“Crazy Ivan”: Alison Brown at the Americana Folk Festival, November 2008, performing the opening track from her latest album, The Company We Keep, featuring a spectacular piano solo by her long-time musical collaborator, John R. BurrAlison Brown: In Good Company

TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview

Celebrating 15 years of her Compass label's history, a bluegrass adventurer maintains a healthy balance between executive duties and motherhood, and keeps on pickin' the banjo like nobody's business

By David McGee

In a time of near-unrelenting bad news from the business sector, herewith a report on a success story continuing unabated through hard times. This year Compass, the respected roots music label, marks its 15th anniversary. Its roster has expanded from traditional and progressive bluegrass to include a formidable lineup of Celtic, World Music, English folk, jazz, pop-rock-AC, folk, and fairly unclassifiable progressive fare such as Victor Wooten's solo album—more than 200 albums all told in the company's catalogue; even a couple of high-profile refugees from the '80s rock world: Colin Hay (formerly of Men at Work) and Glenn Tilbrook (one-half of the beloved Squeeze's songwriting team) have found Compass the ideal home for their latest solo projects.

More than an adventurous, often daring, enterprise, Compass is testimony to the vision of its founders, Grammy winning (for Best Country Instrumental in 2001, honoring "Leaving Cottondale" from her Fair Weather album) banjo virtuoso Alison Brown and Garry West (a Delbert McClinton band alum who, in addition to playing bass in Alison's ensemble also happens to be her husband and father to their two children). Their plan came together at a table in a Stockholm café, during a break while touring with Michelle Shocked, for whom Alison was serving as bandleader. Even at that early stage of her career Brown had some weight to throw around: she had broken into the business in her teens, touring the country with fiddler Stuart Duncan and his father, playing festivals and entering contests, finishing first at the Canadian National Banjo Championship, which led to an appearance on the Grand Ole Opry; after graduating from high school, she made her debut on record, cutting an album with Duncan, Pre-Sequel, released on the Ridge Runner label. Upon finishing college, entering and then leaving the business world, she worked for three years with Alison Krauss's band, a tenure that saw her recording her debut solo album, 1991's Simple Pleasures, for Vanguard, with a number of David Grisman band members and alumni assisting; lo and behold, it was nominated for a Grammy. Clearly, the comely blonde picker had come a long way since earning her MBA at UCLA (where she matriculated after receiving an undergrad degree in history and literature from Harvard) and walking away from life as an investment banker into the riskier business of chasing her musical dreams.

"I took a small leap of faith," she said in a bit of an understatement to The Improper Bostonian magazine in a May 3, 2005 feature. "I was underwriting tax-exempt bond issues, which is about as exciting as it sounds. I just decided, not that I'd never do it again, but I wanted some time off."

Her banker's holiday morphed into a new career. In 1991, her Grammy-nominated year, she became the first female ever to win the IBMA's Banjo Player Of the Year Award (and remained so until last year, when Kristin Benson, now the Grascals' new banjo player, nabbed the honor). Moreover, she has fashioned a stirring recorded legacy of 10 albums, four for Vanguard and six, including her newest, The Company You Keep, for her own label. (Not wanting Compass to be misconstrued as a vanity project, she didn't move her music to her own company until 1998 for the label’s 25th release.)

The Company You Keep is an all-instrumental effort (Brown does not sing, but in the past she has had guest vocalists on the order of Vince Gill and the Indigo Girls sit in on selected cuts) of scintillating moods and shifting textures, with all but two of the tracks either written or co-written by Brown. On the occasion of Compass's 15th anniversary, we checked in with the Connecticut-born, Southern California-raised artist, now 46, not to rehash her journey through academia and big business or for a routine retrospective of Compass's history, but rather to use the new album as a jumping off point for a sweeping discussion of her creative process as reflected in the new material, the guiding principles of her label stewardship and the issues she confronts in an industry undergoing seismic (and far from being settled) structural alterations affecting everything but the music itself. Artist-owned, artist-operated and artist friendly, Compass is in fact a hub of activity, and so it was that Brown took our call at her executive desk, where she spends untold hours pondering quaint and curious volumes of arcane business lore most of us would need an MBA to understand. When she's not at her desk, she may be touring or recording (or producing—she was behind the board for Dale Ann Bradley's forthcoming new album), or, equally likely, being mother to her two children by West, the youngest of whom recently celebrated birthday number two. Given this full house of responsibilities, she is surprisingly sanguine in conversation, answering questions and offering insights in a confident, calm, gentle voice emanating a rational, motherly serenity. There may be a hard-nosed businesswoman in there somewhere, one given to terse, clipped responses, but you can bet the farm she keeps her under wraps unless she's absolutely needed. In all matters, a balance, and she wouldn't have it any other way.

