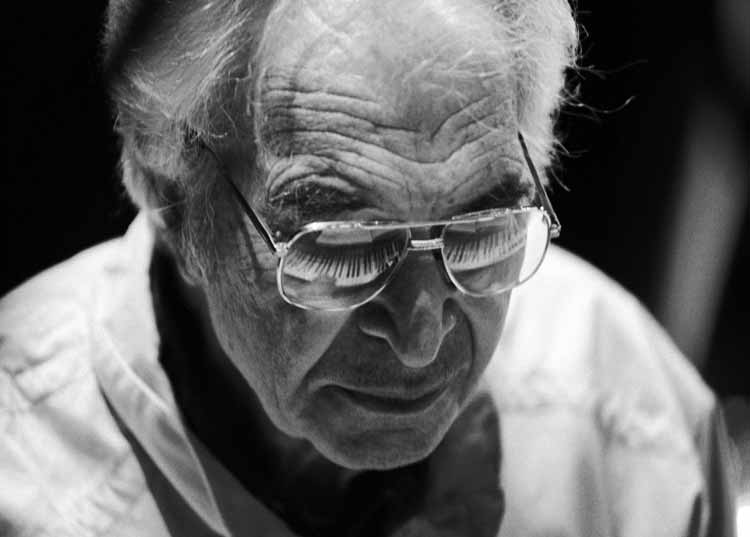

Dave Brubeck, of whom the author writes: "I have long admired and respected Dave Brubeck as a man and as a musician, as a force for change in human relations and as a man deeply committed to the roots of jazz, who nevertheless looked to expand on its root vocabulary by referencing his deep love for and knowledge of traditional and modern western classical music, and he was always looking to introduce polytonal, polyrhythmic and contrapuntal elements into the collective dialog. And for this, at the height of his popular breakthrough, he had to eat a lot of politically correct shit from pseudo-hipster, pseudo-liberal jive artists masquerading as 'critics' for having the effrontery to be both white and popular."An American Treasure

In Praise Of The Real Ambassadors and The Integrity of Dave Brubeck, Inextricably Linked and Oh-So-Right For the Times

By Chip Stern

The Dave Brubeck Quartet in its second iteration, when the great pianist-composer and his alto saxophone doppelganger Paul Desmond were joined by the great bassist Eugene Wright and drummer Joe Morello, was one of the most esteemed recording and performing ensembles in the history of jazz, and most of you are undoubtedly familiar with their famous 1959 recording Time Out, which introduced a number of memorable jazz standards in what were then considered rather esoteric time signatures.

I have long admired and respected Dave Brubeck as a man and as a musician, as a force for change in human relations and as a man deeply committed to the roots of jazz, who nevertheless looked to expand on its root vocabulary by referencing his deep love for and knowledge of traditional and modern western classical music, and he was always looking to introduce polytonal, polyrhythmic and contrapuntal elements into the collective dialog.

And for this, at the height of his popular breakthrough, he had to eat a lot of politically correct shit from pseudo-hipster, pseudo-liberal jive artists masquerading as "critics" for having the effrontery to be both white and popular. The one time I had the opportunity to interview this gracious gentleman, I got the distinct impression those jabs and put-downs still hurt decades later.

Never mind that approaching the age of 90, Brubeck is still hard, still out there, still making gigs and turning out superb recordings for the Telarc label, such as a wonderful solo piano recording from 2004, Private Brubeck Remembers, which reprises the music of a generation of young men who went overseas during World War II and left their sweethearts behind, never sure if they would ever see each other again. It manages to balance ambiguity and nostalgia, throwaway tunes and real classics in a way that is at once quite touching and swinging, without ever indulging in cheap sentiment?wonderful performance and wonderful sonics.

Never mind that four of his six children (pianist Darius, drummer Dan, trombonist-bassist Chris and cellist Matthew) are excellent musicians in their own right, and often collaborate with their father.

Never mind that on one hand you can clearly hear the likes of Jelly Roll Morton, Willie "The Lion" Smith, Fats Waller, Count Basie and Milt Buckner echoing about in Brubeck's deeply informed historical perspective of the American piano.

