As a new season kicks off, the football world is minus four greats

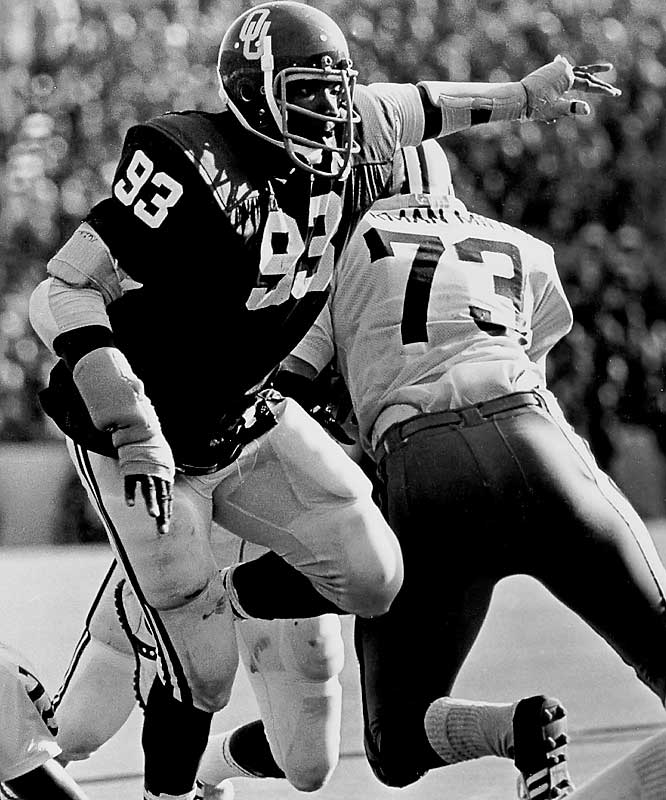

Lee Roy Selmon as an Oklahoma Sooner zeroing in on an unfortunate runner: ‘There was a sense of awe every time you were in Lee Roy's presence, and yet that was the last thing he would have wanted,’ says Oklahoma head football coach Bob Stoops‘The Rock of Our Family’

Stroke Claims NFL, College Hall of Famer Lee Roy Selmon

‘Lee Roy possessed a combination of grace, humility and dignity that is rare’—Barry Switzer

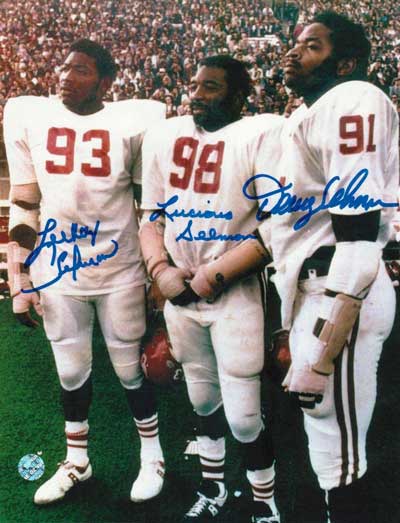

After his death from a massive stroke was erroneously reported on Twitter on Saturday, August 6, Lee Roy Selmon, the pro football Hall of Fame defensive end for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers (he was, in fact, the Bucs' first-ever draft pick) who teamed with his older brothers Lucious and Dewey at Oklahoma to create a dominant defensive front that helped lead the Sooners to consecutive national championships, died on Sunday, August 7, at age 56.

A statement released on behalf of his wife Claybra said he died at a Tampa hospital surrounded by family members.

"For all his accomplishments on and off the field, to us Lee Roy was the rock of our family. This has been a sudden and shocking event and we are devastated by this unexpected loss," the statement said.

Selmon was hospitalized on August 5, and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers confirmed later that he had suffered a stroke.

"No Sooner player cast a longer shadow over its rich tradition than Lee Roy," said Selmon's former Oklahoma coach Barry Switzer in a statement. "Beyond his many and great accomplishments, I believe the true legacy of Lee Roy Selmon lies within the kind of man he was. Lee Roy possessed a combination of grace, humility and dignity that is rare. His engaging smile and gentleness left you feeling blessed to be in his presence. Best of all, he was all genuine. One would be blessed to have a father, son, uncle, brother, or friend like Lee Roy Selmon."

Current OU head coach Bob Stoops saw in Selmon the model player who made positive contributions off the field as well and never strayed from the solid values he had been raised with.

