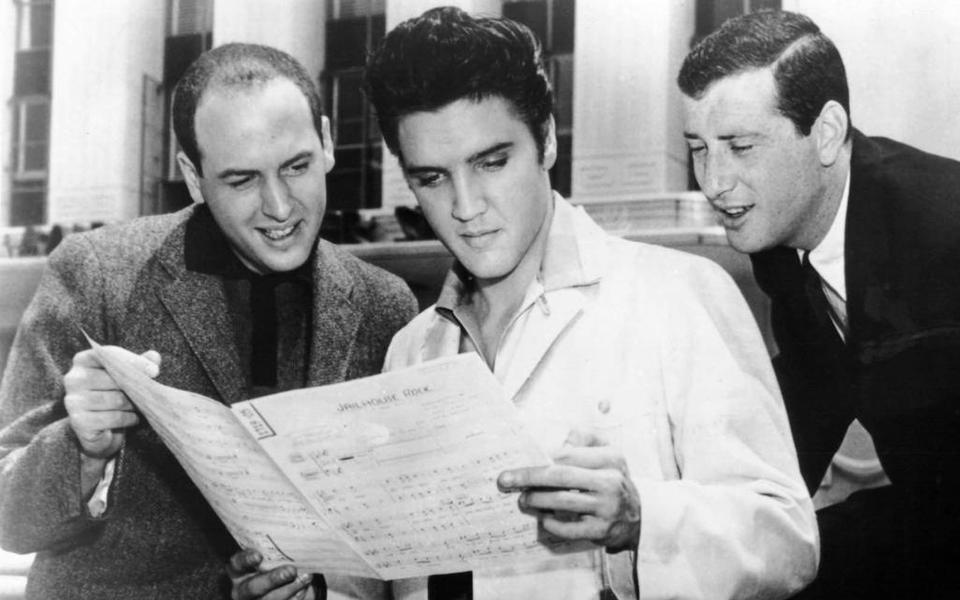

Mike Stoller (left), Elvis and Jerry Leiber check out the chart for ‘Jailhouse Rock’The Best Company In the World

A Personal Reminiscence of Jerry Leiber

By David McGee

Jerry Leiber, who along with his songwriting partner Mike Stoller (Leiber wrote the lyrics, Stoller the music and an occasional lyric), and a handful of other writers,inspired--or incited (a term Leiber would have preferred) a cultural revolution in the mid-1950s by fashioning the language of rock 'n' roll out of the language of the blues and rhythm and blues that they loved above all other music. The 78-year-old Leiber’s death on August 22 followed by two months the passing of the Coasters’ Carl Gardner, Jr., whose fame rests largely on his and his mates’ impeccable comic performances of Leiber-Stoller songs that were themselves, in the Leiber-Stoller manner, sly commentaries on both teenage miseries and the silliness of pop culture in general. Although the Coasters’ hitmaking days were over by the mid-‘60s and Leiber and Stoller had moved on from rock ‘n’ roll and even the blues to writing art and cabaret songs always with an eye towards live theater as the best venue for their new ideas, the deaths of Gardner Jr. and Leiber, coming so close together, still seem like a tolling of the bell for their era. Elvis, joined at the hip to Leiber-Stoller songs, has been gone since August 1977; the Drifters, whose soaring, string-enhanced Leiber-Stoller-produced recordings of passionate tales of urban romance by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, Ben E. King and, yes, Leiber and Stoller, were finished before the ‘60s ended. The duo’s apprentice, Phil Spector, who took the Leiber-Stoller template and built his own magnificent edifice on it, is in prison. Their wonderful Red Bird Records label, home to a string of mostly girl group hits penned by Leiber and Stoller’s trusted Brill Building friends Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Berry, existed under Leiber and Stoller’s leadership only between 1964 and 1966, when they bowed out, tired of running a business, dismayed over a fallout with their business partner George Goldner, and hungering to get back to writing and producing. The aging Baby Boomer generation that danced, loved and fought to the songs of Leiber and Stoller is fast watching its cultural moment fade from the contemporary radar: The Broadway jukebox musical version of The Million Dollar Quartet is a distortion of the actual Million Dollar Quartet impromptu gathering at the Sun studio for the twin purposes of surveying the Hit Parade of rock 'n' roll's first era and profiting from it; far less successful and equally if not more distorted in its history, the Shirelles-centric Broadway musical Baby, It’s You, from the same writers who gave us The Million Dollar Quartet, was a big bomb (and generated a lawsuit by the founder of the Shirelles’ label over the way she was portrayed in the show). In New York City, the oldies radio station WCBS-FM returned from the dead a couple or so years ago trumpeting its new format as being songs from “the ‘60s, ‘70s and ‘80s”—you can listen for hours without ever hearing a song from the ‘50s, which is pretty much true of all the oldies radio stations in America these days. The mainstream music press is now dominated by a generation of writers who seem to believe rock ‘n’ roll began with punk in the mid-‘70s and who are shockingly ignorant of all but the best known of the R&B and soul pioneers (witness a New York Times concert review of bluegrass phenom Sierra Hull this past spring, when the same critic that had dissed Elvis’s 27-CD box set in December with an insulting, uninformed review identified Ms. Hull’s cover of “You Can Have Her” as “a Johnny Rivers song.” It is only a Johnny Rivers song if you completely ignore the artist who first recorded it and had a #6 R&B/#12 pop hit with it, the great R&B singer Roy Hamilton (one of Elvis’s favorite artists, by the way). Hamilton’s record was released in 1961; three years later, in 1964, Johnny Rivers did indeed record “You Can Have Her”—as a non-single album track on his debut LP, At the Whisky à Go Go. A citation of it as “a Waylon Jennings song” at least would have recognized the only other artist to have a major hit with it, as a #7 country single in 1973. But "a Johnny Rivers song"? Do tell.).

