‘Here Was Something New Under The Sun’

When Bill Monroe hired Earl Scruggs in 1945, bluegrass music was forever changed…

[Ed. Note: When Earl Scruggs died of natural causes on the morning of March 28, American music lost one of its true giants—a man who so totally transformed his instrument that banjo players speak of its history as being “pre-Scruggs” and “post-Scruggs.” Born near Flint Hill, North Carolina, Scruggs was the visionary in a distinguished line of Tar Heel State banjoists. As a professional his career was marked by three distinct periods: as a member of Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys; as a popular duo act with Lester Flatt; and in the early ‘70s in the Earl Scruggs Revue, an endeavor that crossed bluegrass with a little bit of rock ‘n’ roll propulsion in Earl’s teaming with his talented sons Randy, Gary and Steve. From Bill C. Malone’s essential Country Music USA we offer the following excerpts from the author’s appraisal of each of these periods in Scruggs’s towering career.]

By 1945 much of the drive, dynamism, and timing of bluegrass music, as well as much of its repertoire, had been integrated fully into Monroe’s music. The Blue Grass Boys were already becoming famous for their fiddlers, such as Art Wooten, Tommy Magness, Howdy Forrester, and Jim Shumate, and Bill Monroe’s distinctive mandolin chop-rhythm gave the group an overall sound different from that of other country bands. But given the overriding importance assumed by the instruments in bluegrass music today, the most conspicuous omission from Monroe’s band was the five-string banjo played in three-finger style.

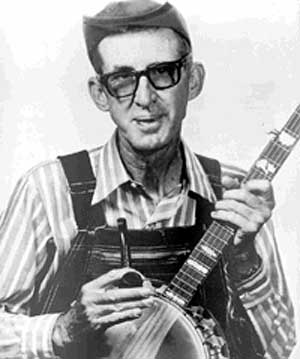

‘Stringbean’Because of wartime restrictions, the Blue Grass Boys made no recordings between October 2, 1941 and February 13, 1945. When they resumed recording, in 1945, this time on the Columbia label, their sound reflected the changes made in their performing style during the interim. Sally Forrester, wife of fiddler Howdy Forrester, played the accordion and, most significantly, David “Stringbean” Akeman, who had joined the band in 1942, played the five-string banjo. By the mid-forties the banjo was perceived as a solo instrument, most often used by comic performers such as Uncle Dave Macon, Grandpa Jones, and Bashful Brother Oswald, and when used in a band it generally played only rhythmic backup passages. Stringbean was much admired as a droll comedian, but when he quit the band in 1945 to team up with Lew Childre, his departure was not greatly mourned by the other Blue Grass Boys. Stringbean had contributed little to the overall sound of the band and had, in fact, hindered their drive by his tendency to drag the melody. But when Earl Scruggs joined the Blue Grass Boys in 1945, he brought a sensational technique that rejuvenated the five-string banjo, made his name preeminent among country and folk musicians, and established bluegrass music as a national phenomenon.

