Pete Seeger (left) and Woody Guthrie at the Highlander Folk School, late 1930s or early 1940s. Photo: Highlander Folk School: A Photographic HistoryA Woody Guthrie Centennial Moment

‘Woody Guthrie, I Want You To Meet Pete Seeger’

‘From the union of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie came a new music, a citybilly blend of politics, country music and ballads.’

By David King Dunaway

On the third of March, 1940, Pete Seeger waited backstage for his first concert performance. The occasion was a “Grapes of Wrath” benefit for California migrant workers at the old Forrest Theatre, the same cause which had propelled Pete’s father into the IWW. Seeger fidgeted in the wings for hours, for the show was crowded with America’s most distinguished folk-song performers: Burl Ives, Josh White, Richard Dyer-Bennett, Aunt Molly Jackson, and Lead Belly. People milled around him, tuning guitars and peering out at the audience. The lights hummed faintly, and the heat mixed with the backstage aromas of sawdust and spilled whiskey. Performers entered and exited past Pete till the audience yawned from the lateness of the hour.

Finally he heard his name, and he walked out in front of the crowd, blinking in the lights. He couldn’t see anyone beyond the first row. He retuned his banjo (though it was already in tune), bolstered his courage, and tried to play. He couldn’t. His fingers twisted out of his control and hit the wrong strings. Then he forgot a verse.

“I was a bust,” Seeger admitted thirty-five years later. “…You see, I didn’t know how to play the five-string banjo. I tried to do it too fast, and my fingers froze up on me. And I forgot words. It was the ‘Ballad of John Hardy’: I got a polite applause for trying and retired in confusion.”

He had made a poor beginning of what turned out to be one of the important nights of his life. Fortunately, Pete was not too disappointed to appreciate the evening’s surprise star: “Woody Guthrie just ambled out, offhand and casual … a short fellow compete with a western hat, boots, blue jeans, and needing a shave, spinning out stories and singing songs he’d made up.” He sang in a dust-dry voice made of tires on hot asphalt, the midnight howl of a coyote, the rhythm of a train clacking across the plains. The effect was stunning. “Well, I just naturally wanted to know more about him. He was a big piece of my education.”

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born on Bastille Day, July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Oklahoma, later moving to Pampa, Texas, before making the dust-bowl migration to California. Despite a hard childhood, with his mother in an asylum, his sister burned in an explosion, and his father nearly bankrupt, Woody had an optimistic, come-what-may spirit. Yet a hard loner quality filled his voice: he could never really belly laugh.

Like Pete, he had little home life, and he earned attention through music. He started singing as a boy quitting school early to pick grapes and haul wood. What licks he didn’t learn from his father Charles or his fiddling uncle Jeff, he picked up off Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers records. As with the Russian writer Maxim Gorky, barbershops and saloons were his university.

Four years before meeting Pete, Woody had landed in Los Angeles, where he made a reputation with his dust bowl ballads and radio programs. There he also met Communist intellectuals, who saw in Guthrie a native proletarian: he toured with migrant workers’ camps where the treatment of the Okies and Arkies—his own people—infuriated him. As Woody’s fame grew, radical actor Will Geer mailed Pete a book of Woody’s songs. Though Pete was curious to meet Woody, the night they sang in New York he didn’t push his way through the crowd around Guthrie. Only later, at one of those cocktail parties where wealthy patrons meet performers, did Alan Lomax finally pull Pete aside ands say, “Here. Woody Guthrie, I want you to meet Pete Seeger.”

From the 1946 documentary To Hear Your Banjo Play, story and dialogue written by Alam Lomax, concerning the origins of the banjo, the development of southern folk music and its influence on Americans. Pete Seeger plays his banjo and narrates the story. Features rare performance footage of Woody Guthrie. To see the full movie visit The Film Archive.That night Pete left the theater feeling he’d failed again. The disappointment smarted. The next morning as he scanned the papers, perhaps expecting to see himself denounced by the New York Times music critic, he found news of everything except what he was looking for. Seabiscuit looked like a sure bet for the $100,000 Santa Ana purse. In Atlanta the Ku Klux Klan was campaigning to outlaw the Communist Party “and other un-American activities.” A snowstorm swept across Finland, slowing the Russian infantry’s advance toward the Nazi border. At last Pete found the review: John Steinbeck Committee To Aid Dust-Bowl Refugees. The Times ran a list of entertainers—his name was not there—and one comment: “The house was almost full.” So much for his concert debut. New Yorkers preferred Frank Sinatra in Tommy Dorsey’s new band.