From every perspective but one, the world Leiber and Stoller created and nurtured in their multiple roles as producers and songwriters is fast passing from memory and, it seems, from reliable history. The music stands inviolable, unassailable, and as fresh and smart as it sounded when new. On that count Leiber and Stoller will never be silenced, any more than will their achievements be diminished by future revisionist historians--what they did, and the artists with whom they did it, is so important that only the music historian equivalent of a Holocaust denier could disparage or ignore their resume, or assert that everyone else has pretty much been wrong about Leiber and Stoller from time immemorial.

The Drifters, with Ben E. King singing lead on ‘There Goes My Baby,’ a pop-R&B hybrid produced by Leiber and Stoller that employed a five-piece string section, a regular rhythm section and used a South American baion rhythm. Despite the misgiving of Atlantic head Ahmet Ertegun and Jerry Wexler over the use of strings in a nominally R&B record, ‘There Goes My Baby’ peaked at #2 on the Billboard singles chart in mid-1959.I don’t know why Jerry Leiber and I got along so well, he being a street-savvy, tough kid from Baltimore, me at the time we met a rather naïve college grad fresh off the plains of Oklahoma. He and Mike respected my knowledge of their work, though--the first time I interviewed them, in 1974, Mike turned to Jerry after my first few questions and said, “He knows more about us than we do” in what was a truly humbling moment for your faithful friend and narrator; I was even more humbled when they started plying me with ice-cold Coke in those real smoked bottles. A treasured friendship with Jerry developed from our first meeting. We would run into each other at industry events, occasionally in a club (Jerry didn’t seem much interested in clubbing--this was in the mid-‘70s--even though he was well hooked into the current musical trends), and a lot over the phone. He would call me at my Record World office to talk about an artist he was interested in writing for and/or producing, and frequently invited me over to his and Mike’s Brill Building office to listen to a new demo of an artist they were working with.

I spent enough time with Jerry to appreciate how sharp his mind and wit were, and to admire, even be inspired by, the breadth and depth of his interest not only in music but in all the arts, and in current events--he always wanted to be in touch with what was driving the culture and the politics of the day. It was all material, and the writer in him was soaking it up. I can’t say I ever knew what his politics were, except I assumed he leaned left and liberal. I have no recollection of him ever taking politicians very seriously, although I can say with authority--because he said so to me-- how happy he was when Nixon resigned.

