The Naked Truth From Mickey Raphael

'Unproducing' Early Willie, Unearthing A Classic

by David McGee

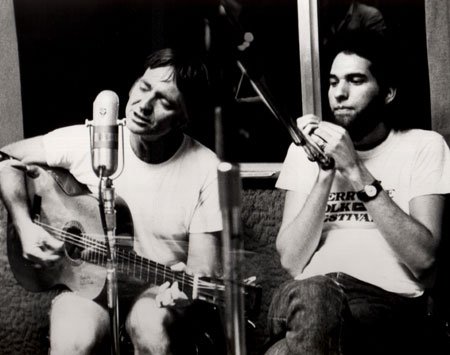

Willie Nelson and Mickey Raphael in the studio, back in the day: 'All you really needed was Willie and the songs, and this core band,' Raphael says of the sessions collected on Naked WillieIt's almost a blood sport among writers to have a go at Willie Nelson's pre-Shotgun Willie (1973) recordings as having done a profound disservice to a great songwriter by burying his lyrical poetry in layers of strings, horns and pop-style background choruses. Willie himself has been somewhat ambivalent about those recordings, made mostly for RCA under the aegis of producers Chet Akins or Felton Jarvis, on the one hand criticizing a system that didn't allow the artist a say in the presentation of the music, but on the other being far more charitable towards Atkins, Jarvis and certainly the stellar cast of A team session players who accompanied him on his late '60s-early '70s work before he relocated to Austin, reinvented himself, and emerged on Atlantic with the aforementioned Shotgun Willie, followed a year later by the Outlaw-defining concept album, Phases and Stages. With the support of Atkins, Ray Edenton, David Zettner (remember that name), Pete Wade, Jr., Grady Martin, Jerry Reed and Chip Young on guitar; Bob Moore, Norbert Putnam and Roy Huskey Jr. on bass; Buddy Harman and Jerry Carrigan on drums; Glen Spreen on organ and harpsichord; David Briggs on piano; Jimmy Day and Buddy Emmons on steel guitar; and Charlie McCoy on both guitar and vibes, and some startlingly literate, ahead of their time original songs, Willie cut a host of remarkable records in a futile attempt to establish himself as a solo artist after having already made his mark as a songwriter, thanks to the likes of Patsy Cline and Faron Young. And that precisely was the point—they were going for commercial hits, and the pop-oriented "Nashville Sound" had supplanted the unadorned basic country combo as the mainstream mealticket, for better or for worse. It worked, and then some, for Patsy, and for Jim Reeves, but not for Willie, or for Waylon either.

In recent years, domestic labels have afforded us a glimpse into what Willie was talking about by releasing collections of his songwriter demos (Crazy: The Demo Sessions, and 54 Songs: Songwriter Sessions being the gems of the lot), almost all of them pared down, small combo bursts of transcendent artistry. Now comes another illuminating gap-filler in the Willie story by way of RCA/Legacy's Naked Willie, a collection of 17 songs recorded for RCA between 1966 and 1970, from which Mickey Raphael, Willie's redoubtable harmonica player of nearly three decades' standing, has "unproduced" the pop embroidery that spruced up the original recordings for popular consumption. No strings (except for some hushed ones on "I Let My Mind Wander," unable to be removed from the original mix without eliminating the instrument into whose mic they had leaked in the "live" studio setting), no horns, no Anita Kerr Singers shadowing Willie's vocals. It might be the album of the year, this Naked Willie, because, truth be told, it's going to take some kind of effort for another artist to come up with 17 songs of this quality, played with this degree of authority and nuance, and rendered vocally with this magnitude of conviction and subtextual insight. Willie is at the top of his game here, as a writer and singer. In addition to its piercing accounts of love rent asunder, the tunestack includes Willie's first pronounced bit of social commentary. The dark, brooding "Jimmy's Road" charts, in a devastating 2:37, a boy's path from childhood to young adulthood, and from there, to the battleground, "where Jimmy learned to kill"—and here Willie draws out the word "kill," to press the point—"now Jimmy has a trade/and Jimmy knows it well, too well," to "Jimmy's grave." Recorded in 1968, the antiwar song was spurred by Willie's anger at his guitarist David Zettner (described by Chet Flippo in his liner notes as "a true gentle artist in the truest sense of the word"), being drafted and sent to Vietnam.