If Pete was disappointed, at least Alan Lomax thought it a momentous occasion: “Go back to that night when Pete first met Woody Guthrie. You can date the renaissance of American folk song from that night. Pete knew it was his kind of music, and he began working to make it everybody’s kind of music. It was a pure, genuine fervor, the kind that saves souls.”

Alan convinced Woody and the young soul-saver to join him in a cherished project: for years, Alan told them, folklorists had omitted songs they considered political or obscene from published collections. With Alan, Pete and Woody compiled a book of political songs, beginning in New York in April. Hard Hitting Songs for Hard Hit People, as the manuscript was called, had them working feverishly. For two months, Woody sat at the typewriter, day and night, writing notes to the songs, while Pete transcribed melodies. Then Alan contacted publishers, who found the book politically “hot.” (Twenty-six years passed before the manuscript was published.)

Their part done, Woody suggested that Pete head out west with him and discover America. Seeger agreed, overcome by wanderlust. “When I first met Woody, I’d hardly been west of the Hudson River. Like most Yankees, I really didn’t see why it was so very important to go west. But Woody said, ‘It’s a big country out there, Pete, you ought to see it, and if you haven’t got money for a ticket, use the rule of thumb.” Woody came driving through in a car and said he was going to visit his family in Oklahoma and Texas. The car was not paid for by a long shot. Woody called the trip “hitch-hiking on credit.”

At the time, Pete shared a place in Arlington, Virginia, with Alan and Nicholas Ray (later known as the director of Rebel Without a Cause). He didn’t have anything to hold him; he was ready for an adventure. Pete said goodbye to Ruth and his father—who jealously called Woody’s accent and cowboy manners “affected”—and the pair took off for Oklahoma by way of Tennessee.

Another segment from To Hear Your Banjo Play (1946), featuring Woody Guthrie performance footage.They made an unlikely pair. Pete had just turned twenty-one and stood a head taller than Woody: he had innocent eyes and an unquenchable enthusiasm. “That guy Seeger,” Woody once told a friend, “I can’t make him out. He doesn’t look at girls, he doesn’t drink, he doesn’t smoke, the fellow’s weird.” Woody, on the other hand, acted hard-bitten. He ate with his cowboy hat on. Sometimes he didn’t bother taking off his pointed boots in bed, massacring the sheets. His reputation as the “dust bowl balladeer” preceded him, and record companies and radio stations chased him almost as hard as his creditors.

Woody’s element was fire, and Pete’s air. Guthrie burned across the roads of America; his singing could ignite a barroom in minutes. Volatile in his moods, Woody walked around perpetually in heat. His humor was the dray, crackly kind, and few people were warmer with children. Pete was Woody’s opposite, down to his tall, airy frame. His head pointed skyward as he frailed his banjo; his passions rarely settled down to earth. For the next few years, the pair would need each other as a flame needs oxygen.

They started down through Virginia and then across Tennessee, picking up every hitchhiker they saw until the car couldn’t hold any more, six, seven people at a time. One hitchhiker, a one-legged man on crutches called “Brooklyn Speedy,” persuaded Pete to buy him paregoric; Pete didn’t realize people drank the drug for the opium in it.

Pete nervously walked into a drugstore: “Like he told me, I said, ‘I need it for the baby.’ The druggist looked at me sharply and said, ‘This will put any baby to sleep for two years. Why do you need this much?’ Nevertheless, he sold it to me and I signed a fake name and took the paregoric back to Brooklyn Speedy. He drank it in one long gulp, the whole two ounces, and then as we drove on he closed his eyes and leaned back contentedly.”

“What does that stuff do for you?” Pete asked, half curious, half censoring. The young puritan couldn’t understand why anyone would take drugs to feel good.

“It just relaxes me and helps me forget all my troubles,” Speedy answered. “I’m sitting here in this car and the road is moving past me and that’s all I know.”

