'A National Treasure'

A Tribute to John Updike

By David McGee

John Updike (March 18, 1932-January 27, 2009): 'Our time's greatest man of letters'

Photocredit:AP Photo/Caleb JonesJohn Updike, poet-essayist-critic-novelist of protean artistry and limitless scope, died of lung cancer at a hospice in Danvers, MA, on Tuesday, January 27. He was 76. Although at times he ventured to other lands in his fictional excursions—his 1978 novel The Coup is set in an imaginary African nation; the action in 1997's Towards the End of Time takes place in the year 2020, following a war between the U.S. and China; and one of his late-life virtuoso performances, his underrated 2006 novel, Terrorist, is set in America, but told from the point of view of a young, recent convert to Islam bent on blowing up the Lincoln Tunnel, who is alienated, radicalized and marginalized by the shallow, profane popular culture in a land the author himself seems not to recognize anymore—he was indisputably and unequivocally middle class American on and off the page. Of his 60-some books, his tetralogy of Rabbit novels alone place him in the pantheon of this country's greatest 20th Century authors. The first, 1960's Rabbit Run, the work that shot him to mainstream fame following the literary success d'estime of his first novel, 1959's The Poorhouse Fair, was followed by Rabbit Redux (1971); Rabbit Is Rich (1981); and Rabbit At Rest (1991) (plus a touching postscript to the Rabbit story, Rabbit Remembered, a novella published in the short story collection Licks of Love in 2000), comprising an intimate chronicle of the life and times of Harry Rabbit Angstrom, a former high school basketball star perpetually seeking escape from the existential angst of his loveless marriage to Janice and a boring sales job, as the America of his Pennsylvania youth changes in ways that alternately confound, exhilarate and sadden him. ("He resisted growing up, and he resisted it to the very end," Updike himself said of his creation, Angstrom. "He didn't take advice very easily, which I think is typical of most Americans.") In his fiction Updike frequently returned to his native small town Pennsylvania—he was born in Reading on March 18, 1932, and raised in Shillington—creating the Shillington-like town of Olinger to stand in for his own home town, with Rabbit Angstrom his doppelganger, confronting and puzzling out unnerving personal and societal changes in the Brewer suburb of Mt. Judge. Updike preferred the comfort of the familiar geography and close-knit social fabric of the contained communities of Mt. Judge and Olinger; of familiar streets—Potter Avenue, Wilbur Street, Jackson Road, Kegerise Street—lit by dim lamps and defined by unassuming storefronts; and of lusted-after, unattainable girls—Lotty Bingaman, Margaret Schoelkopf. This external and internal geography inspired reflective, lyrical ruminations, in short stories such as "In Football Season" and in the Rabbit saga. Despite a near-sentimental affection for the small town, middle class life, he unflinchingly exposed what it hid: the hypocrisies, the betrayals, the infidelities, the political gamesmanship, and in Rabbit Angstrom he gave an accounting of his American era, publishing each novel in 10-year intervals, each installment set in and driven by the conflicts of the decade preceding its publication. What took him four novels in 40 years to do in the Rabbit books he accomplished in a single, masterful volume in 1996's In The Beauty Of the Lilies, in which he took the pulse of the spiritual, cultural and psychological tenor of the 20th Century as reflected in the shifting fortunes of the Wilmont clan. In this territory, he was right where he belonged: as he said in a 1966 interview with Life magazine, "My subject is the American Protestant small-town middle class. I like middles. It is in middles that extremes clash, where ambiguity restlessly rules."

