‘Everybody says music is another language, it is international--I work with Muslims and Christians, and I am Jewish. I work with Germans and I am Israeli. This is what music means to me in life.’Echoes of Forgotten Music

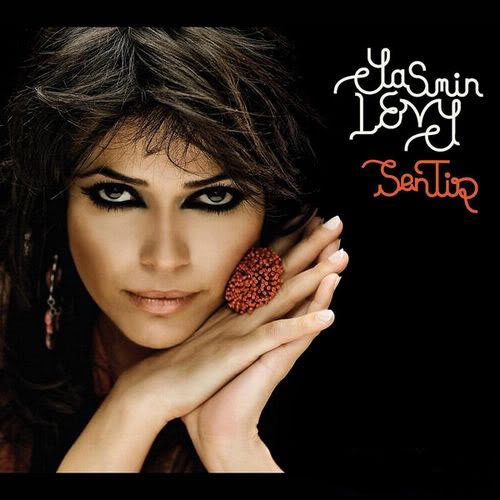

Ladino--the language of the Sephardic Jews that originated in Spain prior to their expulsion in 1492--is in danger of dying out. But one young, passionate Israeli singer steeped in the tradition of European Jewish culture is determined to reverse the decline. Her name is Yasmin Levy, and her new album, Sentir, is her strongest cross-cultural message yet in what she views as a ‘musical reconciliation of history.’

The story of how Yasmin Levy came to lead the preservation of a vital tradition begins before she was even born. The irony is that in preserving this tradition she's going against the wishes of her late father,Yitzak (Isaac) Levy, even as she becomes an international world music star as the leading exponent of Ladino music.

A composer and cantor, Isaac Levy was born in Turkey in 1919 and grew up in Jerusalem. One day while he was at home with his mother, his ears perked up as she sang an old song while cleaning house. Not only did he realize he should record this ancient tune, but that he should preserve the songs others in his community knew as well. He went from household to household, recording any family that would sing anything in Ladino, a mixture of old Castilian, Spanish and the local languages. He wrote down the lyrics and the melodies, thus preserving songs that would have died with the people he recorded. Eventually he published four books of romantic songs and ten books of liturgical songs. The Jews preserved these songs wherever they settled after their expulsion from Spain in 1492: the Balkan countries, Turkey and northern Morocco. Isaac Levy's anthology is a milestone in the documentation and revival of this 1,000-year-old folk music.

Yasmin Levy, The Making of SentirIsaac Levy was the Alan Lomax of Ladino music, every bit as important to it as Lomax was to folk music. But whereas Lomax preserved his recordings and notes, Levy stipulated that upon his death (he passed away when Yasmin, the youngest of five Levy children, was one year old) all his work should be destroyed.

"My father came from Turkey to Jerusalem when he was three years old and began the project of taping the songs as an adult," Yasmin explains. "It was his life's work and he was worried that after his death, there would be people who disagreed with the way he recorded the notes for the music he heard from elderly people who sang it to him. That's why he ordered that his entire collection of recordings be destroyed after his death. Every time he would say to Mom: `What will you do after I die?' she would always answer: `I'll tear everything up.' I remember myself the many spools that the whole family tore and I even hurt my finger on one of the coils. In my opinion, it's terrible, and if he were alive I'd ask him, 'Why, why did you do it?" But from the stories about my father, I know that he was very critical and determined and perhaps his sensitivity about his life's work is understandable."

The 35-year-old Levy does not remember her father at all; she learned about his legacy from her mother, Kochava: "My mother was a wonderful singer, an academy graduate, but she gave up singing when she met my father and devoted her whole life to him. She was his second wife and 27 years his junior and because of his objection to her working as a singer, became a housewife. Instead of singing, she served food to all the singers who used to visit us. But she learned all the songs from him and after he died, she slowly returned to music.

Yasmin Levy, ‘El Amor Contigo,’ from Sentir"Around five years ago, after I had started singing, I learned everything from her--the words, how to express the emotion. We spent whole days working on it and she corrected me based on what she had learned from Dad--and it's strange that I, the daughter who doesn't remember him, am the only one of my siblings who followed in his footsteps."

After two years of national service, Levy began accompanying her mother professionally, and not long after that did speculation begin about a solo career for Isaac Levy's daughter. A young, striking, dark-eyed beauty, she would have been a natural pop star, setting young mens' hearts aflutter with every alluring glance and smoldering performance. Yet, she took the road less traveled, and it has made all the difference, as she employs the full expressive palette of her voice to articulate the emotive power of the songs her father preserved.