In 2006, speaking with Tim Robbins for Pacifica Radio, Pete Seeger talks about traveling and playing with Woody and how ‘This Land Is Your Land’ found its way into popular culture.After dropping off their riders and stopping to discuss music at the Highlander Folk School outside Chattanooga, they drove on. Pete breathed in the America he had dreamed of: hitchhiking, bumming meals, doing everything Americans are supposed to do while searching for the national soul. A decade before the Beats and twenty years ahead of the hippies, Pete and Woody breezed across the hot asphalt, spring turning to summer as they traveled south. Like the characters in On The Road, there was no state that bored them, no town that did not call out a rhyme or song. They savored motion itself, hungry for new faces and streets and songs.

No sooner would they stop the car and pull themselves out, stretching and wiggling their toes after the long drive, than someone would ask if they could play those instruments. “Sure,” they’d say, and despite promises to make good time, they were son sitting on a porch swapping licks. They needed no American Express or Visa cards; their songs were always good for a round of drinks and a bowl of chili.

They made a game of how far they could stretch their musical credit, with Pete getting haircuts for a song. Once when they were hungry in a river town in Mississippi they wandered into a café, two strangers asking for coffee (Woody) and two glasses of buttermilk (Pete). As their eyes got used to the darkened lunchroom, they noticed they were the only whites there. They were hungry, though, and the smells of gravy dripping from a pot of chitlins, red beans, cornbread, and beef-rib stew were irresistible. The counter girl avoided them for a while, and then told them to go; if they stayed, racists would have torn down her café.

They left, and Pete learned about America the hard way, as the characters of Easy Rider did thirty years later. He was finding what he had left New York for, a taste of “real people,” an unfiltered water glass of Folk.

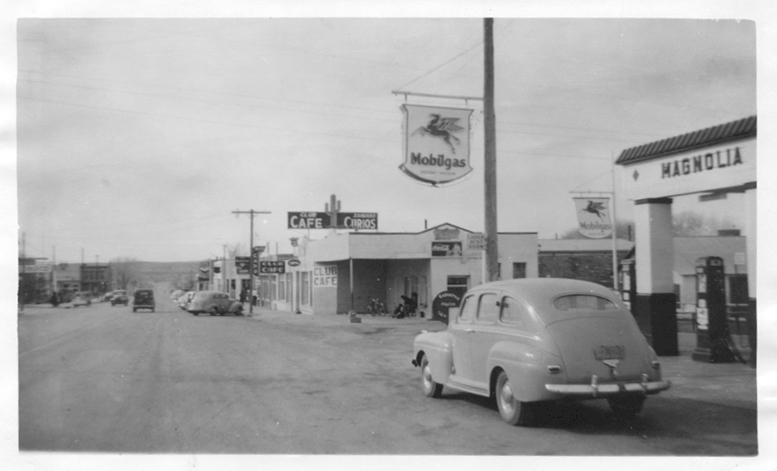

Route 66, as Woody and Pete saw it on their drive west.From Mississippi they cut west towards Woody’s home in Texas. They drove Highway 66, “the long concrete path across the country,” as John Steinbeck called it, the migrant’s road, the Okie trail, the road of Tom Joad and his family in The Grapes of Wrath. The car radio blared Gene Autry and Bob Wills, and the gospel stations woke them up Sunday mornings, after a long all-night drive. Gas money was scarce, but that made things more exciting. Pete was eager to sing in his first saloon, and he pestered Woody for a chance. “Let’s drive on,” said Woody, always a man to postpone necessity: “I think we still have a little cash.”

And drive they did, across hilly Arkansas and dust-dry Oklahoma and Texas. Hamburger stands lined the road, glorified wooden shacks with two gas pumps in front and a giant Coke sign. Inside were pieces on wire racks, steaming coffee urns, and pyramids of corn flakes in tiny boxes. They would walk in yodeling, and come out with cheeseburgers with all the trimmings.

