Doing It Their Way

Sinatra and Bennett, captured at pivotal moments

By David McGee

RING-A-DING-DING

Frank Sinatra

Concord Records

THE BEST OF THE IMPROV RECORDINGS

Tony Bennett

Concord RecordsFor two masters of the Great American Songbook, the years 1960 and 1975 occupy an important evolution in their influential careers. In 1960 Frank Sinatra, on a professional hot streak as an actor, recording artist and live entertainer, was at the end of his Capitol Records contract. Eager to try his entrepreneurial hand, he decided against re-upping in favor of establishing his own label, Reprise Records. Capitol tried to dissuade him, failed, and then refused to allow the Chairman of the Board’s favorite arrangers, Nelson Riddle and Billy May, to produce Sinatra on a freelance basis. Undeterred, Sinatra moved on. By contrast, in the early ‘70s Tony Bennett was feeling, with justification, unappreciated and misused by Columbia Records, where he had started his career in 1950. When his contract came up for renewal in 1973, he signed instead with MGM. Two years later he followed his buddy Sinatra’s example and with a business partner launched his Improv label. Neither Reprise under Sinatra nor Bennett’s Improv had a long life--Sinatra cashed out for $3 million in 1963; Bennett, who had struck a distribution deal for Improv with Columbia, folded the venture after 1977 and returned to the Columbia fold, where remains to this day (he celebrated his 85th birthday last month and later this month will release Duets II, a sequel to his 2006 multi-platinum Duets).

In their own way--because both of these towering artists must always be considered “in their own way”--Sinatra’s Ring-A-Ding-Ding Reprise debut and the Bennett single-disc anthology The Best of the Improv Recordings reflect a certain sense of both artists feeling unshackled, free, fully the artists they wanted to be. Sinatra would go on to add to his daunting catalogue, but the ensuing two decades-plus of recordings had spotty moments, mostly centering on his attempts to record less sophisticated contemporary material (he no doubt would wish “Moody River” banished from his history) than his customary high-minded fare from the great pop songwriting masters he had always championed; still, his final studio album, 1981’s Don Costa-produced She Shot Me Down (incredibly, now out of print in the U.S.), was a masterpiece of desolation, loneliness and remorseful reflection on a par with monuments from the Capitol years such as Sings For Only the Lonely and In The Wee Small Hours. Bennett would take his Improv template--subdued, reflective sessions with an orchestra, a jazz quartet and, most notably, with only himself and jazz piano titan Bill Evans--and run with it right up to the present day. This has led him into fertile territory and since the ‘90s has resulted in a greater appreciation for his artistry than he has ever experienced--albums such as The Playground (a 1998 collection of classic pop songs expressly aimed at children) and warm, lovingly rendered tributes to Fred Astaire (1993’s Steppin’ Out), to Sinatra (1992’s Perfectly Frank), to the great female vocalists of his time (1995’s Here’s To The Ladies), and to Billie Holiday (1997’s Tony Bennett On Holiday) are remarkable statements from an artist bringing the full weight of his life’s experiences to bear on songs pondering the greater import of people who need people--songs about love, about friendship, about the complexities of relationships romantic or platonic.

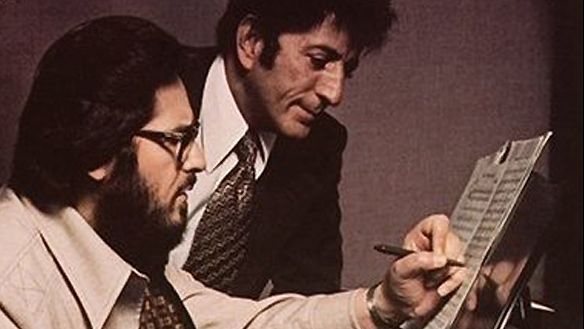

Tony Bennett and Bill EvansThe 16 selections culled from the Improv years for The Best of the Improv Recordings begin the journey Bennett continues today in his 85th year. The earliest cuts are from 1973, pre-Improv sessions financed and produced by Bennett himself in New York with the Ruby Braff/George Barnes Quartet, which consists of Braff on cornet, Barnes and Wayne Wright on guitars and John Guiffrida on bass. Rodgers and Hart’s “This Can’t Be Love” rolls out in a relaxed swing arrangement, with Bennett almost whispering the lyrics at times, his voice full of wonder and a shade of disbelief at his good fortune, in a tight, propulsive but low-key arrangement sprinkled throughout with Braff’s roller-coaster cornet lines and the electric guitar’s steady, full-toned strum. This interior approach--warm, probing, affectionate, with understated effervescence--is one Bennett embraced thereafter; in fact, on, say, Tony Bennett on Holiday, his Billie Holiday tribute, all the arrangements are informed by the various configurations he works in on the Improv selections here. Seven cuts with Braff/Barnes are uniformly heightened demonstrations of the power of restraint to generate a special heat of its own--witness “Blue Moon” in a moody, ruminative version beginning with the seldom-sung opening verse, then enlarged by bluesy support from Braff’s muted, weepy cornet, and “Isn’t It Romantic,” dreamy and seductive, with a lovestruck Bennett imbuing the lyric “isn’t it romantic, on a moonlight night she’ll cook me onion soup” with an expectation of greater rewards beyond that moment, if you get his drift.