***

Alison on stage with husband/bassist Garry West and their two children, Brendan and budding songstress Hannah: ‘In the time I made the last record and we started The Company We Keep, we've had another child. And when we were recording Company he was not quite one year old. My hands were literally full—physically, literally full—so I hadn’t had time to sit down and write music the way I used to. Part of the idea with this record was to turn what could be a disadvantage into an advantage, and really draw out the contributions and voices of the other musicians.’Your album titles have never struck me as being whimsically chosen, but instead as having some meaning to something relevant to your life or the music inside. The Company You Keep, reflects an album in which the music explores moods and emotions, which is the company we keep as individuals. Is that what this title refers to?

Alison Brown: That's an interesting thought, and I had actually never thought it through to that depth. Actually, I was really just thinking about how the band has been together now for 16 years, and it's pretty much been the same personnel the whole time, particularly John R. (Burr, piano) and Garry (West, bass, and Alison's husband). And I was thinking about the music and the context of the three of us, and mostly the four of us, working together to develop this hybrid sound that we've honed hopefully into something good over the last 16 years, and hoping to draw attention to that, and to the importance of those particular people being there for the journey.

Then I started thinking about it in a broader sense; we really launched the band and the label at the same time, so the two things have grown up together. So it's a tip of the hat to the company as well.

You mentioned the hybrid sound. Do you feel it's more fully realized on this album than ever before? It does sound like there's something extra going on in terms of the musicians' communication with each other.

Brown: I think so. The whole approach to the music was completely different this time. On previous records I've come to the project with material basically written, and it's been the process in the studio to come up with the arrangement and maybe add a section or two, but mostly just arrange the tune, put it down. In the time I made the last record and we started this one, we've had another child. And when we were recording Company he was not quite one year old. My hands were literally full—physically, literally full—so I hadn’t had time to sit down and write music the way I used to. Part of the idea with this record was to turn what could be a disadvantage into an advantage, and really draw out the contributions and voices of the other musicians by, in most cases, co-writing the material either in the studio or the night before we recorded it. If you're hearing that the music's gone to a different place, it makes me really happy because I hoped that the outcome of writing and recording the music that way would lift the music up to this new place, because I would be inviting more participation from the guys who had been working on this with me for 16 years and could bring so much to the table in the creative process.

You went in the studio with the framework for each song and then worked with the band to develop it from there?

Brown: Not even that.

A lick? A riff?

Brown: Yeah, you know, in some cases, maybe a section or maybe a lick, or maybe an idea for a title. We've been doing this together for so long that it's not as daunting as it sounds. It sounds like, Oh my God, you could really fall on your face! But we have this great structure for doing that now that we didn't have before, because we have a studio. It's just upstairs from our office, and the engineer in the studio is also our live engineer and knows our music inside and out. So we can go into the studio with our band and there's a great comfort level there that allows you to do what otherwise might seem, if not impossible, certainly ridiculous. Because we did it that way it gave us freedom to do something a little bit different. It's a challenge when you're an artist on your tenth record to answer the question, Why does the world need another record from you? What can you do to make a consumer need to have that record? That's a real challenge that I think about a lot because I'm on the business side of the record too. So, hopefully, it did give it a bit of a different spin, But yeah, for instance the opening track, "Crazy Ivan," the intro for that tune started off as a banjo riff, and that's really all we had. In that case, we took the meter that the intro set up and John R. (Burr, piano) and (guitarist) John Doyle were playing the groove, and I came up with the melody. There was a feeling that it needed to go to this brighter place where the sun comes through, so we came up with the B changes and that melody, then back to the A, and we knew we needed a C section. I had always felt tunewriting was equal parts inspiration and craft, and I feel now it's maybe more craft than inspiration; or certainly you can write a tune in the absence of the "God cloud" inspiration.