***

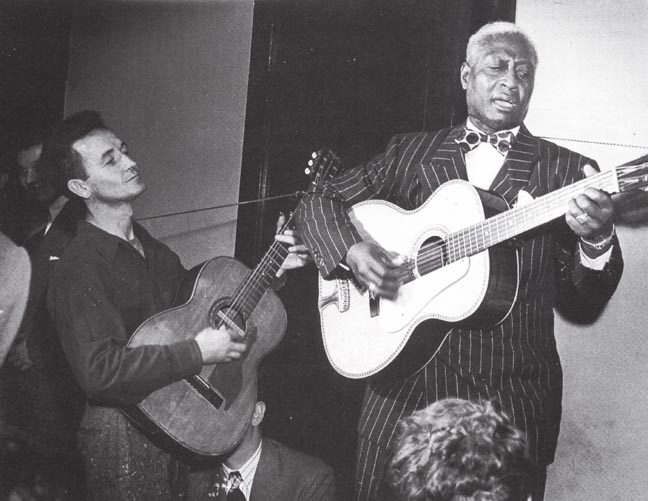

Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly: ‘From 1939 to 1941 Pete Seeger learned basic musicianship from Woody and Lead Belly. Lead Belly introduced him to the twelve-string guitar, teaching him bass runs for its doubled bass notes tuned an octave apart. Lead had patterned them after the piano breaks in Louisiana boogie-woogie. From him Pete learned the importance of rhythm. Woody taught Pete to play simple and straight: Guthrie sometimes played a ten-verse song without changing chords.’All this singing began to make a musician of Seeger. From 1939 to 1941 he learned basic musicianship from Woody and Lead Belly. Lead Belly introduced him to the twelve-string guitar, teaching him bass runs for its doubled bass notes tuned an octave apart. Lead had patterned them after the piano breaks in Louisiana boogie-woogie. From him Pete learned the importance of rhythm. Woody taught him to play simple and straight: Guthrie sometimes played a ten-verse song without changing chords. Pete and Woody differed in vocal color and tone, the qualities that distinguish two voices singing the same notes together. Woody’s voice had a flat, clear resonance; try as he might, Seeger never duplicated it, or Woody’s other mannerisms. Once during a long drive, Pete unsuccessfully tried to tell a story to introduce a song.

“Pete,” Woody said, “I can’t stand I when you just keep on talking like that! Can you cut it short sometimes?”

“Well, why don’t you ever cut it short?” Pete asked.

“Ah, well, that’s different,” Woody said.

Woody knew what he was talking about: it was different. Pete didn’t have the same timing. Woody grew up with the country music of Oklahoma and Texas; when he opened his mouth everything just poured out: all the dust and beer halls and flop houses, everything.

“Now Pete thinks he sings Woody’s way,” a former singing partner said. “He professes not to believe in dynamics or effect—yet he’s one of the most contrived, dramatic performers I’ve seen.” Seeger’s musical genius would prove interpretive rather than imitative: knowing when to flat a seventh or how to slow a tempo at the right moment to move an audience to sing. Pete eventually paid Woody back for his teaching by exposing millions to Guthrie’s music. Woody was awfully rich ore, but without the miner and the mill, many would never have seen the gold.

Music was not all Guthrie taught Seeger. Pete absorbed his healthy disinterest in commercial success, from episodes like Woody’s experience with the Model Tobacco Company, which paid him a princely two hundred dollars a week to sing on a radio show on the condition he keep his radicalism off the air and stop improvising. Woody decided he liked his freedom better than Model Tobacco, and the two parted ways. Guthrie wasn’t above commercial work, so long as it did not disturb his life style. Seeger, more of a moralist than his friend, made a creed of noncommercialism. He used this year of wandering, when politics were postponed for experience, to practice his musicianship.

***

On British TV in 1964, Pete Seeger introduces his audience to Woody GuthrieSeeger and Guthrie finally approached their destinations: two hundred miles east of Pampa, they put up at a flophouse in Oklahoma City. Though exhausted from driving, they made up a song, the first complete tune Pete remembered composing: “66 Highway Blues.” The song appeared in Hard Hitting Songs, with Woody’s fanciful introduction: “I had part of this tune in my head, but couldn’t get no front end for it. Pete fixed that up. He furnished the engine, and me the cars and then we loaded in the words and we whistled out of the yards from New York City to Oklahoma City, and when we got there we took down our banjo and git-fiddle and chugged her off just like you see it here. She’s a high roller, an easy rider, a flat wheel bouncer and a tight brake lady with a whiskey driver.”