"There was a sense of awe every time you were in Lee Roy's presence, and yet that was the last thing he would have wanted," Stoops said. "He accomplished so many things in life, but remained a humble, unassuming champion. I hold up many of our previous greats as examples for our current players and Lee Roy is among the very best. All of our players would do well to follow in Lee Roy's footsteps."

A 2010 radio interview with Lee Roy Selmon, in which he discusses playing college ball with his brothers, going to the same pro team as a rookie with one of his brothers, life in the NFL trenches and the matter of penalizing players for violent hits.While they were students at Oklahoma, Lee Roy (the youngest of the Selmon brothers), Lucious and Dewey were not only star football players but also the most popular men on campus, beloved as much for their humility, friendliness, unflagging work ethic and dedication to family as for their gridiron feats. They brought honor to themselves, their parents, their university and their state.

At Oklahoma Lucious became an All-American and three-year starter. Following their brother to the Norman campus, Dewey and Lee Roy both skipped the freshman squad to play varsity football their first season. Lee Roy and Dewey achieved All-American honors in 1974 and 1975, when Oklahoma won back-to-back national championships. Lee Roy also won the Outland and Vince Lombardi trophies in 1975. All three brothers were also accomplished students, and Dewey eventually attained a doctorate in philosophy.

After college Lucious played in the World Football League for the Memphis Southmen. After one season he returned to OU as an assistant coach. In 1995 he left the Sooners and became the linebackers coach for the National Football League's Jacksonville Jaguars.

The Tampa Bay Buccaneers selected Lee Roy as the first pick of their new franchise and the first selection in the 1976 National Football League (NFL) draft. While Lee Roy was with the Buccaneers, the league named him All-Pro six times, and he became the first Tampa Bay player to have his number retired. For thirteen years he held the club's team record for quarterback sacks (78 ½) before Warren Sapp broke it in 2000. In 1986 Lee Roy retired from football because of a back injury. Two years later he was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame. He also became the first former OU football player to be elected into the NFL Hall of Fame. Presented by brother Dewey, Lee Roy said it was his family background that was noteworthy and not his accomplishments on the field.

"People have said, 'Your parents must be proud of you,' but I'm more proud of them," he said."The guy just worked as hard as you could ever work and was just a great guy," said former Tampa Bay teammate Bill Kollar, now the Houston Texans' assistant head coach and defensive line coach. "Never got mad, was just always great to everybody and it's hard to imagine that you could end up being a better person than Lee Roy was. Really, the guy was just a phenomenal person. It's obviously really a sad day. The guy was a great player and even a better person. It's just a shame that this happened to him."

NFL Films Top 100 Greatest Players: #98—Lee Roy SelmonSelmon played a key role in the creation of the football program at South Florida, where he was hired in 1993 first as associate athletic director before promoting him to athletic director in 2001, a post he held until stepping down for health reasons in 2004. In 2000 he opened Lee Roy Selmon's restaurant in Tampa, Florida, where an expressway named in his honor.

“Here’s a guy that was from Oklahoma, who came here as a first-round pick and wasn’t from Miami, Florida or Florida State,” said St. Petersburg Times sportswriter Rick Stroud, “and as one person told me, ‘He played nine years and they named an expressway after him when his career was over, and nobody argued that it shouldn’t be named after Lee Roy Selmon. That’s the kind of impact that the man had and continued to have, spearheading the effort to start football at the University of South Florida. His contributions are endless, and at 56 years old he died way too young. The community is very saddened and their prayers go to the Selmon family and friends.”

In the second round of the 1976 draft Tampa Bay selected Dewey, making the Selmon brothers the first two picks of their organization. Dewey played for the Buccaneers until 1982, when the team traded him to the San Diego Chargers. After one year with the Chargers Dewey returned to Norman and worked as an oil and gas consultant. He served on the Norman Housing Authority board, and in 1993 he opened his own construction business.

In 1988 the Selmon brothers began marketing their Selmon Brothers Fine Bar-B-Q Sauce. Their older brother, Charles, developed the sauce for his Selmon Brothers Bar-B-Q restaurant in Wichita, Kansas, where his other brothers Chester and Elmer also lived.

