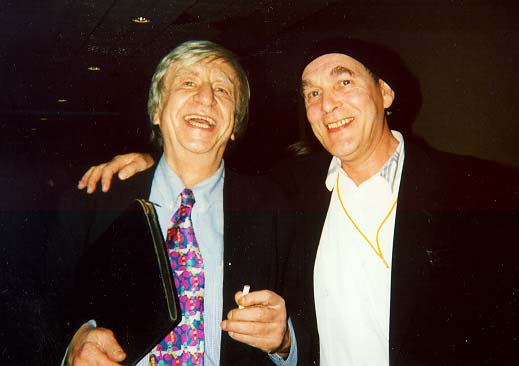

Heinz Edelmann (left), Website Design for the animated Beatles film Yellow Submarine, with Neil Aspinall, head of the Beatles' Apples Corp., in Liverpool attending the world premiere of the refurbished version of Yellow Submarine, August 30, 1999'And He Told Of Us His Life In The Land Of Submarines'

Heinz Edelmann

June 20, 1934-July 21, 2009Heinz Edelmann, an influential illustrator and graphic designer whose psychedelic, pop art vision of Pepperland for the Beatles' 1968 animated film Yellow Submarine brought both the spirit of the Swinging '60s and its trippy (some might say "acid-drenched") graphic art together to create one of the decade's most striking, and enduring, artifacts, died of heart disease and kidney failure on July 21 in Stuttgart, Germany. He was 75. For the film, Edelmann created the mise en scene for a classic battle of good (the Beatles) versus evil (the Blue Meanies, et al.) in Pepperland, "an unearthly Paradise, eighty thousand leagues beneath the sea," a world apart from the rest of civilization (including, notably, the dirty, dingy, decaying London of the movie's opening scenes, which include a memorable series of eerie, bleak images accompanying the song "Eleanor Rigby") accessible only via a yellow submarine and populated by bloated, authoritarian villains of a certain hue (Blue Meanies), of towering, rail-thin, expressionless hit squads of Apple Bonkers (who crushed the color out of the world by dropping giant green apples on the populace), and a malevolent, laughing Flying Blue Glove killing machine. During production and even after the film's release, rumors abounded that Peter Max, whose psychedelic art had made him the poster boy for the style and who had befriended the Beatles, had created the artwork for Yellow Submarine. In a 1993 radio interview, Edelmann dismissed these rumors, and a few others, in one fell swoop, commenting, "Well, I've heard rumors. But, you know, if one goes by the books about official history, there have been hundreds of creators of Submarine. And at that time a lot of animators also claim to have taken part in the production who did not come within a thousand miles of the studio."

To the general public Edelmann was inextricably linked to Yellow Submarine, but to those in the business and art of illustration and graphic design, he was respected for his original vision, equal parts Impressionistic and Expressionist, and for the wry humor and irony infusing his creations. His friend Milton Glaser, himself a graphic designer of note, told the New York Times Edelmann "became famous because of his work on Yellow Submarine, but that celebrity actually obscured his real talent and imagination."

Born in 1934 in the former Czechoslovakia, Heinz Edelmann studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Dusseldorf, one of the most progressive schools in postwar Germany. After graduation, he began working as a freelance designer, illustrator, animator and teacher. He created posters for the Westdeutscher Rundfunk radio station in Germany, book covers for the Klett-Cotta publishing house in Stuttgart and editorial illustrations for Twen, a high-concept, graphically lavish magazine for teenagers. He also illustrated the first German edition of J. R. R. Tolkien's Lord of the Rings. In time he became more vocal about expressing his opinions on a variety of social issues, sometimes through his art (his visual essays for the Sunday magazine of the newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung sometimes made pointed references to cultural and political matters) and in the design classes he taught at the Stuttgart Academy of Fine Arts, where the Times reported students describing Edelmann's lectures as consisting of "metaphysical monologues examining links among the arts, literature, Asian mythology, graphic design and the dumbing down of youth."