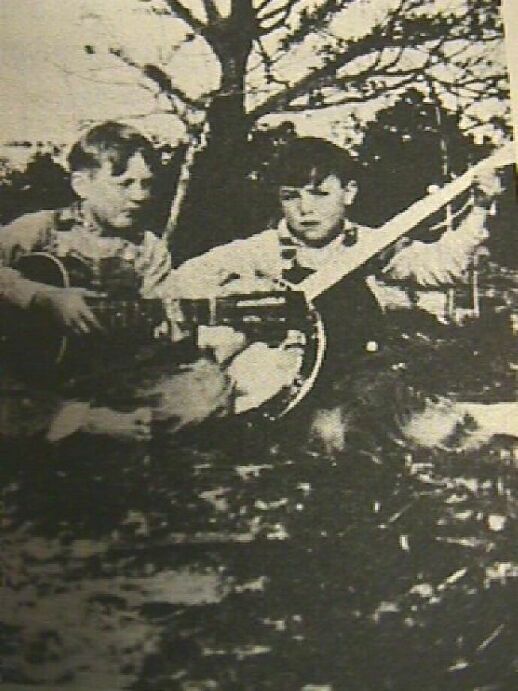

The Scruggs brothers, Horace and EarlEarl Scruggs was born on January 6, 1924, on a farm near Flint Hill, North Carolina (outside Shelby), in a region where banjo pickers thrived. His father and older brothers played the banjo in a style peculiar to their section of North Carolina--a three-finger style (thumb and index and middle fingers) which permitted the instrument to be played in a melodic, syncopated fashion. Along with these models, Scruggs was also exposed to the style through the playing of other western North Carolinians such as Mack Woolbright, Rex Brooks, Smith Hammett (a distant relative of Scruggs’), and Snuffy Jenkins. Jenkins, a product of Harris, North Carolina, had taken the technique to the largest audience through his performances on WBT in Charlotte in 1934 and on WIS in Columbia, South Carolina, after 1937. Many banjoists, including Don Reno and Ralph Stanley, credit Jenkins with having given them their first exposure to three-finger picking.

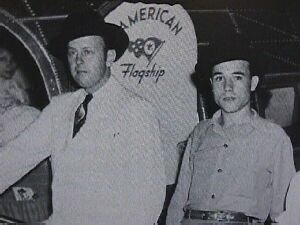

Bill Monroe and Earl ScruggsEarl Scruggs, therefore, did not invent the style which now bears his name, but he perfected it and carried it to greater technical proficiency than anyone before him. Above all, as a member of the Blue Grass Boys and later as a partner with Lester Flatt, he did the most to introduce “Scruggs picking” to the world. When he joined Bill Monroe in 1945 as an instrumentalist, the twenty-year-old musician already had several years of professional experience, including a short stint with Wiley and Zeke Morris in 1939 over WSPA in Spartanburg, North Carolina. He was part of Lost John Miller’s band in Nashville when Monroe hired him as a Blue Grass Boy in August 1945. Scruggs added a new and dynamic ingredient to the Blue Grass Boys sound, and audiences were bowled over by the boy who, with a shower of syncopated notes, had made the banjo a lead instrument capable of playing the fastest of songs. Here was something new under the sun--a banjo player who acted as a serious musician and not as a figure of comic relief. Even Uncle Dave Macon, watching from the wing of the Grand Ole Opry, supposedly said of the poker-faced young man, “He ain’t one bit funny.”

Scruggs joined a band of superb musicians which, to many bluegrass partisans, will always rank as both the first and the best in the bluegrass genre. This was classic bluegrass at its zenith. In addition to Monroe and Scruggs, this seminal band included Lester Flatt on guitar, Robert “Chubby” Wise on fiddle, and Cedric Rainwater (Howard Watts) on bass. Between 1945 and 1948 the modern bluegrass sound came into being. According to bluegrass authority Pete Kuykendall, the first recorded numbers to bear all the elements of the new style were “Will You Be Loving Another Man,” featuring the lead singing of its writer, Lester Flatt, and “Blue Yodel No. 4” (an old Jimmie Rodgers number), recorded for Columbia on September 16, 1946. Well before the records came out, however, fans and musicians had ample time to be exposed to the exciting new sound through WSM broadcasts and the popular tent show tours sponsored by Monroe. The Blue Grass Boys traveled in a nine-passenger Packard limousine with a rack on top for the bass fiddle, and with a complement of five racks which transported the tent, bleachers, and chairs. Periodically, Monroe and the boys also challenged communities to sandlot baseball games, an effective way of breaking the monotony of constant travel and of advertising the night concerts.

Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys with Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and Chubby Wise, ‘Bluegrass Breakdown’In the three-year period from 1945 to 1948 the banjo assumed a prominence in Monroe’s music that it had never enjoyed in any previous band, and an ensemble style of music, much like jazz in the improvised solo work of the individual instruments, came into existence. Throughout the nation, largely unnoticed by the more commercial world of country music, a veritable “bluegrass revolution” got underway as both fans and musicians became attracted to the music. Young musicians began copying the sounds they heard on Bill Monroe records: the mandolin, the banjo, and fiddle passages of Monroe, Scruggs, and Wise, the guitar runs of Lester Flatt, and the high, hard harmony singing of Flatt and Monroe or of the trios and quartets featured on gospel numbers. It is no wonder that Bill Monroe felt bitterly disappointed and even betrayed, when Flatt and Scruggs left the group in 1948. His greatest band now seemed a thing of the past, and he perhaps did not realize that a host of great musicians were yearning to play for him.

