Pleasures of Music

Music Is Infinite

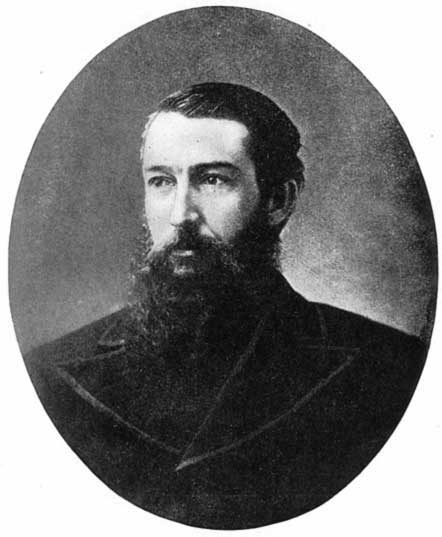

By Sidney Lanier

(Flutist, composer and poet, author of the Centennial Cantata of 1876, Sidney Lanier [February 3, 1842-September 7, 1881] was a born and trained musician who has left a volume of excellent essays on music. The following is from a manuscript fragment first printed in his collected works.)

All shades in an American audience; from those who cry give us a tune, something quick and devilish, to those who find in music a religion of the emotions and a comfort and triumph in the darkest hour of the soul. Composers must not be characterized. We must not take Beethoven and Mozart and stick a pin through each one like so many bugs and butterflies in a glass case, and say this one Beethoven belongs to the class of the big beetles. (Coleoptera gigans) and Mozart to the class of the butterflies (_____!). If we do, the composers will become as dry and dusty as an entomologist’s collection.

In the same way we must not assign too definite ideas to musical composition: this means longing, etc. this means etc., etc. (Bayard Taylor’s experience with Wagner’s music: one of the party said it meant moonlight, another sea, another so and so, etc., etc.: on the other hand, that burlesque orchestra piece where the sun was represented rising over Pike County, Arkansas, (piccolo and drum), etc. Cf. Thomas Hood’s Musical Party. Music is vague: purposely so. This is no objection. If it is, the Bible must fall. The Bible furnishes a text for every creed. The Mormon allows you to have twenty wives, and furnishes you with good authority from the Bible, while the old George Raff and his Harmonists (and the Catholic Priest) allow you no wife, and give you good authority from the Bible: the slaveholder draws his warrant from the Bible, the abolitionist draws his warrant from the Bible: the Unitarian proves from the Bible that there is but one person in the Godhead, the Trinitarian that there are three. Arnold reads the plain and lucid statements from St. Matthew and Paul and arrives at Rationalism, while from the more mystical writings of St. John a thousand mystagogues construct a thousand forms of belief. This is because the Bible is so great; and it is purely because music is so great that it yields aid and comfort to so many theories. --from NOTES AND FRAGMENTS (undated)

***

Music And The Deity

By Sir Thomas Browne

Sir Thomas Browne (October 19, 1605-October 19. 1682) was an English author of varied works that reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including medicine, religion, science and the esoteric. Browne's writings display a deep curiosity towards the natural world, influenced by the scientific revolution of Baconian enquiry, while his Christian faith exuded tolerance and goodwill towards humanity in an often intolerant era. A consummate literary craftsman, Browne's works are permeated by frequent reference to Classical and Biblical sources and to his own highly idiosyncratic personality. His literary style varies according to genre, resulting in a rich, unusual prose that ranges from rough notebook observations to the highest baroque eloquence. Although he was described as suffering from melancholia, Browne's writings are also characterized by wit and subtle humor.

His first well-known work, Religio Medici (The Religion of a Physician), was first circulated in manuscript among his friends; to Browne’s surprise, an unauthorized edition appeared in 1642. It contained a number of religious speculations that might be considered unorthodox. An authorized text with some of the controversial matter removed appeared in 1643. The expurgation did not end the controversy; in 1645, Alexander Ross attacked Religio Medici in his Medicus Medicatus (The Doctor, Doctored) and in fact the book was placed upon the Papal index of forbidden reading for Catholics in the same year. In Religio Medici, Browne confirmed his belief in the existence of witches but also illuminated what he heard as a link between music and God, as the following passage attests.

It is my temper, and I like it the better, to affect all harmony; and sure there is musick even in the beauty, and the silent note which Cupid strikes, far sweeter than the sound of an instrument. For there is a musick where ever there is a harmony, order or proportion; and thus far we may maintain the musick of the Spheares: for those well-ordered motions, and regular paces, though they give no sound unto the ear, yet to the understanding they strike a note most full of harmony. Whosever is harmonically composed, delights in harmony; which makes me much distrust the symmetry of those heads which declaim against all Church-Musick. For my self, not only from my obedience, but my particular Genius, I do embrace it: for even that vulgar and Tavern-Musick, which makes one man merry, another mad, strikes in me a deep fit of devotion, and a profound contemplation of the first Composer. There is something in it of Divinity more than the ear discovers: it is an Hieroglyphical and shadowed lesson of the whole World, and creatures of God; such a melody to the ear, as the whole World well understood, would afford the understanding. In brief, it is a sensible fit of that harmony, which intellectually sounds in the ears of God. I will not say with Plato, the soul is an harmony, but harmonical, and hath its nearest sympathy unto Musick: thus some whose temper of body agrees, and humours the constitution of their souls, are born Poets, though indeed all are naturally inclined unto Rhythme. This made Tacitus in the very first line of his Story, fall upon a verse, and Cicero, the worst of Poets, but declaiming for a Poet, falls in the very first sentence upon a perfect Hexamater. I feel not in me those sordid and unchristian desires of my profession; I do not secretly implore and wish for Plagues, rejoice at Famines, revolve Ephemerides and Almanacks, in expectation of malignant Aspects, fatal Conjunctions, and Eclipses: I rejoice not at unwholesome Springs, nor unseasonable Winters; my Prayer goes with the Husbandman’s; I desire everything in its proper season, that neither men nor the times be put out of temper. (Religio Medici, 1642)

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024