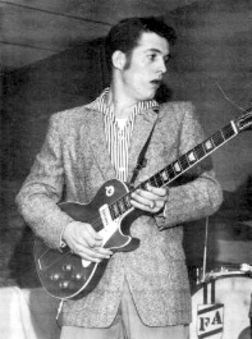

Clyde StacyI remember him questioning me closely about country and gospel music, because he knew I had grown up with and around those styles, and he hadn’t. He had some limited exposure to country and southern gospel via the radio in his parents’ home, but he wanted to hear what it was like actually to see Bob Wills, to see Patsy Cline. Here was a guy who hung out with Elvis and he thought I was cool because as a lad I had stood in front watching what were for him mythological figures. One day I brought him a tape I had made of a 45 single in my collection, a record by an obscure Oklahoma-born, Texas-raised rockabilly artist named Clyde Stacy and his band The Nightcaps, on Candlelight Records. In our part of the country, in 1957, Clyde had a double-sided hit with “Hoy Hoy” and its steamy B side, “Too Young,” the latter boasting a moaning female so unabashedly horny she made the panting on Gene Vincent’s controversial “Woman Love” seem comical. “Hoy Hoy,” on the other hand, was raw, frenzied, searing rockabilly, a classic of the genre (it did manage to get into the lower 60s of the Billboard singles chart in ’57 and cracked it again at #99 in 1959). My father had bought the record for me from the man replacing it on the jukebox in his Skid Row restaurant in Tulsa; moreover, I had seen Clyde Stacy perform on Dance Party, a Saturday afternoon American Bandstand-style show that emanated from the Oil Capitol’s Channel 6 studios downtown. Jerry was amused by “So Young”--he asked if I had the phone number of the moaning girl, and got a kick out of a bass singer mumbling softly in the background, “oh, yeah, oooohh, yeah…” But he was absolutely over the top about Stacy’s performance on “Hoy Hoy.” “You actually saw this guy?” he said, astonished. After we’d listened to the song three or four times, he opined as to how he wished he and Mike had known about Stacy back then. Said Jerry: “We knew how to write for a guy like that. He would have been a star. There’s a great artist in there.”

Clyde Stacy, ‘So Young’--Jerry Leiber wished he had the girl’s phone number

Clyde Stacy, ‘Hoy Hoy’--Jerry Leiber wished he could have written for himI think Jerry appreciated the grittiness of Stacy’s singing--there were hints of a good country blues singer in his attack--and knew instantly what the artist could have done with a certain streetwise lyric. He and Mike were uncannily attuned to the language of the street and of the penthouse alike. And it wasn’t as if one was street and one was penthouse--their sensibilities in these areas overlapped and embraced theater, literature and film, all of which provided fuel for their later work. Leiber and Stoller signaled their evolution as writers most dramatically in 1969 when Peggy Lee had a #11 pop hit with their wry, cynical “Is That All There Is?” Inspired by Thomas Mann’s novella Disillusionment and originally intended for a musical version of a play by Jeff Weiss titled The International Wrestling Match, “Is That All There Is?” was first performed by Georgia Brown in 1966, on British TV. 1966--the last year the Drifters ever had a Top 50 single, when Johnny Moore was singing lead. Leiber and Stoller were by then already off another tangent, into a more sophisticated lyrical and musical framework. Much as Doc Pomus bowed out of writing rock ‘n’ roll hits and in his later years concentrated on expressing himself in blues and blues-based songs that better reflected the feelings of an older, experienced adult “stumbling through the night like everyone else,” Leiber and Stoller’s combined sensibility was perfectly adapted to update their teen playlets into complex, and darker, adult scenes of conflict, sorrow, fleeting joys and abiding cynicism--the scales had fallen from “Charlie Brown”’s eyes in the world weariness of “Is That All There Is?”

Peggy Lee in a 1969 live performance of Leiber and Stoller’s ‘Is That All There Is?’For Peggy Lee they later wrote and produced an entire album of cabaret-intimate discourses freighted with derisive humor, uncertainty and disillusionment, titled Mirrors. It wasn’t a hit, and upon its release in 1975 many critics didn’t know what to make of either the songwriters or Miss Peggy herself, but Mirrors has grown in critical stature over the decades to where it is now regarded as approaching masterpiece status. Three years later classical pianist William Bolcom and mezzo-soprano Joan Morris collected some of the Mirrors songs, grouped those with a few more recent but obscure L&S songs, threw in the duo’s Top 10 1955 single written for The Cheers, “Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots” (L&S’s 1954 song for the Cheers, “[Bazoom] I Need Your Lovin’,” was one of the first rock and roll hits by a white group, preceded only by the Chords and Bill Haley in that distinction) and released their own arty vocal and piano interpretations on a Nonesuch album titled Other Songs by Leiber & Stoller.

Bolcom’s liner notes for Other Songs by Leiber & Stoller speak to the deep roots of Leiber and Stoller's work:

“‘Ready to Begin Again’ is a portrait of the title character in Jean Giraudoux’s The Madwoman of Chaillot. ‘Humphrey Bogart,’ a spoof of movie idolatry (expressed among 1960s poets and painters in works like John O’Hara’s To the Movie Industry in Crisis and Warhol’s silkscreen versions of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor), and ‘I Ain’t Here,’ the song of a black domestic working in a white middle-class home, are both intended for forthcoming Broadway productions.