But the overarching theme is one of love gone awry and a solitary man chasing after the reasons why. "My lonely heart wonders," Willie sings over the oddly cheerful, music box chiming in "I Let My Mind Wander, "if there'll ever, ever come a day/a day when I can be happy/but I can't see no way/'cause I let my mind wander..." In the bluesy swagger of "If You Could See What's Going Through My Mind," he leaps into the metaphysical in his lonely contemplation, with "If you only knew the values of unknown/and if you could see transitions going on/and if my lips could speak the words/the truth you'd find/if you could only see what's going through my mind." Who was writing country songs referencing "the value of unknown" in 1968? In one of his most beautiful and unsettling songs about abject loneliness, "The Ghost," he begins with the casual observation that "the silence is unusually loud tonight," sung offhandedly with no greater emotional investment than a comment on the weather, which turns out to be the setup for a chilling premonition of a literal, onrushing haunting: "The strange sound of nothing fills my ears/Then night rushes in like a crowd of nights/And the ghost of our old love appears...The strange world of darkness that comes with the night/Grows darker when it walks my way." On the rafters-shaking gospel number that closes the album, 1970's "Laying My Burdens Down," he begins, "I used to walk stooped from the weight of my tears/I just started laying my burdens down/used to duck bullets from the rifle of fear...," conjuring an image of a man undone both physically and psychologically by his love wars until blessed with a spiritual epiphany and reclamation that he goes on to celebrate unabashedly as the song develops.

Naked Willie is a treasure trove of amazing lyrics that stand out more so now owing to Willie's voice carrying the weight of the performances instead of being subsumed in the original arrangement. At the same time, you can hear in what is now a traditional country arrangement of "The Party's Over" (long-time viewers of Monday Night Football will recognize this as Don Meredith's on-air sayonara to the losing team) that underneath all the froo-froo was the Willie we came to know in the '70s, with a tough combo at his command and Buddy Emmons crafting a wonderfully compatible steel guitar solo behind the vocal. In addition to showcasing Willie at his best, Naked Willie's content offers Willie-philes plenty to chew on in terms of foreshadowing: a previously unissued non-album track, the buoyant "Bring Me Sunshine," hints at the classic pop breakthrough of 1981's Stardust; the devastating narrative and sound of "The Ghost" is a bridge to 1974's Phases and Stages; the Spanish flavoring and eerie ambiance of "Following Me Around" links us to 1998's Teatro. Rarely has a reissue been so rich on so many levels, and yet totally accessible to the casual fan unconcerned with wonkish, musicological pursuits but merely seeking a stirring musical experience.

Checking In With Mickey Raphael

'I think Naked Willie stands on its own as a classic Willie record, even if you weren't familiar with the originals'

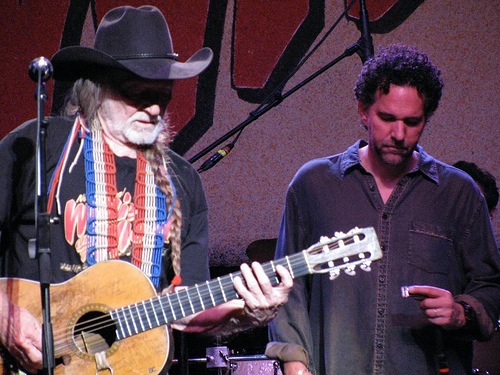

Mickey Raphael (right) in his usual position at Willie's side, on stage: 'Naked Willie stands on its own as a classic Willie record, even if you weren't familiar with the originals.'We caught up with Mickey Raphael while he was on the road with Willie and chatted about the making of Naked Willie and what surprises, if any, greeted him upon digging into the master tapes of the RCA sessions revisited for this "unproduced" release.

