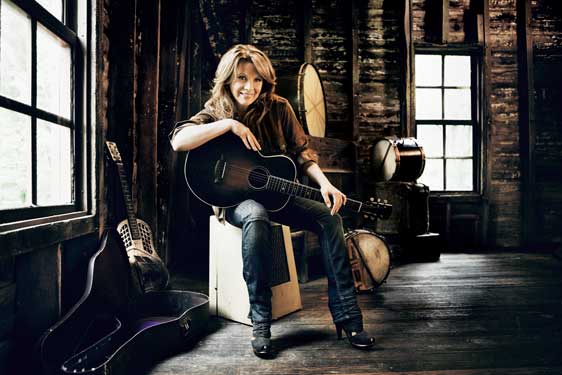

Patty Loveless: Sometimes the truth is simply the truth, unembroidered and unambiguous.The Heart Is A Priority

By David McGee

MOUNTAIN SOUL II

Patty Loveless

Saguaro Road RecordsPatty Loveless has a real problem here. She’s so good she’s making this sound entirely too easy. Like another great country artist honored in this issue (Dolly Parton), Loveless shows no sign of diminishing gifts. If anything, she sounds even more assured, and more intimately involved, with the material on her new album than she did even with the great classics she interpreted with MVP-like presence on 2008’s Sleepless Nights. This daughter of a Kentucky coal miner brings an extra measure of feeling to the tunes she assays here, perhaps as a result of the laid-back setting husband/producer Emory Gordy Jr. cultivated in the studio; perhaps as a result of the all-star musician lineup simply being at home as much with the material as with each other; perhaps owing to the songs themselves cutting so close to the bone of working class country and mountain living. Familiarity may well have bred comfort here, too, in that on three occasions Loveless returns to songs she has recorded earlier in her career, in contemporary country settings (“Half Over You,” first heard on her 1987 self-titled debut; and from 1990’s On Down the Line, “Blue Memories” and “Feelings of Love”). Whatever the reason, Loveless is absolutely feeling it. As with Dolly, trying to explain some performances is a futile undertaking. Sometimes the truth is simply the truth, unembroidered and unambiguous. So when the ache in the singer’s voice is as plaintive and near-palpable as it is when Loveless sings to a reckless fellow who’s paying for his wanderlust in the currency of haunting loneliness in the Jon Randall-penned “You Burned the Bridge,” what’s left to say except, “Yes, that’s the way it is. Live with it.”? Or an equally, if not more complex archeological dig into the tangled roots of true love, “Bramble and The Rose,” a loping beauty of an Appalachian-tinged ballad that finds Loveless with a Carter-like cry in her voice that is positively chill-inducing. By contrast, the resolve in her stance to rise above hard times in Harlan Howard’s classic “Busted”—which features the often-omitted lyrics referencing life in a coal mining community—dashes most interpreters’ usual hopeless air in favor of an undaunted survival instinct. Where there is will in one song there is equanimity in another: the churning honky-tonk breakup saga, “When The Last Curtain Falls,” rises Heavenward on keening twin fiddles and plaintive, soaring harmonies, the combined efforts suggesting, all at once, the numbing impact of parting (“with a silence so loud/we can’t feel at all”—at which point Rob Ickes bursts in with an arpeggiated dobro lick that approximates the sharp stab of betrayal) and a sanguine acceptance of moving on as the first step towards healing (“there’s no reason or cause/to cheer or applaud/when the last curtain falls”). On the gospel side, Loveless gets it going on what amounts to a mini-set six songs in, starting with a sprightly down-home bluegrass reading of “Working On a Building,” wherein all the help she needs comes by way of Del McCoury’s unflagging rhythm guitar and son Ronnie McCoury’s darting mandolin lines, with Del leaning in to do his part singing some gritty leads and harmonizing with Loveless when she isn’t taking the whole affair into the ozone. Vince Gill (baritone vocal) and Rebecca Lynn Howard (tenor vocal) shadow Patty’s fervent, crying lead vocal on the stirring a cappella cry, “Friends In Gloryland,” then the Burnt Hickory Primitive Baptist Congregation add a bottom-rich, rumbling chorus to Loveless-Gordy’s celebratory lesson in faith and resilience, “(We Are All) Children of Abraham.” After this focused spiritual discourse, the frisky, strutting, foot-stomping traditional country of another Loveless-Gordy original, “Big Chance,” is the best kind of elevating moment, even if the subject matter concerns family discord over a daughter’s unpopular (with the folks, that is) choice of a mate (“he’s the prettiest in these hills/if I don’t hitch him/some gal will/you just messed up my big chance for married bliss and true romance”). And at the end, Loveless returns to the spiritual benediction of an afterlife reward in Emmylou Harris’s solemn, moving “Diamond In My Crown,” with both women’s voices blending to convey the blessed assurance of their ultimate reward, sung with stirring conviction to the soothing hum of an an 1849 vintage pump organ.

