Young Len Slye, on his way to becoming Roy Rogers, with his trusty OM-45 Deluxe Martin guitar. He purchased the used instrument for $30 (when new in 1930 it sold for $225) at a California pawn shop in 1933 and it became identified with him as his film and recording careers took off. In 2009 Christie’s auction house in New York sold the instrument for $460,000. As it happens, a check of the instrument’s serial number proved it to be the very first OM-45 Deluxe model produced.A Real Singing Cowboy

Happy Trails to Roy Rogers, Born 100 Years Ago This Month

November 5 marked the 100th anniversary of the birth of Roy Rogers, King of the Cowboys. Today's younger generation likely know Roy from the Roy Rogers Restaurants chain, if they know him at all. Baby boomers embraced him as a cultural hero during the 1951-1957 run of his 100-episode western TV series, The Roy Rogers Show featuring Roy as a ranch owner, his wife Dale Evans as the proprietor of the Eureka Café in fictional Mineral City and Roy's Sons of the Pioneers buddy Pat Brady as his wacky sidekick and Dale's cook. He was an even bigger hero to another, earlier generation as a genial, morally upright singing cowboy nabbing the bad guys and serenading the ladies and lads in an unbelievable run of popular movie westerns that began in 1938 (when the man born Leonard Slye was rechristened Roy Rogers and signed to play the lead in Under Western Stars). For 15 consecutive years, from 1939 to 1954, he not only ranked in the Top 10 of the Motion Picture Herald's Top Ten Money-Making Western Stars, he was Number One from 1943 to 1954. In 1945 and '46 he was in the Top Ten Money Makers Poll of all films. He was a merchandising behemoth, too: as his Wikipedia entry notes: "There were Roy Rogers action figures, cowboy adventure novels, and playsets, as well as a comic strip, a long-lived Dell Comics comic book series (Roy Rogers Comics) written by Gaylord Du Bois, and a variety of marketing successes. Roy Rogers was second only to Walt Disney in the amount of items featuring his name."

A black and white still mirroring the lobby card from Gene Autry's The Big Show (1936). From left are Sons of the Pioneers Karl Farr (guitar), Bob Nolan (bass), Tim Spencer, Hugh Farr (fiddle), and on the far right is a young Len Slye (who became 'Dick Weston' and was a year or so away from becoming 'Roy Rogers'). In the mid 1930s, the Sons of the Pioneers worked in a couple of the early Autry westerns as well as a pair of the Dick Foran horse operas for Warners. Their next stop was at Columbia Pictures with Charles Starrett.Although Roy and Dale's theme song, "Happy Trails," was and remains a tune indelibly associated with the 1950s, by the time Roy became as big a star on TV as he had been on the silver screen he had also pretty much left behind a singing career that itself approached legendary proportions--or rather was legendary for the imprint it made on western music during the years he led the quintessential, still-unmatched western harmony group, Sons of the Pioneers, whose members included the greatest of all western songwriters, Bob Nolan, the poet laureate of the western song.

The King of the Cowboys was actually born in a city, in Cincinnati, Ohio, on November 5, 1911, birth name Leonard Slye, son of Mattie and Andy Slye. Years later, the building where Roy was born was torn down to make way for Riverfront Stadium (now Cinergy Field), the home of the Cincinnati Reds baseball team. Roy liked to joke that he was born on the spot where second base is now located. A few months after Leonard's birth, Andy Slye moved his family to Portsmouth, Ohio (a hundred miles east of Cincinnati), where they lived on the houseboat that he and Roy's uncle built. When Roy was seven years old his father decided it was time they settled on solid ground, so he bought a small farm in nearby Duck Run. Living on a farm meant long hours and hard work, but no matter how hard they worked the land there was little money to be made. Roy often said that about all they could raise on their farm were rocks.

Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers, ‘Dust,’ from Roy’s first starring vehicle, 1938’s Under Western Stars, in a role originally written for Gene Autry, who backed out of the production. Autry co-wrote ‘Dust,’ which was nominated for an Oscar.Mattie Slye suffered from lameness as a result of the polio she had contracted as a child, and Roy always marveled at the way she was able to raise four active children (Roy and his sisters, Mary, Cleda, and Kathleen) despite her disability. Still, farm life agreed with Roy, who often rode to school on Babe, the old, sulky racehorse his father had bought for him. According to Roy, "We lived so far out in the country, they had to pipe sunlight to us." Living on the farm meant they had to make their own entertainment, since radio was in its earliest days and television was far in the future. On Saturday nights the Slye family often invited some of their neighbors over for a square dance, during which Roy would sing and play the mandolin. Before long he became skilled at calling square dances, and throughout the years he always enjoyed finding opportunities to showcase this talent in his films and television appearances.