There is a Highway coast to coast

New York to Los Angeles

I’m goin’ down that road with troubles on my mind

I got them 66 Highway BluesBeen on this road for a mighty long time,

Ten million men like me.

You drive us from yo’ town, we ramble around,

And got them 66 Highway Blues.Sometimes I think I’ll blow down a cop,

Lord, you treat me so mean.

I don’t lost my gal, I ain’t got a dime,

I got them 66 Highway Blues.I’m gonna start me a hungry man’s union,

Ain’t gonna charge no dues.

Gonna march down that road to the Wall Street Walls

A singin’ those 66 Highway Blues.The following day they met Bob and Ina Wood (who may have been the inspiration for the song “Union Maid”). The Woods were local Communist Party organizers, and they immediately recruited Pete and Woody to sing at a meeting of striking oil workers.

“There were hardly 50 or 60 people present,” Pete later wrote, “but it included some women and children who evidently couldn’t get babysitters. It also included some strange men who walked in and lined up along the back of the hall without sitting down. Bob Wood leaned over and said, ‘I’m not sure if these guys are going to try to break up this meeting or not. It’s an open meeting and we can’t kick them out. See if you can get the whole crowd singing.”

This was quite a challenge for a twenty-one-year-old on his first trip west. For centuries writers have claimed that music tames the savage instincts, but few writing this were musicians, and fewer still had to practice before a gang of union busters.

“Woody and I got the crowd singing, and you know, those guys never did break up the meeting. We found out later they had rather intended to. Perhaps it was the presence of so many women and children that deterred them—perhaps it was the singing.” This was Pete’s first time using music to avoid violence, and he received another lesson in the power of song: Music sometimes has a graver responsibility than entertaining or selling soap flakes.

***

Few people were warmer with children than Woody. ‘I’ll Write, I’ll Draw’ is from his album Songs To Grow On For Mother And ChildFinally they arrived at Woody’s home in Pampa to see his three kids and his wife, Mary, a blonde with the lean flat face of a plains woman. She’d been taking care of their family since Woody had disappeared for New York, and she was furious. “When is Woody going to get a job and settle down?” she yelled at Pete. “He can’t travel forever!” Pete and Woody looked so ragged, Mary’s parents almost turned them away from their door. After this disastrous reception, Pete—uncomfortable in the gritty poverty of Woody’s family—headed back to Oklahoma City. Woody was under pressure to stay with Mary and the kids, which he did—for a few days.

Just before departing, Pete asked, “Woody, what kind of songs will get me some coins if I sing them?”

“Well, try ‘Makes No Difference Now,’ or ‘Be Nobody’s Darling But Mine.’ And a few Jimmie Rodgers blues can’t go wrong.” This was exactly the sort of tip Pete needed.

“Now don’t start singing right away,” Woody continued. “Just keep that banjo slung on your back. You nurse a nickel beer as long as you can, sooner or later somebody’s gonna say, “Hey, kid, can you play that thing?’ Don’t be in too big a hurry. Say, ‘Well, not much.’ And keep sipping your beer. Pretty soon they’ll say, ‘Come on, I’ll give you a quarter if you’ll play me a tune.’ Now you unlimber it.”

Though Pete and Woody rarely talked about style and presentation (“We just sang; if it came our right, it came out right”), Pete had quietly absorbed Woody’s repertoire: the dust-bowl ballads and Carter Family songs, such as “Worried Man Blues.” Guthrie himself borrowed freely, without regard for tradition or copyright. “Aw, he just stole from me,” he once admitted, “but I steal from everybody. Why, I’m the biggest song stealer there ever was.”

Pete looked to Woody for authenticity, and Woody in every way fit the definition of the hillbilly or regional singers: his modes, the way he made no concession to dynamics—everything functioned on one level—railroads, love, war, death, politics, hoboes, freight trains. Woody grew upon country music and Pete on the pop tunes of the 1920s, two completely separate musical styles. When the same company owned both poop and country releases, it issued them on different labels with different artists, and sold them in different areas. From the union of Pete and Woody came a new music, a citybilly blend of politics, country music and ballads.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024