Patty Loveless, ‘Bramble and The Rose,’ from Mountain Soul IIAside from Loveless herself, the stellar band she and Gordy assembled for this project gets ample opportunity to make statements too. See above, in the reference to “When The Last Curtain Falls,” for one of Rob Ickes’s more memorable moments; another occurs in the thumping “Blue Memories,” when he has a couple of startling turns, as does Stuart Duncan, who lets out a righteous fiddle cry near the beginning and the end of the song. In the mournful “Prisoner’s Tears” the thick, ominous atmosphere is shaped primarily by the soulful cry of Al Perkins’s elegant steel guitar and the heavy, top strings pulsing of Tom Britt’s electric guitar, with Ronnie McCoury’s mandolin and Deanie Richardson’s fiddle adding tasty, discreet punctuations along the way to enhance the singer’s earnest appraisal of the incarcerated’s abject remorse. When you can call on folks such as these—as well as the great Del McCoury Band fiddler Jason Carter, former Del bass man Mike Bub, Bryan Sutton on banjo, Union Station bass man Barry Bales, and progressive bluegrass legend Mike Auldridge on dobro—you’ve got most of the battle won. They don’t make bad records, and they don’t play by rote but by feeling. Suffice it to say, then, that Patty Loveless either rose to their challenge or they to hers, because Mountain Soul II, as did its like-titled 2001 volume, occupies ground both sacred and rare in being true to its aims and making the heart its first priority.

Patty Loveless, in the studio with Rebecca Lynn Howard and Vince Gill, recording the a cappella gospel number, ‘Friends in Gloryland,’ and explaining how the song ‘helped me pull through’Catching Up With Patty Loveless

After last year’s acclaimed covers album, Sleepless Nights, the coal miner’s daughter returns to the scene of earlier triumphs on Mountain Soul II

By David McGee

It was a short, sweet conversation, and worth every minute of the time spent. During preparations for her forthcoming tour, Patty Loveless took a moment to chat about how Mountain Soul II came to be and something else near and dear to her heart—her work with the Christian Appalachian Project (www.christianapp.org/), which helps feed the hungry and provide medical assistance to the infirm throughout Appalachia. (See related story in this issue.)

In the press material that went out with this album you make an interesting statement about how in conversations with fans you found them eager for you to get back to the traditional sound of Mountain Soul, and that they don’t have much truck with contemporary country at all. Is that correct?

Patty Loveless: Well, my audience, my fans, always knew that I had done this form of music in the past. Honestly, if you go back and listen to some of my past recordings, even my very first record I did for MCA, my debut album, Patty Loveless, there’s a song on there that Jim Rushin wrote called “Slow Healing Heart,” which sort of has that feel of Appalachian mountain music; and of course “Half Over You,” which is on Mountain Soul II, I always thought was such a great song that never got the recognition. I wanted to revive it, and especially for my audience. And there’s a record I did called Honky Tonk Angel, also on MCA, and it has a song on it called “I’ll Never Grow Tired of You,” a Stanley Brothers classic. So I have always kind of slid a song like that onto my previous records, and I think a lot of that has to do with the producer, Emory Gordy. I feel that I have one of the finest. Now, he is my husband—we’ve been married 20 years—but we met when he was working as an independent producer and he was working with Tony Brown, and they co-produced three records together on me at MCA. Then when I ended up going to Sony/Epic, that’s when Emory took over as my producer. I always felt comfortable with him. He just knows me, he knows that area that I’m from, and he has nothing but great appreciation for many different kinds of music, but especially for the music of the Appalachians. The first time he heard me sing, Tony Brown told him I was North Carolina, and he said, “Tony, she sounds like she’s from up around Pikeville, Kentucky.” He knew it.

Well, Emory has an incredible track record apart from your recordings. You don’t ever have to apologize for or even explain using your husband as your producer. The results speak for themselves.

Loveless: Exactly. I think what makes him such a fine producer is that he is really and truly such a wonderful musician. He amazes me. He’s always had this perfect pitch. Sometimes he knows how to work with it and knows how to perfect it, but at the same time he knows how to let it naturally evolve. Sometimes even when something sounds like a mistake and I’m going, “I want to re-sing that!” he says, “No! It’s great! Leave it alone!” Sometimes we revisit old records, different forms of music, and you know what, there’s some great records where there were some train wrecks on them but they were awesome.

I wrote a biography of Carl Perkins a few years back, and during our interviews Carl insisted there were “drastic, drastic” mistakes on every Sun record he ever cut, to the point where he claimed he had trouble listening to some of those records. He would be in a minority in that regard. Those are wonderful recordings.

Loveless: That’s what I’m saying, and that’s what I think makes Emory such a wonderful producer. He allows me to run and do what I need to do. And he does his part.