Her first album, 2004's Romance and Yasmin, earned her a Best Newcomer nomination in the Awards for World Music, and was a remarkably original statement of her intent to bring her own ideas to this centuries-old music.

"When I did the first album, which is all Sepahardic songs, I brought with me all Turkish instruments--darbucka, oud, violin--and arrangements because my father is Turkish, and he grew up on this music.

"Then I got to know flamenco when I got a scholarship to Seville [Note: Seville UNESCO City of Music,Spain]. I received the scholarship for three years but life took me to another place, and I left after three months. But you have to live the lifestyle; people are learning flamenco from the age of three. You need to do it for five years at least. I took what I could and did some flamenco arrangements for my follow-up CD [La Juderia, 2005]. People argue with me whether it is flamenco music. I just want to experiment with the arrangements--I never touch the lyrics or the melody; they are not mine. I just put another outfit on the song. That's why people like it. They say it sounds flamenco, but it's Ladino."

Yasmin Levy, ‘Algo De Ti,’ from SentirWith the release of La Juderia, critics began sharpening their knives before appraising Levy's work. Though it had a flamenco feel, the album showcases mostly Ladino music. Purists from both camps objected to the stylistic crossover, but the album actually broadened Levy's appeal to younger fans. To the artist, the natural nexus of soul and technique required in Ladino and flamenco make for an appealing blend.

"I think flamenco is more difficult to play because of the rhythm--it's a way of life," she says. "It's very difficult to sing. Ladino is simple, anyone can sing it but you still have to feel it, like flamenco. It's music from the street."

Yasmin Levy performs the title track of her third album, Mano Suave, live on Dutch televisionCome 2007, however, the release of her third album, Mano Suave, met with near-across-the-board acclaim. Writing in FlyGlobalMusic.com on February 4, 2008, Conon Murphy declared the Israeli singer's new Lucy Doran-produced long player "is another small step closer to the classic album we are waiting for."

Observed Murphy: "Levy's emotional phrasing is deployed in a range of styles that circle the central Sephardic sound--Paraguayan harp, kora, flamenco guitar, Arabic instruments such as oud, ney flute and qanun all feature--with a noticeable inclination towards Turkish and North African influences (Anglo-North African singer Natacha Atlas is another guest artist)? 'Una Noche Mas' is the highlight, and has the feeling of an instant World Music classic. Set to a waltz-like rhythm, the track builds in intensity against an echoing (almost '60s sounding) production, with Yasmin at her emotional, sultry best. Elsewhere, there are one or two moments where Yasmin could be accused of playing things too safely, in particular when the roots influences are moved to the background in favour of lush strings and a smoothed out, emotionless vocal tone (not so much Moorish as MORish?), leaving the album a couple of tracks short of being the truly great album of which she is surely capable. That's a minor gripe, however, and if Yasmin Levy's first album, Romance and Yasmin, was a remarkable statement of intent, and the follow-up, La Juderia, a worthy exercise in marrying traditional Spanish modes--especially flamenco--with the music of the Sephardic Jews, then Mano Suave takes Ladino one step further into a diverse and at times thrilling mix of emotive singing and evocative roots music. This is one to enjoy while awaiting the next step with eager anticipation."

Yasmin Levy on Sentir: ‘To find an audience for these songs today, I need to make them live again.’In 2009 her Sentir album (which was released in the North American market in late 2011 and promoted with a tour of Canada and selected U.S. cities last month) was met with a degree of praise (and some barbs) that marked it as what FlyGobalMusic.com's Murphy called "the classic album we've been waiting for." With fashionable Spanish producer Javier Limón on board for Sentir, Levy has now exceeded even her own expectations of how far her music could go. "You have to remember these songs were never meant for the stage," she explains, "they were for the synagogue, and definitely not for a female singer!"

Limón does for Levy what Mark Ronson did for Amy Winehouse. "I had dreamed of working with him for eight years," says Levy. "Finally it happened and I moved to Madrid for two months to make the album with him. I sat down and said I want to lose the 'oriental' sound with this one and do flamenco. He said: 'Stop. Let's keep you the way you are.'"

Yasmin Levy, ‘Nos Llego el Final,’ from SentirThe result is a fresh, light sound, particularly considering the loaded history the songs carry with them; the music of a people trapped in ghettos and exile. "I wanted to get away from the heavy, reverential sound," says Levy. "I know these songs are old and sad--all of my songs would be sad if I could get away with it!--but to find an audience for them today, I need to make them live again."

