REMEMBERING MARY TRAVERS:

A PERSONAL REMINISCENCE

By Ira Mayer

The photograph of Peter, Paul & Mary singing at the March On Washington that became the back cover for their second album is so imprinted in my mind that I don't know anymore if I actually heard the performance live on TV or just read about it and saw it in film clips over the years.

It hardly matters. I was 11 that summer, and thanks to my older sister and her friends, I knew PP&M from their albums. Truth be told, I was more a Chad Mitchell Trio fan at the time—they were more overtly political, and they were regulars on the Hootenanny show on TV. It wasn't until a few years later that I learned PP&M were boycotting Hootenanny because the show wouldn't allow Pete Seeger on—the McCarthy era being not so far in the past.

An astonishing performance of ‘If I Had a Hammer,’ introduced by Pete Seeger

But while the Chad Mitchell Trio sang a mean protest song (and in glorious harmony, at that), PP&M put themselves on the line, marching for civil rights, and later against the Vietnam war. Truly there was nary a liberal cause for which they didn't make themselves available, their own glorious harmonies put in service for generally more subtle but no less meaningful pleas for peace, justice, and human rights.

The group was destined to break up as each sought to build a solo career. Mary had been chafing under manager Albert Grossman's tutelage. Grossman insisted she be the strong silent sex symbol of the group. Lanky, with her flowing straight blond hair, she certainly fit the role. But she had a lot to say and didn't want to contain it anymore.

I'm not suggesting Mary broke the group up—I don't know the intimate details. But years of touring, differing interests, families, etc., no doubt mounted into a "time out." Which is all it turned out to be. While each attempted a solo career—and Mary probably fared best on that count—by the time they were ready to tour together again, the talking sexy Mary had been unloosed. Her solo albums were more than pleasant, but her strength—like Peter Yarrow's and Noel Paul Stookey's—was in the mix of voices and temperaments.

Peter, Paul & Mary, 1966, ‘Blowin’ In the Wind’

I saw them as a group live the first time when I was 14, and the passion of what they stood for won me over (not that I gave up on the Chad Mitchell Trio—but that's a story for another time). I saw them as a group for years at their annual Carnegie Hall concerts, as soloists at clubs such as the Bottom Line, at benefits, folk festivals, colleges, and more. When our son was four, and permitted into Carnegie Hall, I took him to hear them, too.

I don't recall if I 'fessed up to Mary that I was part of a trio in high school called Winky, Ira & Marion (as in Winkler Gabriel Weinberg, Ira Mayer & Marion Cohen). We had a well-intentioned but terrible one-night career singing the PP&M catalog. Today, our twenty-something kids and their three cousins go on an annual baseball trip, they all sing the PP&M version of Bob Dylan's "When The Ship Comes In."

Peter, Paul and Mary, ‘When the Ship Comes In,’ 1967

By the mid-'70s when I was reviewing for the Village Voice and others, and working at Record World (the then-competitor to Billboard), I had the privilege of interviewing Mary on the occasion of the release of one of her solo albums. Her daughter Erika was literally crawling on the living room floor as we talked in the apartment she and then-husband Gerry Taylor had on Seventh Avenue in the 50s in New York City.

Now remember, this was the mid-1970s, and one of the things we talk about is how difficult it is to get grandma's recipes right, because "it's a little of this, and a pinch of that," says Mary. "Wouldn't it be wonderful if we could film them making those recipes? Then we'd have it! Of course, that's totally impractical." I don't know if Mary ever got her grandmother's recipes on video. We stayed in touch for quite a while after that, and some time later I was very honored when she asked for a transcript of the interview to refer to in writing her memoir.

But of all the performances I heard by PP&M and Mary solo over the years, one stands out: It was the Weavers' final reunion at Carnegie Hall. An emotionally charged night, to be sure. And the late Hal Leventhal, who managed the Weavers and presented PP&M's concerts, sat me right in front of Mary. I had the Weavers' four-part harmonies in front of me, and Mary Travers adding a fifth part, ever so softly, in my ear. I can still hear her now.

