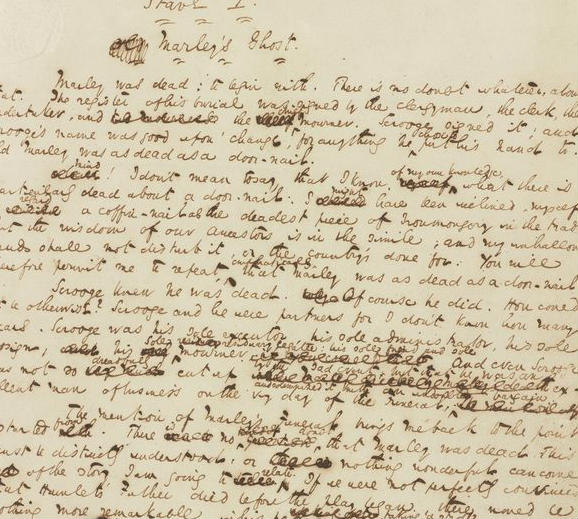

Image of Charles Dickens’s manuscript of ‘A Christmas Carol’A Dickens Bicentennial Moment

Too Busy to Read Charles Dickens? Then Try the Music

February 7 marked the two hundredth anniversary of the birth of Charles Dickens, the most celebrated English novelist of the 19th century. His novels--including classics like Oliver Twist, David Copperfield and Great Expectations--have inspired countless readers and writers, not to mention film and TV adaptations that continue to proliferate.

But unlike Shakespeare or Goethe, Dickens's influence on classical music is less pronounced--at least on first glance.

Further scrutiny shows some often surprising intersections between the music of Dickens's time and his writing, with its sweeping plots, colorful characters and mellifluous prose. Dickens himself made extensive use of music to illustrate character and create situations. "From an historical point of view these references are of utmost importance," writes James T. Lightwood in his book Charles Dickens and Music, "for they reflect to a nicety the general condition of ordinary musical life in England during the middle of the last century."

Specifically, Dickens wasn't so interested in peppering his writing with references to the classical pieces of his day but rather depicting music as it was found in an ordinary English home--the songs of the period and the average musical attainments of the lower and middle classes. Consider "The College Hornpipe," a popular dance tune of that era that Dickens drops into two of his novels: Dombey and Son and David Copperfield ("To make his example the more impressive, Mr. Micawber drank a glass of punch with an air of great enjoyment and satisfaction, and whistled the College Hornpipe," reads the passage in the latter novel).

'The College Hornpipe,' featuring Mark O'Connor (fiddle), Yo-Yo Ma (cello), Edgar Meyer (double bass), from the album Appalachian Waltz. This popular dance tune of Dickens's time is referenced in his novels David Copperfield and Dombey and SonEven a Handel allusion has working-class overtones. In Great Expectations, Pip, the main character, is fondly given the nickname of Handel by the character Herbert Pocket, in honor of Pip's upbringing as a blacksmith, and in honor of this music. "We are so harmonious--and you have been a blacksmith," Pocket says.

Dickens sometimes portrayed musicians in a humorous light and used instruments to add color and detail to a scene. Dick Swiveller consoles himself in The Old Curiosity Shop by playing the flute while David Copperfield features an ineffectual flute-playing schoolteacher.

Dickens's favorite composers were said to be Mendelssohn, Chopin and Mozart and he reportedly attended opera performances whenever traveling through continental Europe. He got to know the composer Meyerbeer and, especially, Sir Arthur Sullivan. The latter composer recalled in his memoirs roaming around Paris with Dickens, and at one point attending a performance of Gluck's Orfeo. "I went about a good deal with Dickens," Sullivan wrote. "He rushed about tremendously all the time and I was often with him... His electric vitality was extreme, but it was inspiring and not overpowering."

Lightwood noted that Dickens's love of music was not unconditional: while the author often described the music he heard on the squares and streets of London in his writing, and he couldn't bear street noise while writing, and he complained vehemently about church bells and street musicians. Even while traveling in Scotland, his troubles did not cease, as he encountered "a most infernal piper practicing under the window." Still, Dickens apparently loved to sing, and wrote a few songs and ballads like "The Ivy Green," which appears in The Pickwick Papers.

As a young man Dickens was involved with the production of one operetta, The Village Coquettes, for which he wrote the words, and John Hullah composed the music. It was produced at St. James Theater in 1836 (the score and parts were later destroyed in a fire). The world of theater clearly appealed to Dickens and as an actor and stage director he took a keen interest in all that pertained to the stage. When he was directing a play, he was always particular about the musical arrangements. A playbill of 1833 shows that he directed a private performance of Clari, an opera by Bishop.

Victorian music publishers sought to exploit the sales potential of Dickens's name and released pieces by like “The David Copperfield Polkas” and the “Christmas Carol Quadrilles.” The former can be heard in a 1997 recording:

Of course, Dickens's "A Christmas Carol" has been adapted not only as a play and a film but also in compositions by Norman Dello Joio (for solo voice and for mixed or women's chorus and piano); Benjamin Britten (the 1947 chamber orchestra composition Men of Goodwill: Variations on 'A Christmas Carol) and Thea Musgrave (the 1978 opera). In December 1946, the BBC presented the story as a ballet, with music by Vaughan Williams (On Christmas Night).

One composer who seemed to have a particular affinity with Dickens's writing was Sir Arnold Bax, whose score for the 1948 film version of Oliver Twist captured the colorful life of the eponymous orphan. The score was released in 2003 on a stereo recording for the first time, played by the BBC Philharmonic.

courtesy the WQXR blog posted at www.wqxr.org, the website of New York City's classical station WQXR.

***

Charles Dickens (February 7, 1812-June 9, 1870) Photo: British LibraryDickens’ Insights: A Epigrammatic Sampling

“Electric communication will never be a substitute for the face of someone who with their soul encourages another person to be brave and true.”

“Have a heart that never hardens, and a temper that never tires, and a touch that never hurts.”

“There are dark shadows on the earth, but its lights are stronger in the contrast.”

Next month we continue our bicentennial commemoration of Charles Dickens’s birth with the first installment of James T. Lightwood’s Charles Dickens and Music, with additional installments to follow in the ensuing months.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024