercer-Harold Arlen’s ‘One for My Baby’ in the Josef von Sternberg/Nicholas Ray film noir, Macao (1952). Russell stars with Robert Mitchum; Howard Hughes was executive producer.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024