Tony Bennett, ‘As Time Goes By’ with the Ralph Sharon Trio. For his Improv label Bennett recorded the tune with a trio and orchestra led by Torrie Zito.Needless to say, Bennett was no stranger to the orchestral approach, and at Improv he worked in that style with Torrie Zito, then his regular musical director. Still, he kept the flame on medium in the arrangements, while deploying his voice in all its colors and muscle to maximize the narratives’ emotional resonance. The masterful take on Mercer Ellington’s “Reflections”--another song celebrating the onset of new love--finds Bennett both belting (his triumphant “at laaassst!” at the end of a song is an especially riveting coda) and quietly searching in imparting something holy about a moment long-awaited but unexpected, in a performance bolstered subtly by Zito’s lovely, ascending string arrangement that takes care to shadow but not overshadow the singer’s sublime exultation. The fun he has with “As Time Goes By” (again singing a seldom-heard verse), in which he takes a near-conversational tone in describing the wisdom of how “the fundamental things apply,” with a nice kick from the horn section as the strings hum soothingly in the background, is a refreshing, upbeat take on the time-honored rendering of this classic, and in even in making it brassier than usual Bennett still honors the song’s inherent romantic disposition.

Tony Bennett and Bill Evans, Comden-Green-Styne’s ‘Make Someone Happy,’ from the Tony Bennett-Bill Evans duet album, Together Again, released on Bennett’s Improv label in 1977, included on The Best of the Improv RecordingsIn Bennett’s entire catalogue few of his recordings are more highly regarded than his two duet albums with the brilliant but troubled jazz piano giant Bill Evans. Four of those cuts are included here, and feature passion uncommon even to the other outstanding selections comprising this disc. Bennett’s singing is at its jazziest but also at its most controlled, leaving plenty of room for Evans to work scintillating theme-and-variation passages when he steps out--the way he takes off skittering across the keys on the break on “Make Someone Happy” and then gently sets up Bennett’s final vocal volley is nothing less than breathtaking; it’s as if he was out there in the ether, heading for a destination known only to him, in an anxious, breathless sprint on a circuitous route, a winding road, that brings him back for a gentle landing at his departure gate, in just enough time for the singer to bring it all back home. Conversely, on “You Don’t Know What Love Is,” the only despairing song on the album, Bennett seethes at low flame in addressing one who simply doesn’t get it when it comes to heartache, all the while with Evans shadowing him sensitively, hewing to the melody, every plaintive note reflecting the ache Bennett pours into a lyric such as “you don’t know how hearts burn for love that cannot live yet never dies/until you’ve faced each dawn with sleepless eyes…”--Evans’s wistful soloing recalls the beautiful sorrow of his “Remembering the Rain,” from his 1978 New Conversations album. The Bennett-Evans tracks--all produced, by the way, by Evans’s trusted studio cohort Helen Keane in her usual clean, uncluttered style--retain all their luster, as do the other Improv recordings, none of which had the commercial success of his Columbia sides, all of which are essential to understanding Tony Bennett.

Whereas Bennett exudes the freedom of an artist in the process of redefinition, Sinatra advances a different kind of freedom on Ring-A-Ding-Ding: not that of an artist needing a reboot, so to speak, but that of an artist, secure and in charge of his identity, sensing a potentially seismic shift--cultural, political, scientific, what have you--looming in the land. Remember his buddy (at least then) John F. Kennedy was in the White House and in his inaugural address had announced the passing of the torch to a new generation. In making his debut on and at once introducing Reprise, he seized the energy of the moment; it’s all over the album, suffusing Johnny Mandel’s animated orchestral arrangements and animating the Chairman’s insouciant delivery. In contrast to his concept albums, Ring-A-Ding-Ding lacks a storyline, character development and narrative arc. What you’ve read about the album in this paragraph is all the subtext there is, save for Capitol’s refusal to let Nelson Riddle and Billy May work with Sinatra. (Another Sinatra favorite, Gordon Jenkins, was ruled out owing to his bold, classical style of arranging and composing, which would have been a bad fit for a project Sinatra always intended to be a swing album.)