Flatt & Scruggs Emerge

In 1948 Flatt and Scruggs grew tired of the Blue Grass Boys’ grinding road schedule and temporarily retired from the music business. Before the year was over, however, they had formed their own band, the Foggy Mountain Boys, named after a Carter Family song they often performed. Joined by two other recent dropouts from the Blue Grass Boys, fiddler Jim Shumate and bass player Cedric Rainwater, along with another guitarist and featured singer, Mac Wiseman, Flatt and Scruggs began the independent professional career that would soon make them one of the most popular country acts in the nation.

The original 1949 Flatt and Scruggs recording of ‘Foggy Mountain Breakdown’After working for about three weeks in Hickory, North Carolina, Flatt and Scruggs moved in the spring of 1948 to WCYB in Bristol, Virginia, where they began receiving hundreds of cards and letters and requests for bookings too numerous to be filled. In the same busy year of 1948 they recorded the first of their songs for Mercury, a body of material that still stands as among the most exciting in the history of bluegrass music. Most bluegrass bands still include songs from Flatt and Scruggs’ Mercury years (1948-1950) in their repertories: “My Little Girl in Tennessee,” “Foggy Mountain Breakdown” (made doubly famous in 1967 as the theme for the movie Bonnie and Clyde), “My Cabin in Caroline,” “We’ll Meet Again, Sweetheart,” “Old Salty Dog Blues,” “Roll In My Sweet Baby’s Arms.” The popularity of the two last-named songs seems all the more remarkable in that they were recorded more or less as filler at the band’s last Mercury recording session in October 1950, a session done in haste to fulfill a contractual obligation before moving to the Columbia label.

Johnny Cash and the Tennessee Two’s performance of ‘So Doggone Lonesome’ sets up Flatt and Scruggs’s ‘Salty Dog Blues,’ with a cameo by June Carter at the end of the clip.Flat and Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys also became one of the most active touring groups in country music, first in such “traditional” formats as store openings, drive-in movies, country schools, and county fairs, but eventually in the largest auditoriums in the nation, on college and university campuses, at folk festivals and clubs, at Carnegie Hall, and in Japan. A major breakthrough in their career came in 1953 when the Martha White Flour Mills hired them to do a fifteen-minute program on WSM each morning at 5:45. Fans came to know the Martha White jingle as well as they did other songs in the Flatt and Scruggs repertory, and the duo often received requests for the tune at their concerts. The association with Martha White Flour was mutually profitable for Flatt and Scruggs and the company. Their music was introduced to a steadily expanding public, even though the pace required to do personal appearances and then to return for the early morning radio show was a killing one (WSM eventually, and mercifully, permitted the shows to be taped.) On the strength of their mounting popularity and best-selling Columbia records, WSM added them to the regular cast of the Grand Ole Opry in 1955. This coveted forum further contributed to their growing fame, a recognition that not even the impending rock-and-roll invasion could diminish. The Martha White Company was not hesitant about expressing its gratitude to the Foggy Mountain Boys. Cohen T. Williams, president of the firm that advertised Hot Rize (a self-rising ingredient in the flour and meal), stated unequivocally that “Flatt and Scruggs and the Grand Ole Opry built the Martha White Mills.”

