Mark O’Connor: ‘One of the interesting things about American music is that it has this broader dimension. It kind of speaks about our time right now, looks towards the future by engaging people and reflects and remembers home. It remembers where we came from. Those are the aspects, I think, that really give voice to what Americana is all about.’TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview

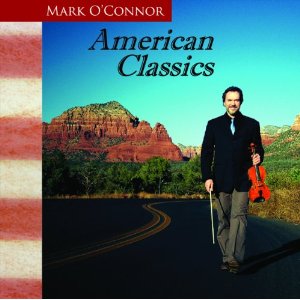

Mark O’Connor: The Simple Complexities of American Classics

By David McGee

Sometimes the simplest things hide the greatest complexities.

Consider multi-Grammy winner Mark O’Connor’s new album American Classics, for instance. On first blush it seems yet another of his career-long explorations and examinations of the many strains of music that have defined both this country’s melting pot character and his musical identity. So he gives us not only the jubilance of “Rubber Dolly Rag” and “Boil ‘em Cabbage Down,” but also the evocative, lilting beauty of the Mexican tune “Over the Waves”; the compelling sentimentality of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home”; the buoyant ragtime of Scott Joplin’s “The Entertainer”; the jubilance of the Canadian tune “Rippling Water Jig”; his own languid, summery blues, “In the Cluster Blues”; a lively “Hava Nagila”; the traditional Irish fiddle tune “Herman’s Hornpipe” (aka “Uncle Herman’s Hornpipe”) that dates back at least to the 1700s but was embraced and became identified with the great Texas fiddler Benny Thomasson (one of O’Connor’s heroes). Masterfully executed by O’Connor on violin accompanied only by the stellar native Japanese pianist Rieko Aizawa, those largely iconic tunes represent, to quote from O’Connor’s own liner notes, “’our’ collective language created in the melting pot of America by the interconnecting of immigrant cultures from Europe, Africa, Latin America, the Middle East and Near Asia. Our blues, gospel, rags and hoedowns, popular songs and jazz are the wellspring of this collective spirit of people from all over the world living in America and making music together.”

It is that, to be sure. It is also an aural guide through the forthcoming Book 3 of the O’Connor Method, which will be published this summer complete with two CDs--this one with O’Connor and Ms. Aizawa in tandem, and another with the pianist alone, so students can play the tunes to her accompaniment. Music education has long been an O’Connor focus: the Method is merely the culmination (although it is far from complete) of a commitment the string master made some 17 years ago when he launched the first of his comprehensive summer string camps for players of varying degrees of accomplishment, from beginners to pros, from first-grade and older, with instruction provides by O’Connor himself and a staff of guest instructors boasting impeccable credentials in their specific disciplines. As an example, the O’Connor Berklee College Summer 2012 String Program, slated for June 25-29, features no less than 25 violin instructors (including the likes of Buddy Spicher on country and western swing, Matt Glaser on bluegrass fiddle, Sara Caswell on jazz, Berklee faculty member Oisin McAuley on Irish fiddling and Daniel Bernard on hip-hop and rock violin), as well as instruction in viola, cello (Ben Sollee is one of the instructor), bass, mandolin (with Sarah Jarosz instructing), and five instructors teaching the O’Connor Method.

Understanding anything about Mark O’Connor begins with appreciating the role education has played in his own life and career. In his youth the Seattle, Washington-born O’Connor was mentored by the aforementioned Benny Thomasson, by the legendary French jazz violinist and Django Reinhardt partner Stephane Grappelli, and by the equally legendary Chet Atkins, whose versatility seems a model for O’Connor’s own eclectic path. In his teens O’Connor won national titles on the fiddle (age 13--the Grand Masters Fiddle Championships; age 14--the National Flatpick Championships); age 19--the Buck White International Mandolin Championship), and between 1979 and 1984 he won four grand championships at the National Oldtime Fiddlers Convention.

O’Connor was fortunate to be playing at such a high level that the likes of Benny Thomasson and Stephane Grappelli would take him under their wings. What he learned from them was not taught in schools, but by the time his first string camp came around music instruction--indeed, music education--in public schools in the U.S. was a thing of the past.

