Leigh Hunt, or ‘Libertas,’ as Keats memorialized himMusical Memories

From The Autobiography of Leigh Hunt

Poet, essayist, critic, author, friend of Shelley, Byron, Thomas Moore and John Keats (he was the first to publish Keats’s La belle dame sans merci), James Henry Leigh Hunt (19 October 1784-28 August 1859) lived a life full of financial calamities and political controversies (he and his brother John served two years in prison for criticizing the Prince Regent in their radical journal Examiner, in an article headlined “The Prince on St. Patrick’s Day” in which Leigh called the late Prince of Wales an overweight, past-his-prime “Adonis”) but was tenacious and unflagging in introducing and encouraging various great literary minds of his day.. Keats immortalized him as “Libertas” in acknowledging Hunt’s influence on his own embrace of progressive politics. Moreover, as Keats’s Pulitzer Prize winning biographer W. Jackson Bate notes: “…the major influence on much of the poetry before the summer of 1816, and especially on the poetry of 1817, is still that of Hunt. … it was not just a literary influence in the ordinary sense of the term, but something psychologically more important... In at least one way it is analogous to the later influence of Milton and Shakespeare (and in a way that the influence of Spenser, for example, was not--however strong it might have been in other respects); for it had a great deal to do with encouraging him to write--with giving him an active model felt emphatically, with which for a while he was creatively identified. In this respect, the influence of Hunt was obviously valuable.”

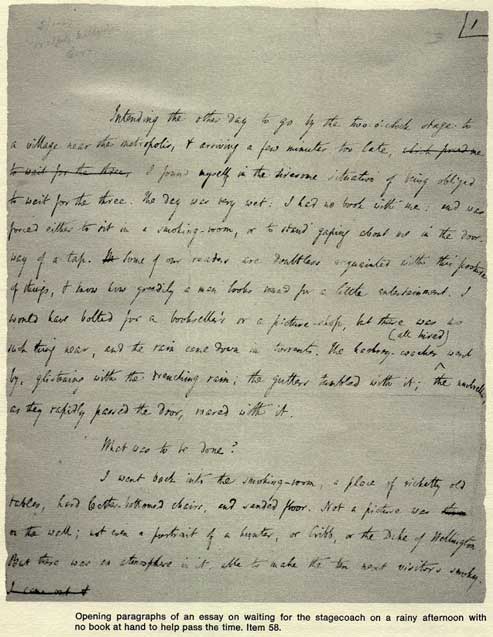

A page of Leigh Hunt’s 1824 essay ‘Intending The Other Day To Go By The Two O’clock Stage’Writing in the Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 28, Alexander Ireland offered the following appraisal of Hunt:

Leigh Hunt takes high rank as an essayist and critic. The spirit of his writings is eminently cheerful and humanizing. He is perhaps the best teacher in our literature of the contentment which flows from a recognition of everyday joys and blessings. A belief in all that is good and beautiful, and in the ultimate success of every true and honest endeavor, and a tender consideration for mistake and circumstance, are the pervading spirit of all his writings. Cheap and simple enjoyments, true taste leading to true economy, the companionship of books and the pleasures of friendly intercourse, were the constant themes of his pen. He knew much suffering, physical and mental, and experienced many cares and sorrows; but his cheerful courage, imperturbable sweetness of temper, and unfailing love and power of forgiveness never deserted him.

As a poet Leigh Hunt showed much tenderness, a delicate and vivid fancy, and an entire freedom from any morbid strain of introspection. His verses never lack the sense and expression of quick, keen delight in all things naturally and wholesomely delightful. But an occasional mannerism, bordering on affectation, detracts somewhat from the merits of his poetry. His narrative poems, such as “The Story of Kimini,” are, however, among the very best in the language. He is most successful in the heroic couplet. His exquisite little fable “Abou ben Adhem” has assured him a permanent place in the records of the English language.

“In appearance,' says his son, journalist Thornton Leigh Hunt, “Leigh Hunt was tall and straight as an arrow, and looked slenderer than he really was. His hair was black and shining, and slightly inclined to wave. His head was high, his forehead straight and white, under which beamed a pair of eyes, dark, brilliant, reflecting, gay, and kind, with a certain look of observant humor. His general complexion was dark. There was in his whole carriage and manner an extraordinary degree of life. His whole existence and habit of mind were essentially literary. He was a hard and conscientious worker, and most painstaking as regards accuracy. He would often spend hours in verifying some fact or event which he had only stated parenthetically. Few men were more attractive in society, whether in a large company or over the fireside. His manner was particularly animated, his conversation varied, ranging over a great field of subjects. There was a spontaneous courtesy in him that never failed, and a considerateness derived from a ceaseless kindness of heart that invariably fascinated.” Hawthorne and Emerson have left on record the delightful impression he made when they visited him. He led a singularly plain life. His customary drink was water, and his food of the plainest and simplest kind; bread alone was what he took for luncheon or supper.

