The Miracle Of Jesse Winchester

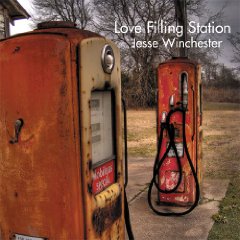

With 'Love Filling Station,' One Of America's Premier Songwriters Primes The Pump

By David McGee

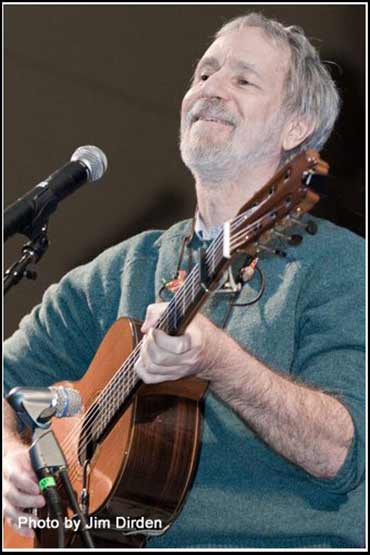

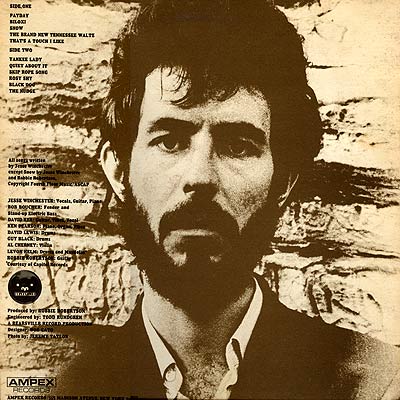

Jesse Winchester: 'I'm not the same person as I was when I grew up in Memphis, but who is? We're all going through changes like that.'In contemplating the miracle of Jesse Winchester (about which more later), consider for a moment how this man has experienced the full ziggurat of the music industry apparatus, from the muscle a major label could put behind an artist it believed in and launch him into a generation's collective consciousness, to the bloodless surgical precision with which it could dispatch the same artist when he failed to produce a suitable yield on investment. Now, having come through the maw of the system, where he vaulted to prominence in 1972 with his Robbie Robertson/Todd Rundgren-produced debut, which contained nothing less than two certifiable American folk-country classics in "Yankee Lady" and "Brand New Tennessee Waltz," he's understandably developed a deep and abiding cynicism towards the machine and its voracious, devouring appetite. Consider, then, where he's come to today, nearing age 65, and entrenched as a bonafide songwriter's songwriter, oft covered, his creations forever sought out by artists seeking to add something of depth and insight to their repertoires, especially when it comes to love songs. This Jesse Winchester tempers his skepticism of the machine with a large dollop of self-accountability, refusing to play the old, old game of woe-is-me-the-label-screwed-me-over litanies.

He admits his major label experience (he was signed to the Warner Brothers-distributed Bearsville label) "made me very cynical about the record business." No sooner does he say this than he adds, in as urgent a tone he can muster in his syrupy, singsong, quiet Southern accented voice, "But you see, it was my fault. I don't know if it's still going on because I haven't been paying attention, but the record companies would sign a young artist who was just grateful to have a recording contract. Someone thinks my songs are good? Hot diggity dog! Forget about percentage points, off this, off the top and once the production costs have been recouped [which he pronounces "re-coop," a lingering reminder of his many years spent in French-speaking Montreal, where he retreated in 1967 rather than serve in a war in Vietnam he considered immoral and illegal], etcetera, etcetera. You don't notice all that. It was just a system that was geared to make money for everybody but the artist. So yeah, that bothered me, but by the same token I went into it with my eyes open. No one held a gun to my head. I did it for ego, and I did it for pride, so I can't really blame anybody but myself."

So Jesse Winchester, having thrown off the yoke of major label servitude while having had the scales fall from his eyes in terms of his own complicity in his fate, embraces his inner exhibitionist; this most gentle of souls, the most self-effacing brilliant songwriter maybe on the planet, enjoys trotting it out for all to see and judge—"it" meaning himself. On the stage is where, in his own estimation, he is most fully realized as an artist, so much so he can barely relate to his recorded art.

