The Music Becomes Him: Mark O'Connor's Journey To 'Americana'

TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview, Part 2

By David McGee

Mark O'Connor: 'One of the interesting things about American music is that it has this broader dimension. It kind of speaks about our time right now, looks towards the future by engaging people and reflects and remembers home.'

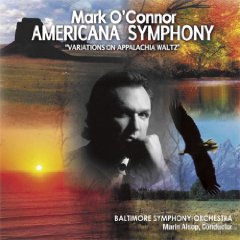

Photo by Joel SiegfriedEmerging from the quiet with a burst of bright brass fanfare, like the sun showing its face to a new day, the familiar theme of "Appalachia Waltz" asserts itself with determined purpose over thundering, ominous tympani. The pattern thus set—of serene interludes conjured by muted trumpets and horns gradually melting into soaring, majestic passages of heroic, spacious dimensions—defines the first movement of Mark O'Connor's long-awaited "Americana Symphony," a compositional triumph marked by the breathtaking execution of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra as conducted by Marin Alsop, and the heightened emotional content of the music itself, inspired as it was by the journey westward of O'Connor's most distant maternal ancestors from Holland, who arrived in New Amsterdam with the first Dutch settlers in 1608 ("Before Jamestown," as O'Connor told a Los Angeles Times writer) and his paternal Irish forebears, who arrived in America in the 1840s, escaping the old country's potato famine. Eventually, all roads lead to Seattle, where O'Connor was born and raised.

"So the journey west, both branches of my family took it, just like so many people," O'Connor told an AP reporter. "And it was this journey out of our cities, towns, into whatever it was to get more land, just to get more breathing room or to get away from something. A lot of this movement was our cultural backdrop to make the music that we have. And so that was a really big inspiration for the symphony."

Indeed. The titles of the Symphony's six movements tell a story in and of themselves: "Brass Fanfare: Wide Open Spaces," "New World Fanciful Dance" (inspired by an Irish jig dance and reflecting, as O'Connor writes in his liner notes, "the beginning of the Appalachian communities when this area was the original melting pot of America"), "Different Paths Towards Home" (liner notes: "The displacement of peoples can be a key component to understanding how American music was derived."), "Open Plains Hoedown" ("With this movement, the hoedown creates what my score suggests as a 'Swift Gallop' across the prairie. I want the listener to 'see' the dust being kicked up by the wagons and horses as the prairie dogs and rabbits do their own hoedown and scurry out of the way!"), "Soaring Eagle, Setting Sun" ("One can hear the exultation. The last great obstacle to the radiant vastness of the West has been overcome.") and "Splendid Horizons" ("The orchestra joins for the final note of the melody before more motivic refrains offered by the winds, strings, brass and percussion bring a final crescendo that joyously celebrates spirit, wonder, renewed optimism and hope for a brighter future."). The vivid evocations of the landscape's beauty and challenge mated to the rich human tapestry O'Connor weaves in passages of quiet reflection and churning emotional outpourings summon comparisons to giants of nationalistic composition such as Dvorak, Smetana, Copland, Grofe, to legendary movie composers such as Elmer Bernstein and Dimitri Tiomkin, and to composers such as Gershwin, who fused classical and pop elements, and Ellington, who brought African-American traditions to bear on his classical compositions.

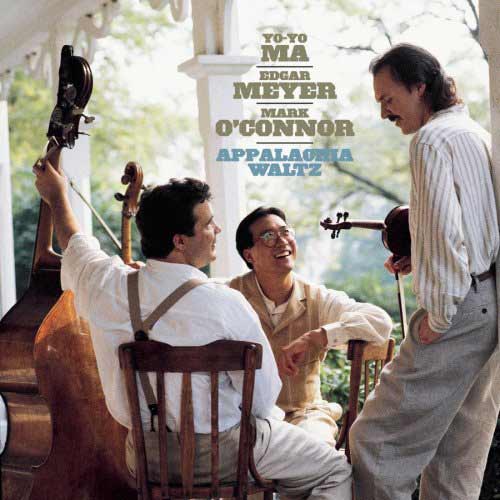

The road leading to "American Symphony" began 22 years ago, when O'Connor, during a recording session break, composed his first caprice for violin. Its completion marked the end of his celebrated session career and the beginning of his commitment to promote a new American classical music embracing folk, country, bluegrass and jazz as part of its vocabulary. In a sense, the "American Symphony" marks the fruition of a personal journey O'Connor embarked upon at that time, which bore fruit initially in 1996, with the release of a trio recording of his "Appalachia Waltz," with Yo-Yo Ma and Edgar Meyer. Some 40 works later—including fiddle caprices, violin concertos, string quartets, a flute concerto, piano concertos, a country-influenced classically oriented reimagining of Johnny Cash's music titled "Poets and Prophets," a folk mass—the durable "Appalachia Waltz" becomes the genesis of "Americana Symphony."