The Glazer family, which owns the Tampa Bay franchise, released the following statement mourning Lee Roy: "Tampa Bay has lost another giant. This is an incredibly somber day for Buccaneer fans, Sooner fans, and all football fans. Lee Roy's standing as the first Buc in the Hall of Fame surely distinguished him, but his stature off the field as the consummate gentleman put him in another stratosphere."

While accompanying the South Florida football team to a game against Oklahoma in 2002, Lee Roy said he was humbled that Switzer had called him his greatest player.

"I see myself as just having been a teammate with so many great players and coaches," he told The Associated Press. "I'm floored by such a generous compliment."

Born Oct. 20, 1954, in Eufaula, Okla., to Jessie and Lucious Selmon Sr. and raised on a farm with eight siblings, Lee Roy and his two older brothers almost signed with Oklahoma’s Big Eight rival, Colorado. Only a last-minute recruiting effort by Oklahoma’s then-defensive coordinator (soon to be assistant head coach) Larry Lacewell persuaded them to attend OU.

In his book Wish Bone Lacewell revealed that the Sooners didn't decide to recruit Lucious Selmon until Barry Price switched his commitment from Oklahoma to Oklahoma State the day before signing day. Lacewell showed up at the Selmons' house to find Colorado coach Eddie Crowder there. When he got his chance to talk to the family, he stayed at the house until the two younger brothers had fallen asleep and he had convinced the Selmon parents it was better for Lucious to play 100 miles away than 600.

News of Lee Roy Selmon's stroke had already spurred tributes to Selmon on Saturday, August 6, when members of the University of South Florida's football team wore his number on their helmet.

"We all loved him, and we're all deeply saddened," USF President Judy Genshaft said. "We're a better university because of Lee Roy Selmon. He was an incredible role model, who cared about all of our student-athletes, no matter what sport. He built an incredible legacy and he will never be forgotten."

***

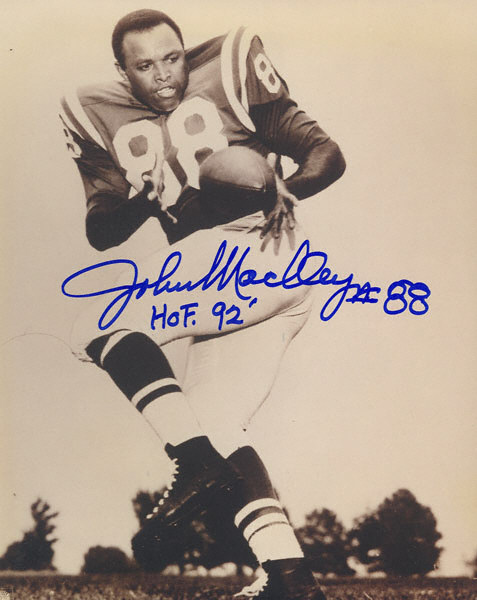

‘You can’t teach that, you can’t coach that. God pre-ordains that, and John Mackey ran with that.’

John Mackey

September 24, 1941-July 6, 2011

On July 6 came word that the great Hall of Fame tight end John Mackey had succumbed to frontotemporal dementia at age 69 while confined to an assisted living facility, where he had been for the last four years of his life. During his ten-year career, spent mostly with the Baltimore Colts, Mackey revolutionized the tight end position and, as president of the NFL Players Association after the AFL-NFL merger, fought to improve players' pension benefits and access to free agency. Mackey filed and won an antitrust lawsuit against the NFL that eliminated the so-called "Rozelle Rule," named for then-commissioner Pete Rozelle, which mandated equal compensation for teams that lost free agents and had the effect of limiting free-agent signings. The ruling set the stage for the players' union to eventually achieve full free agency.

PBS NewsHour report on John Mackey’s life and legacyUpon his dementia diagnosis the NFL Players Association initially refused to pay a disability income due to the then-unproven link between brain injury and playing football. Ultimately both the Players Association and the NFL itself came around, adopting the “88 Plan,” named after Mackey’s uniform number, which provides $88,000 annually for nursing home care and up to $50,000 annually for adult day care.

In 2010, Mackey’s wife, Sylvia, pledged to donate her husband's brain upon his death to a Boston University School of Medicine study of brain damage in athletes. The university's Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy is researching potential links between repeated concussions and CTE, a condition that mirrors symptoms of dementia and Alzheimer's disease.