"I can't listen to my own records, so that tells me something," he explains. "I have sort of a philosophy more than anything, a vague feeling that performing is really what you're doing; the writing is geared towards that. I read a piece the other day on the Internet, some musician talking about how record companies were destroying music. You know, what do the record companies have to do with music? Music is never the same way twice. You can't stop the river, you can't stop music. It's a living thing. It's like saying music began with Thomas Edison. It just doesn't make any sense. Music is a performance—I never get that magic from a record that I do from a live performance, that sensation when you feel like time has stopped. That sort of thing doesn't happen with me with records. Records to me are more compositional art or construction art, I'm not sure how I would describe it. But it's not quite the same thing as music; music is involved, I guess. I don't really know what I'm talking about, but I have the feeling that the record business is not the be-all and end-all of it, and certainly in my case that's true. The small sales of my records say everything that needs to be said about my skills as a recording artist. I guess I sort of have to rely on my performing and it's been really fun and gratifying to me."

Jesse Winchester performs "It's a Shame," from his new album, Love Filling Station, at the Savannah Folk Music Festival, November 2008And so it was on April 21 that Jesse Winchester brought his performing self to New York City's Joe Pub, for his first Gotham appearance in more than a decade. Nearly a full house was on hand, and all were primed for the miracle of Jesse Winchester. That is to say, to absorb, to luxuriate in, to be moved by and even to cry to the songs crafted by the lone, wiry, grey-bearded figure on stage, seated on a barstool, acoustic guitar in hand, rather preppily attired in khakis and a sky-blue sweater, two mics at the ready and a clutch of songs to offer. Songs of beauty and wry humor, songs of startling intimacy and searing poignancy, songs of sepia-tinted nostalgia for the southland of his youth and memory, rooted both in a time long passed and right here and now, words of love and terms of endearment, Yankee ladies and Southern belles, a veritable love filling station of characters, some full up and needing only to top off their tanks, some half empty, some—likely a majority—running on fumes. He rolled out a tender "Talk Memphis" ("my personal anthem"); a hilarious reading of "It's a Shame About Him," a song from his new Love Filling Station album about a poor sap the folks just can't stop tsk-tsking over about his run of bad luck and cluelessness; a stunning, tender rendition of "Sham-A-Ling-Dong-Ding," also from the new album, a touching chronicle of an eldery couple's romance spanning youth to old age, sung in that high, fragile tenor built to break hearts, its immaculate lyrics rendering the audience mute, dead silent, taking in every subtle nuance and telling twist of phrase; launched into a high-spirited gospel number, which he introduced as such and promptly announced, "And then we'll drop the subject because the Lord has a way of casting a pall on a party." A heart-tugging interlude ensues, with Jesse's clear, high tenor caressing the winsome, saloon-style ballad, "Lonely For Awhile," with the crowd pleasing lyric, "You revolutionized my thinking/And now I have a whole new style." The classics followed: the majestic "Brand New Tennessee Waltz," as wrenchingly beautiful a work of art as ever; a soft, contemplative "Yankee Lady"; the buoyant "Nothing But a Breeze," and somewhere along the way he managed to observe, "I don't know what happens to people who won't make concessions to the male ego."

But the real stunner wasn't even a song so much as it was Jesse himself, when, at the end of his set, he interrupted—and there is no other way to describe this moment—a rousing, a cappella gospel workout by breaking into a confounding, convulsive dance. It was part funky chicken (honoring his Memphis roots, perhaps), part Robot, and way to much of the herky-jerky non-style immortalized by Seinfeld's Elaine Benes, which led to a running joke throughout the series' subsequent episodes, in which the show's other characters would ask, upon hearing Elaine say she had been to a party, "You didn't dance, did you?" Thus a genuine WTF moment at a Jesse Winchester show at Joe's Pub in Manhattan, the artist having his feet in Dixie, his head in the cool, cool north.

This too is part of the miracle of Jesse Winchester, albeit of a lesser magnitude than the miracle of his gift of song. The Lord works in mysterious ways, disdaining to cast a pall on the party when Jesse's gyrations gave Him every reason to do so. It was the right call.

***

The cover of Jesse Winchester's 1970 debut, produced by Todd Rundgren and Robbie Robertson: 'Someone once said she had heard that I was famous, and then said, 'Can you tell me something you did that made you famous?' Putting a record out is sort of like having my nose rubbed in that feeling.'Reflecting on his first visit back to the U.S. following President Jimmy Carter's 1976 amnesty for draft resisters, Jesse said coming back home had made him realize that in exile he had become "far gone Canadian." In 2002, he came back for good, returning to Memphis, where he met and married his third wife, Cindy, with whom he now lives in Charlottsville, VA. Despite his years in Canada, he says he was never very far from home.