In 1850 Hunt published his Autobiography. In her essay “A Portrait of Leigh Hunt” for the University of Iowa’s Books at Iowa 40 project in April 1984, Ann Blainey summarized The Autobiography of Leigh Hunt as “a charming book, courteous, mellowed but distant, the work of a seductive self-effacer.” From that work come the following reflections, in a chapter titled “Musical Memories” in which we learn that Benjamin Franklin, among his other endeavors, sought to teach Mr. Hunt’s mother how to play the guitar.

***

I

My grandfather, though intimate with Mr. Franklin, was secretly on the British side of the question when the American war broke out. He professed to be neutral, and to attend only to business; but his neutrality did not avail him. … My mother at that time was a brunette with fine eyes, a tall, ladylike person, and hair blacker than is seen of English growth. It was supposed that Anglo Americans already began to exhibit the influence of climate in their appearance. … My mother had no accomplishments but the two best of all, a love of nature and of books. Dr. Franklin offered to teach her the guitar; but she was too bashful to become his pupil. She regretted this afterwards, partly, no doubt, for having lost so illustrious a master. Her first child, who died, was named after him. I know not whether the anecdote is new; but I have heard that when Dr. Franklin invented the Harmonica [note: the “musical glasses” encased in a machine.], he concealed it from his wife till the instrument was fit to play; and then woke her with it one night when she took it for the music of the angels.

… My mother, though fond of music, and a gentle singer in her way, had missed the advantage of a musical education, partly from her coming of a half-Quaker stock, partly (as I have said before) from her having been too diffident to avail herself of the kindness of Dr. Franklin, who offered to teach her the guitar.

‘The Lass of Richmond Hill,’ music by James Hook, lyrics by Leonard McNally, published circa 1790.The reigning English composer at that time was “Mr. Hook” [note: James Hook, 1746-1827], as he was styled at the head of his songs. He…had a real, though small vein of genius, which was none the better for its being called upon to flow profusely for Ranelagh and Vauxhall. He was the composer of “The Lass of Richmond Hill” (an allusion to a penchant of George IV), an of another popular song more lately remembered, “‘Twas within a mile of Edinborough town.” The songs of that day abounded in Strephons and Delias, and the music partook of the gentle inspiration. The association of early ideas with that kind of commonplace has given me more than a toleration for it. I find something even touching in the endeavors of an innocent set of ladies and gentlemen, my fathers and mothers, to identify themselves with shepherds and shepherdesses in the most impossible hats and crooks, … The feeling was true, though the expression was sophisticate and a fashion; and they who cannot see the feeling for the mode, do the very thing which they thing they scorn; that is, sacrifice the greater consideration for the less.

But Hook was not the only, far less the most fashionable composer. There were (if not all personally, yet popularly contemporaneous) Mr. Lampe, Mr. Oswald, Dr. Boyce, Linley, Jackson, Shield, and Storace, with Paesiello, Sacchini, and others at the King’s Theatre, whose delightful airs wandered into the streets out of the English opera that borrowed them, and became confounded with English property. I have often, in the course of my life, heard “Whither, my love?” and “For tenderness formed” boasted of as specimens of English melody. For many years I took them for such myself, in common with the rest of our family, with whom they were great favorites. The first, which Stephen Storace adapted to some words in The Haunted Tower in the air of La Rachelina in Paesiello’s opera La Molinara. The second, which was put by General Burgoyne to a song in his comedy of The Heiress (1786) is “Io sono Lindoro” in the same enchanting composer’s Barber of Seville. [Note: The composers worth identifying are: William Boyer (1710-1779); Giovanni Paesiello (1746-1816), and Antonio Sacchini (1734-1786).] … Every burlesque or buffo song, of any pretension, was pretty sure to be Italian. When Edwin, Fawcett, and others were rattling away in the happy comic songs of O’Keefe, with his triple rhymes and illustrative jargon, the audience little suspected that they were listening to some of the finest animal spirits of the south--to Piccini [Note: Nicolo Piccini, 1728-1800], Paesiello, and Cimarosa [Note: Opera composer (1749-1801) who died after imprisonment for his part in the attempted liberation of Italy from Bonaparte’s troops.].

‘I am heretic enough to believe that Arne was a real musical genius’: ‘When daisies a pied’ by Shakespeare, set to music by Thomas Arne. Yvonne Fuller, soprano; Dorothy Marshall, organ.… I must own that I am heretic enough (if present fashion is orthodoxy) to believe that Arne [Note: Thomas Arne, 1710-1778] was a real musical genius, of a very pure, albeit not of the very first water. He has set, indeed, two songs of Shakespeare’s (the Cuckoo song and “Where the bee sucks”) in a spirit of perfect analogy to the words as well as the liveliest musical invention; and his air of “Water parted” in Artaxerxes winds about the feelings with an earnest and graceful tenderness of regret, worthy in the highest degree of the affecting beauty of the sentiment.

