Champagne Charlie, gentlemen of the road (from left) Peer Bout, Geert de Heer, Peter Lenselink, Sjef Hermans, Gait Klein Kromholf, Theo de Koning. (Photo: Hans de Graaf)TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview

Champagne Charlie Celebrates ‘Gentlemen Of the Road’

A new album from the Dutch string band casts a fresh light on American hobo life and culture

By David McGee

This publication has a strong relationship with the Dutch string band Champagne Charlie, dating back to our in-depth feature--the only one in any American-based publication--on CC’s Waitin’ On Roosevelt album, a project that lead singer/songwriter Sjef Hermans described as beginning as “a soundtrack of the Depression.” But in its finished form, Waitin’ On Roosevelt’s Depression-era songs had an unsettling relevance to our own times and to the right-wing attacks on President Obama’s policies--contrary to what Bob Wills sang, time does not change everything.

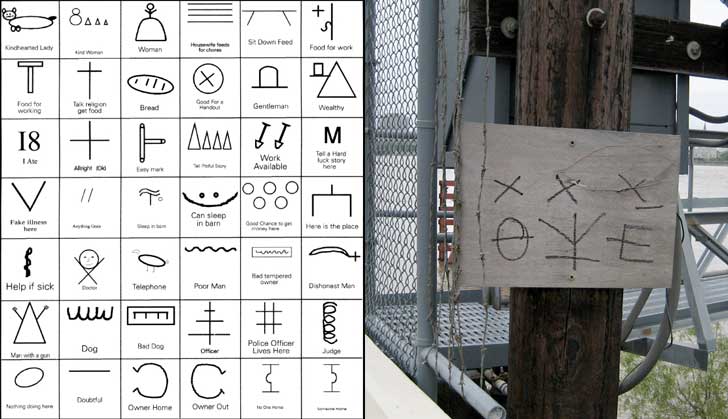

As we previewed in our February 2011 issue, the new Champagne Charlie album is another exercise in plumbing the history of American song, this time to find those tunes written during the heyday of the hobo, in the ‘30s and ‘40s, that most vividly illuminate how these “gentlemen of the road” lived and even policed themselves in their own thriving subculture. Hobo Signs & Railroad Line contains 15 songs from an impressive array of sources--Carson Robinson’s “The Railrood Boomer,” Woody Guthrie’s “I Ain’t Got No Home,” Elizabeth Cotton’s “Freight Train”, J.B. Lenoir’s “Slow Down,” Arthur “Blind” Blake’s “Police Dog Blues,” Big Walter Horton’s “Hobo Blues,” John Prine’s “The Hobo Song,” Harry “Mac” McClintock’s “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” among others. Once again working with the cooperation of The Roosevelt Study Center in Middelburg, The Netherlands (described in the Waitin’ On Roosevelt liner notes as “an academic research institute specialized in modern American history and European-American transatlantic relations”), Champagne Charlie’s Sjef Hermans dug deep into the vaults to study all available information about the hobo’s world--not only songs, but rare books and articles, including some written by hoboes themselves. The result of his research is a liner booklet of impressive sweep. Not only does Hermans offer thorough, succinct background on each song and artist represented on the album, his running text is a compact history lesson in hobo sociology that allows us to hear a familiar song such as “Freight Train” in an entirely different light, and especially the beloved children’s song “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” which turns out to have some serious messages for hoboes hidden in its good-natured, idyllic lyrics. Even the back of the booklet is fascinating--it shows a display of the hieroglyphic-like symbols (real “hobo signs”) hoboes left behind as advisories to those following them, such as a cross (a symbol for “talk religion--get food”), or three blank circles in succession (for “may get money here”) or a rectangular box with a squiggle inside (for “badtempered owner”).