Mackey played 10 seasons for the Baltimore Colts and San Diego Chargers, catching 331 passes for 5,236 yards and 38 touchdowns. Elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1992, he was the second tight end (after Mike Ditka) inducted. He played in five Pro Bowls and was a three-time All-NFL selection at his position.

Drafted in 1963 from Syracuse, Mackey, at 6-foot-2 and 224 pounds, helped revolutionize the position of tight end by bringing the added dimension of speed, forcing defenses to account for him not only as a blocker but also as a breakaway threat.

"Previous to John, tight ends were big strong guys like [Mike] Ditka and [Ron] Kramer who would block and catch short passes over the middle," former Colts coach and fellow Hall of Famer Don Shula told The Baltimore Sun. "Mackey gave us a tight end who weighed 230, ran a 4.6 and could catch the bomb. It was a weapon other teams didn't have."

‘You can’t teach that, you can’t coach that. God pre-ordains that, and John Mackey ran with that.’--A fan’s tribute to John Mackey. Great footage. At the 2:34 mark watch as Mackey takes a short pass and bulls through five Lions tacklers en route to the end zone in what has been voted the NFL’s #1 All-Time Play. Posted at YouTube by rayj2988If Mackey did not run past defenders, he ran through them. "Defensive backs fell off of him like gnats," his Baltimore Colts teammate Jerry Hill told the Sun. "John didn't have a fluid gait--he looked like a plow horse--but you didn't want to touch him for fear of getting caught up in the wheels."

"Sometimes you had a sense that, given the option, John would rather run over you than outrun you," noted former Colts teammate Bob Vogel.

"John was a tough physical specimen, an unbelievable ballplayer and a good, good man," said Lenny Moore, the Colts' Hall of Fame running back and one of Mackey's closest friends. "People will never fully understand the impact he had on talks between players and owners and the stuff we were after. John unlocked those gates--no, he knocked the doors down."

With his speed, size and determination, Mackey specialized in turning the short reception into a big gain. In 1966, six of his nine touchdown receptions came on plays of 50 yards or more. His speed led the Colts to use him as a kick returner in his rookie season.

During his nine years with the Colts, the team won a Super Bowl and three conference championships. Of Mackey's 38 touchdown receptions, 13 were for 50 yards or more, including an 89-yarder against the Los Angeles Rams in 1966. That score, on the game's first offensive play, was the longest of the 290 scoring passes in NFL legend John Unitas' Hall of Fame career.

"John didn't have the best of hands," Unitas once said, "but his running ability was second to none."

1971 Super Bowl V—Baltimore Colts vs. Dallas Cowboys. John Mackey’s reception of a twice-tipped Johnny Unitas pass and subsequent touchdown run begins at the 0:25 mark.His most famous catch came in the 1971 Super Bowl, when he grabbed a twice-tipped Unitas pass—it had been deflected by Colts receiver Eddie Hinton and Dallas Cowboys defender Mel Renfro--and raced 75 yards for a touchdown in Baltimore's 16-13 victory over Dallas, a victory secured with five seconds left when Jim O’Brien kicked a 32-yard field goal.

In 1999 Syracuse University, Mackey’s alma mater (he played for the Orange from 1960-1962), named Mackey to its all-century team in 1999 and in 2007 retired his No. 88 jersey. His legacy is remembered yearly when the John Mackey Award is bestowed upon the player deemed college football's best tight end.

A fact that has escaped John Mackey biographers is that the big tight end and his wife lent financial support to an eight-piece Baltimore-based R&B group called Pockets. Produced by Verdine and Maurice White of Earth, Wind & Fire, the band released three albums on Kalimba/Columbia between 1976 and 1980, with 1977’s vibrant workout ‘Come Go With Me’ being its biggest single hit.In his July 7 NFL Nation Blog at espn.go.com, John Clayton offered a moving tribute to Mackey, its centerpiece being an anecdote about the voting for the 1992 Hall of Fame candidates:

Mackey touched me most as a voting member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Mackey was part of my favorite class. I liked the class of 1992 because it included some of the most controversial figures in the NFL at the time--Mackey, Al Davis and John Riggins.

Mackey had his detractors because he was part of a 1977 antitrust suit against the NFL seeking free agency for players. Owners controlled everything back in those days, and they didn’t take well to challenges. Mackey was fearless on the field and didn’t fear the consequences of putting his name on a lawsuit to help himself and his peers.