In 1924, at the premiere of "Rhapsody in Blue," George Gershwin described his masterpiece as "a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America—of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, or our blues, our metropolitan madness." Substitute "Manifest Destiny" for "metropolitan madness" and you have "Americana Symphony."

Born (August 5, 1961) and raised in Seattle, WA, living and working during his adult life in Nashville and New York City, O'Connor is undeniably city folk. His speaking voice, forthright and soft, carries no rural inflections, and he's rarely photographed in anything but one of his natty suits (sometimes sans tie, however, for a casual look, as the photos accompanying this article attest). In conversation he chooses his words carefully, speaks with professorial deliberation and keen personal awareness of the intent and meaning of what he's saying, is quick to provide context for every answer and explains his position with lawyerly precision. The artist who is an interviewer's delight for his substantive responses must surely be a harsh taskmaster on stage and in the studio, demanding of others the same rigorous focus he devotes to a performance's nuances.

Thoroughly urban and modern though he be, in his solo work O'Connor has lit out for parts foreign to his own upbringing—the Appalachian mountains, the wars of the American Revolution, the uncharted human and geographic topography of the American west. In the overview, his is an intense, interior odyssey of self-definition, commencing with his brave move away from the work that gave him a professional identity in order to discover and explore the animating impulses of his earliest known ancestors. Their history has become his cause, has become him, in fact, from "Appalachia Waltz" to "The Song of the Liberty Bell" to, ultimately and most majestically, "Americana Symphony." With the unveiling of the latter, O'Connor has become, in Tom Wolfe's phrase, a man in full.

In TheBluegrassSpecial.com's January cover story, O'Connor spoke briefly about the "Americana Symphony," which was released on March 10, calling it "an incredible undertaking," and adding: "I've composed several concerti, but to sustain a full-blown orchestra for that amount of time, plus a lot of percussion, gosh, a lot of detail, it was an incredible feeling." Given that "Americana Symphony" may well be regarded one day as one of this country's great gifts to the classical music canon, as well as being a pivotal moment in the rise of the new American classical music to which O'Connor has committed himself, it seemed appropriate to continue our conversation and learn more about the genesis and evolution of this remarkable work of art, and of the artist himself in his classical incarnation. Lost in all the hubbub about the symphony is that the program is rounded out with a 2003 recording of O'Connor performing his evocative, folk-flavored "Concerto No. 6 'Old Brass'" with the Pro Arte Chamber Orchestra of Boston, conducted by Joel Smirnoff. Something he wrote in his liner notes about the Concerto seemed the proper place to begin discussing the "Americana Symphony."

***

In following your liner notes to "Americana Symphony" and the "Old Brass" concerto, I was struck by your final thought regarding the latter composition, and this would be your final thought in the liner booklet as well. Commenting on "Old Brass" and specifically referencing Frank Lloyd Wright, you say, "I have always embraced the philosophy that once a person impacts their creativity with the natural circumstances which surround them, then there is potential for that art to interface more naturally into the world." It struck me, with reference to the "Americana Symphony," that your natural circumstances are your family history, which so rooted in and inseparable from the history of this land and how it grew. Is that the germ of the idea that begat "Americana"?

Mark O'Connor: I think so. All my creativity is born out in the present day, in my day to day life. And then as I explore and dive into it, I find connectors. I find connectors to the future and looking back into history. More often than not all of my music reflects a sort of tugboat of ideas and history and traditions that I pull along with me. I think one of the interesting things about American music is that it has this broader dimension. It kind of speaks about our time right now, looks towards the future by engaging people and reflects and remembers home. It remembers where we came from. Those are the aspects, I think, that really give voice to what Americana is all about, for musicians and composers to really tap into that kind of spirit and optimism. I think the sense of the beginning and the future really comes into play with creating this kind of music.