Venturing away from the "middles" periodically, Updike produced whimsical, knowing light verse, and gems perhaps only he saw coming. Sports was an interest, but not his regular beat; yet in 1960, for The New Yorker, he produced a Hall of Fame-worthy piece on the final professional game of the Boston Red Sox's legendary Ted Williams, "Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu" (see excerpt in this issue), in which he captured not only the unfolding drama of the contest on the field but also one of baseball's indelible moments, in a poetically rendered, deliberately paced summation, in literary slow motion, of the Splendid Splinter's final at-bat, when he hit a home run off Bill Fisher. In contrast to today's boisterous, ill-mannered sports crowds, Updike's blue-collar Red Sox fans were portrayed as witnessing history with an odd mix of awe and resignation, observations he gleaned first hand by sitting in the stands, not in the press box. In 1999 he and artist-illustrator Edward Gorey produced a slight (24 pages) counter-celebration of the holiday season titled The Twelve Terrors of Christmas. On facing pages Gorey's macabre, shell shocked children and adults were captured in unsettling scenes (a blubbery Santa Claus stuck in a chimney, an elderly man watching in fright as shingles inexplicably fall off his roof) opposite Updike's succinct, explanatory, sardonic text: the fifth terror, titled "Tiny Reindeer," explains those falling shingles:

Hooves that cut through roof

shingles like linoleum knives.

Unstable flight patterns suggesting

To at least one observer "dry leaves

That before the wild hurricane fly."

Fur possibly laden with disease-

Bearing ticks.

News of Updike's death prompted an immediate outpouring of effusive, heartfelt appraisals. Two of the most informed, balanced pieces were published in the January 28 edition of The New York Times, with critic Christopher Lehmann-Haupt contributing a lengthy obituary and author Lorrie Moore offering a warm tribute in "The Complete Updike," on the Op-Ed page, in which she astutely summarized the author's oeuvre: "Mr. Updike's novels wove an explicit and teeming tapestry of male and female appetites. He noticed astutely, precisely, unnervingly. His stories, some of the best ever written by anyone, were jewels of existential comedy, domestic anguish and restraint."

In the Lehmann-Haupt obituary, author Philip Roth, an Updike peer, states: "John Updike is our time's greatest man of letters, as brilliant a literary critic and essayist as he was a novelist and short story writer. He is and always will be no less a national treasure than his 19th-century precursor, Nathaniel Hawthorne."

The one time I encountered Updike in the flesh, in his lecture appearance at New York's 92nd St. Y in 2005, it was not his urbanity, droll wit or intellectual rigor that made the greatest impression. At the time he was anticipating the publication of Still Looking: Essays On Art, a collection of essays he had published primarily in The New York Review of Books. Producing a portion of the manuscript, he shared an excerpt with the audience. As he read, he smiled, his soft, bemused voice taking on the wondrous tone of someone awestruck by the prose, but not in an egocentric manner. Rather, he read with a sense of childlike excitement at discovering the magic of words so elegantly crafted, as if not quite believing how a raw slab of the English language had been sculpted into a thing of beauty, a work of art itself. He seemed somehow apart from his own creation, experiencing its discovery for the first time, and exulting in it. A writer of some experience who hasn't looked back on his or her outpouring and cringed, at least a few times, is likely not to have grown, and Updike surely had his own checklist of rueful interludes amidst the breathtaking displays of style and substance in his life's calling. But for a moment we all saw him coming to his work exactly as we had been doing, lo these many years: open and eager to be surprised, startled, aroused, moved, challenged, inspired and enlightened. With apologies to Lennon-McCartney, he was we and we were he and we were all together. Updike knew how to speak to his own, summoning an uncommon gift to serve the purpose of understanding and illuminating the full complexities of common lives and making sense of the drift of time, in his own time, for better or for worse, evoking the world as it was, and is, in delicate balance in all dimensions.

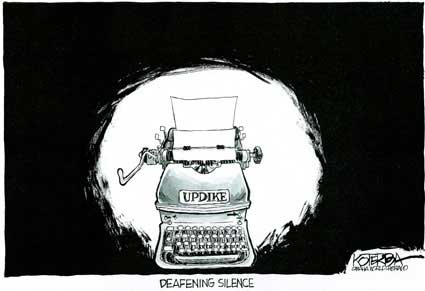

After thousands upon thousands of words of praise and wonder have been visited on John Updike and his art, the most perceptive analysis of all came by way of pen and ink—Updike may well have preferred it this way, too—in an editorial cartoon by Jeff Koterba of the Omaha World-Herald. After all the appraisals and hosannas, perhaps we can best measure, and feel, our country's loss in Koterba's pictorial evocation of the suddenly stilled voice:

Go here for excerpts from Updike's work...

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024