A chart of hobo signs and an actual hobo signWaitin’ on Roosevelt was one of the best album in any genre in 2009; Hobo Signs & Railroad Lines earns that distinction in 2011. As always, Champagne Charlie (Peer Bout, double bass, electric bass; Geert de Heer, mandolin, Andalucia Tiple, banjoline, dobro, lap steel; Peter Lenselink, drums, percussion; Sjef Hermans, lead vocals, acoustic guitar, banjo; Gait Klein Kromholf, harmonica; Theo de Koning, six- and 12-string guitars, banjo) has its infallible internal communication working at its peak on the album’s 15 songs, and as always the band plays not only with great spirit but with great respect for the text of its songs. Elizabeth Cotton’s timeless “Freight Train” even sounds fresh, thanks to the stripped-down banjo-and-vocal rendition by Theo do Koning; and the oft-recorded “Freight Train Blues” contains the whimsical touch of the familiar Johnny Cash “lick.” Everything about Hobo Signs & Railroad Lines smacks of an honest effort flawlessly executed from original conception to final recording and packaging. Makes you glad to be alive, in fact.

The music and the stories behind the songs being so fascinating, we were compelled to check in with Sjef Hermans for more background on the songs and the history Hermans uncovered about them and the hobo life in his extensive research as reported in the liner booklet. It’s seems a safe bet that after hearing Hermans’ report on his research, you’ll never regard hoboes in quite the same way again.

***

Champagne Charlie’s Sjef Hermans: ‘Every traveler who arrived at a hobo jungle was welcome, no matter what race or nationality. The jungle was a social institution with its own rules, regulations, mores and division of labor.’ (photo: Hans de Graaf)The Roosevelt Study Center, which you worked with on the Waitin' On Roosevelt project, is celebrating its 25th anniversary this month and this new CD of yours is part of that celebration. What is the connection between the Study Center and Champagne Charlie as it relates to this album?

The Roosevelt Study Center (RSC) in Middelburg, my hometown, has as its core business the study of U.S. history and culture. This common interest in U.S. history and culture has led Champagne Charlie and the RSC to cooperate over the last few years. The first product of our cooperation was the much acclaimed CD Waitin' On Roosevelt, which was released in 2008 and presented at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Awards ceremony in May of that year. Since then they asked us to participate musically in some of the many international conferences they organized on aspects of U.S. history and culture and U.S.-European relations. It was only natural to continue our cooperation. When RSC director Kees van Minnen heard that we had plans to record a CD with hobo songs, he offered us the chance to produce the album on occasion of the Roosevelt Study Center's twenty-fifth anniversary to be celebrated on September 19, 2011. For my research they gave me all the help they could provide.

I believe all 15 songs on the CD are from 20th Century sources, which of course was the century when railroading transformed America, even though the railroad had been around in some form since the 1820s. What was the earliest reference you found to hoboes riding the rails and where did you find it? How about the earliest railroad and/or hobo song?

Norm Cohen's interesting book Long Steel Rail--The Railroad in American Folksong is the best source for this kind of information. According to his voluminous study the earliest use of the word hobo in print dates from 1891. Cohen presents poems and songs written in the 1870s about tramps wandering around looking for work. The titles of the first songs about this subject are "Because He Was Only A Tramp,” "The Poor Tramp Has to Live" and "Waiting for a Train/Wild and Reckless Hobo.” "Waiting" was one of Jimmie Rodgers biggest hits. It does not mention the term hobo but it describes the way a hobo tries to get a free ride and is thrown off a train while the brakeman calls him "railroad bum," which really was an insult for a real "gentleman of the road."

Champagne Charlie performs ‘Down Town Stomp,’ a song dating to 1927. This is not part of Hobo Signs & Railroad Lines.You etymological investigation into the origins of the word "hobo" is fascinating. Knowing its original meaning, or from whence it was derived, ought to change many perceptions about the hobo right off the bat. What did you learn about the roots of the word?

The origin of the term hobo is uncertain. Through the years, many suggestions have been made. In the introduction of his book Indispensable Outcasts, Hobo Workers and Community in the American Midwest Frank Tobias Thomas Higbie gave a good summary: "The term hobo suggests further complications. Its origin is obscure. Some suggest that it derives from hoe boy, or agricultural labourer, others that it is a shortening of homeward bounders, referring to Civil War veterans, many of whom became seasonal workers in the West. One itinerant worker claimed the term originated from the French haute beau, or ‘high beauty,’ and another from the Latin phrase homo bonus, or ‘good person.’ Still others believed it was simply a crippled version of the railroad workers' greeting ‘Hello Boy.’ Even when people agreed that the hobo was a transient worker, they disagreed on the significance of his transience and his strength of his commitment to work." Men that had been hoboes disassociated from tramps and bums.

