Nineteen sixty-nine may have been the summer of peace and good vibes in some quarters, but down south, Elvis was exploring the seamy underbelly of intimate personal relations, when nothing goes right and the damage is deep and lasting. Had we been noticing, had we put it together since, we would have learned that it was the ol' Hillbilly Cat who stepped up, in June and again in November of that year, to apprise all who cared to listen that the party was almost over.

Taking Care of Business, Circa '69

How does Elvis fit in with Woodstock, Altamont, the Manson murders and the general tenor of the times at the end of the '60s? Herewith, the King's dark vision revealed...

By David McGee

FROM ELVIS IN MEMPHIS: LEGACY EDITION

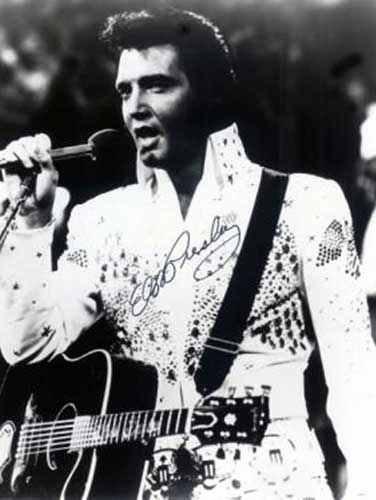

Elvis Presley

RCA/Legacy

In the accepted cultural history of 1969 the Manson Family murders, Woodstock, and Altamont are linked as symbolic of the apex and nadir of the peace and love ethos carried over from 1967's Summer of Love. Woodstock would seem to be the odd event out in that triumvirate, but in fact it was the second of three significant festivals of rock 'n' roll, blues and soul music that summer. Over July 4th weekend, the Atlanta International Pop Festival, poorly organized though it was (the Allman Brothers were booked by a phony promoter, and when they showed up were not allowed to play; Chuck Berry was billed, but never arrived), preceded Woodstock by almost a month and a half and featured several of the same bands; Woodstock famously unfolded between August 15-18; and over Labor Day weekend came the Texas International Pop Festival, again with many of the same bands that played Woodstock (a notable exception being Led Zeppelin, which was in Atlanta and in Texas, but not at Woodstock). All of these events were models of civility, if you will, with minimal scuffles, despite logistical hassles (lines of up to an hour for a soda, for example; traffic jams you don't wanna know about), and powrful displays of extraordinary music. Between Atlanta and Woodstock came the Manson Family murders, in early August; near year's end, December 6, came the Rolling Stones' ill-fated concert at the Altamont Speedway, with its increasingly escalating violence between beer drinking Hells Angels hired to guard the stage and unruly concert goers jacked up on LSD and amphetamines, a smoldering, toxic brew of paranoia, anxiety and anger that exploded, finally, in the stabbing death, by a Hell's Angel, of a gun-toting, methamphetamined Meredith Hunter. Even then it was easy to see the souring of the decade's good intentions and utopian visions, as if the slayings of JFK, RFK and Martin Luther King, Jr. hadn't already done so. In less than six months at the end of the decade, however, all the good and evil of the '60s conspired to make one last run at infamy.

Elvis Presley would not seem to fit into this story at all. Even though he had made some good records in the '60s, and had staged an exhilarating comeback at the end of '68, prior to that—from the Beatles' arrival until that moment on December 3, 1968, when his chiseled features filled the TV screen and he fixed the viewer with a steady, determined glare and spat, "If you're lookin' for trouble/you came to the right place..."—he had been pretty much a cultural afterthought, this putative King of Rock 'n' Roll who had never anointed himself as such nor contractually required anyone to refer to his regency when announcing him, as did a recently deceased self-branded King.

The comeback special demonstrated Elvis's reclamation of his artistry in bold, aggressive terms (and fashion—the leather suit he wore was symbolic of the badass artist who had paved the path for all who had come in his wake, then been left behind to watch as others took what he had built and ran off with it) and wiped away the unfortunate spectacle of years of inconsequential recordings and sophomoric films. The live "in the round" segments, in which he was accompanied by Scotty Moore on guitar and D.J. Fontana on percussion, the musicians who had been with him at the beginning, at Sun Records, and during which he not only sang as if his life depended on it, but played an absolutely fierce rhythm guitar (listen to him tear it up on "Tiger Man," if nothing else; it's scary), in the closest moment to an improvisational setting as we were ever allowed privy to as fans, was proof enough that he had returned to being the Titan his faithful followers knew him to be. The comeback special allowed him to explore all the myriad roots of his musical identity—country, gospel, blues, pop, and downright filthy rock 'n' roll—and he attacked his mission with a zeal that leaped off the screen and reignited the passions of critics and fans alike. Elvis always had been the real deal, but even he seemed to have forgotten that immutable fact somewhere along the way.