Was there a composer whose work inspired the Symphony? It's easy to point to Grofe, or Copland, maybe Elmer Bernstein and Dimitri Tiomkin on the film side. One of my favorite classical pieces and classical pieces is Smetana, who wrote "Ma Vlast" about his own country, which has some interesting parallels to "Americana Symphony" except that his is more focused on the beauty of nature and the land, whereas yours is more a human story. Was there any particular touchstone in terms of another composer who worked in a nationalistic mode?

O'Connor: Well, I definitely took inspiration from some of the great American classical masterpieces, from Copland, everybody's favorites by (Leonard) Bernstein and Gershwin and Ellington. And then more to the point of really developing the concept, I've always enjoyed Piazolla and Bela Bartok and how they interfaced with their own traditions. Many classical composers throughout history have done that. I took my cues from some of the composers from other countries that really embraced and loved their culture. I looked at what we can do here and realized that there's a dropout in this kind of cross-pollination. There's only a few great masterpieces we can hang our hat on, and I wondered why the door wasn't completely shoved wide open in this, why there wasn't a movement towards this kind of ideal? I realized that for there to be a real musical movement, you have to embrace the players, the musicians, and you have to look at the style and the techniques to further the content that musicians need to train in, to really exemplify this idea that there could be a real serious American classical movement. Those are the kinds of things that drive my concerto writing and I wanted to bring that into the symphonic setting continuing with the "Americana Symphony."

The second movement is titled "New World Fanciful Dance," and I know the New World is a reference to these travelers as they go across, but I think of Dvorak here and his "New World Symphony," and how during his time in America he was so influenced by folk music. Is that kind of a nod to him?

O'Connor: Actually a lot of things I do are a nod to Dvorak, because he was one of the great masters that recognized early on that American cultural music had a lot to offer. People sometimes forget that Dvorak was invited to the United States in the late 1800s to help Americans find their own classical music. Out of that experience came the "New World Symphony." In the process of doing that, he couldn't figure out why the people here didn't embrace what they called "plantation songs" back then, the spirituals, of the African Americans, and the blues music. He was very keen on the native people here, too, and was scratching his head as an artist about why people here rejected these cultures and these people in our society and in our music in the classical field. He was really influenced by these things, and he created this masterpiece, but all the while he really didn't like to live here. He missed home, and he left for home immediately afterwards. So the piece that he created for the New World has a bit of a tragic quality to it. The departure for me is sort of what Dvorak did but in reverse, where the tragedy was here as peoples mixed together, but the music is the positive thing that comes out of it. The music and the art forms are the spirit and the optimism that Americans carry ultimately in their heart as they look for a better day in the future.

Do you feel we're in a period similar to what Dvorak saw when he came here, or are we more evolved than we were then? In terms of appreciating our native musics, that is.

O'Connor: I think we've been in this tailspin all along, except for the very few masterpieces, "West Side Story," or Gershwin, when he finally got some critical acclaim from the classical establishment for what he was doing, although he was not vindicated during his time. "Rhapsody In Blue" now has become an American masterpiece. Ellington also fought the forces, too. Here's some of the very top masters in the country, struggling with this kind of an ode to the old Europe mastery, but they had the right idea with the cross-pollination. There's an interesting note that when Ravel came here to speak at Rice University in Texas, in Houston, in the 1930s, he told the audience there that the future of classical music involved African-American music and jazz. People at that time were horrified by that statement and didn't respect Ravel for saying it. We think of him as this unbelievable legend now, but I think people then thought he had spoken out of turn a little bit. But these guys were giving us the memo; they wrote the memo for us—"Here's the blueprint." And we just didn't get the memo completely and kept ignoring it.

When I started interacting with the classical string world 25 years ago, it was very much kind of looked down upon in a way that it isn't anymore. There's a new kind of respect for these things. I was thinking about this earlier today: in my youth, I would play a hoedown, and people that were around me could tell the nuances; they could understand every single way I played every note. I was hatched out of an environment where people really got it; they really appreciated every thing. If I changed one note up, if I put a little emphasis on a phrase, peoples' eyebrows would raise around me, because they would recognize the language in such a way, they were so steeped in it, that any little additional development in the music was noticed and, in my case, appreciated. Then you fast forward into an environment where all this stuff sort of sounds alike to everybody—the discreet qualities between bluegrass and Texas fiddling and Appalachian fiddling, like nobody really knows and nobody really cares.