When you guys went back to this material, how was Willie feeling about the original recordings?

Mickey Raphael: It's funny. I did everything myself and kept him updated. It was my idea. So I came with it to him and I said, "I'm not going to say anything negative about these guys. I love these records"—because that's what really turned me on to Willie, listening to these songs and these records. But being with Willie for all this time, his mantra, if you had to pick one thing about what Willie stands for artistically, it's that less is more. So I'm thinking as I listen to these things, These are great songs and I really love the production. But I just wanted to look at it through another lens. And I never asked him, "Did you like the originals?" I wasn't looking for anything negative about it. At the time that's what was going on, that's what they needed to do. Everything that was recorded in Nashville at that time was recorded like that—the "Nashville Sound." But I still think the songs stood on their own. He's not necessarily going to go back in and record these songs, because they were done once. So I told him, "I want to go in and see what the multitracks sound like without the strings. I think you were a strong enough writer back then that you didn't need all this stuff." And I wanted to prove the theory, prove him right. Willie would never say to Chet, "I don't like this." At that time anybody was lucky to be recording, and that's when he was building his own identity and thinking, or going over in his mind, that he didn't dig the strings-or he might have said, "This is really cool." When I played him the finished project-and I kept him abreast of what was going on but he didn't hear it until it was done-he said, "Aren't these the originals?" You know, he felt so comfortable with it. He asked, "What'd you do?" Then I played him the originals, and he was like (ruefully), "Oh, yeah—I remember that." Again, I didn't ever put him in a position to say anything negative about Chet or the other guys. They made some great records. I just wanted to prove that he was right, that all you really needed was him and the songs, and this core band.

Willie himself has pointed out that everybody was seeking a hit. Willie wanted a career beyond being a songwriter. This was business. They were taking the best shot they knew how.Raphael: Right. Do you think radio would play something that didn't have these strings? It's precisely what they wanted. Perry Como, Andy Williams, Frank Sinatra, all these guys were selling tons of records. Besides being great artist, guys like Chet Atkins were also good businessmen. It's the music business, and they had to sell records. They couldn't release a great demo, or something so bare. And they wanted country music to change, to be a little more cosmopolitan. Before that, banjos and fiddles were the predominant instruments, and I think they wanted to refine that a bit. But right, they had to sell, and that's what people were buying at the time. I figured it's safe now because everybody's dead, and we can go back and say, Okay, these songs are strong, the players are great.

In going through the original productions, did anything surprise you about what you heard?

Raphael: There was some great playing that was not heard on the original tracks, or was so covered up. One that comes to mind is "Laying My Burdens Down," when Grady Martin is taking this great solo at the end. On the original there's a chorus, the Anita Kerr Singers, singing, "Just got to lay my burdens down," over and over again. When I took that off there's this great guitar that goes on for 20 seconds or more. I faded out the song on this great guitar solo. I thought, People really need to hear Grady. When I first met Eric Clapton, he came by the show, and Grady was playing guitar with us. He was retired from the studio, but he was playing in the band for about 10 years. So I met Eric, and asked him if he wanted me to take him to meet Willie, and he said, "No, I want to meet Grady."

On that same point, on the song "Following Me Around" there's a Spanish flavor that's carried by the horns on the original, but when you stripped that out David Briggs's piano is doing that and it's beautiful—it's almost like church. It has the same flavor and you don't miss the horns at all.

Raphael: Yeah, and the horns reminded me too much of The Dating Game theme. That's when Danny Davis was producing him, and horns were his forte; he was really great at that. Not to say there's anything wrong with that original song, but-it takes on another life when you bring David up, who was pretty much covered up in the original.