As the attendance at his camps swelled, O’Connor formulated his ideas for a new string method that would offer a different perspective than that of the long established Suzuki, Essential Elements and American Fiddle Method. As he explains on his website: “I have written a violin method. Not a fiddle method. While fiddle tunes make up a portion of American music, it certainly does not represent the entirety of it. And what I am featuring in the new method is music of the Americas (music from the U.S, Mexico and Canada). The concept is that a child can learn how to play the violin and other string instruments without having to completely ignore American music as the other violin methods do. While American music essentially is derived of music from Europe, Africa, South America, Near Asia, and the Middle East, I feel it to be an inclusive method inherently.”

He adds: “There a several features of my new violin method that differentiates itself from many other violin methods. I went to great lengths to find beginning repertoire that represented literature that was historic and possessing a timeless quality, music that is played professionally to this day and not merely children's music or exercise tunes. I include a creative component in the method that allows for individual creative growth as a composer and improviser. There is a ‘green’ component to the book, tying in the importance of the natural habitat, American music inspiration and childhood learning together. Perhaps most important of all, American music represents music developed by cultures and ethnicities from around the world. A significant portion of the violin method contains material written and developed out of African American, European American and Latin American communities, and much of it cross pollinated between these communities dating back to 400 years ago with one of the first known American styles, the ‘Hoedown.’ More communities including the Native Americans and the first Appalachians including the Turkish and Middle East populations also had a lot to do with establishing the language of the music. I also include text about the rich histories of much of the music to provide relevance.”

Mark O’Connor, age 13, plays ‘Tom and Jerry’ on The Porter Wagoner Show (1975)

Mark O’Connor, age 23, with Eddie Davidson on guitar, performs ‘Tom and Jerry’ on the TV series Down Home.Always, he returns to music as it reflects the American character, to wit, when discussing how to teach a student one-on-one how to improvise: “Students can realize in my method that there are choices that they can make about certain aspects of the musical material, and they can act on these choices individually, and change the music towards their own perspective. This creates the feeling of thinking outside the box, of ingenuity, which is the backbone and spirit of not only American music but of the American individual. The American musical system is at one with our culture here, our cultural DNA taps into this music, the phrases, the rhythms and the vocabulary. It is a way of life we know in this country; our music reflects that rugged individualism.”

Thus one of the extra-musical applications of American Classics. To get lost in the album is to experience it on a whole other level. However much it might be designed as an academic exercise, this is, after all, a Mark O’Connor project, which means the high caliber of musicianship serves the greater purpose of plumbing the innermost soul of his material, whether original or borrowed. Much as life sprung from the strings of Benny Thomasson and Stephane Grappelli, so does it infuse O’Connor’s playing--he always gets to the heart of the matter.

Allow your feelings to follow the music’s flow and you find the tranquility of American Classics draws you in, embraces you, speaks to you. The beauty of the melodies, the graceful rhythms and Ms. Aizawa’s textured responses to O’Connor’s soulful expression, which in turn carries the weight of the ages. Look no further than “Deep River,” a “sorrow song” back in the days of slavery before those tunes were called “spirituals.”

From American Classics, ‘Deep River,’ Mark O’Connor and Rieko Aizawa: ‘an unambiguous cry of the soul, beautiful but profoundly, epically sorrowful--beauty that lies too deep for tears.’As Craig von Buseck writes of these songs in his history “The Origins of Spirituals” at the Christian Broadcasting Network website: “They were the soul-cry of the black slave, longing for freedom. They were born in the fields, among the hoed rows of cotton and tobacco. They sprang to life among the salty wharves of the Atlantic harbor and the Mississippi bayou. These songs rose to heaven above the whine of the sawmill and the roar of the waterfalls that drove them. From the painful cries of the slave wench, enduring yet another violation by the master, these ballads arose. They issued forth from the sweat and heartache of a lifetime of unrewarded toil. …

“The spirituals attested to this and proclaimed the goodness of this God and His ultimate triumph over evil. They would taste freedom, they believed, across the Jordan River of death--and some sweet day in the here and now. Looking forward to that day of freedom, the slaves sang of the ‘Deep River,’ with its mighty waters flowing into distant horizons. As the embers glowed in the fire, in the heart of the forest they would sing:

Deep river--my home is over Jordan,

Deep river, Lord, I want to cross over into campground.

Don't you want to go to that Gospel feast,

That promised land where all is peace.

