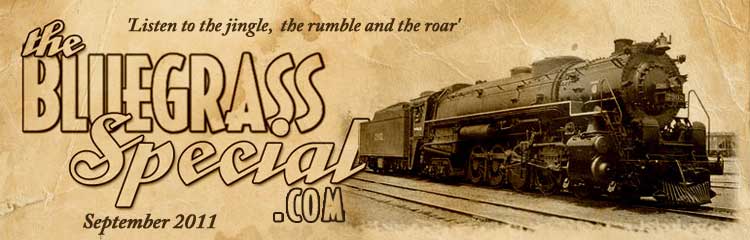

(left) Elvis duirng his final apperance on the Louisian Hayride, December 15, 1956; (right) in front of the New Frontier Hotel, Las Vegas, April 1956‘What Is Going On?’

In 1956 Elvis’s guitarist, Scotty Moore, asked the question. Elvis supplied the resounding answer. A new box set chronicles a momentous year for the man who would be King.

By David McGee

YOUNG MAN WITH THE BIG BEAT

Elvis Presley

RCA/LegacyOn November 28, 1955, a week after RCA Victor had bought Elvis Presley’s contract from Sun Records for $35,000, the campaign to promote the artist’s first single began. To introduce Presley as an RCA artist the label was re-pressing and reissuing his final Sun single, “I Forgot To Remember To Forget”/”Mystery Train,” after it was petering out on the national country charts. The promotional campaign for the single included a note to retailers and distributors from John Burgess, Jr., RCA’s manager of sales and promotions in the Single Record Department. Burgess wrote emphatically: “The NAME: Elvis Presley, one that will be your guarantee of sensational plus sales in the months to come!” Given what happened in 1956 and thereafter, Burgess’s restraint is admirable.

Elvis and his band--guitarist Scotty Moore, bassist Bill Black and new member D.J. Fontana, the former Louisiana Hayride house drummer who had joined the group in August--supplemented in the studio by Floyd Cramer and Shorty Long on piano, the Jordanaires and gospel stalwarts Ben and Brock Speer, under the guidance of Chet Atkins, had cut their first RCA sessions in January and February 1956 with an eye towards releasing a long playing album along with some new singles. Like their Sun labelmate Carl Perkins, Elvis, Scotty and Bill had become used to seeing not merely young people at their shows, but frantic young people, teenagers largely, whose reaction to their fresh, rhythmically charged music was both electrified and, for the musicians, electrifying.

In late February ’56, playing the Hayride, one of the first places to welcome the young Hillbilly Cat at the beginning of his professional career in 1954, Elvis rolled out one of songs he’d cut at his first RCA session on January 10. “Heartbreak Hotel,” written by Tommy Durden and Mae Boren Axton, had been released as a single on January 27 and was well on its way to making John Burgess, Jr.’s prediction of “sensational plus sales” seem like a gross understatement.

As Peter Guralnick recreated the moment in the first volume of his definitive Presley biography, Last Train To Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley (Little, Brown and Company, New York 1994): “They were back on the Hayride the following week for the first time in a month. A lot had happened in that month, but for Elvis and Scotty and Bill there had been no time to gauge it, and it didn’t appear all that different from everything else that had been building and going on for the last year. They did ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ for the first time, said Scotty, ‘and that damn auditorium down there almost exploded. I mean, it had been wild before that, but it was more like playing down at your local camp, a home folks-type situation. But now they turned into--it was different faces, just a whole other… That’s the earliest I can remember saying, What is going on?’”

Elvis performs ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ on The Dorsey Brothers Stage Show, February 11, 1956What was going on was nothing less than a complete, across the board revolution in show business as a whole, in music specifically, in popular culture, in the business of marketing and promoting to a new and burgeoning teen demographic, in fashion, in mores and values--a movement with political and social ramifications yet to be stilled and felt the world over (your faithful friend and narrator recalls the late, great Jerry Leiber telling of an explorer friend who returned from a safari to darkest Africa circa 1957 with news of Elvis Presley being only thing American familiar to the uncivilized tribes he had encountered).