A hobo who left an in-depth chronicle of his journeys turns out to be one of your fellow Dutch countrymen. Did you know about Gerard Leeflang before you started this project? Tell me about his hobo experiences in America and what happened to put an end to them.

I had never heard about Leeflang before. I found the title of his book and his name on the Internet. Of course this aroused my interest. I searched book websites from all over the world but I could not find a copy that was available. Much to my surprise I finally found out they had the book in the library of the Roosevelt Study Center, which is just around the corner. For me this is further proof that this institute is an invaluable source of information. In 1923, this young Dutch seaman Gerard Leeflang arrived in New York City. He worked on board several ships as a wireless operator since 1919. During his first visit to the U.S. he was so deeply impressed by the American way of life that he decided to jump ship and stay. This was the start of a three-year odyssey through the U.S. During his travels he worked wherever he could but never stayed long in one place. He plowed, planted and picked corn, but after three years he decided that farming was not his future and went to Chicago. There he finally got arrested as an illegal alien. He had to report to Ellis Island for deportation to his native Netherlands. In 1984, after more than half a century, he wrote a book about his experiences on the road: American Travels of a Dutch Hobo 1923-1926.

Hank Williams, ‘Ramblin’ Man’ (1951) is covered by Champagne Charlie on Hobo Signs & Railroad LinesWithout doing any research to confirm this, I'm willing to bet that most people equate hoboes with bums--you even point out that John Prine, in his wonderful "Hobo Song," which you recorded for this project, refers to hoboes "aimlessly wandering." But the reality was much different--for one, as your notes point out, Jeff Davis, King of the Hoboes, wrote a Hobo Yearbook and Reference Manual for the Hoboes of America in 1938 in which he described his breed as "a gentleman of the road." In researching multiple sources, you found that the common perception of the hobo could hardly be more inaccurate. What did you learn about these people riding the rails all over the country?

In his book Davis gave his opinion on what a hobo was: neither a tramp nor a bum. He certainly called a hobo "a gentleman of the road.” According to him the hobo was the highest in class. A hobo was a migratory worker who was always willing to work to make his way. He could have a special skill or trade, but he could also be ready to work at any task. Tramps travelled too, but they never worked as long as they could make a living out of begging. Bums were the lowest class; they were too lazy to roam around and they never worked. In his great book Hoboes, Bindlestiffs, Fruit Tramps and the Harvesting of the West, Mark Wyman pointed out that the seasonal workers were not only described as hoboes: most harvesters were men, and they became closely identified with the western scene, hopping off freights, traipsing along roadways searching for work, ganging up around employment agencies. Later scholars would define them as "agricultural nomads" or "indispensable outcasts.” They often carried a rolled-up blanket known variously as a bundle or "bindle"--hence their nickname "bindlestiffs." And they were called "hoboes,” "fruit tramps,” "harvest gypsies,” "floaters,” "transients,” "drift-ins,” "apple glimmers,” "almond knockers" and "sugar tramps.”

Apart from Jeff Davis, did the old-time hoboes leave behind much of a printed record of their existence? Did you uncover any obscure gems of prose or poetry that gave you valuable insight into this subculture?