Deep river, Lord, I want to cross over into campground.O’Connor’s instrumental interpretation of “Deep River,” reverent but revelatory of the depth of yearning the song’s lyrics reveal, is an unambiguous cry of the soul, beautiful but profoundly, epically sorrowful--beauty that lies too deep for tears. The album ends on a similarly potent note, with a triumvirate of iconic songs--“We Shall Overcome,” the Shaker dance song “Simple Gifts” and a live version (from A Prairie Home Companion) of “America the Beautiful”--imbued with the force of personal statement, especially coming at the end of a journey that began with the hope and jubilance of “Rubber Dolly Rag.” In these songs from the distant past, O’Connor delivers a message for our divisive times as a nation.

Mark O’Connor, Caprice No. 1On his 1988 album Elysian Forest O’Connor introduced his Fidula Caprice in A, the first of six original caprices that marked the onset of his amazing transformation into a classical composer and violinist of the first rank. Since that unassuming beginning he has gone to play on the world’s greatest stages and with the world’s most famous orchestras and conductors; his orchestral compositions have received more than 600 performances with symphony orchestras; and achieved a momentary high point in 2009 with the release (and performance) of his long-awaited “Americana Symphony,” with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra as conducted by the esteemed Marin Alsop. It’s a “momentary” high point because O’Connor is only getting started, as he sees it, and more challenges loom. His self-rebranding as a classical musician and composer is one of the truly remarkable music stories of our time; that he has achieved this standing speaks to more than his gifts as an artist. It says much about his discipline, drive and vision. Which is why each triumph these days is transitory--he has come far, but has only begun his journey.

In the following interview, conducted by phone in early April, O’Connor ties the Method and American Classics together as only he can. In the end, the best way to understand what he’s driving at with this album and in pursuit of his aim to help develop a new American classical music form, reflect on his own words, as expressed to this reporter in TheBluegrassSpecial.com’s April 2009 issue, upon the release of “Americana Symphony”:

“All my creativity is born out in the present day, in my day to day life. And then as I explore and dive into it, I find connectors. I find connectors to the future and looking back into history. More often than not all of my music reflects a sort of tugboat of ideas and history and traditions that I pull along with me. One of the interesting things about American music is that it has this broader dimension. It kind of speaks about our time right now, looks towards the future by engaging people and reflects and remembers home. It remembers where we came from. Those are the aspects, I think, that really give voice to what Americana is all about, for musicians and composers to really tap into that kind of spirit and optimism. I think the sense of the beginning and the future really comes into play with creating this kind of music.”

***

‘I can still stretch; I can still include; I can still dream and wonder and all the things that you associate with the American music scene.’When we talked in December 2008, for the January 2009 cover story, the O’Connor Violin Method had not yet been published. It’s now three-plus years later and there are three volumes of the Method. Has it met your expectations it terms of its reception in academia?

It’s like any project I do; I hope it’s as big and broad and (laughs) as accepted as possible. So it’s always just like everything else I’ve done, whether it’s the New Nashville Cats or Appalachia Waltz, I think it could be bigger, it could get up there faster. Then the objective side of me sits back and says, We’ve really come a long way.

Here’s what’s going to be super-interesting about what is developing right now, and this is something I had planned from the outset, of course. My method is a solo method, which American Classics exhibit; it’s also an orchestra method. Matter of fact I’m working on Orchestra Book 2. Orchestra Book 1 is targeted for grade school beginners. Now there are not a lot of grade school programs out there for strings, unfortunately, but I want to promote that. So that was first up. Orchestra Book 2 will cater to and be appropriate for middle school orchestra level. That’s coming out this summer. I’m always looking for bridges, because I think that is the American method, that is how we operate—we’re looking for lines of communication, ways to bring our people together at the same table. So that is part of our musical method in general. In this specific case I’m using the orchestra method with the exact same materials, same pieces of music, and the solo method as a bridge—and that has never been done before for orchestra. This was part of the plan from the outset, so my full vision of the Method is still unfolding. As I release the books, the gist of the entire thing will become more and more obvious to teachers, to academic centers and to students. It’s very exciting—the great rollout, you know? But I chose to do the rollout rather than hunker down for seven years, write the whole thing at once and then release it at once. I did that for a few specific reasons, even though it’s sometimes frustrating to people who want it all and to me in dealing with people that want it all--I want to get it out there too. Even with those drawbacks here and there, the rollout is going to be absolutely key in the American Method, because one of the great attributes that I bring to it as an author is that I’m actually a working musician and teacher, and I’m out there. So it’s not like I’m sitting behind a desk and just authoring this. I’m actually playing with kids, playing with students, talking to teachers, discussing my materials, getting feedback constantly. This whole energy, the whole environment, fuels me, gives me spirit and gives me hope. And it’s going to be reflected in the quality of my materials. I had this whole thing sketched out, but every last little detail is not nailed down. I can still stretch; I can still include; I can still dream and wonder and all the things that you associate with the American music scene. So all that’s going into it.