But anyway, back to the record…it was recorded live, just like the very first Mountain Soul record. I think the difference is, as we all very well know, Tater Tate played fiddle and also played upright bass on the first Mountain Soul, and he’s no longer with us. He was just such a wonderful man; and also Gene Wooten, who is also no longer with us, played dobro. But it was a matter of putting some of those who had been around for a long, long time in a room with the up and coming kids on the block. And we did that with Mountain Soul II. There’s a little girl who sang on my Sleepless Nights record, Sydni Perry, she’s just awesome and she held her own in the studio. She had to come in and sing live. On Sleepless Nights she came to my house and put her parts on that record. But on this record, boy, she did hold her own. She was singing with Carl Jackson and Ronnie McCoury. They all were very impressed by her. Then you take Carl Jackson, Vince Gill, Rebecca Lynn Howard, Rob Ickes and mix them with Mike Auldridge, Bryan Sutton, then you have Emory, Al Perkins on steel, Tom Britt on electric guitar, Jason Carter on fiddle, Deanie Richardson, who’s out with me, on fiddle—it was quite a mixture. I mean we just had the time of our life in there. We’ve all at one time or another worked with each other. Del McCoury was the daddy of us all—I hope I’m that young when I’m 70 years old. A room lights up when he walks in; just with that smile of his, a room lights up when Del walks in. Same with Dolly Parton—she lights a room when she walks into it. It’s just spirit. You can feel it in them when they walk in.

It was all cut live, but Emmylou had to put her vocals on after the fact. We cut “Diamond In My Crown” here at the house; Emory played an old pump organ, it’s an 1849 pump organ that his mother had given to him for Christmas in 2003, and he ended up playing it on “Diamond In My Crown,” the last song on the album.

It’s a perfect ending, too, a capper on the statement you’ve made up to that point.

Loveless: Yeah, we don’t really think about the sequence until after the fact. The songs do it themselves. For this record you almost have to listen from the very first song to the very last one to just get the whole package. It’s not a singles kind of thing, where you can go in and listen to one or two songs. It’s a whole package; it’s a story; it’s like opening up a book and reading it. And a little bit about my life. I hope I’ve taken people on a really wonderful journey with this record.

‘This record is not a singles kind of thing, where you can go in and listen to one or two songs. It’s a whole package; it’s a story; it’s like opening up a book and reading it.’What about gathering the material? Was it a long process picking the songs, or did you know what you wanted on the album when you decided to do this volume?

Loveless: Well, honestly, when the label came to us wanting to do another record, I was still in the Sleepless Nights mode. I wasn’t really ready to go into the studio and do another record right away. It had not even been a year yet since Sleepless Nights was released. So we presented this idea to them again about there being a lot of popular demand, for another Mountain Soul. I sort of had to be talked into it, to tell you the truth, because I wanted to be a little more prepared. Then we started listening to songs, I guess in January. Then Emory and I wrote “(We Are All) Children of Abraham,” but some of these songs we cut in an acoustic manner, such as “Half Over You,” “Handful of Dust,” I sort of had to be convinced to cut “Blue Memories” with a more “grassy” feel. It actually was a single for me from the On Down the Line album, from 1990. It was so hard for me to get away from that particular version. When I got in the studio and ran it over with Rebecca Lynn and Vince, they convinced me it could be done that way, and Emory was going, “Oh, it can be done, honey, trust me.” Another song, “Feelings of Love,” was on the On Down the Line album as well. Emory had heard that particular song—actually he didn’t remember it being on the album. He was viewing YouTube one night and I had done it acoustically with John Denver on a John Denver Christmas special. Emory just loved that whole feel and that’s what he wanted to do, and we had Mike Auldridge playing dobro on it. It’s very fitting for what’s going on in our lives today. Those material things don’t really mean that much anymore. You gotta stop and think about people, and the one thing we can give that doesn’t cost anything at all is love. When somebody feels loved, I think that’s one of the most wonderful gifts that God has given us, the ability to love.

That’s an interesting note to segue into something else you’re involved in, meaning the Christian Appalachian Project. On the CAP website you’re offering free download of “Working On a Building” in return for a donation to CPA. I know you’re the daughter of a coal miner, so let me ask two questions that may have one answer: Why did get involved in this and what does it mean to you to help the people of Appalachia?

Loveless: When I think about my family, my mom and dad provided for us by working in those coal mines. He passed away in 1979 from complications from health problems from working in the coal mines—he had developed black lung, and his whole body had begun to deteriorate. He was only 58 years old. I see a lot of families living in a lot of poverty there. Sometimes the beauty of the mountains tends to hide some of that poverty. Sometimes you can’t see through those beautiful trees until about fall, when the leaves start to fall. Then you start to see the deterioration. When you think about when strip mining was going on in Kentucky, a law was finally passed, in the latter part of the ‘60s, I believe, that a lot of the mine operators were responsible for restoring the contour of the land, and replanting at least 70 or 75 percent of that surface. I knew mama and daddy struggled, and we had hard times, but it wasn’t like a lot of those folks back there in the mountains. That’s the reason I felt good about having the opportunity to give something of myself, and what that is is music. It’s really wonderful to know that I’m able to give through music to make people aware of some of the problems, the issues, people are facing in Appalachia. You know, it’s not just Kentucky and Virginia and West Virginia. There are places in North Carolina, Tennessee, too, that are hurting. Christian Appalachian Project is doing everything they can to help with the medical situation, getting some of the elderly people to doctors and providing food and housing, just trying to help. To me that’s doing God’s work; that’s why people are here for each other. I feel a part of what God wants us to do, and that is to love one another and be there for each other. It’s good to be a part of something like this. I think it’s wonderful what they’re doing.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024