Larry Levine at the Gold Star console in session with Phil Spector (Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns)‘He Was In Another World’

Phil Spector’s go-to engineer, Larry Levine, reflects on the Gold Star years

By David McGee

Multiple factors contributed to the construction of Phil Spector’s famous Wall of Sound--not least being the overabundance of gifted musicians the flamboyant producer employed in Studio A of Los Angeles’ Gold Star Studios--but one of its most critical components was the clever deployment of an echo chamber by Spector’s go-to engineer Larry Levine.

Larry Levine"He made Phil Spector a genius by applying the simple logic of using echo chamber," Gold Star's co-owner (and Levine’s cousin) Stan Ross told the Los Angeles Times following Levine’s death on May 5, 2008. "Phil had a tendency of overbooking the room, and there were more musicians than there should have been in the studio. It began to saturate the walls, and you couldn't make it happen unless you get some separation, and the only way you could do that is by getting some echo and making the room sound larger. . . .

"I showed him how you work this echo chamber thing and he got into it and sure enough it worked. . . . If Phil had gone into another place to do it, it would have been a normal record without any wall of sound. . . . It gave it dimension, it sounded like it was a football field."

Born in New York but raised in Los Angeles from the age of one, Larry Levine took a class in radio at DeVry Institute while living in Chicago with his father in 1946 and ’47. After serving in the Army, he went to work in 1952 for North American Aviation testing electronic equipment.

From the 1983 documentary Da Doo Ron Ron by Binia Tymieniecka, for U.K. television, Larry Levine and Stan Ross (and others) discuss the making of the Wall of Sound. Includes the Crystals performing ‘Da Doo Ron Ro,’ and the Ronettes performing ‘Be My Baby.’While Levine was in the Army, his cousin Stan Ross, with his partner Dave Gold, opened Gold Star Studios on the corner of Santa Monica and Vine in L.A. in 1950. After moving back to L.A. Levine began hanging around the studio and helping engineer demos, airchecks and infrequent recording sessions. Eventually he was hired full time after Ross and Gold received authorization for Levine’s position to be considered on-the-job training, which qualified for a government subsidy.

“Almost everything we did at that time was demos,” Levine told this writer in a 1996 interview published in the recording industry trade publication Pro Sound News. “We only had one tape machine, we were recording mostly directly to disc, so it was that old method of counting off with your fingers in the control room and pointing them in--you know, the real glamorous stuff, by the seat of your pants. That was what we were doing, basically, demos, and air check, and special promotional things someone might bring in. I remember there was a talking turkey, which had a disc inside the turkey, a promotional thing. Those sort of things is what we were doing. It wasn't until the middle '50s, when Elvis broke out, that the music business opened up for smaller groups to get records. Gold Star was in a perfect position to do that, because they didn't charge much at all. People would do demos and get the demos released as records. There were all these scams going on too. I kinda stayed away from knowing anything about them, but I would hear all these stories. Everybody was cheating everybody. I guess that was part of the business. But these little records would end up somehow, and if they had something, off they'd go. Stan was the engineer; again, I was in training or in waiting or whatever you want to call it. But Stan was the engineer.”

A fan of the big bands he had grown up with, Levine abhorred rock ‘n’ roll, but his apprenticeship with cousin Stan changed his mind about it. “What happened was that as I got to work on some records that were being released, I would listen to the radio hoping to hear a record I had made. So in listening to all of the material you soon become a fan. It's like I remember hearing about an art appreciation course that was given at the Louvre. What it consisted of was spending a month, six to eight hours each day, and all you would do would be wander. And when you started you picked out your ten favorites, and automatically you gravitated to the great masters, just by being around them. So the same thing is basically true in music. I knew the rock and roll, the stuff I hated, and then I learned to appreciate what was good about it.”

From the A&E Biography of Phil Spector, the early years, including his first visit to Gold Star Studios to record ‘To Know Him Is To Love Him’The vaunted Gold Star echo chamber was the brainchild of Dave Gold, Levine said. “We knew we needed echo. And there was a hallway from the back door entrance to the front door. The hallway was like three feet wide, and just outside the door and down the other end of the hall was the microphone to pick up ambient sound--that was our echo. We're lucky we didn't kill ourselves. We built a small ceiling up above the hallway and blocked it off, so that we had cubicles running the length of the hallway maybe two feet high and three feet wide. And we went in there and painted with slate to harden up the walls without any breathing gear or anything. I don't know how we survived that. But it sounded terrible when we finished it. We used the bathroom there for a while. I remember putting a girl in there, a singer, in the toilet, and she's singing this song called ‘Well of Loneliness.’ I kept breaking up the whole time we were recording it. That was the end of that experiment.