It was also while he was growing up on the farm in Duck Run that Roy learned to yodel. Andy Slye had brought home a cylinder player (the predecessor to the phonograph) along with some cylinders, including one by a Swiss yodeler. Roy played that cylinder again and again and soon began developing his own yodeling style. Before long, Roy and his mother worked out a way of communicating with each other by using different types of yodels. Mattie would use one type of yodel to let Roy know that it was time for lunch, another to warn that a storm was brewing, and still another to call him in at the end of the day. Roy would then relay that message to his sisters by yodeling across the fields to them.

Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers, ‘Sweet Betsy From Pike,’ from the 1944 film Song of NevadaWith his family struggling to make ends meet, Roy dropped out of high school after his second year and took a job with his father at a Cincinnati shoe factory. Hating the dull, dreary factory work, father and son both quit and made a joint decision to move the family to Lawndale, California, near Los Angeles, where Roy's older sister Mary was living with her husband. After four months in California the Slyes returned to Ohio, but relocated to California permanently after winter had passed. In those Depression years work was as hard to find in the Golden State as it was in Ohio, but Roy landed a series of short-term jobs that helped keep a roof over the family's head, including driving a gravel truck on a highway construction crew until the truck's owner went bankrupt. In the spring of 1931 Roy ventured to Tulare (located in central California's farm belt), where he picked peaches for Del Monte and lived in the same labor camps John Steinbeck wrote about so powerfully in The Grapes Of Wrath.

After returning from Tulare, Roy happened to be playing his guitar and singing at his sister Mary's house when she suggested that he try out for the Midnight Frolic radio program, which featured amateur talent and was broadcast on KMCS in nearby Inglewood. Although Roy was reluctant, Mary finally talked her brother into going on the program. A few nights later, wearing a Western shirt his sister had made for him, Roy overcame his innate shyness and appeared on the program, where he sang, yodeled, and played the guitar. Years later, Roy said that he was so nervous when he came to the microphone that afterward he never could remember what songs he sang that night. Nevertheless, he made an impression, as he learned a few days later upon receiving an invitation to join a local country music group called The Rocky Mountaineers. Despite his shyness Roy knew to seize any opportunity that came his way, so he accepted the group's offer and became a member of the band in August of 1931. Soon he urged the group to let him find another vocalist, so they could harmonize together. Responding to an ad in the Los Angeles Examiner seeking a "yodeler," Bob Nolan showed up for his audition carrying his shoes in his hand. Bob had spent the summer working as a lifeguard at Venice Beach, and the long walk from the old red car trolley line to the house where The Rocky Mountaineers were rehearsing had caused his new shoes to raise blisters on his feet. Shoeless or no, Bob Nolan was a singular talent. As soon as Roy heard Bob yodel, his eyes lit up, and Bob knew he had the job. Before long, Bob's friend Bill "Slumber" Nichols joined the group, and they began singing together as a trio.

Production still from Song of Arizona, 1946: (from left) Tim Spencer, Bob Nolan, Roy Rogers, Ken Carson and Karl Farr (Photo: The Theresa Sevigny Scott Collection)Bob Nolan stayed with The Rocky Mountaineers for about a year before deciding the group really didn't have a future. Roy placed another newspaper ad, and Tim Spencer became the newest member of the group. In September 1932 Roy, Tim, and Slumber left The Rocky Mountaineers and worked briefly with The International Cowboys. In June 1933 Roy and Tim joined a new group called The O-Bar-O Cowboys and embarked on what turned out to be a disastrous tour of the Southwest. The Depression had hit rock bottom and entertainment was something most people simply couldn't afford. The boys barely made enough money to pay for gasoline as they drove throughout Arizona and New Mexico in the heat of summer in the days before air conditioning. Roy recalled, "We starved to death on that trip. We ate jack rabbits, we ate anything we could get to eat." While in Roswell, New Mexico, the group was given air time on the local radio station so that they could promote their appearance in town. Each of the boys talked about how homesick he was and mentioned his favorite foods in hopes someone might take pity on them. Roy mentioned how much he missed his mom's lemon pies, and a short time later a call came in to the station saying that if he would sing "The Swiss Yodel" the caller would bake him a pie. That evening there was a knock on the cabin door at the motor court where the boys were staying. When the door was opened, there stood Arline Wilkins and her mother, each with a freshly baked lemon pie. After Roy's return to Los Angeles, he and Arline began corresponding, and in 1936 they were married.