So I kind of marvel at this personal journey and I want so much to describe musically how these major musical traditions could really bring on a classical musical environment that would be a sustaining—not just a one-hit wonder, "Oh, that's interesting, that's novel, now let's move on."

'A lot of things I do are a nod to Dvorak, because he was one of the great masters that recognized early on that American cultural music had a lot to offer.'How long did it actually take to compose your first symphony?

O'Connor: It took about nine months.

And were you steadily focused on it during that time or were you doing other things and coming back to it.

O'Connor: I was focused for the most part. My career, of course, involves concerts, and so what I would do was have departures and then come back to it. So this was my real creative force for awhile. As a matter of fact, there were at least two months of it when I was working full days and maybe for a month, month and a half I was working sometimes up to 15 hours a day on the symphony. I felt I had such momentum I didn't want to let go of it. Of course that was towards the end of the process. But it was an amazing kind of thing, because there were two years of building up towards it by looking for a consortium of orchestras to premier it. So I didn't actually start composing it until the consortium of orchestras was put together. But during that time the ideas were percolating and I was developing the idea that "Appalachia Waltz" should be the theme, and during that time I settled on a variations symphonic form, which I thought would be really great in several different measures. One is that that's one of my best-known themes and more aptly describes the American classical music that I was striving for. And then second I thought, the variations form of composition—variating themes—is something I've been doing since I was a kid. One of the things I thought was very interesting I discovered about, oh, probably a dozen years ago or more, when I wrote "Song Of the Liberty Bell" for the PBS series on the American Revolution. They ended up using that as the theme song, and during the recording process I tried to adapt that theme of mine in many different settings for the film. I was actually amazed at how flexible that music was, how I could stretch it, change it to a minor key, make it faster, make it slower, turn it into a military march, and on and on. It seemed to withstand the treatment. So I looked at "Appalachia Waltz" as something I felt was very similar, even though people had got used to it being a certain way. I thought, Well, this is going to be a real effort here, pulling this off, taking those phrases that have become pretty well known, certainly to a lot of my fans, maybe to a lot of string players and to classical music followers, and treating it differently. There's a series of techniques that I used to do this, and some are very obvious; some are what you would call "imitative" variations. For instance, the fifth movement, "Soaring Eagle, Setting Sun," is an imitative movement based on a canonic type of composition; the third movement, "Different Paths Towards Home," is a fugue. And with the fugue, just for interest's sake, I actually applied the fugue in its strictest sense for this movement. I used the rules of the original master, Haydn, for the construction of that movement. What I think is most interesting about it is that the "Appalachia Waltz" theme is so American (laughs) that you could apply a centuries-old writing form from Europe to it and it still doesn't sound like Europe.

You might be like me, but every time you hear a composer light into a fugue, you have a feeling like you know where this is coming from. I think with "Different Paths Towards Home" you don't really get that sense. You hear the fugue in there but it doesn't necessarily take you to a displacement of the "Americana" spirit.

What are the demands of symphonic composition as distinct from the other classical styles you've worked in? Was it a difficult transition to that?

O'Connor: I've been doing the concertos now for 20 years, 18 years before I started writing the symphony, and with each concerto I've developed further my own orchestral skill and language and style, and some of the writing has become more complex. With the symphony I was able to have counterpoint sometimes; there's 10 different lines going on at the same time in many parts of the symphony where you can actually trace and follow a thematic counterpoint—its own melody that exists within the form. The idea that there's this linear type of passage work creating the counterpoint is something I've been working on a long time. A lot of keyboard composers—composers that write from the keyboard—tend to sound a little bit more vertical in their harmony and harmonic development using thematic materials. Probably being a fiddle tune player, this engages a different aspect, where harmony comes from how these themes line up throughout the measures. So there's a sense of journey about this music, both conceptually and in articulating the music technically.

Did you compose this on the fiddle?