Did any of Willie's performances surprise you? Did you learn anything about him from these performances from the late '60s, early '70, that wasn't already apparent to you?

Raphael: I like the way his voice sounds. It's a little deeper, a little richer now, but I love the tone of his voice. And it may just be because that was my entrance into Willie, the first thing I heard that attracted me to him. "Follow Me Around"—I had never heard that song before until I found it on a Bear Family collection of his RCA stuff. He was writing so good and playing—he took the solo on "Sunday Morning Coming Down," and that might have been the first time they let him play guitar on any of this stuff. It's not that they didn't let him; but with Grady, and Chet, and Chip Young and all these other players, whom he loved, his attitude was, "Why should I play when all those other guys were there?" But I think I got a great guitar part on "Sunday Morning Coming Down."

You mentioned his voice. It has a lot more presence on the Naked Willie recordings than on the original productions. Is that a product of everything being stripped away or did you do some sweetening?

Raphael: We did some stuff. Tony Castle is the engineer I used, he's got a great ear, and again didn't want to make it too modern. But we wanted to warm up Willie's voice, to make it more present, to bring it up in the mix, to make it the predominant instrument that you hear. Then with some studio tricks we warmed his voice, fattened it up a bit with some modern-day technology.

How long did you pore over these tapes and how long did this project take from beginning to end?

Raphael: Once I got the tapes, I went to New York for a day with Rob Santos, who's head of A&R at Legacy, just to search. We got the mulitracks and went into the studio to listen to them to see if it could be physically done. When we decided it was possible, we got about 35 songs, put 'em on a hard drive-transferred the multitracks to a hard drive—and took 'em to Nashville. Once we got in the studio we tried to suss out what songs we could work on. A lot of them we couldn't touch because the strings were in Willie's vocal, or it bled into the piano, and I didn't want to start fixing stuff—take the strings out, then we lose the bass track. I could have got Bob Moore to play it again, but I thought I'd lose the integrity of the project if I did that. So, start to finish, 17 songs, it was probably three weeks. I budgeted two songs a day when I set how much studio time I needed. But that was really cutting it close; I needed a song a day. It was my first project too, to be doing this, and I worked poor Tony to death. I relied on him a lot. We worked probably 12 hours a day, very tedious work, too.

It was cool to have these tracks at my fingertips so we could bring up Willie's voice and say, "Listen to this. Listen to how he's singing." Or, "Listen to how Grady's playing" or "Listen to how Chet's playing." For awhile there we probably wasted some time just soloing every instrument and listening to how great the guys were playing. Especially Charlie McCoy-

One of your heroes.

Raphael: He's totally my hero. But he didn't play any harmonica on these sessions. He played vibes. I said, "Make sure you don't lose the vibes. You can barely hear him in the original. Let's pull him up."

You mentioned a total of 35 songs you were looking at. Is there enough salvageable remaining that you could do another volume if you wanted to?

Raphael: Possibly. It was so time-intensive. I wanted to bring it in under budget and just do good for my first attempt at producing. There might be enough. But again, I don't want to go in and replace anything. I want to keep everything as original as possible. Everybody was recording at the same time, so the strings were leaking into all the open mics, or when they were doing three- and four-track recordings, they'd record on three tracks, mix it down, bounce it over to one-track. So you'd have the strings and the piano and the bass maybe all on one track. So to dump the strings I'd have to lose the bass and the piano. I could have re-recorded that, but I didn't want to do that.

What did Willie think of the finished product?

Raphael: He loved it. He said, "This is what it might have sounded like had I been producing." Might—I said, "Are you saying this is what it would have sounded like?" He said, "No, let's say this is what it might have sounded like." Like if we were to cut any of the songs again, this is what he would be doing. I'm hoping somebody will listen to it and go back and compare it to the originals. I think it stands on its own as a classic Willie record, even if you weren't familiar with the originals.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024