In 2007 Edelmann published a graphic novel, The Incredible. One critical trade review found author and subject matter out of step with the times, noting, "German illustrator Heinz Edelmannn, born in 1934, refuses to take part in the 21st century. He lives in 1999, indefinitely. In his graphic novel The Incredible, Edelmann records bombs dropping and media battles raging, unaware of their political or economic reason, and all in what might have passed for a breezy style circa 1955."

In a 1993 interview with Dr. Bob Hieronimus posted at www.21stcenturyradio.com, Edelmann discussed in depth the making of Yellow Submarine, describing a chaotic production process involving hundreds of artists that he oversaw and a punishing deadline that drove him to the brink of exhaustion, leading him to conclude that "the entire Submarine experience was a complicated, long dream." Looking back, he said, "In a way I don't relate Submarine to my life anymore. This was done by a completely different person. At one point, I had food poisoning and I went around not being quite myself and there were other projects being discussed at that time. Brigitte Bardot was interested in hiring me as designer for a projected musical extravaganza. And at that time I was barely conscious because I had a temperature of about 41 centigrade. And I do remember sitting next to Madame Bardot in a Roll Royce. And she was saying, 'Mr. Edelmann, you are a great genius.' But I do not relate that to me."

Heinz Edelmann was given a Masters Series exhibition at the School of Visual Arts in New York in 2005. He is survived by his wife, Anne, a daughter, Valentine, who lives in Amsterdam and is an illustrator, and one grandchild.

***

'The Meanies represented a symbolic version of the cold war. And originally they were the Red Meanies. But we didn't have enough red paint in the place. So they became the Blue Meanies.''The Production Was One of the Most Chaotic in the Entire History of Film'

Excerpts from an interview with Heinz Edelmann, October 22, 1998, conducted by Dr. Bob Hieronimus for Baltimore's Best 21st Century Radio

You were the artistic director of Yellow Submarine. What did that entail?

Heinz Edelmann: At that time I was the graphic designer working in Germany, and known in professional service for my poster work. I also did contribute as a regular illustrator for a magazine that was known for its avant garde designer illustration work. And this was looked at or read abroad. And somebody on the Submarine team happened to be familiar with my work and just called me up.

Who was that?

Edelmann: That was Charlie Jenkins, the Website Design in charge of the special effects who doesn't get mentioned nowadays. He was responsible for the many of the more interesting parts, like the "Eleanor Rigby" sequence, which we worked out together.

Most Americans are under the false impression that Peter Max illustrated the film. Are you aware of this misunderstanding?

Edelmann: Well, I've heard rumors. But, you know, if one goes by the books about official history, there have been hundreds of creators of Submarine. And at that time a lot of animators also claim to have taken part in the production who did not come within a thousand miles of the studio. There's a book called The Twentieth Century Cultural Calendar, which has the major artistic highlights listed for this century until the eighties I suppose. And this says Submarine had been designed as a joined effort by the cream of British artists.

And who is that supposedly?

Edelmann: Well, the cream or whatever, I suppose, knowing that I did it, I suppose then I must be the cream of British artists.

Heinz Edelmann, 1968: 'The entire Submarine experience was a complicated, long dream.'

How do you feel about someone else being credited with this cultural masterpiece? Now, I'm aware that you are probably a little embarrassed at my calling it a cultural masterpiece, and I apologize for that. But to us and to many Americans, it is considered a cultural masterpiece.

Edelmann: Thank you, I mean that's a great compliment. But you know, as a working artist and illustrator, one should not think in those terms. As Picasso once said, "An artist stops being an artist the moment he becomes the connoisseur of his own art." You know, I never think about what I do afterwards. The moment it's out of the studio it's delivered and printed I forget it, I rarely look back at my work and I never sign my work either.

What kind of script or direction were you given before you started designing the characters and scenes?

Edelmann: Well, one has to go back a bit in history to what is not very well known now, but Submarine was not the first animated Beatles film. The same producers did about 70 five-minute films. Each built around one song with three minutes of mild domestic comedy around it; these were produced, as far as I know, in the East, in Japan, but mostly in England, where animation was available at reasonable prices. TVC of London, the company that produced Submarine, which also did most of the other shorts, was commissioned to do the feature film, which would be sort of the catch of the series. And the series was, of course, conceived and written in the quite early days, when the Beatles were still very much connected with Liverpool.