Levy had never planned to be a Ladino singer. "I was asked by the Ladino authority, in Israel, whether I would consider making a Ladino album and I thought, why not?" she recalls. "Since that first album I have not been able to leave the Ladino songbook. And I don't think I ever will. The Sephardi songs are much bigger than me. Because it is an endangered language, the only live and kicking thing that will remain will be those songs. It has become a mission for me. I have tried singing in other languages--Hebrew, for instance--but it's not the same. I mean, I go and buy milk in Hebrew."

It is an irony that had her father lived, Levy may not have become the singer she is today. "I am sure I would not be. It was never encouraged as a profession in our house," she says. "You know how it is, the Jewish state of mind--Jewish children are to be lawyers, engineers, professionals. Also, I was so in awe of my parents' voices--my mother's is like an angel; I would not dare join them."

Father and daughter united in song: Yasmin Levy sings 'Una Pastora' as a duet with her late father on SentirHer father metaphorically joins her on stage every night ("These songs are a way to be with my father. I don't remember him but I sing with him every single night. I live his life.") and via the miracles of modern technology sings with his daughter on Sentir, too, on the song "Una Pastora." Much to Ms. Levy's surprise, mind you: "I never thought I would be able to do that. It is very scary," she says.

Levy's home town of Jerusalem, where her mother, brothers and sisters still live, provides her with unending inspiration. That she hails from the Golden City is the first thing she tells her audience when she gets on stage. "Jerusalem is my being," she says. "My mum says we are Jerusalem stone. Jerusalem is my dreams, my hopes, my music, my life-a stranger could never understand. I sing about longing for Jerusalem and I really do, whenever I am away from it."

The city also has taught her to watch her back, be expectant of attack, though she can cite only one instance where she has felt threatened at an international performance: when the word "Yahud" (Jew in Arabic) was shouted out from the crowd.

Though she describes the music scene in Israel as "flourishing," Levy is not in touch with it herself, preferring the songs of chazans or the music of old stars like the flamenco singer Antonio Molina, Edith Piaf and Billie Holiday to the funk and pop of young Israeli musicians.But she is not alone in dipping into the cantorial songbook. "All of Israel is starting to look for its roots now. People have a hunger for these songs. A lot of famous Israeli singers are recording them now."

Yasmin Levy, live in Stockholm, Sweden, performs ‘Jaco’ from Sentira, at The Great Synagogue Stockholm, October 23, 2011

At the end of each of her albums, Levy closes with a song of prayer; in Sentir, it is "Yigdal." In it, she thanks God for her voice and her music. But she answers in the negative when asked if she feels her music is powerful enough to help ease the conflict in her native land.

"I am not so innocent to think that a musician can bring about peace in a country with such deep divides. Although there was the time when an Iranian man in his twenties sent an email to his mum after he had been to my concert, saying his life would never be the same because he had seen an Israeli woman sharing love and he had only seen Israelis through hate. I do think music brings about harmony, a way to meet and to see a person differently,"

“I am proud to combine the two cultures of Ladino and flamenco, while mixing in Middle Eastern influences,” she said upon learning that her work had earned her the 2008 Anna Lindh Euro-Meditarranean Foundation Award for promoting cross-cultural dialogue between musicians from three cultures. “I am embarking on a 500-year-old musical journey, taking Ladino to Andalusia and mixing it with flamenco, the style that still bears the musical imprint of the old Moorish and Jewish-Spanish world and the sound of the Arab world. In a way it is a ‘musical reconciliation’ of history.”

Indeed, the marriage of styles she officiates on her albums is consistent with Yasmin's approach to her culture and her aims as an artist: "I tell myself that my music is a big thing, bringing people together. My band members come from all parts of the world. I have Armenian and Turkish people with me in the concert band and they are like brothers. I have members from the UK, Persia (Iran) and even Chile. Everybody says music is another language, it is international--I work with Muslims and Christians, and I am Jewish. I work with Germans and I am Israeli.

"This is what music means to me in life."

Yasmin Levy’s Sentira is available at www.amazon.com

Sources:

The Jewish Chronicle

Interview: Yasmin Levy by Nicola Christie, February 11, 2010

FlyGlobalMusic.com

Review of Mano Sauve by Conon Murphy2006 interview: "Yasmin Levy--Sing Like a Butterfly" by Conon Murphy

Haaretz.com

2003 Interview: "Echoes of Forgotten Music," by Noam Ben Zeev

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024