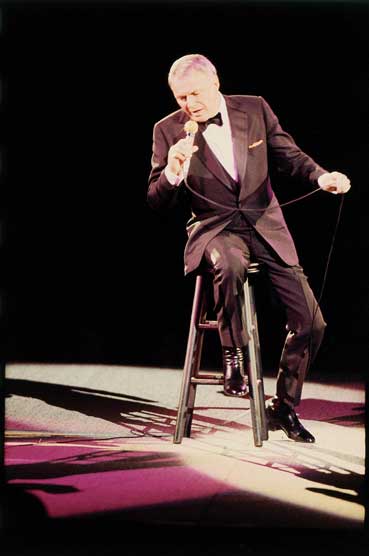

The Chairman of the Board, at the Meadowlands, 1986: What a night, what an artist, what a memento of our greatest singer in his autumn years, making all the necessary adjustments to bring new grandeur to his treasured songbook.

It Was More Than A Very Good Night

(An Autumnal Report From the Chairman Of the Board)

By David McGee

LIVE AT THE MEADOWLANDS

Frank Sinatra

Concord Records

It was a rainy night in March, 1986, when 70-year-old Frank Sinatra, his band and orchestra, led by pianist Bill Miller, settled into the Meadowlands Arena in New Jersey—"my home territory," as Sinatra would later refer to it in front a rapturous sellout crowd—for a one-night stand that would become the stuff of legend, still a hot topic among Sinatra-philes who debate the high points of his later years but mostly agree that this particular performance in the Garden State was nigh on to incomparable. Now, much like the 1959 recordings from the Chairman of the Board's pit stop in Australia that didn't surface on disc until 1997 and were instantly revered for the portrait they offered of the artist at work in a more intimate setting than usual (Sinatra was backed only by a small combo led by Red Norvo), this Meadowlands performance need linger in historical limbo no more. It too should be duly celebrated for the portrait it offers of the artist as most saw him in his lifetime—in front of a stellar combo and orchestra, offering one gem after another from the Great American Songbook, engaging the audience with warm, collegial banter, and essentially putting on a clinic of smart, deeply engaged vocal artistry that appeals to both the head and the heart, although the latter clearly prevails when all is said and done. The great voice is a bit ragged at times, kind of rough around the edges, but more often than not it's warm, full of life and energy, and powerfully imbued with the reflective quality Sinatra brought to these great songs all through his long career, whether he was the brash beanpole singing idol of '40s bobby soxers or the smartly tailored, earthy—and, let it be said, occasionally abrasive—elder statesman of song. He wasn't a fount of wisdom or a piercingly insightful philosopher in conversation (it's probably better for his image that he did so few in-depth interviews, although author John Rockwell did draw him out brilliantly in their music-centered discussions for the coffee table book, Sinatra: An American Classic, published by Rolling Stone Press in 1984), but he certainly was when he sang, when he took the poetry of the Gershwins, Cole Porter, Harold Arlen, Jule Styne, Johnny Mercer, Rodgers and Hart, Sammy Cahn, and the songwriter whose work he most favored in his career, Jimmy Van Heusen, and found something in it even deeper and more telling about the human condition than the words on paper suggested.

This latter is the Sinatra of Live At the Meadowlands. That is to say, this outing, as overwhelming as it must have been to have experienced it in person, is one of the artist's great performances-mull that over for a bit-and one of the best live albums ever released, simply put. The recording quality is superb; the audience greets Sinatra's entrance with thunderous, uproarious applause, and then is heard mostly in muted shadows for the rest of the disc, until the Chairman bids them adieu following a boisterous, belting rendition of "Mack the Knife," when the band kicks into a rousing reprise of the "New York, New York" theme; only then does the assembled multitude make its presence felt again in an overt way, with an ecstatic ovation and excited shouts. The focus, you see, is always on the voice, and the music.