“Dave, out of a book, decided to build these chambers. So he built them side by side. The way we got into them was through a crawl hole on the back wall of the studio into the cubicles. And we had a cheap ribbon microphone we weren't using and an eight-inch, or maybe a twelve-inch, speaker down at one end. And it was great. It was great. What was so great was you'd stand in there in the dark and it was really eerie, because you could hear all the reverberation, which is better than I've ever heard in any other chamber I've walked into. I mean, it was all there then. They were beautiful chambers. Phil brought it to the forefront.”

In 1957 Phil Spector entered the Gold Star facility to cut his first hit, the Tedddy Bears’ (his own group) “To Know Him Is To Love Him.” He was still a student at Fairfax High School at the time. Levine wasn’t in the studio for the Teddy Bears session but he’d run into Spector before and wasn’t impressed. “I didn't care much for Phil,” he said. “He rubbed me the wrong way. He didn't try to do that. He just seemed like a snot-nosed kid to me.”

Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans, ‘Not Too Young To Get Married,’ produced by Phil Spector, engineered by Larry Levine (1963)To the comment that Spector was indeed a “snot-nosed kid” at the time in question, Levine agreed but added: “A lot of what he appeared, or a lot of what people thought, was not true. It's just the way some people carry themselves, their ambiance. I'll tell you, I know for a fact that more strange things happened to me around Phil. We didn't socialize, but I would do things like after the sessions, we'd go out to breakfast, or whatever. And more strange things happened when I was with Phil, and he didn't do anything really to bring them on. It was just this aura he had.”

What kind of strange things?

“I remember going to his hotel one time and there was a shooting there. He had nothing to do with that, but it was all hectic, going on. I remember a couple of times when we went out to breakfast afterwards, and people would gather around him and want to hurt him. He finally got some bodyguards. But it's strange, it was just being there and Phil would draw this. Like I say, it was not something he did to bring it on. Some people have different auras.”

On Working with Spector

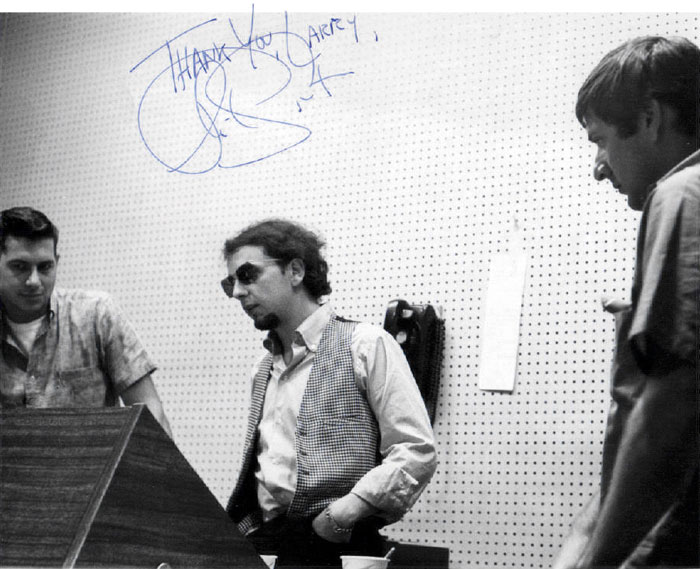

Larry Levine (left) in the Gold Star booth with Phil Spector and Sonny Bono, in a photo signed by Spector, ‘Thank you, Larry, Phil’ (Photo: Larry Levine)Gold Star had a long and illustrious history, but music historians always go back to the Spector era as the golden era of Gold Star.

Larry Levine: No doubt it was.

How much did Phil change from the "snot nosed kid" you knew in the early days to when he really hit his stride with those recordings on his Philles label?

Levine: As I worked with Phil I grew to know him. When you get down inside of Phil, I love Phil, but how many people get that chance? You have to have been with him for a time. So not certainly right away when I started working with him, I was in awe of his talent and I knew what he had done back in New York. At Gold Star he had done the Teddy Bears and he had done the Paris Sisters. Then he went back to New York and did some great stuff with the Drifters, all these groups.

Darlene Love, ‘Today I Met the Boy I’m Gonna Marry,’ produced by Phil Spector, engineered by Larry Levine (1963)He apprenticed with Leiber and Stoller in New York.