In September 1933 The O-Bar-O Cowboys straggled back to Los Angeles and the fellows went their separate ways. Roy was able to land a job singing with Jack And His Texas Outlaws on radio station KFWB. Still, the desire to be part of a good harmony group wouldn't leave him. Roy always loved harmony singing, and even after achieving success as a solo performer, he preferred singing harmony to singing solo. He contacted Tim Spencer and talked him into giving it another try and said he thought Bob Nolan should be the third member of the trio. Roy and Tim drove out to the Bel Air Country Club where Bob was working as a golf caddy. (Somehow or other, even in the midst of the Depression, Roy always managed to have "wheels.") Although Bob was somewhat reluctant, he agreed to join with them and see if they could make a go of it. The three fellows moved into a boarding house in Hollywood (that had once been owned by Tom Mix), and they began rehearsing. The boys decided to put the emphasis on Western music and call themselves The Pioneer Trio. Day after day and hour after hour they rehearsed until someone's voice gave out. Throughout this time Roy continued singing with The Texas Outlaws so they could pay their rent. After weeks of constant rehearsing, the trio finally felt they were ready to be heard.

Roy Rogers, Bob Nolan and the Sons of the Pioneers sing the beautiful Jack Elliott ballad ‘Lights of Old Santa Fe,’ title track of the 1944 movie.The boys were able to get an audition at KFWB, and many years later Bob Nolan recalled that day. He and Roy and Tim were confident they'd developed a good vocal blend, had some fine original songs, and had come up with a unique trio yodel. While they stood on stage singing, Jerry King, the station's general manager, along with staff announcer Harry Hall, listened to them from the control booth. After a couple of tunes The Pioneer Trio went into Bob's song "Way Out There," which featured their distinctive trio yodel. As soon as they began the yodel, Jerry King got up and left the booth. Bob recalled, "Our hearts fell to our feet." It seemed as if the endless weeks of rehearsing, developing a new sound, writing songs, and building a large library of musical material had all been for nothing. When a smiling Harry Hall came over to the boys, they asked why he was so happy when the station manager had just walked out on them. Their despair turned to elation when Hall told them that as soon as Jerry King had heard their trio yodel he had decided to hire the group.

The Pioneer Trio started out on the Jack And His Texas Outlaws radio program, where their fine harmonies soon began attracting a trove of fan mail along with good newspaper reviews. The boys had worked up a particularly fine arrangement of "The Last Round-Up," which caught the attention of Bernie Milligan, the radio columnist for the Los Angeles Examiner. "The Last Round-Up" had become the year's biggest hit song and was being performed by just about everyone on radio. Milligan said The Pioneer Trio's arrangement was the best of all the versions he'd heard. His review and their growing fan mail didn't go unnoticed by Jerry King. Roy always smiled when he recalled, "The station put us on staff at $35 a week . . . and I mean every week." The Pioneers were given a program of their own where they began using Bob Nolan's "Tumbling Tumbleweeds" as their theme song. Meanwhile, Bob continued writing more fine Western songs, while Tim Spencer, inspired by Bob's efforts, began trying his hand at songwriting. The Pioneer Trio's harmonies and the original songs of Nolan and Spencer's became the very foundation of Western music. Always determined to improve their sound, the fellows soon decided they needed a good instrumentalist and added superb fiddler Hugh Farr to the group. One day Harry Hall caught the boys off guard by introducing them as The Sons of the Pioneers. After their broadcast they asked why he'd changed their introduction. Hall said he thought they were too young to be pioneers, but that they certainly could be Sons of the Pioneers. Since Hugh Farr was now a permanent member of the group, the fellows decided Hall was right, and ever since that day they've been known as The Sons of the Pioneers. Hugh Farr began encouraging the boys to bring his guitarist brother Karl into the group. Karl joined the Pioneers early in 1935, and, according to Roy, that was the turning point for the group as they became as strong instrumentally as they were vocally. Jerry King had heard something unique in the Pioneers' sound and had given them their first job. Now he was about to do something that would spread their popularity nationwide.