I was one of the youngest Hall of Fame voters at that time. Will McDonough, the former Boston Globe icon whom I modeled my career after, pulled me aside and asked me if I would help on support for Mackey, Davis and Riggins. Davis was unpopular in some NFL circles because of his many lawsuits and battles with the league. Riggins was controversial, but he was a great player.

Spurred by McDonough, I started quietly talking to voters to gauge their thoughts on these three NFL icons. The conversations, as they usually are in on- and off-the-record Hall of Fame discussions, were positive, but it was fascinating hearing some of the reasons some voters had questions about Mackey, Davis and Riggins.

I don’t know if I convinced a single voter to support Mackey, Davis or Riggins, but the results said something. It was one of my proudest moments as a voter.

Unfortunately, Mackey wasn’t able to fully enjoy the post-football life befitting of a Hall of Famer. Mackey’s death may not open a seat at the bargaining table for retired players, but his portrait should be positioned in a spot for owners and players to see--and to remember what he and others have meant to this game.

***

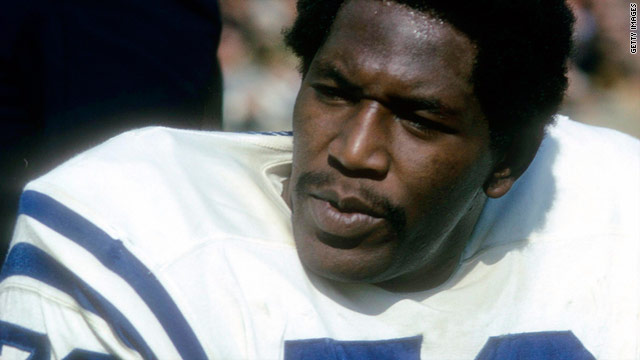

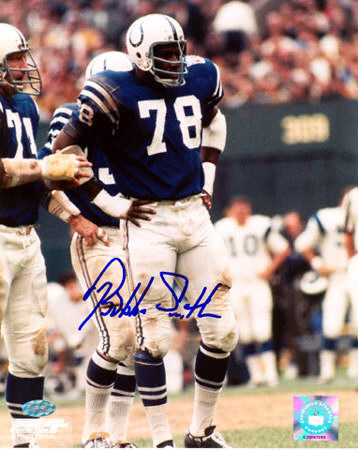

‘I just tackle the whole backfield and throw guys out until I come to the one with the ball’

Bubba Smith

February 28, 1945-August 3, 2011

More people may remember Bubba Smith less for his exploits on the football field than for his comedic turns as Moses Hightower in six Police Academy movies and various TV shows and commercials (most memorably a Miller Lite commercial, at the end of which Bubba ripped off the top of the beer can and said, “I also love the easy opening cans.”), but in his nine-year pro football career—the first five spent with the Baltimore Colts after ending an All-American career at Michigan State and becoming the first selection in the NFL draft and snapped up by the Colts—the 6’7”, 285-pound Smith was one of the biggest players of his era and one of the most ferocious. A favorite of the student fans at Michigan State, he was one of the few defensive players to merit his own chant from the crowd: “Kill, Bubba, kill!”

Smith, 66, was found dead of natural causes in his Los Angeles home on August 3.

Moses Hightower (Bubba Smith) airs it out in Police Academy 2 (1985)Born in Orange, TX, and raised nearby in Beaumont (where his father coached football at three different high schools and racked up 235 career wins), Smith was a dominant high school player with dreams of playing in college for the Texas University Longhorns. Texas coach Darrell Royal wanted to recruit Smith but the school was a member of the segregated Southwest Conference and would not buck the powers that be that prevented black athletes from playing on SWC athletic teams.

Instead, Smith matriculated to Michigan State and became even more dominant in college than he was in high school. Twice an All-American (1965 and 1966), he not only had his own chants, he was as popular a player as any of the more glamorous offensive stars of his era. In 1988 Smith was enshrined in the College Football Hall of Fame, and in 2006 his alma mater retired his #95 jersey number.