Levine: Right. When he came back to do "He's a Rebel," the Crystals wouldn't come out here. They were afraid of flying. So he got this group of backup singers, with Darlene Love, and called them the Crystals. It was a big record. But what happened is he came back three weeks later, said he'd been searching for the studio that would give him the sound he wanted, what he heard in his head, and off of "He's A Rebel" he decided Gold Star would do it. So he came back to do "Zip a Dee Do Dah." He had to work on a weekend, and Stan didn't want to work then. So he worked with me on that, and the experiences we had on that--I didn't know the song was "Zip a Dee Do Dah" until the very end. We'd been working trying to get what he wanted for maybe three, three and a half hours, and all my levels were pinning, and I knew if I tried to record that I was going to be in big trouble. But I couldn't work up the nerve to tell him that. But I knew that I wasn't going to be able to record it. So finally I got up the nerve, and I turned all the faders off. I knew what he was gonna do--he started screaming at me, "I was there! I had it real close!" And I said, "It won't work. I can't record it." So I started bringing back the microphones one at a time and balancing them at a level I could work with. And just before I got to the last microphone, Phil said, "That's the sound! Let's record it!" He said, "Don't turn it on! Leave it just like that! And let's record it." We got it in one take. I asked the name of the song and he said, "Zip a Dee Do Dah." I thought he was putting me on. Then when I realized it was "Zip a Dee Do Dah" and how this thing opened, I literally fell off my chair. It was the greatest thing I'd ever heard. So we did it one take, put the voices on in one take. We had a two-track and a mono, so I recorded the voices on two-track and played it back, and Phil told me to make a mono of it at the same time--put the two-track back to mono. But the playback, that was it--one take there. I said, "You know, the voices were a little soft when I started out. I realized you don't turn them up right away." He said, "No, I like it. That's it." That was it. That's the record. What happened is he went back to New York with it, and Gold Star at that point in time was a big family of creative people. Other producers, artists, would come into the studio, and I couldn't contain myself. I would say, "Listen, I'm going to take you in and play you a song. And if you tell me there's a chance it won't be in the top ten, I'll eat the tape." They'd look at me like I was crazy. Again, in this great listening environment that was Studio A in Gold Star, the control room, that thing, “Zip a Dee Doo Dah,” well, it was unique, certainly, but so tremendous that no one ever asked me to eat the tape. Everybody was amazed by that.

When Phil came back from New York he said, "I'm putting the record out. I have to put it out, because everybody in Hollywood's heard it!" He was happy about it; he wasn't angry. He said, "You played it for everybody in Hollywood. I've gotta put the thing out." Matter of fact, he said when he got back to New York and played the demo for a publisher, or a record company--he played it for somebody. I don't know if you remember the intro on that thing. He said when they got six bars into the intro, the guy took the needle off and said, "I'll give you ten thousand dollars up front, let me put out the record."

You came out of a radio background, but looking back did you learn things about being an engineer from working with a guy like Spector?

Levine: Oh absolutely. Oh, yeah.

The Crystals, ‘He Hit Me (And It Felt Like a Kiss),’ written by Carole King and Gerry Goffin, produced by Phil Spector, engineered by Larry Levine (1962). The song was inspired by Little Eva telling the writers that her boyfriend beat her out of love for her. The title phrase occurs in a critical scene of Rodgers and Hammerstein’s 1947 musical, Carousel, and before that was used in the final scene of Frank Borzage’s 1930 film Lilom.He had to have picked up something working with Leiber and Stoller. Was he heavily involved in directing the technical blueprint for those recordings?

Levine: Not like you might think. Phil was absolutely aware of all of the technical. He didn't do anything much, but you soon found out that you couldn't bullshit him. I don't know that I would have anyway, because I wasn't that kind of guy. We went to other studios a couple of times, worked with other engineers. And they tried. What Phil said to me was, he knew he could trust whatever was going to happen, he knew how I would react. So that was his main consideration. I learned from Phil in doing those kinds of records. I certainly learned microphone placement, although he never conducted anything. That was not his job. His job was to make a hit record. In fact he told me once--who was that great Swedish director?

Bergman?

Levine: Yeah. He said he had read a piece by Bergman that said the reason he wouldn't shoot in the United States wasn't because they didn't have great, talented people but that using the people he worked with all the time he knew what to expect from them. And all he had to do was concentrate on the thirty seconds or a minute of creativity--didn't have to worry about what they were doing. So this is the thing that Phil kind of had for me.