Elvis Presley, 'Suspicious Minds,' a bonus track from the Back In Memphis sessions, 1969; an outstanding live performance here, filmed in 1970.Some astonishing tours of the States would ensue from that December night, but even more remarkable (if anything can be said to be more remarkable than Elvis at his best on stage) was what happened in the recording studio immediately thereafter. Nineteen sixty-nine may have been the summer of peace and good vibes in some quarters, but down south, Elvis was exploring the seamy underbelly of intimate personal relations, when nothing goes right and the damage is deep and lasting. Had we been noticing, had we put it together since, we would have learned that it was the ol' Hillbilly Cat who stepped up, in June and again in November of that year, to apprise all who cared to listen that the party was almost over. This assertion came in the form of two albums, first, From Elvis in Memphis, released in June; then the second of a two-album set comprised of a live recording (From Memphis to Vegas) taped in Las Vegas, the second, titled From Vegas to Memphis (reissued as a single disc a year later titled Back In Memphis), of cuts from the same sessions that produced the June release. Some of the best of his many incredible singles sprang from this batch of recordings: the disturbing social commentary of "In the Ghetto," the abject loneliness depicted in Eddie Rabbit's "Kentucky Rain," the wrenching portrait of a boy trying to comfort a distraught father grieving for his deceased wife in "Don't Cry Daddy," and of course the searing, conflicted emotions driving the specter of betrayal Elvis recounts so witheringly in "Suspicious Minds."

When it came out, From Elvis in Memphis was greeted with unanimous critical acclaim as one of his best albums ever, and more than 30 years later, in 2003, it ranked #190 on Rolling Stone's 500 Greatest Albums list. From Vegas to Memphis aka Back in Memphis did not enjoy similar critical acclaim, but it did strike a nerve with fans, peaking at #12 on the pop chart. Both albums now are repackaged with original artwork and new liner notes, courtesy the good folks at RCA/Legacy, and lo and behold, if the King doesn't seem positively visionary in offering a dyspeptic view of the proceedings. In this Woodstock summer, in this summer of the moon walk's 40th anniversary, in this summer when we've lost Walter Cronkite, a man who spoke truth to power unceasingly throughout his career—never more dramatically than during his 14-minute, post-Tet Offensive examination of the Vietnam War effort in which he concluded that America could do no better than a stalemate with the enemy in those southeast Asian jungles and for all intents drove Lyndon Johnson from office—in this year of the lesser acknowledged anniversaries of events we might rather consign to history's dustbin, Elvis returns with his message from 1969, to wit, it's a mean old world out there, better take care of your heart because others won't.