Mark O’Connor: the Method, American music, and students putting it all togetherIn your liner notes you say American Classics “represents the American Music ‘system’ and its 400-year history,” with “system” in quotes. Why is “system” in quotes? And exactly what it does mean that these songs represent the American Music system?

As I’ve kind of unfolded the Method over the last few years, I’ve gotten my talking points more and more focused about what I’m trying to ultimately say and how I’m trying to categorize concepts and ideas. And I’ve come up with this notion that I would like to basically sell (laughs) to teachers, to academia, that there’s two great musical systems in the world, and one would be the European classical composers, and then the other great system would be what happened here. Which was largely based on individualism and a diverse community contributing to our music.

The reason I really wanted to distinguish the two systems is that for a long time American classical has been caught up in the idea that we’re like an ugly step-cousin to the European tradition and we’re struggling to keep up with them. I wanted to distinguish that what happened here was completely different from the great European system, and in my estimation, because of what’s likely to take place in the 21st Century probably more powerful now. So I’m sort of talking in terms like that, kind of pushing that American system of music, music education, how music developed here, and how it coexists alongside the European system, not having to deal with us something less than that.

As you note, a huge body of work comprises this American system. Why did these 21 tunes make the final cut as best representing what you wanted to accomplish with this album?

First and foremost, the album represents Method Book 3, so in fact they are completely tied, the exact arrangements and everything, to my Method Book 3. The choice for the music for Method Book 3, the criteria that I used, first and foremost, is what piece of music allows a student at this point in the sequence to learn how to play better. Whether it’s offering a new technique, a new style, new tempo, new key. Second, I wanted the music to be representative of the American system, in some cases American traditions or history, in many cases a true classic; I’m using the power of some of our most enduring music to engage people to learn how to play and learn to love violin and strings. So what I’m doing is interfacing what’s out there that gives the violin specifically for this book or this record the greatest opportunity to fully engage everyone involved—students, families, teachers—and of having American music usher in excellence, interest and love for music making, for learning and using the power of this specific music to make that happen. So that’s how these pieces were chosen.

Also, I wanted to have a nice selection, so I didn’t want to have too many rag tunes, too many blues tunes—I wanted to have a nice variety, so I had to whittle away. I looked especially for music that had achieved success in different communities, because every time I find an example of that I feel like there’s a special quality to that music that suggests it’s maybe more powerful than others. One of my mottos is that American folk music that had come over from Europe—the derivatives, the original germs of some of these melodies—is really good music. The folk music that stayed in Europe is not as good, because in my estimation, especially with the American scene, the best folk music travels. So whatever folk music from Europe that got here traveled here, so we already know what it is. We don’t have to attempt to try to discover some hidden folk music gem buried somewhere in Germany, because chances are that music just did not resonate with that community, with that country, and ultimately with the immigrants that moved from Germany to around the world. They didn’t take it with them. But if it traveled, if people took it with them, was a factor I used for the American music system as well.

Mark O’Connor and Rieko Aizawa perform Scott Joplin’s ragtime classic ‘The Entertainer.’ From the album American Classics.You mention Dvorak in your liner notes and it strikes me that you have in a way followed a very Dvorak-like path, in that you are as passionate about your homeland as he was his, you’ve incorporated American traditional music into your repertoire, both original and otherwise, much as he embraced Czech traditional music and wove it into some of his compositions. When he came to America and became enthralled by our folk music, he considered the melodies of Native and African Americans would comprise the foundation of an American musical style. Here too it seems to me that you’re following the Dvorak model, but with respect to an America in your case that is vastly different in makeup than what Dvorak encountered—which would explain to me why you would include “Hava Nagila,” why you would include the Mexican composers and the Canadian tune, alongside Scott Joplin and beloved bluegrass numbers such as “Boil ‘em Cabbage Down.”