For the critical job of guiding the studio sessions and fashioning fresh arrangements of songs from the portfolios of the great writers he had always favored, Sinatra selected the then-relatively obscure Johnny Mandel, a bit of a recluse known primarily for his highly regarded score for Robert Wise’s taut 1958 drama I Want to Live!, a Susan Hayward vehicle about a woman double crossed and sentenced to death for a murder she didn’t commit. Mandel, whose film score was performed by a band featuring Art Farmer, Gerry Mulligan, Bud Shank, Red Mitchell, Pete Jolly, Frank Rosolino and Shelly Manne, was fast gaining a reputation as an inventive jazz writer, and Sinatra liked what he had heard. Mandel would later win Grammy and Academy Awards, but it was Ring-A-Ding-Ding and his ensuing association with Sinatra that changed the course of his career.

Frank Sinatra, Irving Berlin’s ‘Be Careful, It’s My Heart,’ from Ring-A-Ding-Ding (1961), the Chairman’s first album for his own Reprise label.For the tunestack Sinatra relied on the writers whose sophistication he had long admired and relied upon: no less than three Irving Berlin songs (“Be Careful, It’s My Heart,” “Let’s Face the Music and Dance,” “I’ve Got My Love To Keep Me Warm”) were part of the repertoire, along with numbers by Cole Parter (“In The Still of the Night,” “You’d Be So Easy to Love”), Arthur Schwartz and Howard Dietz (the beautiful “You And The Night And The Music”), the Gershwins (“A Foggy Day”), Jerome Kern and Dorothy Fields (“A Fine Romance”), Harold Arlen and Fred Koehler (“Let’s Fall In Love”), Sammy Fain and Irving Kahal (“When I Take My Sugar To Tea”), and of course Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen (“Ring-A-Ding-Ding”). (Of all these, Jimmy Van Heusen was the writer who could boast the most Sinatra recordings of his songs--more than 70 tunes.) Some of these numbers Sinatra had previously recorded and was revisiting; most he was cutting for the first time. Locked away in the vaults for half a century and making its debut here is a lush treatment of “Have You Met Miss Jones,” with an evocative swirl of woodwinds and strings buttressing Sinatra’s easygoing vocal. Deemed too much the ballad for this album and thus missing the cut, its troubles began immediately: when the music starts we hear Sinatra say to Mandell, “This sounds like a different album.” Other studio chatter finds him suggesting specific points of emphasis in the arrangement. But he never quite nails it--a second take is unfolding beautifully until he stops abruptly and complains of his lyric sheet containing the wrong notes. The outtake is a little more than ten minutes’ worth of false starts and revisions, without a finished track emerging.

By all accounts (including those of 16-year-old Frank Sinatra, Jr., who was at the sessions and wrote liner notes for this reissue), the high spirits suffusing the finished product reflect the mood in the studio as well. “The recordings were made the week before Christmas,” Sinatra Jr. writes, “and the smiles on his face during those three nights left no doubt in anyone’s mind that for Sinatra, Santa Claus had come early.”

Frank Sinatra, ‘Ring-A-Ding-Ding,’ written by Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen, the title track of the Chairman’s first Reprise album, 1961.Indeed, a burst of jubilant brass introduces the album opening title track, and when Sinatra comes bouncing in he sounds lighthearted and joyous--the vocal swings with nuanced rhythmic phrasing and a carefree disposition, and without question the Chairman invests the “ring-a-ding-ding” phrase with extra-musical import. Apart from surprising Mandel flourishes such as the stop-time phrase that sends “Let’s Fall In Love” into higher orbit, the news of this album is the incredible Sinatra phrasing throughout--the studio chatter on “Have You Met Miss Jones” is indicative of how meticulous a craftsman Sinatra was, no matter how cheery and freewheeling the completed long player sounds. To fixate on what he does to coax greater feeling out of his material, to get to the essence of the songwriters’ intentions, is for all practical purposes to be humbled by the intelligence of this artistry. Witness “A Foggy Day” in which he eases back and forth between phrasing slightly behind the beat and right on the beat in a rich Mandel arrangement prominently featuring the cocktail piano of Sinatra’s long-time accompanist Bill Miller, along with a voluble, protesting muted cornet and an exuberant, sputtering horn section. Or consider the steadily rising rush of woodwinds, horns and strings propelling “In The Still of the Night” ceaselessly forward as Sinatra, cool and calm, right on the beat, cruises with the top down, in a manner of speaking, heading towards a breezy stanza at the end when the whole enterprise glides to a sexy, hushed signoff. Phrasing aside, the personality in his singing is something else again; the mood is so lighthearted he even hams it up at one point--an annoying tactic were this a darker album, but whenhe unburdens himself with a certain eager urgency in crooning the lyric “let’s leave before they ask us to pay the bill” in "Let's Face the Music and Dance," well, you gotta love being part of his good time. Ring-a-ding-ding indeed.

Two masters at pivotal points, both delivering the goods on their own terms. They won. We win.

Frank Sinatra’s Ring-A-Ding-Ding is available at www.amazon.com

Tony Bennett’s The Best of the Improv Recordings is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024