"I remind myself of the smart aleck who goes to Europe and then comes back to Des Moines and sort of lords it over everybody because he's so smart and experienced now," Jesse says. "No, but I'm not the same person as I was when I grew up in Memphis, but who is? We're all going through changes like that. Living in Canada did affect me in so many ways I couldn't even start to describe. Even musically, living with the French people, learning about the great French singer-songwriters, Piaf, Aznavour, powerful performers out there by themselves, delivering up their souls to people—just being exposed to that was good for me. I learned a lot from those people."

After becoming a Canadian citizen in 1973, Winchester remained in Montreal following the Presidential pardon, and from there fashioned a sterling catalogue of work for the Bearsville label and became an oft-covered songwriter even if his own acclaimed albums didn't storm the charts' rareified zone. But after a steady output of seven albums between 1970 and 1981, his recording activity slowed dramatically: almost seven years passed before the release of 1988's Humour Me, another 11 prior to the release of 1999's Gentleman of Leisure. (Winchester's home demos of the Gentleman of Leisure songs have been collected on a CD, Rough Ideas, available through www.jessewinchester.com/shop.shtml.) In the oughts, his catalogue shows but two albums, both live efforts, 2001's Jesse Winchester Live at Mountain Stage, and 2005's Live, preceding the new Love Filling Station on the activist-oriented Appleseed Recordings, home to a burgeoning and impressive roster of mostly veteran artists whose work often reflects a sensitivity to topical or spiritual themes, including Tom Paxton, Donovan, Pete Seeger, Sweet Honey In the Rock, Holly Near, Tom Rush, David Bromberg, Angel Band and others.

Though his comments would indicate he records only grudgingly, as a way to have something new to offer audiences when he performs live, in explaining the gaps between his later albums Jesse admits the actual process of studio work—the writing, the bonding with musicians in the studio, the arrangements coming to life—is enjoyable, "the fun part." It's the getting to it that's difficult. "I'm just glacially slow," he said via phone from his Charlottsville home.

There's more where that came from. As simple and direct as his songs are—"I'm a guy who likes to ride the middle/I don't like all this bouncing back and forth," he sings in "Nothing But a Breeze"—his answers to interview questions trend towards two poles: multi-layered or whispered, taut responses with puzzled overtones, as if he has a cartoon balloon with a question mark in it hanging over his head. (To be fair, let's take into account his interlocutor's questions, too, when considering his answers.) So the matter of his extended sabbaticals from recording turns out to be rooted in his distaste for the ensuing chest-thumping necessary to call attention to the work.

"Trying to convince people to love you and buy your record and that sort of thing is hard to do for me," he says by way of expanding on his opening gambit. "Certainly better than working for a living, but even so, that part of it. I'm not a very popular singer or writer; I'm sort of marginal. I don't know how to put this, but it's hard for me. Someone once said she had heard that I was famous, and then said, 'Can you tell me something you did that made you famous?' Putting a record out is sort of like having my nose rubbed in that feeling. Alan Edwards at Appleseed wrote a great blurb for the CD, and he asked me why I made the record, and my answer then was, 'Because my wife kept bugging me.' And that's about as accurate as I could get. I couldn't get any more honest than that."

But he can. And he does.

"I went through a big life change by moving back to the States and marrying again. All of that sort of ate into my writing time. More than that, it just focused me on another area of my life that maybe hadn't had any focus before. But that's just an excuse; I really don't know the answer."

In the end, so what? Love Filling Station exists, and furthers the miracle of Jesse Winchester. It's no simple matter, this miracle, because it manifests itself in the exquisite songs he has been fashioning lo these 39 years since his debut. Whether anything will jump off Love Filling Station and become another "Brand New Tennessee Waltz" only time will tell, but it says here the album contains several songs suitable for admission to the pantheon of Winchester classics. None may be more perfect to enter exalted realm than the aforementioned "Sham-A-Ling-Dong-Ding," with its doo-wop style dreaminess and exquisitely realized lyrical reminiscences of a couples' love affair evolving from the awkward teenage years to old age, as sung, seemingly, by the elderly man of the pair, whose public displays of affection towards his bride provoke tut-tuts from their old folks' home neighbors.

To this interpretation, Winchester says: "I never thought of that."

I thought it was being told by a couple of elderly folks who are being made fun of by the others in the old folks home for being so demonstrative in their physical affection for each other. They're looking back on teenage love but seeing it from the perspective of an elderly person.

"That could definitely work," he asserts. "I thought of the singer as talking to a girl who was maybe his first love as a teenager, but they're older now. I don't know. It all works."

Take note: this is not Jesse being difficult but rather reacting to interpretations of songs he wrote with another theme in mind. It's part of the mystery of music, how the composer intends one thing but the listener hears another. Consider the following exchange:

When you put these songs together, and the three covers, did you sense a binding theme in your original songs and did that affect the choice of cover songs?