His approach at that time as a producer is part of his legend. And that legend says that he was a real dictator in the studio, hard on his artists, very demanding of the musicians. Neither of which is inherently bad--he was trying to make hits, after all, and this was business, not doodling around in a garage, but those who were there have said his mania was extreme. Is that consistent with what you witnessed in those years?

Levine: In a way it's true. I think the artists were treated like shit. But that was his way; he didn't set out to treat them that way. It's just that he didn't care about the artists--well, he cared about the artists. But he once said he could make a hit record taking somebody off the street. And that's true; he could have. He was in another world, I think is the best way to put it, and he wasn't concerned with the artists. So the artists suffered. He didn't communicate with them, didn't let them know what was happening, didn't commiserate with them. Phil was divorced at points. That's not to say that they didn't have good times with him either. When things were going good Phil would do standup comedy for twenty minutes, half an hour and everybody was in stitches. The musicians all loved him. He wasn't a tyrant all the time.

The Crystals, ‘He’s Sure the Boy I Love’ (1963)It sounds like his relationship with you was on a much more even keel. Or did he get irritated at you too?

Levine: No, I'm a little older than Phil. And I brought a little more savvy to the job. I told him what was wrong and he listened to me. Even though he was certainly intelligent enough to know what was wrong. Our relationship was more like a big brother. And, because of my ear--you know, when you're in the studio you've got to have someone to bounce off of, I don't care if you're the greatest producer in the world, you've got to have somebody to bounce off. And Phil had me. Otherwise, there's no way to stay objective.

Another thing that was unique about Phil was that when it came to mixing down, he would leave the control room, and I'd mix it until I was satisfied that I had what I wanted. Then I'd call Phil back in and he'd critique it. He'd tell me what was missing from it or what he felt. And then he'd leave again. I didn't have somebody looking over my shoulder, so I wasn't trying to create for them instead of for me. It worked great that way. But he's the only producer that ever worked that way.

The Righteous Brothers, ‘You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,’ produced by Phil Spector, engineered by Larry Levine (#1, 1964). ‘The apex for me was ‘Lovin’ Feelin’,’ says Levine. ‘That record was totally from left field. Nothing was being done of that ilk.’I think you can put producers in three categories: the hardest producer to work with was one who didn't know what he wanted and couldn't communicate with people. We had a lot of those. Then there was the second one, a producer who didn't know what he wanted but he was willing to listen. He was better to work with. Then there were guys like Phil and Herb Alpert, who knew what they wanted and could communicate--those were the best to work with.

I think the apex for me was "Lovin' Feelin’.” That record was totally from left field. Nothing was being done of that ilk. You couldn't dance to it--that was the criteria that a lot of people used in those days. You'd be surprised at the producers and executives, they'd be listening to the playback and dancing to see how it felt for dancing. So here's none of that, and it was emotional. It created all these beautiful pictures. I always tried to create a picture when I mixed. I didn't very often succeed. But when I did it was really good. Either visualizing what it was going to look like to people or where I saw all of this happening. It's very difficult to put into words what I saw. But there are great records that just create a picture. I remember the first time I heard "Pretty Woman," and I just pictured this drum sitting up on a pedestal eight feet high and boom-boom. It was controlling everything. That was the picture I saw in the studio.

You left Gold Star in January of '67 and joined A&M. Why did you leave?

Levine: Because they asked me to. No, well, Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss had created the label and their thing took off. I had worked with them--the first album I did with Herb was South of the Border. This thing started growing. It was kind of underground at first. But all these people loved that music. I remember giving an album to my uncle. And he said, "I don't wanna hear your stuff. I don't like rock and roll." I said, "You'll like this." He said, "I won't like it." He called me up the next day and said, "This is so great!" So when they hit big in '65, they ended up buying, in 1966, the old Charlie Chaplin lot. They said to me, "What do you think about coming over and building a studio?" I thought about it for about 30 seconds and I said, "Sure." I told Stan and Dave right away. There was no doubt that I would do it. There was more money to be made, and it was a great chance. So I went there in January of '67.

During his A&M years Larry Levine won a Grammy Award in 1966 for Best Engineered Recording--Non-Classical for “A Taste of Honey” by Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass. The recording also won a Grammy as Record of the Year. He also helped engineer the Beach Boys’ classic album Pet Sounds. Levine died on his 80th birthday, May 8, in 2008.

Follow this link to a website devoted to the work of Larry Levine.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024