Mark Wyman provided some really interesting books about this subject. He sent me Rebel Voices: An I.W.W. Anthology and a facsimile reprint of the 1923 Little Red Song Book (I.W.W. Songs--To Fan the Flames of Discontent). In 1905 a group of American leading radicals had a meeting in Chicago. They wanted to create a new labor movement. William D. “Big Bill” Haywood, one of the pillars of the Western Federation of Miners, was one of the originators. This convention gave birth to the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), whose members were soon nicknamed the “Wobblies.” The IWW's attack on employers especially appealed to western migratory workers, who were ignored by the American Federation of Labor trade unions. Hoboes and other seasonal workers received little support from anyone--not from employers who wanted them to move on when a job was finished; not from communities little interested in them except at harvest time; and certainly not from most city, state, and federal governmental units. Since migratory workers almost by definition could not vote, they were unable to bring pressures for governmental protection at any level. Their only “safety net” consisted of charities that sometimes provided a meal along with prayers, or kindly jail keepers who would let a hobo sleep in jail on a cold night. Carleton Parker, a California professor investigating labor conditions, said the IWW was recruiting “from the most degraded and unnaturally living of America's labor groups,” itinerants who were “hunted and scorned by society.” Singing was an important outing for the Wobblies. Their song writing became common because they articulated the frustrations, hostilities, and the humor of the homeless and the dispossessed. The official songs were collected in The Little Red Songbook and the IWW continues to update this book to the present time. IWW literature offered an important interpretive venue for the laborers' life experiences, and few items achieved greater popularity. Former hobo Nels Anderson recalled it as “a song-promoting movement” and saw the hoboes' ballads and protest songs bringing “a unanimity of sentiment and attitudes, the strongest form of group solidarity in the hobo's world.” Carleton Parker noted the importance of singing in his report on the 1913 Wheatland riot, observing that even lacking a tightly bound membership, "where a group of hoboes sit around a fire under a railroad bridge, many of the group can sing I.W.W. songs without the book." Joe Hill, the early Wobbly songwriter, who Joan Baez sang about at the Woodstock Festival, wrote IWW lyrics to Christian hymns so the union members could compete with the Salvation Army band that was often determined to drown out Wobbly speakers. He also wrote the IWW signature song for which he used the melody of "Sweet Bye and Bye.” The song was originally named "The Preacher and the Slave" but became famous as "Pie in the Sky" after Carl Sandburg included it in his song collection "The American Songbag" in 1927:

Long-haired preachers come out every night

Try to tell you what's wrong and right

But when asked how 'bout something to eat

They will answer with voices sweet:

You will eat, by and by

In that glorious land up in the sky

Work and pray, live on hay

You'll get pie in the sky when you dieThe limitations of a CD booklet forced me to leave out important parts of my hobo research. We decided to make the complete story available on our website, www.champagnecharlie.nl.

Was the hobo lifestyle an every-man-for-himself proposition or did you find hoboes providing a supportive network for each other as they moved around from city to city, state to state?

Hoboes had their "hobo jungles,” temporary or semi-permanent locations near the tracks, and usually by a water tank, where hoboes would gather in the evening for company and an overnight stay. Every traveler who arrived at a hobo jungle was welcome, no matter what race or nationality. The jungle was a social institution with its own rules, regulations, mores and division of labor. Besides the hobo jungles, larger rail centers also had distinct neighborhoods catering to the needs of travelling laborers. The main street of that area was known by hoboes as the main stem.

Hoboes communicated in their own "lingo,” which contained expressions as diverse as "Hoover or Californian blanket" (a newspaper used to sleep under) and "eat snowballs" (to stay north on the road in the winter). The word-of-mouth information passed on from one hobo to another was nicknamed the “Hobo Gazette.” It was a favored method of finding work in the wheat belt in the mid-1920s. To warn each other the hoboes used so-called "hobo signs,” mostly simple line drawings created from chalk or charcoal. There were regional variations on many of the most common hobo signs, but a dyed-in-the-wool traveler was able to recognize their basic meaning. Roughly from the 1880s until the 1940s, hoboes would leave symbols on fences, sidewalks, street signs and railway stops for fellow hoboes to discover.

J.B. Lenoir performs his ‘Slow Down,’ a tune covered by Champagne Charlie on Hobo Signs & Railroad LinesBluesmen Blind Blake, Blind Willie McTell, J.B. Lenoir and Big Walter Horton are represented with songs on your album, but as your research notes, the majority of hoboes were white males of various ethnicities--a real melting pot kind of community. Were there more blacks riding the rails than were documented, or were the times such that it was simply too dangerous for them to follow white men into that world? Also, weren't the penalties for getting caught jumping a train far more severe for blacks than for whites, as they were in most other legal matters in those days?

In his study Hoboes, Bindlestiffs, Fruit Tramps, and the Harvesting of the West, Mark Wyman confirmed that most hoboes were Americans, white native-born, or were Irish, Scandinavian, German or other immigrants from Northern Europe. Of course there were African-American hoboes, but they were outnumbered by the group mentioned before. Paul Garon and Gene Tomko made a study of "Black Hoboes & Their Songs” and concluded that fitting these African-American travelers into any kind of schematic is a difficult task, not because there were so few of them--although in a relative sense, compared to whites, there were only a few--but because the printed records they left are so sparse.