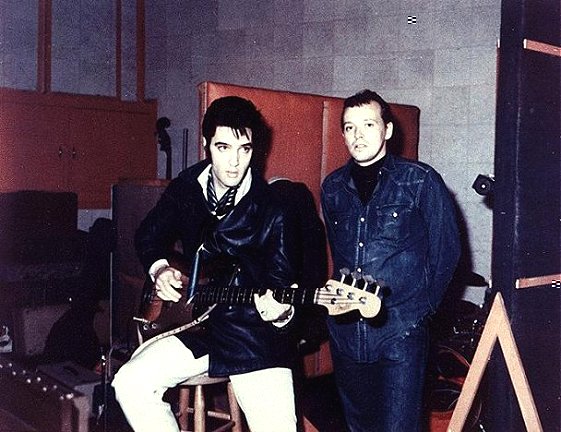

There are a couple of storylines here. One is the pure musical facts of the endeavor, now well known to Elvis fans and to most knowledgeable fans of pop music history in the late 20th Century. The sessions took place in January and February 1969, 13 years after Elvis had last recorded in his home town. In the meantime, legendary producer/songwriter and all-around colorful character Chips Moman had broken the Sun/Stax studio hegemony in Memphis at his own American Sound Studios, which would chart 122 hits between November 1967 and January 1971 (including the unbelievable but true stat of placing 28 records on Billboard's charts in one week). In the same way that Sun, Stax and the competing FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound studios in Alabama did, American was bolstered by a house band populated by incredible musicians on the order of Dan Penn, Reggie Young, Bobby Wood, Bobby Emmons, Tommy Cogbill, Gene Chrisman, Mike Leech, and various background vocalists, black and white, all summoned by Moman according to each session's needs (for Elvis he even recruited his protégé Sandy Posey, with whom he had created one of the earliest and finest songs relating to the budding feminist movement, "Born a Woman," a #12 single in 1966). In the second volume of his essential two-volume Elvis biography, Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley, author Peter Guralnick described the link between musicians and producer thusly: "These musicians [Moman] bound to him with an unquestioning loyalty, some might say with all the mesmerizing influence of Colonel Parker himself. That was how American, which had assumed its present shape not as a label but as a studio-for-hire in 1965 and had been turning out hits ever since, had achieved such cachet. Recording at American had turned out to be something of a talisman of good luck for artists as diverse as Wilson Pickett, Dusty Springfield, Dionne Warwick, and the Box Tops. Which was how everyone around Elvis who had pushed for his selection of the studio hoped it was going to work out for him."

'Don't Cry Daddy' and 'In the Ghetto,' both written by Mac Davis, Elvis live in Las Vegas, 12 August 1970Then there are the songs, chosen for the sessions by Moman, from songwriters he trusted to deliver a bit more depth than Elvis had been used to in recording movie soundtrack after movie soundtrack through most of the '60s, each seemingly more mundane than the one preceding it. Moman was no fool, though, and though it's not chronicled anywhere, the savvy choice of material for the American sessions indicates not only his understanding of what Elvis could deliver when challenged, but his awareness of some of the exceptional work that had shown up on the soundtrack albums as bonus tracks, not included in the movies, recorded as singles and used to fill up the long playing disc. A surprising amount of it had gone largely unacknowledged, but it served notice of how Elvis's artistry could be sparked to life when he got hold of a song with either a dramatic emotional component or a clever lyric mated to a hot rhythmic concept. Moreover, when fully engaged, Elvis could sing anything and do so with an innate understanding of the idiom. He knew all the moves.

So, Moman (and others in Elvis's circle, such as Lamar Fike, and publisher Freddy Bienstock, to be fair) drew from new and old wells for material, allowing Elvis, in effect, to construct a mosaic of his varied influences—traditional country in Hank Snow's 1950 chart topper, "I'm Movin' On" and early country-pop balladry by way of Eddy Arnold's 1947 "I'll Hold You In My Heart (Till I Can Hold You In My Arms)"; some down-home philosophizing from a mother to her son in the Jerry Butler-Kenny Gamble-Leon Huff R&B smash, "Only the Strong Survive"; a rare, subtle dig at race relations from the pen of a man who was a master of the art, Percy Mayfield, in the percolating "Stranger In My Own Home Town"; contemporary country-pop by way of John Harford's "Gentle On My Mind," a huge hit and Grammy winner in 1968 by Glen Campbell but also a Grammy winner that same year for its composer, Hartford, whose own wry, laid-back version, after which Elvis modeled his, was honored with an award as Best Folk Performance; and from the pen of the virtually uknown young songwriter Mac Davis (whose lovely ballad "Memories" had been one of the highlights of Elvis's TV special and became a fan favorite in concert), an unvarnished bit of social commentary about the price a society pays for allowing racism and poverty to fester, "In the Ghetto," a more pointed and controversial commentary on the culture than Elvis had offered at the end of his comeback special, which he closed with a hopeful message of racial conciliation, "If I Can Dream."