It started with the music--with Elvis’s remarkable feel for blues, gospel, rhythm and blues, pop and country and the wild, unbridled energy of the singing and playing--and exploded, when the music moved through his body onstage, with a fury well suited to the Atomic Age. There’s a reason Guralnick needed two long volumes in order to grasp the phenomenon of Elvis Presley in all its complexity; there’s a reason Elvis books are a cottage industry; there’s a reason his Graceland home keeps drawing visitors, with a high percentage of those likely having no memory of Elvis as a live human being. With its smart reissue campaign of Elvis recordings, most especially those comprising last year’s 75th birthday celebration (culminating in the magnificent 27-CD set, The Complete Elvis Presley Masters, containing all 711 of the King’s master recordings released during his lifetime), RCA/Legacy could hardly do more to remind anyone who’s paying attention of how, indeed, it all started with the music. The label has done still more, by way of Young Man With the Big Beat, a new five-CD box set chronicling the moment of greatest change in American music--the release of the first two Elvis Presley RCA albums in 1956, along with the single sides responsible for his domination of the charts and public discourse in his first year as a major label artist. At the same time, these albums, Elvis Presley and Elvis, serve as both a template for Elvis’s music in the years to come and the legitimizing of the album as a credible medium of communication for rock ‘n’ roll artists in an era when the single ruled. Among his contemporary rock ‘n’ roll pioneers, Elvis the album artist was challenged on that front only by Chuck Berry, whose Chess LPs would pivot from his great rock ‘n’ roll hits into scintillating blues and R&B (even a taste of country) excursions. (A case could also be made for Little Richard in this regard, but his Specialty albums, however potent, were less stylistically diverse than those Presley and Berry offered.)

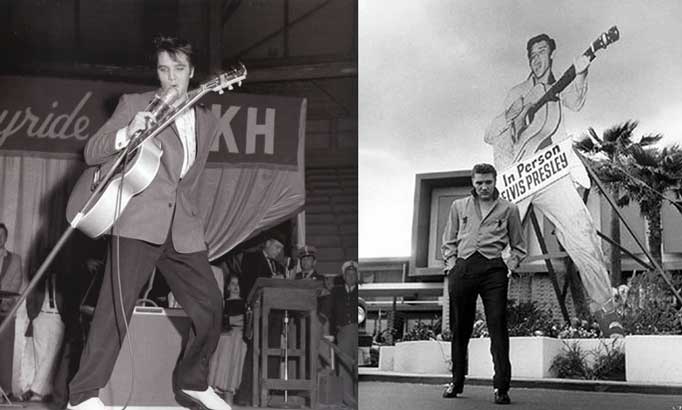

On November 1, 1956, Elvis bought a new Harley. Late that day Natalie Wood, clad in jeans, climbed up on the seat behind Elvis and they gunned out from the driveway of the Presleys’ Audubon Drive home and roared around the Memphis streets for three hours accompanied by a motorcycle policeman and actor Nick Adams, who was riding Elvis' old Harley Davidson.The heart of the five CD set is the two discs of Original Masters (the first two albums plus the non-album singles). Three other CDs flesh out the story of a landmark year in American music. A disc of outtakes (some previously released, some seeing the light of day for the first time) is pretty well narrowcast for Elvis die-hards who have a vested interest in hearing, say, 11 of the 12 takes of “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” or the same number of runs at “Shake, Rattle and Roll.” The real attraction of the Outtakes disc is the inclusion at the end of a 30-minute interview with Elvis conducted by trade journalist Robert Brown at New York’s Warwick Hotel on March 24, 1956. With little biographical detail then available about Elvis, Brown begins the questioning with Elvis’s self-recording at Sun and his job as a Crown Electric truck driver. Given how few interviews with Elvis exist, it’s still fascinating to hear him talk about how determined he was to make something of himself at Crown Electric, telling Brown that “during the time I was working for the electric company I was in doubt as to whether I would ever make it or not, because you have to keep your mind right on what you’re doing; you can’t be in the least bit absent-minded or you’ll blow somebody’s house up. I didn’t think I was the type, but I was going to give it a try; I was going to devote all the time I could to learning it.” His own words betray the discipline and drive both Johnny Cash and Carl Perkins saw in Elvis that not only inspired them but also left no doubt in their minds as to his eventual success as an entertainer. Brown questions Elvis about minutiae such as what he wears when he rides his motorcycle, but he also gets into music, eliciting from Elvis that Sonny James was one of his favorite artists of the moment, although Elvis is quick to add, “I like anybody that’s good, regardless of what kind of singer they are, whether they’re religious, rhythm and blues, hillbilly, or anything else. I mean, if they’re great, I like ‘em, from Roy Acuff on up to Mario Lanza. I just admire them if they’re really great, if they’ve really built a thing for themselves.” The last phrase--"if they've really built a thing for themselves"--constitute the most revealing words Elvis ever spoke about himself in public; even though he was not speaking directly about himself, he was speaking to ambition, to goals, to a vision he made reality. Elvis expresses an interest in recording a gospel album, praises Frank Sinatra and, again, Mario Lanza, appraises his debut album, discusses audience reaction to “fast numbers” as opposed to ballads; of his fans, he says, “I wish there was some way you could go around to each one of them and show them how much you appreciate them.” It’s tempting to keep quoting from the interview, it being the longest available conversation with Elvis and the most revealing, as far as it goes.