'Come rain or come shine'

Anyone listening to this performance surely will be struck with Sinatra's pride in repertoire. Always a champion of first-tier songwriting and arranging, he makes certain those on hand know it's not all about him when he sinks his teeth into one of the exceptional numbers in his set. He always did this, but as the years rolled on the appreciation evident in his attributions grew more pronounced—he knew he was working from an unparalleled artistic plateau when he found these songwriters, along with arrangers such as Nelson Riddle, who comes in for more than a couple of loving citations on this occasion. Following a slow boiling "Where or When," as the audience bathes him in applause, he says thank you, then adds, "Rodgers and Hart," as if to place the patrons' appreciation in its proper context; after Rodgers and Hart's tender, "My Heart Stood Still," he exclaims, "Isn't that a pretty song? What a marvelous love song. Thank you!" once again making certain the songwriters are given their due. Before performing "Change Partners," he gives props all around, even, comically, to himself: "This is a song written by Irving Berlin, orchestrated by Joe Parnello, and it was introduced by Fred Astaire, whom I taught every step he knows." And as the music pulsates at the outset, he offers an aside—"Good song"—before easing into a deliberate, uptempo incantation of the yearning lyric in a strikingly different arrangement, pretty much free of the Latin inflections in the first version of it he recorded on 1967's Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim album, as arranged by Claus Ogerman.

'Change Partners,' Frank Sinatra and Antonio Carlos Jobim, from their 1967 album, Francis Albert Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim. On Live At the Meadowlands, in an arrangement by Joe Parnello, Sinatra approaches the song less casually, with a deliberate, uptempo incantation of the lyrics, minus the Latin inflections in the original arrangement. 'Change Partners' is part of a medley of songs performed in this clip, including 'The Girl from Ipanema.'

He proclaims the Arlen-Gershwin "The Gal That Got Away" to be "brought to life by the great Judy Garland, originally," and adds: "Beautiful orchestration by Nelson. Thank you." Before a rousing "New York, New York," a voice calls out from the audience; what is said is indistinguishable on the disc, but Sinatra yells back eagerly, "Yeah, I know what you want to hear, baby—and I think you're about to hear it now!" As the band blasts that incandescent, swaying intro, he doesn't let the moment pass without acknowledging the tune's curriculum vitae: "This song was introduced and made famous by the great Liza Minnelli, it was written by Fred Ebb and John Kander, orchestrated by the late Don Costa, my goombah..." Following that celebratory occasion, he takes a time out to toast the audience, "and simply say that I hope you have in your lives everything that you want, everything you wish, mostly love and sweet dreams, and huggin' and kissin', and all things like that. Salud! Salud!" After further interaction with the audience—he reads a letter from some women in attendance whose first visit to a Sinatra show came when they played hooky from their high school to see him at a New Jersey theater—he can hardly contain his affection for the bluesy, woozy treatment he's about to give "Come Rain or Come Shine," and so offers this prelude: "Great song by Harold Arlen, Johnny Mercer, orchestrated by Don Costa. I love to sing this song! Great song! This is for you."

'Moonlight in Vermont,' arrangement by Billy May (not Nelson Riddle, as the subtitle indicates), from Sinatra's first album with May, 1957's Come Fly With Me. At the Meadowlands, the Chairman introduced it by calling it one of his 50 favorite songs, 'about one of the prettiest states in our great country'; in this clip, his introduction includes this sentiment: 'Yes, sir, bless the musician, because without him a great darkness would come over the land, our emotions would fold their tents, and silently steal away.' You have to be Frank Sinatra to get away with that.