Lobby card from the Trucolor Under California Stars (Republic, 1948). Pat Brady (bass), Hugh Farr (fiddle), Doye O’Dell, Roy Rogers (at microphone), Lloyd Perryman, Bob Nolan, Karl Farr (guitar). This Roy Rogers film was among the 1947-48 releases that marked the end of the trail for Nolan and the Sons of the Pioneers at Republic Pictures and in series westerns. Their last B-western was Nighttime In Nevada (Republic, 1948) another Trucolor western starring Rogers that was released in September 1948. The group, sans Nolan, did appear in a few other films such as the cavalry regimental singers in Rio Grande (1950), which starred John Wayne and was directed by John Ford.The early 1930s saw radio blossom as hundreds of stations went on the air throughout the country. While stations in major cities like New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles had large pools of talent to draw from, stations in smaller cities and towns didn't. This created a need for additional sources of programming and led to the birth of the radio transcription business. Transcription companies produced large libraries of music that was pressed on records and licensed to radio stations. The transcription companies recorded many of the biggest names in music as well as some of the newer artists. In the summer of 1934 Jerry King began Standard Radio, his own transcription company, and the first artists he recorded were The Sons of the Pioneers. Up until that point the Pioneers had been heard only in the Southern California area through their radio broadcasts and personal appearances. All this changed when their transcriptions began being played on hundreds of radio stations throughout the United States and Canada.

Meanwhile, radio work had led to the Pioneers' first film appearance, in the Warner Bros. short Radio Scout, starring Swedish comedian El Brendel. A few months later the Pioneers made their feature film debut, in The Old Homestead, which featured Mary Carlisle. These films were soon followed by their appearances in two Westerns starring Charles Starrett (Gallant Defender and The Mysterious Avenger), two with Dick Foran (Song Of The Saddle and California Mail), and an appearance in the Bing Crosby film Rhythm On The Range, where they joined Bing in singing "I'm An Old Cowhand (From The Rio Grande)." In July 1936 the Pioneers left KFWB and traveled to Dallas to appear at the Texas Centennial. While performing there they appeared in Gene Autry's film The Big Show, which was partially filmed on location at the Centennial. Interestingly, one of the visitors who saw The Sons Of The Pioneers perform at the Texas Centennial was a young singer named Dale Evans.

‘Lonely but free I’ll be found/drifting along with the tumbling tumbleweeds’: a Bob Nolan classic as introduced in 1934 by Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers. Nolan composed the song while he was working as a caddy and living in Los Angeles. Originally titled ‘Tumbling Tumble Leaves,’ the song was reworked into ‘Tumbling Tumbleweeds’ and into fame with the 1935 Gene Autry film of the same name.Back in Los Angeles the Pioneers continued radio work on KHJ along with more film work and recordings for Decca and OKeh. The enormous success of Gene Autry's films had caused just about every movie studio to jump on the singing cowboy bandwagon, and Columbia Pictures signed The Sons of the Pioneers to appear in Charles Starrett's series of Westerns. In the meantime Gene Autry had grown unhappy with his contract with Republic Pictures and was threatening that he might not report for the start of his next film. Republic decided to prepare themselves just in case he carried through on this. One day while Roy (who was still known as Len Slye) was in a hat store in Glendale, he heard someone say that Republic was holding auditions for a singing cowboy the following day.

"I saddled my guitar the next morning and went out there, but I couldn't get in because I didn't have an appointment. So I waited around until the extras began coming back from lunch, and I got on the opposite side of the crowd of people and came in with them. I'd just gotten inside the door when a hand fell on my shoulder. It was Sol Siegel, the head producer of Western pictures." Siegel, who remembered Roy from the work he and the Pioneers had done in two of Gene Autry's films, asked what he was doing there. When Roy said he'd heard they were looking for another singing cowboy, Siegel asked if he'd brought his guitar with him. Roy said it was in his car, but that he'd run back and get it. By the time he got back to the producer's office he was out of breath and couldn't sing. Siegel told Roy to rest for a minute and then he'd listen to him. The wait must have been worthwhile, because on Wednesday, October 13, 1937, Republic Pictures signed Len Slye to a seven-year contract. Republic put him to work in the Three Mesquiteers film Wild Horse Rodeo in which, billed as Dick Weston, he sang one song. Things were quiet for a few months until Gene Autry failed to report for the start of his next film. By then the studio was prepared, and they put Len Slye, who had been renamed Roy Rogers, into the lead role in Under Western Stars, the film that had been scheduled for Autry. When Under Western Stars was released in April 1938, it became an immediate hit, and it made a star of Roy Rogers. Gene Autry and the studio soon resolved their differences, but in the meantime Republic Pictures had launched Roy Rogers' career.