Elvis performs Carl Perkins’s ‘Blue Suede Shoes’ on the Milton Berle Show, April 3, 1956, aboard the U.S.S. Hancock. Elvis’s recorded version was featured on his self-titled RCA debut album.Most of the box set’s The Live Performances CD has been previously issued, including the infamous May 1956 show at the New Frontier Hotel in Las Vegas when Elvis’s appearance generated negative press (the muted response from the Vegas audience is a tipoff that things aren’t going so well, and Elvis in turn is straining to be congenial) and left a sour taste in his mouth--he returned to Memphis, walked in on a Carl Perkins session at the Sun Studio and vowed to Carl, his band, Jerry Lee Lewis (who was playing piano on the session), Sam Phillips and Johnny Cash that one day he would return to Vegas and be the highest paid artist in Sin City’s history; less than two weeks after his Vegas debacle Elvis was holding forth at the Robinson Memorial Auditorium in Little Rock, as heard here, and the young folks in attendance--seemingly all girls judging from the screams that drown out all other audience response--are in a frenzy, almost subsuming Elvis’s vocals in adolescent howls at times. The previously unissued performance on this disc is from mid-December 1956, at the Hirsch Youth Center in the Louisiana Fairgrounds complex, where the audience is even more crazed, but Elvis is also more assured. At times he laughs at the response to his work, and particularly enjoys pushing the audience’s hot button during a grinding, extended, near-five-minute version of “Hound Dog.” Those Elvis detractors who have made sport of Elvis’s late-life tendency to mangle the words of his songs, as if that were clear evidence of his decline, might want to dig this disc of 1956 shows: at the New Frontier, he changes “Heartbreak Hotel” to “Heartburn Hotel” near the end of the song; at the Robinson Memorial Auditorium show, an intense, rather amazing version of “Heartbreak Hotel”’s great B side, “I Was the One,” which Elvis cites as his favorite song in the Warwick Hotel interview with Robert Brown, finds him singing, “Who learned a lesson…when she broke my leg...I was the one.” Focus on this, dear readers, on pain of missing the subtleties of the vocal, which employs blues and gospel flourishes to enhance the hurt and the regret fueling the singer’s self-recrimination. Stay tuned after “I Was the One” for a blistering take on Jesse Stone’s Clyde McPhatter-era Drifters hit, “Money Honey,” one of the most incendiary performances on any Elvis live disc, although it pales a bit in comparison to the scorched earth left in the wake of Scotty Moore’s guitar hailstorm, D.J.’s machine-gun drumming and Elvis’s merciless delivery on Ray Charles’s “I Got a Woman.”