So all the action in the shorts was a sort of local domestic comedy. And the original script followed up on that along the same lines. But by '67 the Beatles had evolved into something quite different. So we all felt the original script did not do justice to what the Beatles had become. I did know the Beatles—who didn't? And I was familiar with the music, but at that time I was in my first Miles Davis period. But, what I did enjoy were John Lennon's books.

In His Own Write and The Spaniard in the Works.

Edelmann: And I felt the script we were supposed to be working with did not do justice to what the Beatles were actually becoming. So you know from the original script, I think two names were kept. The name of "Old Fred" occurs in a sort of maritime story. One obviously had to have some crafty old salt. And then the name of the Boob character, at least what was kept was that. There was a list of the music that should be in the film, and it was determined that "Nowhere Man" should be in the film. And that the Nowhere Man should be called the "Boob."

Yes, J. Hillary Boob Phud.

Edelmann: He was just called the "Boob." Without any first name. And this is what survived from the first, second and the several versions of the script that got weirder and weirder. And there was one that concentrated on the marital problems of Mr. and Mrs. Old Fred. In which the submarine only appeared as a ship in a bottle. It did get weirder and weirder. As production time drew close and the final presentation, I was given the brief to do Davey Jones and to illustrate Davey Jones in Davey Jones' Locker, together with some mermaids, and this was on a Friday afternoon when everybody else went away for the weekend, which was at that time religiously observed in London.

And there I was sort of feeling depressed and I was supposed to have one assistant come in on Saturday to help me on the coloring work. Now of course, I was not very happy with doing a Davey Jones. And also, I've never done a drawing of a mermaid in my life, and I hope to go to my grave without ever doing one. And so I was working Friday night 'til Saturday and feeling frustrated and just wanted to go back home. And just as a point of professional pride, I did not want to leave and to resign without at least having proposed something else. The animation directors had been discussing roughly a story of villains. I just sat down and thought, Well, obviously I couldn't do Davey Jones, and I didn't want to any mermaid. So I thought, What would I like to draw? And I built a sort of outline around that, and developed the characters.

‘Ad hoc, ad lock and quid pro quo; so little time, so much to know’: Yellow Submarine, the ‘Nowhere Man’ sequence—the ever-rhyming Jeremy, ‘a boob for all seasons,’ first engages The Beatles, then is adopted by them.From this standpoint then, you actually were creating the script. To a degree.

Edelmann: Obviously the Liverpool domestic situation did not apply anymore. And if the film was to be about the Beatles and a submarine, it could have been a submarine mysteriously appearing in Liverpool, which would have made it a latter day Captain Nemo story. The lyrics went against that because it does explicitly say in our Yellow Submarine, not in somebody else's Yellow Submarine.

So the idea was to have the Beatles in the submarine, but for Captain Nemo's scene to be a bit much. And the conning tower would have become pretty crowded. So I thought the obvious solution would be to have the submarine belonging to a third party. And also, what would be interesting, if not the submarine itself, would be the way from point A to point B and what was going to happen when they arrive.

And for this I just drew up all sorts of surrealistic villains I could think of. The one meaningful thing about it all was, in '68 this was more or less the end of the cold war. Even in the Bond movies they gave up the KGB as the enemy and turned to self-employed villains. So in '67, one had the feeling that the cold war was over, Russia was changing. But also our world was changing with new values, with a new vision of the world in which the Beatles played an important part. So the Meanies, in a way to me, represented a symbolic version of the cold war. And originally they were the Red Meanies. But the assistant who came in to do the coloring either did not quite understand my instructions, or deliberately did not understand them, but it also could be we didn't have enough red paint in the place. So they became the Blue Meanies.