Was this album, then, a product of improvisational sessions in the studio until a form and structure for each number came together?

Brown: No, not really, we took more of a craftsman approach to it. We've got this A section, sort of an idea for a B. The way it really ended up was that John R. and I sort of spearheaded the writing and certain other people sat on their computers and worked on label business or answered email. He and I were really the biggest creative push behind it, then with John Doyle weighing in because he's so great with harmonic and rhythmic ideas on the guitar. And much of the material we wrote the night before the session at home, just me and John R. sitting at the piano with the banjo.

One of my favorite numbers on the album is "The Road West." I particularly like that because the interplay between the instruments is so captivating, has such great energy in the give-and-take, especially between you and the piano. John R.'s piano playing strikes me as a Bill Evans-ish motif that you're responding to, and then the mandolin comes in-the way you all interact and "talk" to each other in the song is exhilarating.

Brown: I appreciate you listening to it with that level of attention because sometimes you feel like with instrumental music it becomes sort of the background for whatever's going on. That tune is one of the tunes we didn't write on the record. It was written by an Irish accordion player, Mairtin O’Conner, who gave us a copy of his record when we played at a festival in Galway a few summers ago. It was the title track. If you listen to his version of it, the whole recording is in B flat because he plays, I guess, B flat piano accordion. So the first challenge was to move it into the key of G so it would lay well on the banjo; the second challenge was, We haven't done many covers, so what's the point of us doing it? How can we put our own spin on it? I was really happy with the way we figured out how to modulate after each solo. It made some kind of sense that way, and created a framework in which we sound like us.

It gives the song a lift each time you do that.

Brown: Yeah, it makes the song more interesting. There wasn't a lot of instrumental interplay on the original; it was just Mairtin O'Connor playing the accordion all the way through. It's nice to hear someone felt we added something.

‘It's a challenge when you're an artist on your tenth record to answer the question, Why does the world need another record from you? What can you do to make a consumer need to have that record? That's a real challenge that I think about a lot because I'm on the business side of the record too.’Obviously on any record sequencing is so important, and I thought the sequencing of this one, with "Waltz for Mr. B" at the end, was an inspired stroke, not only because it's a calm number but it has a cinematic quality about its arrangement—it seems bigger than it is and has that "summing up" feel about it.

Brown: I was proud of the way that tune unfolded. I have a tendency to end records with some kind of quiet tune like that. And my dad says, "Well, you did it again."

Your style has not been to dazzle people with banjo pyrotechnics; you complement the other instruments and remain part of the band ensemble.

Brown: That's the approach that feels right to me. I feel like it's as much a reflection of a female perspective as much as anything else. I've been in a number of situations where I was the only girl in the band, and in a couple of situations where it was an all-girl band. Men and women approach ensemble playing differently. When you play with a bunch of guys, it seems as if the goal is to claim your sonic real estate. When you play with a bunch of girls, women are supposed to be consensus builders and I really think that's true—"Oh, well, take my solo; I don't need one."—and our band is a completely different approach, but it's my world view. I've never wanted to be a person out front with a bunch of guys backing me up. I've been more interested in building an ensemble sound that weaves my voice into a tapestry that includes every other musician's voice in equal quantity. That's the way I want to hear music and the way it feels comfortable to me to present it.

With this group you've worked with so long, the level of communication between all the musicians must be innate by now.

Brown: Boy, you know we've been doing shows together since 1993, so there's an incredible level of trust and shared experience, and a sense that you can make it through anything, and if you want to try something, you know the other guys are there for you. All those good things that come from playing together, which I really enjoy. I like the idea of building something over a long period of time with the same group of people, and it's occasionally frustrating to me that the market wants artists to reinvent themselves on every record. That's not what feels right to me; Flatt and Scruggs didn’t do that; and the Modern Jazz Quartet didn’t either. What feels right to me is to develop something over a long enough period of time that you can see the arc of evolution.

‘Our dream is to be the last label an artist ever needs. I really like the idea of nurturing and developing a long-term relationship and helping an artist develop an artistic vision over a long period of time. We try to make that possible wherever we can.’Does that philosophy carry over to the Compass label? I know people come and go, but basically is that the aim?