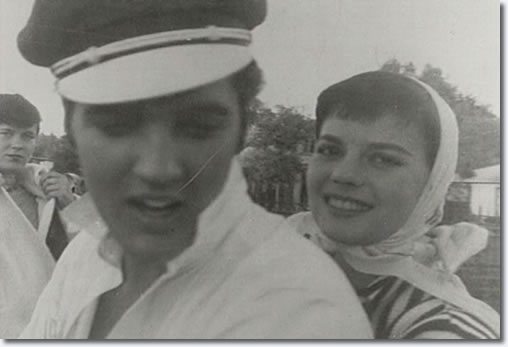

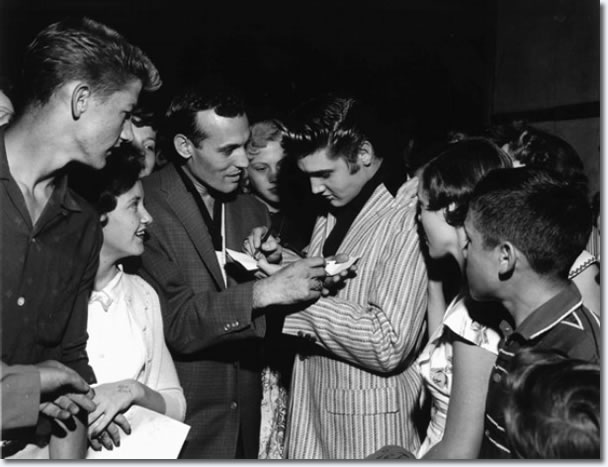

Carl Perkins and Elvis sign autographs at Overton Park Shell in Memphis, June 1, 1956The Elvis of the Warwick Hotel interview is a bit--only a bit--more polished and guarded than the Elvis heard in the 27-minutes-plus TV Guide interview from August 6, 1956 leading off Disc 5, The Interviews. Speaking in a much thicker Southern drawl and seemingly on edge, Elvis gets testy when reporter Paul Wilder quotes from an especially vindictive and gratuitously cruel review of both his artistry and his audience, the latter invective causing Elvis to lash out, objecting to his fans being called “idiots” by remarking that someone who would say such things must be an idiot himself and “should be slapped in the mouth.” To being called “the biggest freak in show business history” and a “no-talent performer” a bruised Elvis replies with a curt, “I don’t even wanna think about it. He hates to admit he’s too old to have any more fun, you know.” To the critic’s denigration of Elvis’s audience as “two thousand screaming idiots” Elvis answers: “Sir, those kids that come here and pay their money to see this show come to have a good time. What’s-his-name here might’ve had a little fun when he was young, but I doubt it. I’m not running him down, but I don’t see that he should call those people idiots, because they’re somebody’s decent kids, probably raised in a decent home. He hasn’t got any right to call those kids idiots. If they want to pay their money and come out and jump around and scream and yell, it’s their business. They’ll grow out of that. But while they’re young let ‘em have their fun; don’t let some old man who’s so old he can’t get around sit around and call ‘em a bunch of idiots. They’re just human beings like he is.” The more reporter Wilder confronts Elvis with the attacks on his music, character and audience, the more articulate and firm Elvis becomes in his and their defense, much as he did in an interview not included on this disc, with a North Carolina radio station, if memory serves, in which he offered a warm tribute to the black artists and black music that had and continued to influence him. Elvis is also heard here on his only spoken word recording, “The Truth About Me,” a two-minute monologue about his music and his life that was issued only as a flexi-disc on the cover of a teen magazine in 1956; a longer version of “The Truth About Me” is a Q&A interview issued as a 45 RPM disc in Teen Parade magazine in which Elvis, on the set of Love Me Tender, coolly answers pre-recorded questions from an unidentified interlocutor.