Never mind that in the extensive body of work for Fantasy Records (which he helped found) that precede his classic quartet days, some of his experiments in modern music were of a magnitude and vision that you could subsequently trace his influence on the likes of such avant gardists as Cecil Taylor.

Never mind that along with Max Roach, Brubeck's musical sojourns beyond common time have led to generations of musicians for whom complex metric transitions through different time signatures are no longer a daunting challenge, but part and parcel of the modern musical vocabulary.

Never mind that countless jazz musicians, including no less an innovator than Miles Davis, have turned to such superlative Brubeck jazz standards as "In Your Own Sweet Way" and "The Duke," and found something of themselves in their lilting melodies and sophisticated harmonies.

Never mind that he fronted a fully integrated Army band, that performed all over Europe for a decidedly segregationist American Army, during World War II.

Never mind that the classic Brubeck Quartet featured a virtuoso African-American bassist, Eugene Wright, who brought a degree of rhythmic and harmonic sophistication that was at once both cutting edge and firmly rooted in the Walter Page/Count Basie rhythmic tradition, nor that Brubeck would routinely turn down lucrative bookings at colleges and performance venues where any semblance of segregation was tolerated.

Never mind that Dave and his wife Iola Brubeck always championed human rights, never more so than when they wrote and produced a jazz operetta for the great Louis Armstrong that was an alternately satirical/inspired call for liberation and freedom and humanistic values, coming hot on the heels of Brown V. Board of Education, when Jim Crow America was still lurching its way along in the days before the Civil Rights and Voting Rights legislation of the mid-'60s.

The Real Ambassadors was recorded at Columbia's acoustically splendid 30th Street Studios in the fall of 1961, and last enjoyed a commercial release on CD in 1994 for the Sony Legacy label (I was privileged to speak with Dave and pen the liner notes for this re-issue): besides Louis, it featured a Brubeck piano trio with Eugene Wright and Joe Morello; the Louis Armstrong All-Stars; the great vocalist Carmen McRae and the remarkable vocal trio Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. In part it referenced the hypocrisy of employing American jazz musicians such as Louis Armstrong as goodwill ambassadors, capable of dissipating anti-American student riots on their State Department tours (as Dizzy Gillespie did back in Greece during 1956) while back at home in the land of the free, African-Americans endured legal apartheid. In 1962, there was a performance of "The Real Ambassadors" at the Monterey Jazz Festival, but it has never enjoyed a public performance since, although the Hartford-based jazz vocalist Dianne Mower has launched a web site dedicated to bringing Dave & Iola's work to Broadway.

Still, while this 1961 recording features a wonderful aural qualities to complement its superlative arrangements and performances, the CD is inexplicably out of print, although it is available from Amazon dealers and as an mp3 album download, so keep an ear out for it. In the meantime the Brubeck CD I am going to hip you to, that has been in heaviest rotation as a reference recording every time I am looking to A/B audio gear (or am just down for some musical pleasure), is The Dave Brubeck Quartet at Carnegie Hall (Sony).

In his recollections of this showcase gig from February 22, 1963, Brubeck relates how it occurred smack dab in the middle of a newspaper strike, and the band wasn't sure anyone would even show up. But they ended up playing before a packed house, and from the moment they launched into their opening number, "St. Louis Blues," it was clear to everyone on stage and in the audience that the band was on fire. But their fire is informed by the unmistakable grace and relaxation of a band whose skills have been honed over hundreds and hundreds of live gigs and recordings to the point where they are able to create spontaneous responses and collective orchestrations in the moment that transcend all of their intellectual preparations and conscious decision-making..what Art Blakey characterized as "direct from the creator to the artist to you..." That rarefied state where a band looks forward to getting lost, so that they can share the magic of collectively finding their way out of the darkness and back into the light (and vice a versa)?a process of discovery where musical comrades share a fresh and unexpected perspectives on familiar terrain.