From the Grand Ole Opry TV show, Flatt and Scruggs perform ‘Roll In My Sweet Baby’s Arms’Flatt and Scruggs’ music communicated beautifully via the radio microphone and phonograph recordings, but to be fully appreciated it needed to be seen as well as heard. The physical interaction between the musicians, the smoothness of their performances, and the diversity of their material made the Flatt and Scruggs show both an auditory and a visual delight. Lester Flatt was responsible for much of the easy-going ambiance of the show. Ever since his birth in Overton County, Tennessee, in 1914, he had been consumed with making music; but until he joined Charlie Monroe’s Kentucky Pardners in 1943 as a mandolin player and tenor singer, the demands of an early marriage had never permitted him much respite from long periods of employment in textile mills. From the Kentucky Pardners he went directly to the Blue Grass Boys, where he gained invaluable experience as a master of ceremonies and as a lead singer (the only Blue Grass Boy in history to be identified on record labels along with Bill Monroe). As co-leader of his own band, Flatt proved to be a genial and unassuming host, a singer with a relaxed and supple style, and a backup guitarist of considerable skill. When playing songs at breakneck speed with Bill Monroe, he devised a method of getting back on the beat before resuming singing after instrumental breaks. This was an ascending run which began on the bass E string and ended with a ringing note on the third or C string. Although the run was played most often in the key of G, the use of the capo permitted it to be used in other keys, such as A or B, which were popular in bluegrass. The Lester Flatt G-run, as it has come to be called, was widely copied by other guitarists. Bass runs of this type were among the most distinctive features of bluegrass music. Played on deep-tuned acoustic guitars (usually Martin D28s), and coming at the end of fiddle, mandolin, or banjo sequences (and sometimes at the end of vocal phrases, as in Monroe’s “Uncle Pen” or Jimmy Martin’s “Sunny Side of the Mountain”), the runs added a dramatic note of emphasis or finality to the overall mood of intensity created by the supercharged music.

Many people, of course, came to hear the Foggy Mountain Boys solely because of Earl Scruggs. His dazzling banjo style was made to seem even more remarkable by the seeming ease with which he did it. He usually stood poker-faced on the stage, his body appearing almost motionless as the three fingers of his right hand produced a torrent of notes. In October 1954 he introduced still another affecting technique that added further to his reputation as a master musician. On “Earl’s Breakdown” he adjusted his tuning pegs at various intervals in the song to move from one key to another and then back to the original. By the time he recorded “Flint Hill Special” in November 1952, he had devised a tuning mechanism that permitted quick retuning of the banjo’s B and G strings. Scruggs was not content to be merely a banjo virtuoso; he occasionally picked up a guitar, especially on gospel numbers, and demonstrated a mastery of both finger picking and Carter Family-style techniques.

Flatt and Scruggs, 1964, ‘Flint Hill Special’: ‘In October 1954 Scruggs introduced still another affecting technique that added further to his reputation as a master musician. On ‘Earl’s Breakdown’ he adjusted his tuning pegs at various intervals in the song to move from one key to another and then back to the original. By the time [Flatt and Scruggs] recorded ‘Flint Hill Special’ in November 1952, [Scruggs] had devised a tuning mechanism that permitted quick retuning of the banjo’s B and G strings.’Flatt and Scruggs were more than ably supported by the talented musicians who made up the Foggy Mountain Boys. Much of the verve and drive of the band came from its fiddlers, particularly Benny Martin (who also attempted a solo singing career in the fifties) and Paul Warren. Martin had played on on the great Mercury recording sessions, but Warren, an alumnus of Johnny and Jack’s Tennessee Mountain Boys, was with Flatt and Scruggs through all the important years after 1954. A high point of each Flatt and Scruggs concert was Warren’s rendition of such hoedown tunes as “Sally Goodin” or his showpiece, “Black Eyed Susan.” Probably in an attempt to build a sound different from Bill Monroe’s, Flatt and Scruggs gave little prominence to the mandolin; instead, their mandolin players were best known for their harmony singing. Everett Lilly was a fine musician from Clear Creek, West Virginia, and he did take an occasional instrumental break. Nevertheless, his real value to the Fogging Mountain Boys came through his high, crisp tenor singing. Curly Sechler (also spelled Seckler) was even more important to the group because he remained with them for many years, during bot the Mercury and Columbia periods, and after that was a mainstay of Lester Flatt’s new group, the Nashville Grass. Sechler’s mandolin was almost never heard--in his own words he just “held the mandolin”--but his tenor harmony was unsurpassed in the whole field of bluegrass music. His powerful, ringing voice complemented Lester Flatt’s perfectly, and on such songs as “Some Old Day” and “My Little Girl in Tennessee” they gave echoes of the brother-duet style of singing, while also defining the essence of bluegrass harmony. Although the mandolin’s relative unimportance was a factor in establishing a unique identity for Flatt and Scruggs, the addition of the dobro in 1955 was much more significant. Some bluegrass purists lamented the use of an instrument that had not been present in Bill Monroe’s original band (forgetting that the master himself had once employed an accordionist), but the instrument immediately attracted the fancy of listeners and did much to give Flatt and Scruggs an entrée into the broader country and western field.