Treatment by the railroad police, as well as by conductors and brakemen, was variable. At their worst, some "railroad bulls" were ready to shoot hoboes on sight, or at least beat them to the ground and send them to jail. Some dicks got 50¢ a head for any hobo captured, and this bounty was a great incentive. Blacks were treated worse than whites, and often bulls would board a freight and throw off only blacks. In the southwest, whites and blacks were occasionally both spared while the more reviled Mexicans were thrown off unceremoniously. Blues singing hoboes documented their railroad experiences in song. Their efforts to dodge the law frequently failed and the penalty for hoboing in the South was considerably more malevolent than in the North. Men would be sentenced to the chain gang in North Carolina just for hoboing. Blacks were often sentenced to longer terms than whites who had committed the same offense; too, whites would be sent to the state prison, blacks to the chain gang, the former sentence said to be less humiliating and no doubt easier to serve. These experiences became the basis for many a blues.

Elizabeth Cotton performs her ‘Freight Train’ on Pete Seeger’s Rainbow Quest TV show. On Hobo Signs & Railroad Lines, Champagne Charlie’s Thomas de Koning brings it to life in a banjo-and-vocal rendition.Elizabeth Cotton's classic "Freight Train" is on the CD in a wonderful, pared-down version featuring only banjo and vocal. I assume that's Theo de Koning, who deserves a big thumbs-up for both the evocative banjo work--sometimes less is more--and a warm, affecting vocal. Hoboes have invariably been depicted in our culture as being male. You do note the presence of women on the rails in your notes, but how prevalent were they in the hobo world? It stands to reason that it would be a forbidding proposition for a woman alone to join ranks with those men.

Not all the hoboes were men. Among the generally male hoboes traveled a small number of women who sought employment, adventure, and escape from stifling social expectations. Unlike men whose jobs were in the rural hinterland, transient working women moved from town to town seeking urban employment as clerical workers, domestics or entertainers. Often dressed in men's clothing, sometimes with short hair, these "sisters of the road" were less noticed than their male counterparts.

In their book Woman With Guitar, a biography of Memphis blues woman Memphis Minnie, Paul and Beth Garon concluded that in spite of the many references in the blues to hoboing, few are made by or about women. Indeed, female hoboes and wanderers were uncommon during the earlier years that Minnie made her own way from town to town. By the time she gave up this mode of travel, female hoboes were becoming much more common and the Depression was deepening. The Depression put many women on the road, just as it multiplied the number of men already wandering, but women never accounted for more than a tiny percent of the hoboing population. Minnie, about whom Big Bill Broonzy said, "Memphis Minnie can pick a guitar and sing as good as any man,” sang in several songs about her experiences as a young female hobo.

Woody Guthrie, ‘Ramblin’ Round.’ On Hobo Signs & Railroad Lines Champagne Charlie gives Woody’s song a Mexican treatment.As per your version of "Freight Train," I like that Champagne Charlie doesn't take pains to recreate the original recordings of these songs, in keeping with the template you established on your terrific Waitin' On Roosevelt album. Pick out a couple of songs and explain what you did to capture their essence in a different approach that still honors the original sources.

Alright, here they come: “Ramblin' 'Round Your City”: In his book, Mark Wyman wrote about "fruit tramps" from Mexico who were treated even worse than Afro-Americans. In the 1920s Mexican families in Texas” were travelling aimlessly through the country, living in tents and picking up whatever work they could find. Like the African-Americans the Mexicans sang to lighten the hard labor they had do. These Mexicans frequently described their hard life in corridos--(narrative) songs they created and sang at their gatherings. Some were composed while they worked in the fields, their cotton bags dragged behind, the sun beating down. Wyman inspired us to give Woody Guthrie's song a Mexican treatment. Our "string marvel" Geert de Heer even borrowed a tiple (a Mexican small 12-string guitar) to create the sound we needed.

“Hobo Blues”: Gait Klein Kromhof, our harp player who was honored earlier this year with the Blues Award for Best Dutch Harmonica Player, wanted to record a short instrumental. He chose a tune that was recorded by his model "Big" Walter Horton and subsequently played it his own way. He does not copy, he makes his own interpretation. You have to dig up the deep roots and make mileage before you can say that you have your own style.