You can feel that vibe on every track and the recorded sound only amplifies the emotional intensity and aw shucks swing with which the band gets in and out of every situation. There is a lovely balance between the stage sound and the hall sound, which to me is particularly powerful on their reading of "Blue Rondo a la Turk" where the band emerges from the jagged formality of the famous 9/8 set-up into a glorious medium-up pulse imbued with a blues feeling, and man is Paul Desmond ever swinging, every melodic phrase browned and burnished in clarified butter and floating dreamily over the a deliriously laid back Wright/Morello stroll. You can hear Desmond reveling in how the sound of his saxophone comes back to him from the hall, and in a sense the ambience of the hall is dictating his tempo; you can hear the enormity of that sound as it projects into the farthest tiers of the hall, and over a couple of choruses the saxophonist gradually breaks into purer and purer vocal exhortations, as he toys with the outlines of an old popular song whose melodic outlines I recognize but whose title I cannot call up for you; still I can clearly apprehend the lyrics (and so can Brubeck, giving Paul an audible amen) as Desmond stretches the words like taffy and seems to intone "...on olllllllllddddddd Broaddddddddwaaaaaaay..." before tying things up with a surprisingly down home testimony. Brubeck then digs deeper into the groove beginning with big two-handed chords, then down-shifting into teasing little single-note blues phrases, introducing subtle little polytonal touches as Wright and Morello settle into an elemental shuffle (and you can clearly dig the palpable weight of Wright's acoustic bass, the sparkle and presence of Morello's top cymbal and snare as they move air). As Brubeck begins to double up rhythmically into a very powerful evocation of his stride roots, they echo his emotional and physical complexity, bringing things to a dynamic catharsis.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet, 'Blue Rondo a la Turk'— Part 6 of a lost Australian performance of Dave Brubeck Quartet hosted by Digby Wolfe. The film was saved from destruction in 1984 and now is with the Australian National Film and Sound Archive.It is a conclusive moment, but the band rewards the audience with a very loosey-goosey, near eastern-flavored coda on "Take Five," and as on the band's other readings of the Time Out and Time Further Out repertoire (such as an utterly charming version of "Three To Get Ready" which leads into the first intermission), their interpretation of this material has grown far less formal and self-conscious, altogether warmer and more confidently swinging, and the manner in which the recording captures Morello's melodic cross-rhythms and accents on the toms is just remarkable (as is the drummer's wide-ranging series of rhythmic events on his feature showcase, "Castilian Drums").

Rarely have rhythm instruments been portrayed with such presence and warmth (dig Wright's bass on his "King for a Day" feature), nor has a live recording maintained a better, more natural balance between piano and drums (though good microphone work notwithstanding, clearly much of that balance derives from Brubeck's and Morello's hands and ears). But with the passing of time, I find myself returning more and more to the band's elemental workout on "Pennies From Heaven," where you can hear the band's deep grounding in and love for the Ellington/Basie tradition, and where the levels of interplay and swing are damn near telepathic—four men swinging and singing as one. I particularly love the way Brubeck deconstructs and abstracts the theme, like a cat toying with a mouse, before teasing Morello into syncopated give and take with some of those joyous, resounding, big band chordal flourishes. In listening to this track it occurred to me that in the history of jazz there have been few artists who less deserved to be pilloried with the pejorative "white boy" than Dave Brubeck. Yes, yes, yes, we are all aware of the western Classical and 20th Century devices Brubeck loves to deploy in his music, but on track after track from this concert it is patently clear that Brubeck's connection to the African-American tradition—not only of the big band and stride schools but of the most sanctified of church and down home blues—is deep and devotional. (When was the last time you saw that in a Dave Brubeck review?) And as they take the theme out, Brubeck and Desmond engage in a bit of elegant contrapuntal whimsy before settling on a "shoot the ticket to my John Boy" closing right out of the Basie/Jo Jones reader. Damn...now that's jazz—one of the greatest concert recordings ever, by one of America's greatest bands.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet at Carnegie Hall should be a stocking stuffer for all seasons. Rarely has a concert recording made the sense of venue, the shared feelings of inspiration, the give and take between band and audience seem more live and in the moment. So what exactly are you waiting for, Pilgrims, your own personal stimulus plan? Only five more shopping months till Xmas.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet, 'Take Five,' 1961

Dave Brubeck, Paul Desmond (sax), Joe Morello (drums) and Gene Wright (bass)

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024