With Earl on guitar, Flatt and Scruggs perform ‘Turn Your Radio On’The dobro player was Burkett “Buck” Graves (also known in his comedian’s role as “Uncle Josh”). Graves may not have been the first dobro player in bluegrass music--Speedy Krise, for example, had played the instrument on a Carl Butler recording in December 1950--but he undoubtedly did most to revitalize it and to make it attractive to younger musicians. During earlier periods with such performers as Molly O’Day and Mac Wiseman, Graves had played the dobro in a style that was indebted to his hero, Cliff Carlisle, and to other musicians such as Bashful Brother Oswald. Graves, though, was captivated by Scruggs’ rapid, multiple-noted banjo playing, and he became determined to adapt that style, or something similar to it, to the dobro. By the time he became a Foggy Mountain Boy, Graves had perfected a rolling, syncopated style that enabled him to play galloping breakdowns as well as slow love songs or ballads. With Graves leading the way, the dobro made a major comeback in country music, and some of the old-time masters of the instrument--most notably Shot Jackson, who appeared on scores of records during the sixties--began to re-emerge from undeserved obscurity. A growing number of young musicians, such as Mike Auldridge and Jerry Douglas, also began an experimentation with the instrument whose fruits would flower frequently in the late sixties and early seventies.

The Foggy Mountain Boys did not merely play well, they also looked good while doing it. Since they used no electric instruments, they were heavily dependent on microphone amplification. Most of the places where they played had few microphones, so the musicians had to move in and out of the center stage in order to take their vocal and instrumental breaks, while also being careful not to bump into each other or to poke a fiddle bow into someone’s eye. The Foggy Mountain Boys converted a technical necessity into an art, moving to and from the microphone with a smoothness and precision that seemed choreographed. The sight of Buck Graves weaving in and out of musicians in order to lift his dobro to the microphone was something that will not soon be forgotten. The dramatic stage presence exhibited by the group, along with the skillful blending of songs and comedy (usually performed by Graves and bassman Jake Tullock as “Uncle Josh” and “Cousin Jake”), all combined to make the Flatt and Scruggs show one of the legendary acts of country music history. …

From Season 1, Episode Flatt and Scruggs visit Cousin Pearl Bodine (played by Bea Benadaret) on The Beverly Hillbillies. Clips features a rare Earl vocal on ‘Pearl Pearl Pearl.’ Flatt and Scruggs appeared on seven episodes of the show between 1963 and 1968.Flatt and Scruggs’ association with the folk movement had more mixed results. The duo reached an immense audience through this relationship and Earl Scruggs was lionized by urban folk enthusiasts. Flatt and Scruggs needed little encouragement to do old-time songs, for they had been performing such material all their lives. But they were also pressured--by their Columbia recording directors--to record contemporary material written by urban folk artists such as Bruce “Utah” Phillips and Bob Dylan, and with instrumental backing that sometimes smothered their fresh acoustic sound. This arrangement sometimes bore sweet melodic fruit, as in their popular performance of Phillips’ “Rock Salt and Nails,” but more often it resulted in listless, unimaginative renditions that seemed greatly out of character for the group. Earl Scruggs tolerated the material, partly through the influence of his musical sons, but Lester Flatt, who had to sing it, was uncomfortable with lyrics which he did not feel or, sometimes, understand. …

Enter the Earl Scruggs Revue

The Flatt and Scruggs partnership dissolved in 1969, a victim of too many years together and of differences concerning future stylistic choices. Flatt returned to his real love--classic bluegrass--and he continued to produce good music with his new band, the Nashville Grass, until his death on May 11, 1979. Scruggs formed a band with his musical sons (Gary, Randy and Steve) called the Earl Scruggs Revue. The Revue was only on the fringe of bluegrass, and Earl’s banjo was generally smothered by the heavy cacophony of sound produced by his children’s electric instruments. Earl, though, had the chance to exploit an opportunity presented to few fathers--the possibility of sharing his children’s musical experiences--and in the person of Randy Scruggs country music was introduced to one of its greatest guitarists.

Bill C. Malone and Jocelyn R. Neal’s Country Music U.S.A. (Third Revised Edition) is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024