Brown: Yeah, people come and go, but our dream is to be the last label an artist ever needs. So, yes, I really like the idea of nurturing and developing a long-term relationship and helping an artist develop an artistic vision over a long period of time. And we try to make that possible wherever we can.

If I can take you back to that pivotal discussion you had with Garry all those years ago about forming Compass, was there a model then for what you wanted to do? Or did you do it because in fact there wasn't a model for this kind of label?

Brown: There was a model. When we started our label—and it may be silly—but we were looking at Rykodisc, Vanguard Records, Red House Records, Rounder Records, Sugar Hill, and maybe even Acoustic Disc, as the models for what we wanted to do and to not do. So there was kind of a standard model for a record company, but I felt what was different with Compass was that it would actually be run, from a day to day standpoint, by musicians, for musicians. Obviously, there's Acoustic Disc, David Grisman's label, but he doesn't do the administration, royalty accounting, business affairs, promotion, developing marketing plans. So the model was similar to many, but the perspective was different.

I saw an interesting comment from you in reference to your thoughts about the Compass approach when you were forming the label. In short, you mentioned how Windham Hill would release albums of beautiful music by George Winston but the album cover would be a photo of a tree.

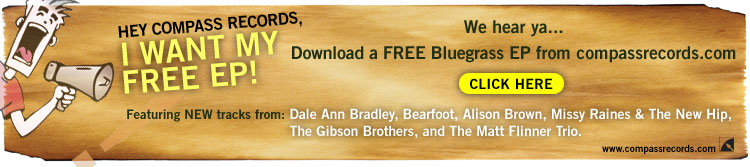

Brown: Right. When we started the label we got the Harvard Business School case study on Windham Hill and read it, and read it a lot. I'd been living in the Bay Area before moving to Nashville and I knew a lot of the artists, like Mike Marshall and Darroll Anger, Phil Aaberg, a lot of people who were on Windham Hill. So their model always fascinated me. I think I tried to get a job there once, too. But one thing that's really interesting about their approach—and on some level I'm a little bit envious of it—but they were all about building brand identity, and they did that by not building artist identity. Our approach has always been to put the artist on the cover and build the artist's identity. But when you look at Windham Hill, or today, Putumayo, it's hard not to feel a little envious because they’ve built such great brand identity. I don't know how you can do the two things simultaneously, but to some extent that's what we've wanted to do, to have people subscribe to our aesthetic as a company, and say, "Well, if I enjoyed a Celtic record on that label, maybe those same aesthetics would help me enjoy a bluegrass record on that label." We get orders on our website constantly and they're always coming to my Blackberry, so I can look at them 24 hours a day if I want to. It's always interesting to see someone buy a Colin Hay record and a Matt Flinner Trio record.

Your academic career is well documented. I wonder in looking back over these years, has your MBA been more important than your studies of literature and history, or vice versa, in terms of running the company?

Brown: The thing about most higher education is there's what you learn and there are also the people you meet while you’re learning. The people I've met, while at Harvard and as a result of having gone there, have been just great contacts for me. Those things have really helped. Studying history and literature is something that's always been and still is interesting to me, and I still read books in those areas, but it probably hasn't had a direct impact on the business as much as the direct network of people the university puts you in contact with. The MBA probably has a little bit more direct application to what we're doing, but just a little bit. I was too young to go to business school, so I didn't get as much out of it as I should have. If I went back now I'd get way more out of it. The time I spent in investment banking, I was doing really specific technical stuff, and I was able to pull general concepts out of that. I'm not afraid of a spreadsheet, but luckily I haven't had to refund a municipal bond in twenty years. That makes me very happy.

‘When we started our label we were looking at Rykodisc, Vanguard Records, Red House Records, Rounder Records, Sugar Hill, and maybe even Acoustic Disc, as the models for what we wanted to do and to not do. So there was kind of a standard model for a record company, but I felt what was different with Compass was that it would actually be run, from a day to day standpoint, by musicians, for musicians.’And what is your day-to-day involvement in the nuts and bolts of the business side? It sounds like you're very hands on in that regard.