“The Hobo Song”: In his original version John Prine included a spoken part. That inspired me to tell the whole story instead of singing it. It is like a hobo who is telling a story to his comrades in the hobo jungle and then they all join in during the chorus.

Goebel Reeves, if he's known at all outside folk circles, is known for writing "Hobo's Lullaby," a song recorded by Woody and Arlo Guthrie both, and probably widely considered a Woody song. Reeves, though, was a fascinating character who wrote and recorded a lot of hobo songs--30, you say in your notes--but took it a step further and actually became a hobo. Clue our readers in on his incredible story.

Goebel Leon Reeves, who called himself "The Texas Drifter,” was one of the many singers who kept the hoboes alive in their songs. Between 1929 and 1935 Reeves recorded more than 30 songs about hobo life. He decided to become a hobo himself after he met one when he was still a kid. He served in the American Army during World War I and the trip to Europe made him eager to see more of the world. Upon his return from the war Goebel Reeves commenced the life of an itinerant. His family did not like that at all, and hoped that it was a phase he would outgrow. He never did. In his songs he used all three terms, hobo, tramp and bum; they had titles such as "At The End Of The Hobo Trail,” "The Tramp's Mother" and "The Railroad Bum.” Indeed, both Guthries recorded "Hobo's Lullaby," but the version recorded by Emmylou Harris for the Lead Belly/Guthrie tribute A Vision Shared really puts a man to sleep.

Blind Blake’s ‘Police Dog Blues’ is covered by Champagne Charlie on Hobo Signs & Railroad LinesA lot of great artists in blues, folk and country have recorded "Freight Train Blues," but CC specifically references Johnny Cash by using his familiar lick at the beginning and end of your version. Do you have special affection for Cash or for Cash's version of the song that you wanted to acknowledge with this identifiable Cash "quote"?

Cash has always been a big influence to us. He recorded many train songs and sometimes sang about hoboes. The using of this universally known lick is a tribute to the man's great music. Another model is Jimmie Rodgers. We did not select one of his songs because his repertoire has been covered so many times by so many artists. The proof for this is Barry Mazor's excellent book Meeting Jimmie Rodgers--How America's Roots Music Hero Changed the Pop Sounds of a Century. And of course there is another reason: I cannot yodel.

Harry ‘Mac’ McClintock’s original version of his ‘Big Rock Candy Mountain,’ with actual, unsynched footage of McClintock performing. Champagne Charlie covers McClintock’s classic on Hobo Signs & Railroad Lines.One of the big surprises this album held for me was learning from your research that Harry "Mac" McClintock's "Big Rock Candy Mountain" was to the hoboes much more than the folk or western or children's song that I grew up with. It has a deep meaning for hoboes. Why was it a special song for them?

"The Big Rock Candy Mountain" is the ultimate hobo's dream. Whenever hoboes gathered each had a story to tell about food. It began with a brief and sketchy description of the circumstances under which the meal was obtained, then a long, complete, detailed and drooling description of each item of the food followed. And these stories always ended with: "and three cups of coffee..." The afterlife offered in the song '"The Big Rock Candy Mountain": no police, dogs with rubber teeth, always good weather, no need to change your socks, and a land overflowing with food, liquor and cigarettes was not abstract for hoboes. It was the "Hobo's Dream.”

Finally, the question I have to ask each time we correspond: When are we going to get to hear Champagne Charlie playing live in the U.S.?

That is a good question. For us that would be really something, like climbing "The Big Rock Candy Mountain.” The absolute top would be playing in front of Little White House in Warm Springs, Georgia. Just like Bun Wright's Fiddle band did for FDR in the early thirties. That's our own little "Hobo's Dream.”

TheBluegrassSpecial.com’s exclusive feature on the making of Champagne Charlie’s Waitin’ On Roosevelt album is in our May 2009 issue.

A preview of Hobo Signs & Railroad Lines as an album-in-progress appeared in our February 2011 issue.

Champagne Charlie's Hobo Signs & Railroad Lines is available at www.champagnecharlie.nl

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024