O'Connor: No, for years now I've been able to compose most of my work off the instrument. What I'm able to do now is constantly think outside the box and not be sort of tied to any one instrument in developing ideas. What's interesting about that is that number one, it frees me up from my own technical limitations as a player, but at the same time I get to utilize what I've developed on the instrument to uncover new ways to create and develop the style and technique that I might never have thought of if I was just playing the violin.

How do you learn to write for instruments that you don't play?

O'Connor: Well, it's interesting, because I think symphonic writers have to have a working knowledge of strings, because the strings are still the basis for the symphonic vocabulary. And if you don't have a real working knowledge for string writing, I fear that could be a handicap. Having said that, I think for myself the percussion, for instance, is also something I'm very familiar with. I trained in percussion growing up. So I actually feature a lot of percussion in this symphony; there's probably more percussion in this symphony than in most symphonies, even today when percussion is much more desired in symphonic works. I have four percussionists plus tympani, so there's five percussionists actually on the floor going back and forth between probably 30 different instruments, including things that you would find in other styles of music, like congas and bongos and ride cymbal. Actually, I've really added the ride cymbal as an orchestral color, much like the triangle, although I use the triangle as well. But for my modern sensibility about Americana, the ride cymbal in my mind replaces the triangle from European writing. So you'll hear that color in all different kinds of cymbals that I call for throughout the symphony.

The brass and winds are the two forces of the orchestra that twenty years ago I had to really study. What I did was I learned about each of these instruments independently of each other and began to be familiar with the tonal aspect of them, the color, the type of impact that they could bring when coming in pianissimo or fortissimo. So my brass and wind writing has greatly expanded in the last twenty years, and I really wanted to feature it. It's interesting, with my concertos I don't really get to write for brass that much because the brass is so loud it covers up the solo. So I used my symphony as a real platform, I guess, to really express a lot of ideas I had about brass writing that I couldn't employ in my concertos.

In the sixth and final movement there's a moment near the end, and you reference it in your excellent notes, where the music falls away and we hear the original incarnation of the piece as it was performed by you and Yo-Yo and Edgar Meyer years ago. Was there a subtle message in that brief passage that reminds us where this journey started, for you as a composer, for us as listeners, and to your own journey to this point in your career? Was that a bit of a personal statement to put that little interlude in there?

O'Connor: Oh, yeah. It's definitely been a huge journey for me, because my composing for that project with Yo-Yo and my playing really opened up a huge success story for me. Also, it's the journey of the "Appalachia Waltz" theme itself. If it wasn't for the Yo-Yo Ma recording, I would have probably never have thought of the idea that "Appalachia Waltz" would be strong enough to be the theme for every single variation of a symphony. So you have to pay tribute to that initial burst of success. I thought about this for a long time, because in the final movement of the symphony the first thing I needed to find out is whether "Appalachia Waltz" could withstand a huge orchestral treatment. Most people feel like the "Appalachia Waltz" piece is very intimate and it's usually played on a solo instrument, and if not, in a duo or trio. What happens to the "Appalachia Waltz" theme when you put forte brass on that refrain? When I started to treat that, I realized I had a finale, a conclusion. I didn't have it all mapped out yet, but I knew it could peak at the very highest volume, and then I could bring it down to the three instruments before the big crescendo and final quotes of the themes that were used during the entire symphony. That's one of my favorite things to talk about, how each desk falls off with the repeating of the phrase at the end, making way for the trio to come out, the initial trio with Yo-Yo Ma and Edgar Meyer, playing my "Appalachia Waltz," which introduced my music to literally millions of classical music listeners.

I like how the subtlest emotional moments, like that quiet trio, carry the most emotional weight. Go back to the "Brass Fanfare" that begins the Symphony, and it's easy to latch on to the big emotions that come with those instruments playing with such strength. I've seen that movement compared to "Fanfare For the Common Man," a great piece, beloved, but with all due respect to Mr. Copland, I think this is a much more subtle piece. The bold emotions rise and fall, but it's those reflective passages, the softer passages that suggest the hope and the uncertainty of what lay ahead on this journey, that seem to carry the most profound emotion. The trio's entrance is such a subtle but telling moment when it comes in at the end.