That’s right. I would qualify “Boil ‘em Cabbage Down” as pre-bluegrass for accuracy’s sake. Of course when bluegrass came along in the 1930s they of course adopted a lot of the standard repertoire through the fiddlers. Also, you have to remember Dvorak only traveled to Iowa. And that’s where he saw some of the indigenous Native and African-American music. If he had been able to travel more—get down to New Orleans, right? Or down to Texas—then he would have discovered some of the other strains. No doubt. He would have picked up on that stuff so quickly, he would have immersed himself, and would probably have hung out down there for awhile and started writing. They could have given him a position down there. I kind of regret that they tried to make him so entrenched in New York and Boston, and he felt that was the do-or-die for him and that there was no other place in the States where he could have ruled the roost. I think his methods would have clearly resonated much more in places like New Orleans or Dallas, Texas, at that time, more so than in New York. So I feel like Dvorak sort of left us this wonderful memo, but many of us didn’t follow it at all; we just ignored it. I consider Dvorak an American for the amount of time he lived here, because he was for all practical purposes an immigrant just like a lot of other people. Of course who’s to know in his heart if he intended to stay? But that’s a long trip to take, to bring your family over here from Europe, especially for that time period. Most people would have stayed. I think he felt so much disdain from the most entrenched classical societies in the north that he was uncomfortable and wanted to go back. Which is really a very odd trajectory for most immigrants. He was one of the few people who turned back. And he was one of the musicians who liked American music the most.

You’ve explained very clearly about the academic aspects of this album, but whenever I listen to your music I go back to where you started from and consider it in the context of everything you’ve done, try to read it that way. For me personally, I can’t hear American Classics as a strictly academic exercise because when I hear your version of “We Shall Overcome” I think about the passion and the soul that you’ve put into your music over the years. And I think “America the Beautiful” is on this album because it’s more than a song. And the stateliness of your performance suggests your own deep feelings for its larger import in our society. It has an extra-musical message about struggle, hope and possibility that resonates strongly with Americans of a certain generation, and it reaches out to speak to us today when there is so much divisiveness in the air.

There’s something genius about how American music evolved. Sometimes we think, Oh, gosh, Mozart and Beethoven are musical geniuses, they have masterworks and we will play them to honor them. But I think there’s a lot that’s equal to that kind of power that naturally, organically, holistically happened through our diverse population, through our struggles to be more free, to try to live side by side in this grand experiment in this part of the hemisphere, and it simply could not have taken place anywhere else. So the music that was cultivated here I think does have this incredible power. When I play the violin and I can play a melody like that, to be able to try to tap into some of that depth—“Deep River” is the same kind of thing on the album and in the Method—there’s something very, very emotional but also very genius about its construction. We don’t even know who wrote some of this stuff. It’s almost like people were contributing to this beautiful masterpiece one note here, one note there until it was assembled perfectly. That’s just an incredible history, and it allows students today to feel an ownership of their own materials, that they themselves could contribute to something so beautiful and powerful as well.

Mark O’Connor and Rieko Aizawa perform Stephen Foster’s ‘Old Folks at Home,’ from American Classics.Exactly, and speaking of beautiful and power, “We Shall Overcome” begins an incredible closing triumvirate of songs on this album. It next goes to “Simple Gifts” and then the bonus track of the live version of “America the Beautiful,” a very reflective and touching version. I don’t know if this is just an accident of sequencing or if these songs were deliberately sequenced to make a point at the end of American Classics. It’s so interesting to me that you wind up here after beginning on such a jubilant, carefree note with “Rubber Dolly Rag.”

When I was nearing the end of sequencing Book 3, I made a deliberate effort to make an emotional impact as the book closes; more so than a stylistic or technical impact, even though the book and the pieces in the book in toto give you all of the above. Book 3 was such a journey of our greatest music and far reaching music that I wanted to make sure that I ended on this kind of overwhelming gift of melody that could arguably be put forward that this music, these melodies, are the greatest melodies ever written. And the fact that they comfortably live on the violin, and sound beautiful on the violin, is something I wanted to make sure the violin community knew. Part of my job with this series is to make sure that my own players knew that this music was all along inspired and in many cases written for the violin but we just forgot; we never took it to the schools, never fully developed performance music when it was time to do so. The time to do so was during Gershwin’s era, between Joplin and Gershwin. That was the time to put the American violin front and center in our culture because it was there, it was just waiting; and our academic centers pushed it out. When our academic centers became more and more powerful, and music schools started to flourish, they decided to go Vivaldi and Mozart and not go “Simple Gifts” and “We Shall Overcome” and spirituals, hoedowns, ragtime tunes and so forth. This is the great cultural correction that I want to be part of; I want to spread the good news that this music lives comfortably not only on the violin, but that much of it was inspired by this instrument. I remind people that when the violin came to America it became American immediately because of the already diverse population that was attracted to it. And as soon as that happened the violin was played differently. I think I said somewhere recently that we have to learn in this hemisphere like we’re not borrowing it from Europe. And that’s what happened—when you hear me play “We Shall Overcome” you feel a sense of connectedness to that music, to this part of the world, which the violin completely captures.