Notre Dame sits on the ball at the end of the 1966 battle of #1 teams with Michigan State, settling for a 10-10 tie. Announcers are Chris Schenkel and Bud Wilkinson.Smith’s most famous game as a college player came on November 19, 1966, when the undefeated Fighting Irish of Notre Dame came to Spartan Stadium to take on the undefeated Michigan State team. It turned into a brutal defensive struggle that produced “five fumbles, four interceptions, 25 other completions, a total of 20 rushing plays that either lost yardage or gained none,” as Dan Jenkins noted in his Sports Illustrated report of November 26, 1966, “An Upside-down Game”. With time winding down (and no overtimes in those days in the college game), the Irish offense had the ball with everyone in the stadium expecting Notre Dame, coached by Ara Parseghian, to air it out in a last-ditch effort at victory.

As Jenkins reported:

Notre Dame did not. It just let the air out of the ball. For reasons that it will rationalize as being more valid than they perhaps were under the immense circumstances, the Irish rode out the clock (see cover). Even as the Michigan State defenders taunted them and called the time-outs that the Irish should have been calling. Notre Dame ran into the line, the place where the big game was hopelessly played all afternoon. No one really expected a verdict in that last desperate moment. But they wanted someone to try. When the Irish ran into the line, the Spartans considered it a minor surrender.

"We couldn't believe it," said George Webster, State's savage rover back. "When they came up for their first play we kept hollering back and forth, 'Watch the pass, watch the pass.' But they ran. We knew the next one was a pass for sure. But they ran again. We were really stunned. Then it dawned on us. They were settling for the tie."

You could see the Spartans staring at the Irish down there. They had their hands on their hips, thoroughly disdainful by now. On the Michigan State sideline, the Spartans were jeering across the field and waving their arms as if to say, "Get off the field if you've given up." And at the line of scrimmage the Michigan State defenders were talking to the Notre Dame players.

"I was saying, "You're going for the tie, aren't you? You're going for the tie,' " said Webster. "And you know what? They wouldn't even look us in the eyes. They just turned their backs and went back to their huddle." Bubba had hollered, "Come on, you sissies," while other Spartans were yelling at Parseghian.

What Jenkins called “the biggest collegiate spectacle in 20 years--the last game to create such pre-kickoff frenzy was between Notre Dame and Army in 1946 at Yankee Stadium”—ended in a 10-10 tie. “The game was marked by all of the brutality that you somehow knew it would be,” Jenkins wrote, “when such gladiators were to be present as Michigan State's 6-foot-7, 285-pound Bubba Smith, ‘the intercontinental ballistic Bubba,’ a creature whose defensive-end play had long ago encouraged Spartan coeds to wear buttons that said KILL, BUBBA, KILL.”In his nine NFL seasons, Smith was chosen for the Pro Bowl and All-Conference teams twice. Following the 1971 season Smith was trade to the Oakland Raiders, and two seasons later to the Houston Oilers, with whom he finished his career in 1976. A Super Bowl winner with the Colts in 1970, he refused to wear his champion’s ring, saying he was embarrassed by the game’s sloppiness.

The Super Bowl ring incident was not the first time or last time Smith made a stand. When Texas would not give him an athletic scholarship owing to his race, he said the slight drove him to become a better payer in hopes his success would open doors for later generations of black players who would have the opportunities denied him.

Bubba Smith in an episode of Married, With ChildrenAfter his Miller Lite commercials brought him greater celebrity outside the football field, he was honored by Michigan State as grand marshal of a homecoming parade. As he entered the stadium where fans once chanted “Kill, Bubba, kill!” was greeted by students alternately chanting the Miller Lite slogan, “Tastes great!” and “Less filling!”

“Everyone on the stands was drunk,” Smith told newspaper columnist Scott Osler. “It was like I was contributing to alcohol, and I don’t drink.”

Smith immediately resigned as a spokesman for Miller Lite. As he explained to Ossler, he wasn’t trying to police peoples’ behavior, but he didn’t want to inspire any underage kids to start drinking.

The famous Miller Lite ‘easy opening can’ commercialAs Len Benson observed in the Deseret News of August 18, Smith “didn't make a big deal out of what he did, and of course neither did Miller Lite, and he was soon working in front of the camera again. He found a film career as the soft-spoken officer in the "Police Academy" movies and then in a number of television shows.

He was always easy to spot: He was the big guy who made you laugh.

Made you think, too.”

Benson also pointed out that big Bubba was a fount of memorable sports quotes, though these were ill-noted in all the obits and appreciations of Smith that followed the news of his death. Benson’s favorite Bubba Smith quotes:

“The whole things started when he hit me back.”

And this gem:

“I just tackle the whole backfield and throw guys out until I come to the one with the ball.”