Elvis on The Ed Sullivan Show, October 28, 1956, performs Leiber-Stoller’s ‘Love Me,’ from his second RCA album, Elvis, included in the Young Man With A Big Beat box setEven more rare than Elvis interviews are interviews with his notorious manager, Col. Tom Parker. One of those, possibly the only one, also conducted by TV Guide’s Paul Wilder, follows Wilder’s Elvis interview. Smooth, reserved, unruffled, the Col. fields a variety of questions about Elvis’s appeal, the frequency of his television appearances (the Col. defends his strategy of limiting Elvis’s TV appearances to avoid overexposure, even though, as Gurlanick detailed, mass exposure via TV was central to the Col.’s marketing plan for his young charge), Elvis vs. Marilyn Monroe as cultural icon (“I haven’t read too many stories about Marilyn Monroe. Maybe she should be on television and she’ll be getting the publicity we’re getting on Elvis Presley,” the Col. boasts), Elvis’s press critics (ever diplomatic, the Col. says “they have a job to do. I believe most of them who write a story on Elvis Presley have never seen him perform.”) and various other issues. Suffice it to say the Col., in his public pronouncements, is firm and businesslike, with answers always at the ready, diplomatic throughout, and speaking in impeccable, unaccented English, not the “Elmer Fudd accent” others have attributed to him. The old carny knew how to charm when the occasion demanded it, a skill he had perfected in his life as illegal immigrant Andreas Cornelis van Kujik from the Netherlands (where it has been reported that he was a suspect in a murder case in his teens), con man, Army deserter and music promoter/manager.

Of course all else pales in comparison to the two discs of Original Masters from the first two album sessions. These alone shame those Elvis mythologists who so fervently wish he had vanished back into the Lauderdale Courts after cutting the first five Sun singles, and inveigh against his signing with RCA as marking the onset of a precipitous decline in his artistry. There is, of course, no evidence to support this position. In fact, the evidence on the first two albums renders such claims laughable, unworthy of serious discussion. The argument that Elvis never sang with a greater sense of freedom than he did on “Mystery Train” is refuted repeatedly by his raucous performances of Brother Ray’s “I Got a Woman” and his first Leiber-Stoller cut, “Hound Dog,” a masterful demonstration of blues belting; by his intensity and sense of drama on “Heartbeak Hotel”; by the sheer abandon of his rhythmic attack on Arthur Crudup’s “My Baby Left Me”; by the eager country bounce and unbridled joy in his interpretation of “When My Blue Moon Turns to Gold Again.” Even in rushing through his versions of “Blue Suede Shoes” and Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” he sounds unrestrained, unfettered, at large, exulting in the moment.

‘First in Line,' from Elvis, the King’s second RCA album: melding the wistful with the metaphysical, singing from so deep inside the song that the song has consumed himWhat was hinted at in his Sun recordings flowers fully in his first RCA sessions and would remain one of his strengths to the end of his life, to wit, his balladry. Two tracks recorded at Sun in 1954 and featured on Elvis Presley--Leon Payne’s “I Love You Because” and Rodgers and Hart’s pop chestnut “Blue Moon”--were a strong demonstrations of his advanced understanding of pop nuance; fragile and aching, the tenderness in his voice is gripping, whereas his probing of the lyrics for deeper shades of meaning produces an emotional engagement quite rare in one so young and inexperienced in the world. From the second album, Elvis, a Leiber-Stoller blues ballad, “Love Me,” was so strong an articulation of yearning with a pronounced undercurrent of outright lust, that it became a beloved Elvis song without ever being a single. In the studio Chet Atkins had constructed his own kind of echo chamber out of admiration for the Sun slapback he admired on Sam Phillips’s records, and it worked to great effect on Elvis. But it was most effectively--most devastatingly, to be accurate--deployed on the Aaron Schroeder-Ben Weisman love song “First In Line,” when Elvis responded to the lyrics’ rapturous litany of a woman’s compelling physical attributes--“eyes like diamonds,” “lips like honey”--and a corresponding plea for connection--“don’t refuse me, say you’ll choose me”--with a vocal abstract in melding the wistful with the metaphysical, delivered from so deep inside the song that the song has consumed him. Yet he’s in control all the way, perfectly composed to imbue the final hopeful couplet--“my darlin’, say I’m your darling/the first and the last in line”--with gentle, humble sincerity. Unusually constructed for a ‘50s love ballad, with a bridge but lacking a chorus, “First In Line” inspired what still stands as one of Elvis’s monumental ballad performances--his first great ballad performance, in fact--a moment when he was working on a lofty plane of instinct, intuition and heart.