It sounds as if it's a Sinatra recital: "And now for my next number..." You have to respect the regard he has for those who helped him get over, and how well they did it. For all the talk of his overbearing ego, and bad manners on occasion, he sounds very much like a man beholden to the cause; but tipping his hat to those who helped shape his legend in song has always been part of the Sinatra style. At the Meadowlands, there was an urgency to all the credits he rolled out, a decided and sincere attempt to get history right. "This happens to be one of my favorite songs. If you listed fifty songs, I'd have to choose one of the fifty, this one being one of my favorites. This is a beautiful ballad by Billy May, if you please, about one of the prettiest states in our great country." So begins a lovely arrangement of "Moonlight in Vermont," which was written by John Blackburn and Karl Suessdorf in 1943, but arranged by Billy May on Sinatra's wonderful 1957 album, Come Fly With Me, the first Sinatra-May collaboration. Better known for his brassy inclinations, May fashioned an elegant, uber-romantic string-centric arrangement for Sinatra, one worthy of Nelson Riddle at his dreamiest, and the singer responded then as he does here, with a soft, open-hearted, unabashedly lovestruck attitude, caressing the evocative lyrics tenderly, the better to emphasize the beauty of the surrounding landscape, sounding for all the world as if he's really at the scene, awestruck by "the evening summer breeze, the warbling of a meadowlark, moonlight in Vermont." Approaching the first instrumental break, he orders the crew to "light up the strings, they're so good looking." As those strings fade and applause rises, this 70-year-old man finds his youth again. "Oh, I love singing that song! I love it! So romantic!" he declares, in a voice brimming with unbridled joy, wonderstruck by it all. Before a finger-snapping, ring-a-ding-ding treatment of "I've Got You Under My Skin," he says simply, "Cole Porter, Nelson Riddle," and settles into an arrangement speckled with muted cornets, little jabs of trombone, tiny blurts from a tenor sax, and the sound of luminous, gliding strings out of Riddle's "Route 66" arrangement—before the break cuts the musicians loose for an all-out frenzy of horn-driven exuberance. "Pretty song by the Gershwins, arranged by Nelson, pretty song, lovely, lovely song," is his setup for a stunning reading of "Someone To Watch Over Me," a breathtaking display of sensitivity and depth of feeling both in the exploration of the lyrics and in the uncanny phrasing, too, working ahead of and behind the strings, according to the mood he wants to evoke, sometimes simply staying right on the note, adding urgency to lines such as "tell her to put on some speed, follow my lead," coolly winding down to a soft landing of such luscious, aching grace it spurs a tidal wave of applause from the audience even before the song fades out.

For his penultimate number, the Chairman returns from whence he came, introducing himself as "a saloon singer," as he was always proud to call himself, and with it, "the daddy of all saloon songs," meaning "One For My Baby," and adding: "This song was written by Johnny Mercer and Harold Arlen, and it simply tells a story of sadness, frustration, tears, alimony"—the audience laughs—"and, uh, very simply, if you've never seen me or heard me do one of these songs, they tell a story about a poor soul whose chick has split, and left him sitting in a small room somewhere on a side street, for about four or five nights in a row, and he's out of it completely at this stage of the game. Most unhappy. So he decides that maybe if he took a walk he might be able to get back again and mingle with humanity. Talk to somebody." Suddenly he's crooning a weary, "It's a quarter to three, there's no one the place, except you and me..." with only Bill Miller's piano behind him, playing an abject, winsome melody, spare and lonely, for the first four bars, until the strings glide in unobtrusively behind him and Sinatra, and stay there, humming ever so softly, heightening the gloom as Sinatra plays the down-and-out role with a riveting mixture of resignation and aggressive assertiveness, real booze-hound behavior and impossible to resist in all its grand ambition.

'Make it one for my baby...'

That's really the end of the show. Everyone kicks out the jams on a jazzy "Mack the Knife," Sinatra included, and especially guitarist Tony Mottola, whose frisky, darting lines and chordings are like a dazzlingly colored hummingbird flitting through an incrementally expanding arrangement, as the horns gather, blowing and bawling, and the rhythm section drives everything forward relentlessly. Sinatra leaves the text to improvise his own verse, name checking other great "Mack" interpreters—Louis Armstrong, Bobby Darin, "Lady Ella, too"—and citing them for singing the song "with so much feeling that ol' Blue Eyes, he ain't gonna add nothin' new." Then, in a graceful segue apropos of his modus operandi on this night, he once more acknowledges his safety net, his benefactors, and even pokes a little fun at his own infamy, to wit: "But with this great big band right behind me/Swingin' hard, jack, I know I can't lose/And when I tell you all about Mack the Knife, babe, it's an offer you can't refuse. We got Don Baldini, we got William Miller, we got Tony Mottola, Irv Costa bringin' up the rear/All these bad cats are in this band now/They make the greatest sounds you ever gonna hear," and seamlessly right back into the final Weill-Blitzstein-Brecht closing verse. Needless to say, the big ending is exactly that—huge and booming, triumphant and celebratory, and electrifying. Sinatra and strings, Sinatra and brass, a swingin' soiree, subtlety, nuance, grace, humor and warmth—what a night, what an artist, what a memento of our greatest singer in his autumn years, making all the adjustments, born of age and experience, required to bring new grandeur to his beloved songbook. Everything old was new again, Sinatra included. Wow.

Frank Sinatra, 'New York, New York'

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024