Elvis and producer Chips Moman at American Sound Studios in Memphis, 1969: During the 23 takes that finally yielded up 'In the Ghetto,' Chips Moman, according to Elvis's biographer Peter Guralnick, was, 'throughout it all, nothing but gently understated and encouraging, playing the session, the session musicians, and the singer as if they were a single finely tuned instrument.'How Elvis got to the magnificence of these tracks is another story altogther. He arrived at American fighting off a cold and battling a bad case of jitters over being placed in unfamiliar surroundings with musicians he hadn't worked with before. There were many difficult routes taken to wind up with finished versions of the songs, and as the players noticed, Elvis's famous stamina and work ethic carried him through, impressively so. In recounting the session for "Wearin' That Loved On Look," a pulsating blues from Dallas Frazier and A.L. Owens, Guralnick noted that Elvis, despite his hoarseness and difficulty controlling his voice, '"gave it his all through fifteen arduous takes, sinking his teeth once again into the pure feeling of the song. By now the musicians had actually begun to sit up and take notice. Glen Spreen found that he was impressed despite himself, not so much with Elvis' technique as with his soulfulness, his ability to make a song live-it was almost like going to church. 'We didn't have a real vocal booth,' said Mike Leech, more an observer than a participant the first few nights, 'bu we had a baffle that the vocalist would stand behind, with a window in it. And he was back there just like he would be onstage, doing gyrations and the whole thing-because that was just the way he sang. He sang everything like that; he'd have his eyes shut and he was sweating pretty good at the end of each track—he just got into it.'"

Elvis, 'Kentucky Rain,' written by Eddie RabbittEven more revealing is the session for "In the Ghetto," a song Elvis initially resisted on the theory that a performer offering up a message song, dabbling even ever so slightly in hot button political topics, risked alienating his audience. After some back-and-forth debate, with Elvis's close friend George Klein at first objecting to Elvis doing the song, then later reversing himself, and Chips threatening to give the song to his new American artist, football star-turned-actor-turned singer Rosey Grier, Elvis agreed to cut it. The session lasted from nine p.m. one night into the early morning hours of the following day, and to hear Guralnick recount it is to believe something miraculous occurred, one of those moments when song, artist, musician, producer and history are so in sync it's nigh on to supernatural.

Guralnick: "If you have never heard of Elvis Presley but were simply presented with the twenty-three meticulous takes of the song that he did on that night, it would be virtually impossible not to be won over. The singing is of such unassuming, almost translucent eloquence, it is so quietly confident in its simplicity, so well supported by the kind of elegant, no-frills small-group backing that was the hallmark of the American style-it makes a statement almost impossible to deny. Later, horns and voices would be overdubbed to add a dramatic flourish, but you can hear a kind of tenderness in those early takes that most recalls the Elvis who first entered Sam Phillips' Sun studio, offering equal parts yearning and social compassion. To the musicians, this was clincher. 'He just sang great,' said trumpet player Wayne Jackson, an American regular who was observing the session in advance of doing overdubs. 'The first time I heard 'In the Ghetto,' I just really felt slimy all over. I thought, 'Oh, my God, this is wonderful. This is it!' As the song develops, subtle adjustments are made, with Elvis quick to acknowledge mistakes and eager to get on with it-and one is provided with an incomparable glimpse of what the process might have been like for Elvis, if only he had been able to approach recording consistently as an art. Throughout it all, Chips, ordinarily perceived as an abrasive man, is nothing but gently understated and encouraging, playing the session, the session musicians, and the singer as if they were a single finely tuned instrument."

These are the moments, by turns trying and transcendent, from which two remarkable albums emerged under Moman's steerage. Yet another part of the story is the final selection of songs comprising those albums, a tale writ large and in pentimento as well by the mood and subtext of the assembled tracks. For both From Elvis in Memphis and Back in Memphis, minus the bonus tracks included on this CD reissue, form a bleak portrait coalescing in expressions of despair, bitterness, resentment, class consciousness and self-recrimination. So it was that Elvis, between the beginning of the summer of '69 and the decade in ashes at year's end, offered a decidedly pessimistic take on the prevailing zeitgeist. By the force of his emotional entanglement with the material, he gives the songs a larger context, making of personal betrayal a comment on a culture that turned on itself, in the end. Both "Long Black Limousine" (From Elvis in Memphis) and "The Fair's Moving On" (Back in Memphis) are at once literal and metaphorical accounts of an affair's sad demise—the former specifically references a woman's death in a car wreck, but at the outset Elvis is practically sneering at her haughty, big city ways and friends in a display of class consciousness in which he had not often engaged in his career, and in the latter graphic descriptions of an actual fair packing up and leaving town morph into symbolic expressions of passion gone cold, completely burned out, both songs figuratively lobbing caustic appraisals at the inhabitants Woodstock Nation like so many hand grenades.