… The other day I found two songs of that period on Robinson’s music stall in Wardour Street, one of Mr. Hook entitled “Alone, by the light of the moon”; the other, a song with a French burden, called “Dans autre lit,” an innocent production notwithstanding its title. They were the only songs I recollect singing when a child, and I looked on them with the accumulated tenderness of sixty-three years of age. I do not remember to have set eyes on them in the interval. What a difference between the little smooth-faced boy at his mother’s knee, encouraged to lift up his voice at the pianoforte, and the battered, gray-headed senior, looking again for the first time on what he had sung at the distance of half a century! Life often seems a dream; but there are occasions when the sudden reappearance of early objects, by the intensity of their presence, not only renders the interval less present to the consciousness than a very dream, but makes the portion of life which preceded it seem to have been the most real of all things, and our only undreaming time.

II

It was very pleasant to see Lord Byron and Moore [Note: Thomas Moore, 1779-1852, Irish poet and wit, biographer of Byron, and arranger of the ballads of his native land] together. They harmonized admirably: though their knowledge of one another began in talking of a duel. … Moore’s acquaintance with myself (as far as concerned correspondence by letter) originated in the mention of him in the “Feast of the Poets” [Note: poem by Hunt, 1811]. He subsequently wrote an opera called The Blue Stocking (1811), respecting which he sent me a letter at once deprecating and warranting objection to it. I was then editor of the Examiner: I did object to it, though with all acknowledgement of his genius.

Shirley Temple, as Little Vergie, serenades her father (John Boles) with Thomas Moore’s 1808 song ‘Believe Me, If All Those Endearing Young Charms’ in the 1935 film The Littlest Rebel.Moore…sang and played with great taste on the pianoforte, as might be supposed from his musical compositions. His voice, which was a little hoarse in speaking (at least I used to think so), softened into a breath, like that of the flute, when singing.

•

[At Pisa] our manner of life was this. Lord Byron, who used to sit up at night writing Don Juan (which he did under the influence of gin and water), rose late in the morning. He breakfasted; read; lounged about, singing an air, generally out of Rossini; then took a bath, and was well dressed; and coming downstairs was heard, still singing, in the back of the house. The servants, at the same time, brought out two or three chairs. My study, a little room in a corner, with an orange tree at the window, looked upon this courtyard. I was generally at my writing when he came down, and either acknowledged his presence by getting up and saying something from the window, or he called out, “Leontius!” (a name which Shelley had pleasantly converted that of “Leigh Hunt”) and came up to the window with some jest or other challenge to conversation.

•

[In Genoa] one night I went to the opera, which was indifferent enough, but I understand it is a good deal better sometimes. The favorite composer here and all over Italy is Rossini, a truly national genius, full of the finest animal spirits, yet capable of the noblest gravity. My northern faculties were scandalized at seeing men in the pit with fans! Effeminancy is not always incompatible with courage, but it is a very dangerous step towards it; and I wondered what Doria would have said had he seen a captain of one of his galleys indulging his cheeks in this manner. Yet perhaps they did so in his own times.

It was about this time [1835] that I projected a poem of a very different sort, which was to be called “A Day with the Reader.”

I proposed to invite the reader to breakfast, dine, and sup with me, partly at home and partly at a country inn, in order to vary the circumstances. It was to be written both gravely and gaily, in an exalted or in a lowly strain, according to the topics of which it treated. The fragment of “Paganini” was part of the exordium--

So play’d of late to every passing thought

With finest change (might I but half as well

So write!) The pale magician of the bow, etc.

Alexander Markov performs Paganini’s Caprice no. 5I wished to write in the same manner because Paganini with his violin could move both the tears and the laughter of his audience, and (as I have described him doing in the verses) would now give you the notes of birds in the trees, and even hens feeling in a farmyard (which was a corner into which I meant to take my companion), and now melt you into grief and pity, or mystify you with witchcraft, or put you into a state of lofty triumph like a conqueror. That phrase of “smiting” the chords--

He smote: and clinging to the serious chords

With godlike ravishment, etc.--was no classical commonplace; nor, in respect to impression on the mind, was it exaggeration to say that from a single chord he would fetch out

The voice of quires, and weight

Of the built organ.Paganini, the first time I saw and heard him, and the first moment he struck a note, seemed literally to strike it; to give it a blow. The house was so crammed that, being among the squeezers in “standing room” at the side of the pit, I happened to catch the first sight of his face through the arm akimbo of a man who was perched up before me, which made a kind of frame for it; and there, on the stage, in that frame, as through a perspective glass, were the face, bust, and raised hand of the wonderful musician, with his instrument at his chin, just going to commence, and looking exactly as I have described him--

His hand,

Loading the air with dumb expectancy,

Suspended, ere it fell, a nation’s breath,

He smote;…

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024