Paying tribute to Smith in the Houston Chronicle on August 4 (“Bubba Made His Mark In Unique Way”), Richard Justice, noting that other black players—USC’s Sam Cunningham, Oregon’s Mel Renfro, SMU’s Jerry Levias (the first black scholarship football player in the SWC), who, Justice noted, “achieved greatness at SMU and handled the racial slurs and physical intimidation with such grace as to make racism look ignorant and silly”—may have had a larger hand in breaking the color barrier than did Bubba, who, though he would “answer questions about it, seemed so comfortable in his own skin that the larger message of his life didn't always get through.

Or maybe it did. He took the life that was given to him, made the most of it and worked to change what he didn't like. He played some great games, made people laugh and died with hundreds of friends. As legacies go, that's not a bad one.”

***

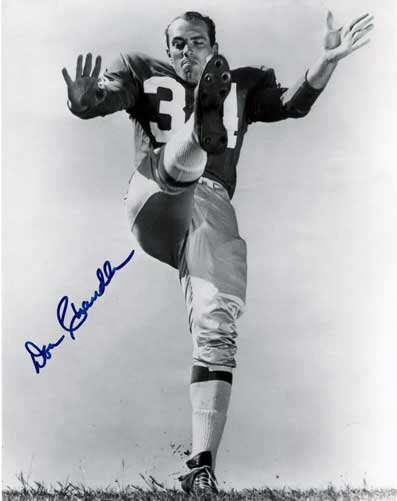

‘Sometimes I feel like the one-armed paperhanger’