An O’Connor original from American Classics: ‘Rain Clouds,’ Mark O’Connor on violin, Rieko Aizawa, piano.Right. It’s very powerful. And yet, despite the exuberant moments, it’s a very quiet album. It’s just you and the pianist. Obviously you could have, as you’ve done in the past, enlisted the finest musicians on the planet to record with, but this is a stripped down effort that really draws you in. In that way the listener feels strongly the beauty of the melodies and the graceful rhythms and interesting textures of these songs. Was that part of the academic necessity for this album?

Yes. I wanted to make sure that the performance aspect of Book 3, American Classics, was completely there for any teaching studio at most any school, through a single piano accompanist. So I designed and arranged the piano parts to be beautiful and complementary but simple enough for average teachers and piano accompanists out there to be able to handle. So that’s the concept of accessibility. Yeah, I could have easily arranged the music for more instruments and even more prominent playing and so forth, but that would have made it less accessible to the student at the little violin studio down the street to play that piece on their recital. The main thing was to make sure this music could easily live in this environment and be successful in its performance applications, because recitals and concerts are very important. I wanted to use the piano as an interesting bridge to the more typical classical violin applications. In doing what I’m doing, basically promoting the American system, at the same time I’m still trying to draw connections and create bridges and take advantages of bridges that are already normally there. And one of the great bridges for me in this project is piano accompaniment. It’s not as well known in bluegrass circles or in certain fiddling circles, but it has a very prominent place in Texas fiddling and also in Canadian fiddling. Then of course there’s the incredible bridge to ragtime. So I look at the whole scene and say, How can I draw this in, pull it in to where it’s not so scattered around that it’s going to confuse people? So I thought the piano accompanist component to my Method series was a key musical bridge. Piano playing is something a lot of violin teachers will know a little bit about; they probably took piano in school. And then the piano also provides a wonderful musical bridge to Americana. And it is a bonafide accompaniment instrument for Canadian fiddling especially and even Texas fiddling and other regional styles of American string playing. Of course when you get into spirituals there’s a great tradition of accompaniment, as well as on the ragtime tunes. There’s a great bridge there and I wanted to expose it.

In introducing the O’Connor Orchestra Method Book 1 and Violin Method Book III, Mark O’Connor performed with Revolution, a performance group comprised of members of the Combined High School Orchestras from Abilene, TX, with conductor and teacher Darcy Radcliffe. The song performed here, ‘Olympic Reel,’ was an O’Connor commission for the 1996 Olympic Games Closing Ceremonies.Where did you find your accompanist, Rieko Aizawa? The subtlety of her playing is just about perfectly attuned to the emotional content of your playing but always serves the song to.

When I moved to New York about seven years ago now, I started seeing and meeting musicians around town, and Rieko was one of the first ones I saw and met. She played so beautifully. What’s amazing about Rieko’s playing that I’ve hardly ever run across is that she can make the most simple chord or accompaniment phrase sound like Beethoven—really just beautiful and engaging. If you listen to her piano only parts—in the Method book two CDs come with it. One is essentially the American Classics, which is me playing; then the second CD is piano accompaniment alone, so the student can play without listening to me play—you get to play with her. Sometimes when I listen to the piano accompaniment, I’m thinking, This sounds like a masterpiece. This is amazing! So I think that level and gift for playing and bringing that soul, that extra touch that she has to American music accompaniment was something that really registered with me and that I really sought out. I’m really glad Rieko’s doing the whole series.

As a side note, what’s interesting is that she’s Japanese; she was born in Japan. Of course the great rival method out there is Suzuki.

I would say these American classics resonated with her, regardless of her country of origin.

This is what I’m saying about American music. Take the blues from the Mississippi Delta. It obviously registered there, traveled up to Memphis, and then it became universal. So today, people in Japan love blues—they really love blues. We can’t get paid here, so we go over to Japan. But at the same time traditional Japanese music, like kabuki, didn’t register around the world the same way. It’s beautiful, it’s tied to a beautiful culture, but there’s something about American music that leaps off the page and travels.

Mark O’Connor’s American Classics is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024