Brown: Yeah, I'm sitting at my desk unless we're out on the road. I basically oversee all the financial stuff as well as royalty administration, weigh in on marketing plans, I'm always talking to the publicity team, looking at how records are performing and figuring out ways to help them do better, and producing records occasionally. I just produced Dale Ann Bradley's new record. She is so happy with this record, and that makes me happy. She's just awesome. I function in that capacity too, occasionally, where I'm up in the studio involved in the music side of things, so I really couldn't be more involved day to day.

When you started evolving the label, after Compass was founded and established, was there a plan to develop it as we know it now, especially with the Irish artists you've signed?

Brown: No, not at all. I bet when we started the label I thought of Irish music as a couple of guys in a pub in fisherman's sweaters singing "The Unicorn Song." Maybe not that quite uninformed, but pretty close. That really grew out of our touring and having opportunities to play in the Isles, especially the Celtic Connections festival in Glasgow, which is a thre-week long festival in Scotland every January. The organizer of that festival was really supportive of our band, and had us year after year over about a ten-year period. We'd go over there and meet all these other musicians from that side of the pond, and other opportunities to tour there would come out of it. That's really how the Celtic bent started—someone would be sitting around in the pub and someone would say, "You know, I'd really like to get a record out in the States and such-and-such a label doesn't have the best reputation," and we'd say, "Come to us, we'd love to work with you," and we started to build this roster of Irish, Scottish and English artists. Then when the opportunity came up to acquire the Green Linnet catalogue, it made sense for us. But that wasn't something we anticipated. We expected to be a roots music label but we didn't imagine Celtic music to necessarily be a part of that; I think we were thinking more of American roots music than world roots music.

So how does an artist like Colin Hay fit into the Compass profile?

Brown: Colin fits first of all as a person; if we didn’t feel a personal connection with him the deal probably would have never happened. He’d had an independent label of his own, but as a result of trying to sell his own music through that label label he’d grown tired of thinking too much about the business side of things and not enough about the music. He came to us, he had the right perspective and he was really interested in having a team he could work with to build his solo career up to a more meaningful place. From a musical point of view his is the most pop-oriented music we have, but it has an acoustic angle too and appeals to an adult demographic. So looking at it from a marketing point of view, it's a fit. Maybe he’s on the more commercial side of what we do, but there are many other artists in that realm, such as the Waybacks to a certain extent, and Glenn Tilbrook, whom we did a record with, and Victor Wooten, that it kind of fits sonically in that realm. Mainly, he's just a great partner, and in times that are as challenging as these for the industry the partnership aspect is really, really important.

With regard to the challenging times you mentioned, how about surviving this economic crisis? What have you had to do to adjust to that as well as to the transition to digital delivery?

Brown: Watch budgets, timelines for recordings; make sure every release has the things going on around it that warrant a national release, such as touring, noteworthy music, all those elements. I don't know that anyone knows how it's going to shake out. Is retail going to fade away or bounce back a little bit? First quarter this year has been really rough with retail; lots of big stores closing and reduction in shelf space. But it seems like it's getting a little bit better with the coming of spring, so maybe things will ease up. The one thing I firmly believe is that consumers still want to buy music and I'm really grateful that we can go out and play shows, sell CDs at the end of the night and put music in the hands of people and see how excited they are about it. So I know the consumers haven't gone away; they still want to buy music. The challenge is the method of delivery. How are we going to get music to people when retail doesn’t want to support it? Is it going to be physical, digital, direct to the consumer? Are we going to go through gatekeepers like Barnes & Noble and Borders or are they going to go away? How's it all going to happen? I don't know the answers to those questions, but we've been working very hard at building up our direct-to-consumer relationship. We’ve got a fifty-thousand-plus name database; we do monthly newsletters and we do sales and promotions, and we try to be in as constant contact as we can with our customer base without over-saturating them with stuff. I think that's part of the solution—if you can't count on retail beyond a certain level you just have to get the product to the fan directly, and luckily with a website we can do that.

It has to be some combination of that with roots music because so many artists count on those post-concert CD sales, and that means a physical product.