O'Connor: There's another thing that's so important about the trio at the end and about aspects of the "Brass Fanfare" that I wanted to try to put forward in the composing of this music. That is a very American concept of remembering home. Because the journey is in itself very descriptive of this piece, but that emotional pull you have all the way through, this optimism, is about never forgetting where you came from. You look at my career and my life in music, and I never forgot those early fiddle lessons from Benny Thomasson. So I'm pulling that into this spectrum. Even when I'm creating a "Brass Fanfare," you feel those poignant moments, and that aspect of remembering home. Because the "Brass Fanfare" sets the stage for Americana, the optimism of the west, the wide open spaces, but then you have the dramatic pullback of realizing you're leaving loved ones behind in your journey.

Were you there when Marin Alsop and the Baltimore Symphony recorded the Symphony?

O'Connor: Yes. I was there in the production room. They gave me a great opportunity to get this piece recorded really well. They allowed six hours of rehearsal and then six hours of recording the next day, with a concert thrown in there. So there was ample opportunity to really perfect what I had written on the page. There were some very, very challenging parts to perform to the level I was hoping for. The two what I call "characteristic" variations of the theme, each resolve into a movement that's a jig for the second movement, "New World Fanciful Dance," and the "Hoedown" movement. These were tough to do. One of the things I was hoping for was that the orchestral strings would really drive home the rhythms and would lead the band, as it were. Even though there was a lot of percussion involved. It really happened. It helped the process when I performed with the Baltimore Symphony the season before and I played my "American Seasons" concerto with them. I was with them for a week-we had four performances and two days of rehearsal. And the string players really got to know my style of writing and playing, and I think that helped to bring out a masterful recording. Once again it's so hard to get a great recording of a new orchestral piece today, especially if it's at all challenging music, and I feel like we pulled it off.

'There's a sense of journey about this music, both conceptually and in articulating the music technically.'

(Photo by Joel Siegfried)

You have a brilliant conductor in Ms. Alsop. What difference does that make when you get down to the recording process?

O'Connor: This is the third orchestral album Marin and I have done together, and we've developed a great musical relationship. She is not only a great champion of American music, but she knows my style and has it down. If I was a fine conductor, I would try to emulate Marin. She not only understands what I'm writing and how to bring it out in the orchestra, but if there was ever something I didn't agree with from the conductor's standpoint, say a transition or a tempo or a treatment, I would say something very, very lightly, mention it one time and boom! It's there. It was really amazing. There was very little I would have to say during this recording process, other than just to get the good performance out. She premiered this piece. When I first turned it in, she remarked how my composing had evolved. I think many conductors and musicians, possibly, they see the concerto as something very difficult to do, but nevertheless it's a step up to make a symphonic piece work by itself. With the concertos, if I got into trouble with the form, all I have to do is give myself a few fast licks (laughs) and I create that moment just from my violin, then I'm on to the next part. With a symphony, it has to be so well constructed that the attention of the audience never disappears, and you create and build the momentum. I was so happy that she wanted it to be recorded by the Baltimore Symphony.

The classical world has its hard-core purists, as in the bluegrass world, who don't want things to change too much and no outside influences coming in. But there are also those who are open to those outside influences. Do you have any sense of how it's being received in the classical community?

O'Connor: First, it's unbelievable what has happened to me this year, with the recognition of not only the Baltimore Symphony wanting to record it, but also wanting to perform it right away. They put it at the end of their concert, after Tchaikovsky pieces, after Dvorak pieces. I thought, Now that is really interesting. Because sometimes a smaller symphony orchestra will change up the standard form a little bit, but major orchestras, the masterpieces are their finale; that's what people come out to hear and that's how they get people on their feet. It was very gratifying to me that they would think so much of it that they would end their concert with it. They gave me an insight into what could be the future of the piece. A lot of composers hope they can get as much success as they can right now, and then there might be another wave of recognition when we're much older, and ultimate recognition after we pass on. Depressing to think about. But it gave me reason to believe that after this piece circulates and is listened to on radio and gets written about, things like that, that there could be a real momentum for it. I think my performances with orchestras number over 400 to date, so there's certainly a lot of orchestras, orchestra musicians and personnel in front offices that are familiar with my music. It remains to be seen but there is some good interest at the outset for the consortium process, and now with the Baltimore Symphony performing it so beautifully, who knows what might happen? That's one of the big hurdles for any orchestra, to get a good recording—a recording that you can really hang your hat on and say, "Wow, it can't be played much better than that."

Mark O'Connor discusses the origins and development of the "Americana Symphony."

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024