Brad McCuen, RCA’s southern regional representative, and Chick Crumpacker, RCA’s head of country and western promotion, are the unsung heroes of Elvis circa 1956. Having heard Elvis’s first Sun single in 1954, and noting the stir it caused, McCuen bought a copy and sent it to Crumpacker in the New York office. A Northwestern School of Music graduate and classical composer who loved American folk music, the erudite Crumpacker responded positively to McCuen’s urgings to catch Elvis onstage when Crumpacker came south on business. After seeing Elvis perform, noting the kids’ “galvanic” reaction to the show and then meeting Elvis over breakfast the next morning with the Colonel, Crumpacker bought all four of Elvis’s Sun singles--two sets in fact--and sent one set to RCA’s country and western head, Steve Sholes, who signed Elvis to RCA before the year was out.

‘How Do You Think I Feel,’ from Elvis, the second RCA albumCrumpacker not only “discovered” Elvis for RCA, he wrote the liner notes for the Elvis album. Unlike the typical ‘50s liner notes for popular music albums--even unlike the liners for Elvis’s eponymous first album, which amounted to a capsule biography with an adulatory signoff describing the artist as “the most original protagonist of popular songs on the scene today”--Crumpacker’s essay made a sober, sensible case for Elvis as a folk singer with roots in R&B, the traditional country of Jimmie Rodgers and southern gospel. Not only was this the beginning of serious Elvis scholarship, the notes mark the origin of serious rock criticism.

Completely avoiding the fluffy, gee-whiz hype of the teen fan mags of the day, Crumpacker added context to Elvis’s accomplishments, examined the deep roots of his music and how those shaped the sensibility of someone who could sing Red Foley’s lachrymose country tearjerker about a boy and his dog, “Old Shep,” as convincingly as he could wail Little Richard’s “Rip It Up” or prance through the Latin-tinged country of “How Do You Think I Feel.” Opening with six paragraphs describing the anticipation for and the resulting furor over the first appearance on national TV “of a country singer unknown to the pop world, a youngster of unusual talents with some uncertainty about displaying them before a national audience,” the writer went on to note how, in the wake of a sensational performance, the critics’ “analytical sour grapes soon turned into useless vinegar, or else were sweetened by the critics’ ‘discovery’ of Presley’s talent in time.” The ensuing exploration of the “Why?” of Elvis’s “wildfire popularity” bears reprinting as the definitive statement on the source of Elvis's appeal, then and now:

Of commercial folk music Presley is perhaps the most original singer since Jimmie Rodgers. His rhythmic style derives from exactly the same source of Deep South blues and jazz as that which inspired the late Blue Yodeler. Nor is it any coincidence that their birthplaces in Mississippi are less than a hundred miles apart.

Some say it is a reaction to present-day confusion that has caused rhythm and blues writers to simplify their songs with repeated tones and a heavy after-beat--in other words, to create rock and roll. If so, Presley was the first to extend it to the Rodgers interpretation, followed with his own. As the album cover dramatically illustrates, however, his folk characterization is still most natural and forthright.

Presley’s belting delivery accounts for a truly sensational reaction among teenagers. Important to this is his enthusiasm for music by the Blackwood Brothers, the Statesmen and other quartets of the South. There has never been a great difference between rhythm and gospel songs except, of course, for the lyrical content: in fact, the latter are far more rhythmic where staging is concerned. It is essentially the fervor, the animation and boundless spirit of gospel singing that Presley admires and which has been absorbed into his own dynamic performances.

We can better understand this if we consider how often “revival” numbers have hit in the popular field. Here, Presley favors beat and ballad singers alike in such different personalities as Billy Daniels and Bill Kenney--which leads to this possible answer for the “Why?” of his unprecedented appeal: Elvis Presley, by combining the four fields (country, gospel, rhythm and pop) into perfect unity, is unique in music annals and experience. At this point we must leave influences behind and discuss Presley in his own right, or, better yet, (since this is the point where publicity begins), leave the subject altogether and listen to the music.

Of special note is the piano accompaniment in Old Shep, the first that Elvis Presley ever recorded himself, also the superb backing of the Jordanaires, who have assisted on several of his important singles. In scope, we feel that this collection is unsurpassed for variety by any artist and will serve to win an even greater Presley following. For, in addition to the chill wind that penetrated Broadway on that memorable January night, there entered a new breath of life into the musical world--one that has just begun to vitalize the imagination of listeners everywhere.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024