In time, then, these Elvis albums, which when new were such bracing examples of a great American artist returning to his peak form, are still towering, but they have also taken on a much darker hue. The engaging, casual banter with which he invests his terrific take on "Gentle On My Mind" is the rare light moment here, and not necessarily one that fits the overall concept, but then there wasn't an overall concept back then. Someone must have known, maybe Elvis, maybe Chips, what was afoot thematically when it came time to select the original dozen (From Elvis in Memphis) and original 10 tracks for release. From Elvis in Memphis begins with the howl of "Wearin' That Loved On Look," which, despite its whimsical "shoop shoop" fills in the first verse, is a merciless screed aimed at an unfaithful partner—"I had to leave town for a little while/You said you'd be good while I'm gone/But the look in your eye/Done told me you told a lie/I know there's been some carryin' on..." and wends it way through the savvy tip about self sufficiency courtesy Jerry Butler ("Only the Strong Survive") through the abject heartbreak of "It Keeps Right On A-Hurtin',' "After Loving You," and, from the same writers who crafted "Wearin' That Loved On Look" (Dallas Frazier and A.L. Owens), a curiously downbeat, bluesy love ballad, "True Love Travels On a Gravel Road" that demands a close listen to figure out the lyric is actually extolling the persistence of love through hard times, before winding up with the unsettling dramatics of "In the Ghetto." Back in Memphis opens with Eddie Rabbit's "Inherit the Wind," a story warning against loving a man with a genetic predisposition to wanderlust; "This Is The Story," one of two songs from the team of Arnold-Martin-Morrow, is pretty much summed up by the key lyric, "This is the story of a man whose world is falling apart/And it's the story that is breaking my heart," ahead of Moman laying on a keening gospel chorus to enhance the sentiment's impact; the same team is responsible for another heartbreaker, "A Little Bit of Green," which contrasts a bright, sprightly rhythm against winsome narrative about infidelity. Sandwiched between the latter two numbers is a nice slab of southern funk in the horn-rich fatback energizing Percy Mayfield's "Stranger In My Own Home Town," and Elvis sings it with a weary resignation, in a near-conversational style that makes the social ostracizing he experiences after coming home "with good intentions, about five or six years ago" (where he was is never revealed, but jail is a good possibility) seem like the matter-of-fact experience it was for people of color when Mayfield wrote the tune, and Elvis treats it with something approaching disdain and spite for those who won't give him a chance, until at the end he's pushing the band hard to a bustling fadeout. From Mort Shuman, who with his partner Doc Pomus contributed several classics to the Presley canon in the '60s, comes the penultimate track, a driving, bittersweet revenge scenario in which the singer exults in the idea of the girl who dumped him getting what's coming to her and longing for him instead. Back in Memphis closes with a gospel-ized reading of Clyde McPhatter's magnificent tearjerker from 1957, "Without Love (There Is Nothing)," complete with a churchy piano and a fervid gospel chorus soaring into the choruses behind Elvis, who himself is in full flight vocally, singing in a booming, hearty tenor as he proclaims what, oh, Count Dracula learned, to wit: "The absence of love is the most abject pain." (In its original incarnation Elvis in Memphis contained no gospel numbers, but this reissue includes as a bonus track, "Who Am I," a powerfully understated sacred performance that finds a penitent Elvis entirely submissive before a higher power as he ponders his own worth and the grace blessing his undeserving life.)

And there you have it. To the Peace & Love generation, Elvis submitted on the one hand an affirmation of its basic premise, but on the other, a travelogue through a world where those idealistic dreams, however admirable, are more often elusive than attainable. The bonus tracks add some extra meat on the bone, in bringing other non-album singles into the proper timeframe of their recording (note: these tracks, 14 in all, also include two of the most disastrous moments in Elvis's recording history, his stilted version of Lennon-McCartney's "Hey Jude," and a schizoid treatment of "I'll Be There," the Bobby Darin-penned song familiar mostly as a 1965 British Invasion hit for Gerry & the Pacemakers, who should be especially proud of their exemplary recording after hearing it butchered here), but the heart of the matter is the 22 songs offered to a self-immolating world in 1969.

In Bobby Russell's agonizing "Do You Know Who I Am?," on Back In Memphis, Elvis sings/asks, "Do you know who I am? Do you have any idea who I am?" The evidence suggests if we did, we didn't pay close enough attention; and if we didn't, there's still much to learn. So much to learn. This is humbling art.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024