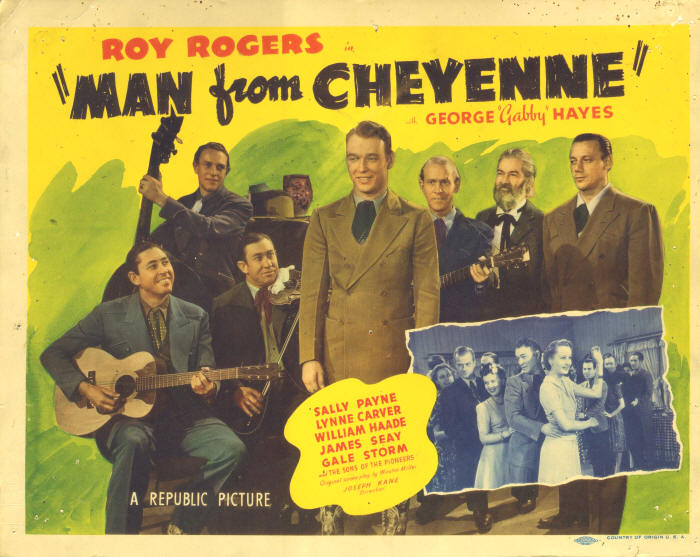

The title lobby card for Man From Cheyenne (Republic, 1942). Behind Roy Rogers from, from left, are Karl Farr (guitar), Lloyd Perryman (bass fiddle), Hugh Farr (fiddle), Tim Spencer (guitar), George 'Gabby' Hayes and Bob Nolan.Before filming began on Under Western Stars, several of the stables that provided horses to Republic brought their best lead horses to the studio so Roy could select a mount. As Roy recalled it, the third horse he got on was a beautiful golden palomino who handled smoothly and reacted quickly to whatever he asked it to do: "He could turn on a dime and give you some change." Smiley Burnette, who played Roy's sidekick in his first two films, was watching and mentioned how quick on the trigger this horse was. Roy agreed and decided that Trigger was the perfect name for the horse with which he would become synonymous. After the success of Under Western Stars, Republic starred Roy in a series of historical Westerns--Rough Riders Roundup, Days Of Jesse James, Frontier Pony Express and Young Buffalo Bill--as he quickly established himself as a major Western star. Early in 1940 Roy received excellent reviews for his role as Claire Trevor's younger brother in the film The Dark Command, which also starred John Wayne and Walter Pidgeon.

From 1938 to 1954 Roy recorded and performed as a solo artist, with the Sons of the Pioneers and with his wife Dale Evans, extensively on radio, and for labels including OKeh and RCA. In any configuration, Roy sang good songs and used his warm, clear tenor effectively both in enhancing the mystical quality of the existential loners in Bob Nolan's songs and the mysterious, haunting beauty of the natural world Nolan captured better than any other western writer--pretty much better than any songwriter, if the truth be told--and in bringing a lively, sunny spirit to upbeat numbers such as Cole Porter's "Don't Fence Me In," Al Dexter's honky tonk classic "Pistol Packin' Mama," and Frank Loesser and Joseph Lilley's "Jingle, Jangle, Jingle." His repertoire included songs by A.P. Carter ("I'm Thinking Tonight of My Blue Eyes"); Gordon Jenkins, one of Sinatra's favored arrangers ("San Fernando Valley"); Thomas A. Dorsey, the father of gospel music ("Peace In the Valley"); Oscar Hammerstein and Jerome Kern ("Ol' Man River"); Johnny Mercer ("I'm an Old Cowhand [From the Rio Grande]"), and other familiar names from the pop and country worlds. He and Dale both were accomplished songwriters as well, with Dale having the distinction of writing the couple’s signature song, "Happy Trails."

Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers, ‘I’m a Happy Man in My Levi Britches,’ written by Tim Spencer for the 1944 film, Lights of Old Santa Fe. The Sons of the Pioneers riding with Roy are: Bob Nolan, Tim Spencer, Ken Carson, Shug Fisher, Hugh and Karl Farr.But it was with the Sons of the Pioneers that Roy made his lasting mark as a musical artist. Both Roy and group member Tim Spencer contributed solid songs to the Sons' catalogue, but Bob Nolan's monuments--"Cool Water," "Tumbling Tumbleweeds," "A Cowboy Has To Sing," "Way Out There," "Blue Prairie" (a co-write with Tim Spencer)--along with lesser known gems from the movie years elevated the western song to high art, with a sophistication of lyrics and composition virtually unprecedented in music nominally regarded (and dismissed) as country. The great western concept albums Marty Robbins and Johnny Cash produced in the '60s would not be unthinkable without Bob Nolan, Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers, but they might have been very different absent the Bob Nolan poetry that was in place before Robbins and Cash arrived on the scene.

Today's leading western music artist, Michael Martin Murphey, speaking to this publication in an August 2011 cover story, pinpointed what made Nolan's songs unique, unforgettable and, indeed, important.

"Number one, he was a master of the jazz chord changes of his day and could get way beyond the simple three-chord cowboy song," Murphey observed. "And he used that to evoke the landscape and the lonesome, vast, wide-open nature of the landscape. Benny Goodman wasn't about that. The Cotton Club wasn't about that. But Nolan took the Cotton Club chords and realized that you could do it a little bit different way, put it together in a different way so that you could evoke a whole other world with those same chords. That was his genius, to take American jazz and turn it into a western landscape. Even in the sound of it. You get the pace of a horse riding along, loping along, in the song, and then you start adding chords to it that are very strange and unusual, oddball, and it's kind of like being in Monument Valley. You're hearing a musical landscape that's very unusual. His compositions, musically, were his main genius."

Roy Rogers and the Sons of the Pioneers’ original 1936 recording of Bob Nolan’s ‘Cool Water’A resurgence in his music career in the '70s found Roy having lost nothing in being off record for nearly a decade. He had a string of fine country and gospel albums for 20th Century and Word, and in 1991 found himself with a Top 20 country album in RCA's Roy Rogers Tribute, a splendid, high-spirited affair featuring Roy backed by all-star musicians from the country, bluegrass and pop worlds, including Brent Rowan, Randy Goodrum, Steve Gibson, Paul Franklin, Joey Miskulin, Mitch Humphries, Henry Strzelecki, Jerry Carrigan, Paul Leim, guitar titans Al Casey and Tommy Tedesco, Charlie McCoy, Hargus "Pig" Robbins, Pete Drake, Ray Edenton, Roy Huskey, Buddy Harman and Glen Hardin, among others. The tribute album also yielded Roy's first hit single since 1980's Sons of the Pioneers reunion ("Ride Concrete Cowboy, Ride") in a duet with young Roy lookalike-new country heartthrob Clint Black on "Hold On Partner."

Roy's movies are straightforward good guy vs. bad guy fare lacking the emotional complexities in plot and character that would mark the towering '50s westerns of John Ford and Budd Boetticher and TV series such as Steve McQueen's Wanted: Dead or Alive, or Gunsmoke as it developed. Even so, the innocence of those films, aided by the stars' genuinely winning performances, along with some very good musical interludes, make them fascinating touchstones in the evolution of movie westerns and western movie music.

The essential overview of Roy Rogers' musical career is provided by the Rhino box set issued in 1999, Happy Trails: The Roy Rogers Collection (from which parts of this tribute are drawn by way of Laurence Zwisohn's liner booklet essay, "Happy Trails: The Life of Roy Rogers"). In addition to various label recordings, the four-CD set includes the early radio transcriptions that vaulted the Sons of the Pioneers to fame, as well as well as solo Roy and solo Dale releases, a taste of Roy’s 1970s work and a few cuts from the 1991 Roy Rogers Tribute album. Now out of print, it is available from several Amazon dealers. Many Sons of the Pioneers collections are in print (and there were several Sons lineups, including one, after Nolan left the group, featuring Ken Curtis, a member of John Ford’s troupe and, post-Sons, a TV star in the role of Festus Hagen on Gunsmoke) with one of the sharpest overviews being the 16-track Country Music Hall of Fame collection released by MCA Nashville in 1991 and available at Amazon for less than $10 as this is written.

Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, ‘Happy Trails’As anyone who had the good fortune to meet Roy Rogers knows, he was a genuinely humble man who appreciated the public's affection for him and his work. He really was the man he appeared to be in all those movies and TV shows, as positive and life affirming as the music he sang. What Laurence Zwisohn observes at the end of his Rogers essay is verifiable truth, to wit: "(Roy) just wouldn't have known how to be anything else."

Happy trails, until we meet again.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024