“The other songs heard here are all theatrical in nature. ‘Let’s Bring Back World War I’ shows the influence of Barbara Tuchman’s The Proud Tower, a history of the years before that war. Leiber and Stoller have dedicated that song ‘to Joan Morris and William Bolcom.’ The writers characterize ‘I’ve Got Them Feelin’ Too Good Today Blues’ as being ‘as simple and straightforward a song of joy as Jerry Leiber is capable of writing.’ ‘Tango,’ ‘provoked’ (their word) by Ramon Navarro’s obituary in the Los Angeles Times, depicts a murder. ‘I Remember’ is a study in lyric and musical economy. ‘Black Denim Trousers and Motorcycle Boots’ was a top-10 record by The Cheers; a send-u of a Hell’s Angels-type character, it was recorded again in 1956 by Edith Piaf (as ‘L’Homme à la moto’), in an almost word-for-word French translation. Soon after her introduction of the song at Paris’s famous cabaret-theater L’Olympia, it became the Number One hit in France. ‘Professor Hauptmann’s Performing Dogs,’ perhaps the most cabaret-inspired of all the songs on this album, is described by Leiber and Stoller as ‘a parable of life in a totalitarian society,’ and reflects the sardonic political humor of the cabaret theaters of Berlin, Vienna, and Paris.”

Edith Piaf, ‘L’Homme à la moto,’ the French version of Leiber and Stoller’s 1955 song ‘Black Denim Trouser and Motorcycle Boots,’ a #6 pop hit for The Cheers in America that went to #1 in France in Piaf’s word-for-word French translation.Leiber and Stoller’s theater ventures were mostly stillborn, save for the songs. Yet they left their mark on Broadway, with 1995’s Smokey Joe’s Café, the Great White Way’s first hit “jukebox musical,” which has begat many children, some vagrants that were deservedly rushed off to detention (anyone remember Good Vibrations?), some that have grown to be champions (Mamma Mia, Jersey Boys) of a genre that has changed the Broadway musical, not necessarily for the better.

Writing in the New York Times ArtsBeat blog on September 1, Jack Viertel, senior vice president of Jujamcyn Theaters, recalled working with Leiber on Smokey Joe’s Café and what he learned about the man whose early songs, Viertel admitted, had shaped his own childhood. Say what you will about Smokey Joe’s Café as a concept, but when Viertel describes Jerry Leiber I remember the man I knew too.

He was a man with an original mind, much influenced by growing up poor in his father’s corner grocery. Given the fortune he had amassed by the time I met him, he was also amazingly work-averse, so we ended up doing “Smokey Joe’s Café” instead of any of those other shows. (With other collaborators Mike later wrote “The People in the Picture,” which was on Broadway last season.)

For “Smokey Joe’s,” the songs were already written. And they were the songs that I loved. The show was named for a relatively obscure one that ended up barely represented in the final version. Jerry liked the name for the show, though, because, he said, “it sounds like the title of something.”

Jerry saw himself very much as a descendant of the vaudeville tradition--a Jewish comedian, though not a performer himself. He and Mike invented the Coasters, an African-American group with hipster sensibility and virtuosic comic timing. Jerry and Mike not only provided the punch lines, set perfectly to irresistible music, they turned the recording studio into a mini-theater that owed as much to radio drama (and comedy) as to more traditional songwriting. “Other people wrote songs,” Jerry said on many occasions. “We wrote records.”…

Indeed, the Leiber-Stoller records were unique, combining sound effects, a raw, punctuated sound, and role-playing performers who delivered perfectly worked out two-and-a-half minute routines.

He was restless and hip, smart and tough, and--though he covered it well--sentimental in spots. He had one brown eye and one green one, and when he cocked his head and looked up at a certain angle, you knew he’d had an idea, because those eyes would brighten. No one ever knew what would come out of his mouth in those moments, which made him, right then, the best company in the world.

The best company in the world--what’s true of the man is true of his songs. No one’s dying here.

The Searchers’ version of Leiber-Stoller’s ‘Love Potion No. 9,’ originally recorded in 1959 by The Clovers, was a #3 hit in the U.S. in 1965. Some radio stations banned the Clovers single over the male singer’s reference to kissing a cop at 41st & Vine.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024