I followed another good artistic advice knocking out these things. I knew that part of my subconscious would go into these things. But I chose to disregard that, I simply did not want to know what's happening. I mean, otherwise, I couldn't have done the work. I simply chose not to know what subconscious influences and things went into the work. And in a way, after this outline was later fleshed out by other people, like Erich Segal, this became a reservoir of the collective unconscious at the point of the flower power revolution.

The location of the Yellow Submarine has always puzzled me. Because many times when I saw the movie in the theater the Yellow Submarine is located atop of what I had thought looked like a Mayan type of pyramid. And of course, on closer scrutiny, it turns out to be a bandstand. Which could be interpreted still along the same lines as a Mayan pyramid. Did you give that any thought to that possibility?

Edelmann: You know, the production was one of the most chaotic in the entire history of film. And the sequence of work was not as in live action movies. Also, this was not starting on scene 1 and working all the way through the film. We did start off with a test, which was later included in the film at the very end. This tiny piece with George Harrison. This was a preliminary test and then we started improvising the travel sequence. The script was written and the outline was fleshed out as we went along. So the film, at least twenty minutes of the film, were finished in rough form, before we knew what the plot was going to be exactly.

And revisions were still made right up to the end with some part of the original Sgt. Pepper's Land, which came in very late in the movie. Which in my mind does not sit very well with the rest of the story. The trip to Pepperland was more or less improvised on the basis of the characters, also, the sea of monsters. And Charlie Jenkins' contribution made the Liverpool scene and the psychedelic scene right at the end.

The 'Lucy In the Sky with Diamonds sequence 'was done in quite another technique—painted directly onto cell traced off from live action.'—Heinz Edelmann, Website DesignGeorge Dunning, the main director, his contribution was the "Lucy in the Sky" sequence, which was done in quite another technique. Painted directly onto cell traced off from live action, and a sort of pure plot part with the Meanies at the beginning and the big battle scenes at the end. These were all done as the last thing, more or less, in the film.

Even at the end, when the production was closed down and people working on the film went off, it was discovered that the film did not have a proper ending. So the psychedelic end sequence was put together by the four of us using existing artwork over a weekend. I mean it, that's the way it is. One would have consciously liked to be part of a great masterpiece, but in a way, as the old pilots used to say, this was one I walked away from.

I know you've seen the Yellow Submarine paperback, the Signet paperback, which one time was 95 cents, and now you're lucky if you can find it for, well, in poor condition you'll pay 10 to 15 dollars, in good condition you'll pay 60 to 70 dollars.

Edelmann: Which, by the way, I did not do, and this was done on the basis of material cut from the production. You may have noticed that the paperback does not quite follow the story line of the film. And this was because it went into production before the script of the film was finalized.

'When I?m 64,' The Beatles, from Yellow SubmarineWhen we talked to Bob Balser and John Coates, they said that nearly 200 artists of all kinds were involved in this project. That's an astounding figure.

Edelmann: But these were animators and tracers and painters, and motion cell painters. I did all the characters and the basic look for each sequence. And maybe 25 of the Pepper people and those gray people in the background. Then somebody else came in and did the other two hundred. But the actual number involved in this was, the main background artists was two assistants, who then expanded my key sketches to the full background. And somebody who did the other characters as well. I think there may have been seven or eight people involved in the actual designing and inventing. The rest were animators, tracers and paint artists.

How did you direct the artists? You said you did the master drawings and they looked at them. Did you talk to them about what you thought it should be or what?

Edelmann: Just like the school master that I basically am, I watched over the whole thing. I did sneak around at night and check up on the work of the animators and leave rude notes if they lost the original design.

The Beatles, 'All You Need Is Love,' from Yellow SubmarineDid that happen often?

Edelmann: Well, it could happen because these were people who were brought in. We started with about twenty and over two hundred were there at the end of the production. We were behind schedule and being rushed all the time. I was there around the clock. I did get about four hours of sleep every second night. It took me years to recover.

During the production of the film did you ever meet or talk with the Beatles to get their feedback?

Edelmann: Yes, we did. As much as there wasn't much chance because it should be remembered at that time the Maharishi thing began and they were in India most of early '68 and only came back when the film was close to completion. Before that the Beatles were involved in their own Magical Mystery Tour. And of course, I did get to meet them. I was invited to the cutting room while they were actually cutting the Magical Mystery Tour.