Don Chandler

September 5, 1934-August 11, 2011

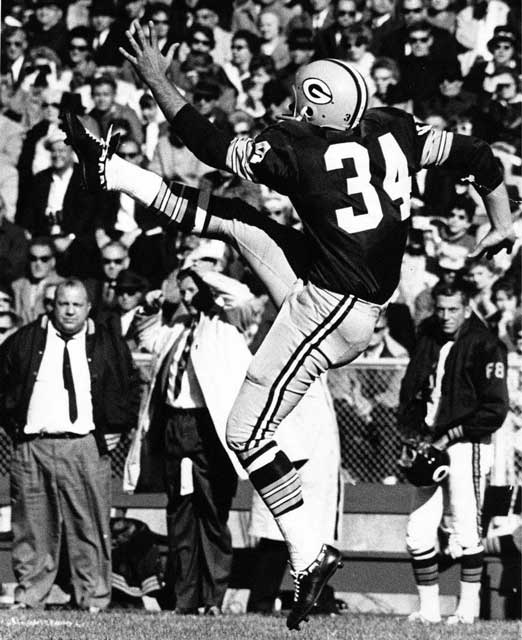

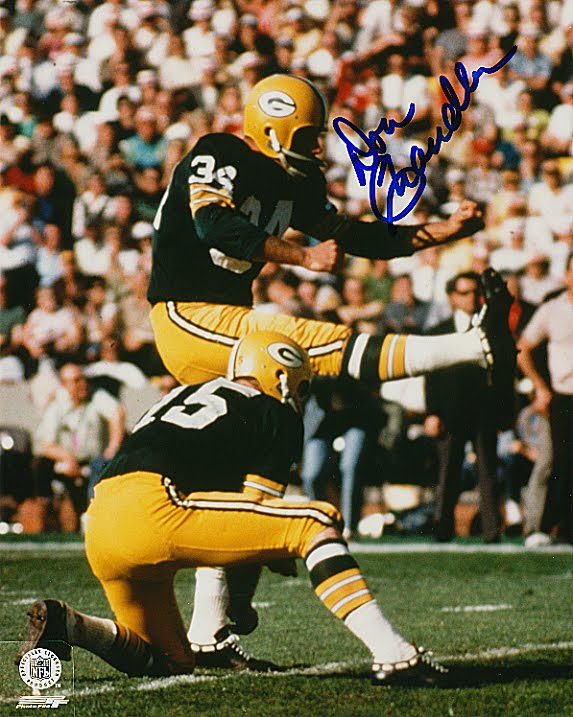

Lou Groza may have been the best-known kicker in football in a career that began in 1946 and continued through 1967 (save for two years—1960 and part of 1961—when he did not play), but Don Chandler was arguably the most important kicker in a career that overlapped Groza’s. Chandler, who played professionally from 1956 through 1967, was a key component of two outstanding clubs in his day: the New York Giants of the late ‘50s and early ‘60s; and the final three years of Vince Lombardi’s dynasty era with the Green Bay Packers, 1965 to 1967. Chandler played in nine NFL championship games (including the fabled 1967 Ice Bowl at the Packers’ Lambeau Field). But unlike Groza, or most other outstanding kickers of his time, Chandler was a force both as a punter and as a placekicker. In nine years with the Giants he averaged an impressive 51 yards per punt out of his end zone. First used by the Giants strictly as a punter (from 1956 to 1961), Chandler took over placekicking duties following Pat Summerall’s retirement. In 1963 he made 18 of 29 field goal attempts plus 52 extra points to lead the league in scoring with 106 points.

Playing before the advent of sidewinding soccer-style kickers, Chandler approached the ball straight on, wearing the standard square-toed, black high top football cleats for placekicking but changing to a low-cut shoe for punting. When the offense moved the ball into field goal territory, he would be on the sidelines changing his footwear so he would be prepared to go on the field for a possible field goal or extra point attempt. “Sometimes I feel like the one-armed paperhanger,” he told Gene Hintz in a chapter titled “Kicking” published in the 1965 Green Bay Packer yearbook. “The coach changes his mind and I have to change my shoe. The low one isn’t bad but lacing up the other takes time.”

He led the NFL in average yards per punt with 44.6 yards in 1957 and led the league with a field goal percentage of 67.9 percent on nineteen of twenty-eight attempts in 1962. Chandler still holds the record for most field goals scored in a Super Bowl with four in the 1968 Super Bowl against the Oakland Raiders, clinching the championship for the Packers.

Don Chandler was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa. He attended Will Rogers High School in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and he played for the Will Rogers Ropers high school football team.

After graduating from high school, Chandler first attended Bacone Indian College in Muskogee, Oklahoma, and then transferred to the University of Florida in Gainesville, Florida, where he played halfback, punter and placekicker for coach Bob Woodruff's Florida Gators football team in 1954 and 1955. As a senior in 1955, Chandler led all major college punters with an average kick of 44.3 yards, narrowly beating out Earl Morrall of the Michigan State Spartans. Memorably, Chandler also kicked a 76-yard punt against the Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets in 1955, which remains tied for the second longest punt in Gators history. Woodruff ranked him and Bobby Joe Green as the Gators' best kickers of the 1950s.

Chandler graduated from Florida with a bachelor's degree in 1956, and was later inducted into the University of Florida Athletic Hall of Fame as a "Gator Great."

After college, he was selected in the fifth round (fifty-seventh pick overall) of the 1956 NFL Draft, and played with the New York Giants and Green Bay Packers. He played in the first two overtime games ever in the NFL, in 1958 with the Giants against the Baltimore Colts and again in 1965 when he kicked the winning field goal for the Packers against the same Colts in a Western Conference playoff game at Green Bay. Chandler's fourth-quarter field goal that tied the game at 10-10 stirred controversy, as many Baltimore players and fans thought he missed the kick to the right. Chandler was named the punter on the NFL 1960s All-Decade Team. He went to the Pro Bowl after the 1967 season.

Chandler helped coach Vince Lombardi's Green Bay Packers teams win Super Bowls I and II. He holds the modern day record for the NFL's longest punt, ninety yards against San Francisco in 1965. He was named to the All Pro team in 1967.

In his twelve-season NFL career, Chandler played in 154 regular season games, kicked 660 punts for a total of 28,678 yards, 248 extra points on 258 attempts, and ninety-four field goals on 161 attempts. He also rushed for 146 yards on thirteen carries, and completed a perfect three passes on three attempts for a total of sixty-seven yards.

Chandler was inducted into the Packer Hall of Fame in 1975, along with tight end Ron Kramer, defensive end Willie Davis, guards Jerry Kramer and Fuzzy Thurston and Vince Lombardi. Chandler was selected as the premier punter for the decade in the 1960s. In 2002, he was named to the Oklahoma Team of the Century by The Oklahoman and in 2003 to the list of Oklahoma's Greatest Athletes by the Tulsa World. Chandler is also a member of the Oklahoma Sports Hall of Fame and the New York Giants Wall of Fame.

Chandler died of cancer at his home in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on August 11, 2011; he was 76 years old.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024