Jesse: No. I had no grand scheme in mind at all. It's after the fact—you're the second person to point out the title and the preponderance of songs about love. I really never gave it a thought. But it's true. That's what the songs are about.

One of the things that jumps out at me is a mini-sequence of songs within the larger sequence, where love ends or has fled, but there's no bitterness. These are truly gentle, poignant memories of love that has passed-"I'm Gonna Miss You Girl," "Lonely For Awhile," even "I Turn To My Guitar." They're almost like chapters unto themselves. But you didn't hear them that way? There's no purpose in the sequencing?

Jesse: No, the sequencing I do, and I try to keep songs that are in the same key, you know. I don't really think about that sort of thing, which is sort of neat, isn't it?

But this perspective on love that doesn't last, is that you talking or you reflecting on ideas and experiences you've noted in others?

Jesse: I've definitely been around the block romantically speaking. Certainly not in the number of ladies, but more the number of wives. My first divorce just leveled me; I mean I was mentally ill, really, for awhile. I had never known that kind of pain before. You know, I've been all over the place, but as I get older—I don't know whether it's wisdom or just laziness—I'm too lazy to misbehave. I'm tired of going around cleaning up after myself with the mistakes I've made. I think that's it. Whatever it is, I seem to be better at marriage and am working a little harder at it. It's true that, as Joni Mitchell sang, I've looked at life from both sides now.

Are there songs you can point to on this record that are a direct reflection of how you feel now, or are they all that way?

Jesse: Well, there's a sort of light song, "Bless Your Foolish Heart," that gets pretty close to where I am.

That struck me as a song written by a musician who knows how difficult it can be to live with a musician.

Jesse: Absolutely.

I think one of the things that led me to believe there might be some kind of concept in mind was the placement of "Far Side Banks of Jordan" on the record. That's about love enduring beyond the grave and it's been quite a ride for the listener at that point, from the beginning exuberance of new love in "Oh What a Thrill" to love eternal in "Far Side Banks of Jordan." We have experienced so many varieties of the love experience at that point.

Jesse: That's true. That's true.

Is this a song you've carried with you for awhile? Been a favorite? It's the last song I ever heard Johnny Cash perform live, at the Carter Family Fold in Maces Springs, Virginia, about a year before his death. Your version is so powerful and I thought, He's really wrapped it up neatly here.

Jesse: I'm glad we had this conversation!

Yeah, you can take credit for it.

Jesse: I just might.

An American classic: "Brand New Tennessee Waltz" by Jesse WinchesterIn an interview early in his career, Winchester opined that in his songwriting process the first verse, "the inspirational verse," was the easiest, then came the hard part of crafting other verses to complement the first. Over time his approach has changed, strikingly so, from what it once was.

"It's the reverse now," he says. "I would say the first verse is hardest, because that relies on inspiration, which you can't control, you have no power over that at all, even whether it's going to come at all in the first place. When, where and are you going to remember it the next morning, that sort of thing. That's the hard part; the easy part is sitting down and expanding on that idea. That you can do. You can show up every day and work an eight-hour day to do that kind of thing. Making sure stuff rhymes and scans properly, the point of view stays consistent, etcetera. That part I'm okay with, but when you're waiting around for that first line to show up, it's nerve wracking."

All in all, Jesse Winchester is in a good place today. He has a nice life in Virginia, with Cindy, who is clearly the spur he needs to get on with it, and provides counsel, a kick in the rear and unwavering support (she travels with him and works his merchandise table at shows), and the evidence on Love Filling Station is that his songwriting artistry remains at an apex. In the abovementioned 1977 Montreal radio interview, he was asked whether he stood by his axiom, "It's not the decisions you make but how you live with them." Thirty-two years later, he says, indeed, it's true, "one hundred percent.

"That's been my experience with the whole draft dodging thing. I meet guys who went to Vietnam all the time and we hug and call each other brother. God doesn't come down and pronounce on these things-'you were right and you over there were wrong and that's the way it is, sorry for you.' Being from the south, we're used to loving people who screwed up in a huge way. We're proud of people whom a lot of people consider traitors. We're proud of 'em, we love 'em! We cheered a hundred years too late for the victories at Bull Run and what have you. Most of the people who disagree with me about the draft thing are very calm and reasonable about it. There's no rancor."

So are you going to quicken the pace of your recording career now?

Jesse: I don't know.

Love Filling Station. Get a full tank now; it may be awhile before you come to another one.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024