Brown: That's the other side of it—the venue is the new retailer in many markets so the physical product has to be there. Garry always points out that you can't sign a download. It's true, people like having the physical reminder of the concert and making a connection with the artist. They like having the artist sign a CD that they can take away. So we believe the physical CD, at least in this end of the business, will be here for a long time. I think people who buy bluegrass and roots music are buying it because it's a lifestyle product for them, whereas I think to people who buy most major label product it's more like fashion—here today, tomorrow they're going to be on to whatever the next thing is. The two consumer groups have different mindsets about that. If you buy Irish music, you have to have the package so you know what the four tunes in each set were, who wrote them, who played on them. I think people like to have that item on display in their house that connects them to a community that's important to them. It's a different mindset compared to the pop consumer.

‘When I figured out I could write my own tunes, and realized they weren't rehashed Earl Scruggs tunes, but had melodies that went into different places beyond bluegrass or through bluegrass to some other place—that's when the banjo started to become my voice.’You picked up the banjo at a young age, and it was Earl Scruggs who was the initial inspiration. Can you pinpoint a time when you felt like the banjo had really become your expressive voice? That is was really telling listeners who you are?

Brown: It’s an ongoing process, and I think so highly of instrumentalists who seem so fluent on their instruments. For me, that's my life's work. But I think it started to show when I began writing my own tunes. First of all, when I figured out I could write my own tunes, and realized they weren't rehashed Earl Scruggs tunes, but had melodies that went into different places beyond bluegrass or through bluegrass to some other place—that's when the banjo started to become my voice. I don't know if that's true for all instrumentalists, because there are instrumentalists who aren't composers who still have a distinctive voice. But I think composition is where I’ve felt I could make a contribution to the instrument.

What attracted to you to the banjo in the first place? What was it about the banjo that made you want to play it, stick with it, develop it?

Brown: We were growing up in Stamford, Connecticut—we didn't move to California until I was 12 or 13—and my parents had got into folk music because of the folk revival and they were taking guitar lessons. But there was no bluegrass in our house. My guitar teacher was a law student, of course, and he brought over an Earl Scruggs album, and that's how I fell I love with the five-string banjo; it was really the sound. How can you explain those things? It just called to me. I thought it was the most exciting sound, and I couldn't imagine what the people were like who made that sound or the part of the country it came from. I'd never been to the south; I couldn't imagine what it was like. It was challenging at first. Guitar was much easier for me; figuring out how to play with picks on was really hard. So it was a little bit slower learning curve on the banjo. But once we moved to San Diego and I got hooked up in the San Diego bluegrass clubs, all of a sudden there were banjo-fiddle contests, then it started to go faster.

Did you ever have a desire to sing?

Brown: When I was growing up I always sang a song in the band, it was never a big thing. But I never felt music was missing anything when it didn't have words. I'd sit and listen to David Grisman's first quintet record—I can't imagine how many hundreds of times I listened to that record—and it seems very complete to me. So it wasn't until I moved to Nashville and began hanging around in this world that I realized that most people think music needs to have words. It never seemed that way to me. It's nice to go play in the British Isles because there's more of a tradition of instrumental music there. You would never have someone over there say, "Just sing one!" the way they do over here. I was called to do this, to write this music and try to make the banjo speak for me. I guess it would be easier to be a singer, but that's not what I do. I appreciate a great singer—sitting in the studio with Dale Ann is so inspiring—and I enjoy singing harmony parts if it's the right thing. But since there's no one in the band who sings that would be kind of weird.

Have you ever written lyrics that you've hidden away?

Brown: Alison Krauss and I wrote one that she recorded a couple of records ago, but I wouldn't say it was a great song by any stretch of the imagination. She and I goofed around with some songs where we wrote some words, but that was the last time.

You really do have a full plate with the toddler, being an artist and running the label. Would you have it any other way?

Brown: No. I'm really lucky to get to do this. I could easily—well, I might not be an investment banker today, but a year ago I could still have been an investment banker. But this is very personally fulfilling. I feel like all of us here have a path we need to be on and a specific talent we can contribute to the world. I feel like I've found my place by not only getting to play my little tunes in front of an audience, but helping other artists get their music out too.

Alison Brown Quartet Live at Vanderbilt: interview and footage from a performance at Vanderbilt’s Blair School of Music

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024