Did they give you any feedback on the film itself?

Edelmann: Not really. We had a few discussions at early stages, because as I said, they went off to do their own Magical Mystery Tour and after that to India. So they were not really in London for most of the production.

There is one memory I treasure. Soho is now completely different, as the home of the advertising and film industry, but at that time it was a bit run down. Most of the cutting rooms were in Soho, but they were only along some streets, and there were only strip clubs. One of the animation directors and me went to see the Beatles, we were invited to join them at the cutting room. Afterwards we had lunch together. When we parted, there was nobody else on the street, just what you would call the people at the entrances of the strip clubs, the barkers or whatever. And we went one way, the Beatles went the other.

Everybody was waving, and then there was a strange, about 70-year-old gentleman who had roses behind his ears and a water tap glued to his forehead. And he was dancing in the crossroads. And we waved, the Beatles waved and all the people from the strip clubs waved.

'Once upon a time, or maybe twice, there was an unearthly paradise called Pepperland'

Pepperland and The Attack Of the Meanies, Yellow SubmarineAnd the end of the movie, you have the Blue Meanies putting roses in their...

Edelmann: That could have been inspired by the incident I just described. I mean this old man was a well-known eccentric around Soho, who somehow hung around the Beatles. He didn't just happen to be there. He knew that the Beatles were around.

There's been some research in the past 20 years that supports the theory that color can affect consciousness. The colors within the Yellow Submarine production are just exhilarating, they're uplifting. Was there any conscious choice in the palette to reflect this philosophy?

Edelmann: Well, more or less, of course, this is the American influence. These were Dr. Martin's dyes, which at that time were not available in England. I had to bring them in by suitcase from Germany. They just had been introduced. They were very strong, liquid water colors. I suppose they still exist, but highly concentrated. And they were later on used for the psychedelic slides people used to do by putting Dr. Martin's between two sheets of glass with some water.

'Hey Bulldog,' The Beatles, Yellow Submarine (excised from the final edit)

'It?s All Too Much,' Ringo, Jeremy, Blue Meanies, Apple Bonkers, Flying Blue Glove, Max and a great song—this scene has it all.But it's those colors that kind titillated one's emotional internal being to such an extent that it's almost like a drug, in a way.

Edelmann: Yes, well, this was to some extent done consciously. Because for one thing, the way the production went, I knew the story line would not stand up to close scrutiny. And also the animation was not quite what it might have been throughout the film. So to create some interest I did try to consciously overload the audience with impressions. The color, at least in the central part of the film, was just always a bit more than one would expect. And a bit more design than one normally expects to go with the story line. So, in the parts I could control through the design, I always try to slip in twenty percent more of what one normally in viewing a movie, would pick up. This was calculated to create this sort of constant overloading. I had never taken any drugs. I'm a conservative working class person who sticks to booze all his life. So I knew about the psychedelic experience only from hearsay. And I guessed what it was.

Now, during approximately the same time period of 1967-1968 you were completing a masterpiece that you will be forever connected with. There's a good chance that you have gone beyond your achievements of 25 years ago, and yet the world's critics may not give your later work the kind of attention it merits. How do you feel about that?

Edelmann: I do feel a bit like the ancient mariner with the albatross hanging around my neck. To give you an example, there is at the moment a show at a German museum, a show of my poster work which I've done after Submarine that I think of as my own personal work. And this show's going to be traveled; this was just the dress rehearsal, but at the opening there was some press, radio, TV and all they asked about was Submarine. And did I get to meet the Beatles? I'm not bitter about it and I've had my share of recognition afterwards, but sometimes I think they should have stuffed me at that time and displayed me in a museum.

But, this happened. And of course, who likes to think that he did the best work in his life at 33 and the rest was just a long slide downhill? But I think the most important job is the one coming up, and nothing else counts.

The Beatles, 'All Together Now,' final scene from Yellow Submarine

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024