Peter, Paul and Mary, ‘Early Morning Rain’

‘For many of us that sound evokes a distinct period in our lives, humming in the background, right on through the Beatles, the Stones, Hendrix, and all of them.’-–Jonathan Schwartz, WNYC-FM, 09-20-09, four days following Mary Travers’ death, upon opening his Saturday show with two uninterrupted Peter, Paul and Mary recordings.

***

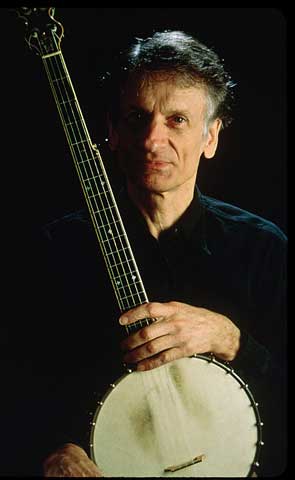

Mike Seeger: Per Bob Dylan, “Romantic, egalitarian and revolutionary all at once’MIKE SEEGER

August 15, 1933-August 7, 2009Remembering the man Dylan dubbed ‘The Supreme Archetype’

By Billy Altman

Hearing the news back in August that musician Mike Seeger had passed away at age 75, my first thought was of the last time I'd seen him perform. It was on a weekend afternoon in June 2005, at the annual Clearwater Festival named for the sloop which Mike's famous older half-brother Pete Seeger first launched in 1969 to shed dramatic light on the rampant industrial pollution that was destroying New York's Hudson River. Like so many other causes big and small that he's put his mind to over the years, Pete Seeger's grassroots campaign to clean up the Hudson against seemingly insurmountable odds had succeeded, and by 2005 not only an increasingly healthier ecosystem but even safe swimming had returned to the historic river's waters. As a result, the overall mood at scenic Croton Point Park in the lower Hudson Valley was especially spirited that year—as bright and sunny as that weekend's June sky.

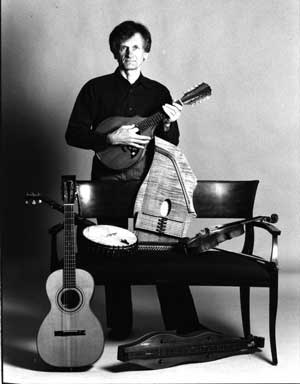

Armed with his usual arsenal of acoustic instruments—six- and 12-string guitars, fretted and unfretted banjos, mandolins, dulcimers, fiddles, squeeze boxes, harmonicas, quills, tin whistles, jawbones, etc.—I watched as Mike Seeger played a typical Mike Seeger set. He introduced every selection from his seemingly endless catalogue of vintage hill country music with a brief history of its origins as a song, the performers who first recorded and/or popularized it, and anything of note about the style or sound of whichever instrument he was playing that was pertinent to either the song itself or the era it was representing. In every case, the result was the same: some creaky old-timey tune like "Hopalong Peter" or "Who Killed Poor Robin" would take on a vitality and stateliness as disarming as it was entertaining. Here was living breathing folklore, right in front of your eyes and ears.

After Seeger's set, I hung around to say hello. I'd met Seeger several times before, most notably at 1989's Sounds of the South conference at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. I'd been invited to participate in several panels as a result of my archival work as creator and producer of the RCA Heritage Series, dedicated to reissuing historic (and in most cases long out of print) pre-World War II folk, country, blues and gospel music. Seeger had been extremely gracious to me at the conference, and his encouraging and complimentary words helped generate significant interest in the series, which, besides achieving critical and commercial success, resulted in a number of gratifying citations for our releases from the Library of Congress' American Folklife Center.

The New Lost City Ramblers perform 'Man of Constant Sorrow' with Mike Seeger on autoharp

As I approached Seeger and extended my hand to him that day, he backed away slightly, then pointed his right elbow at me to touch my right elbow; "musician's handshake," he said with a smile. It was only then, up close, that I realized that this once extremely virile-looking all-American man, who in his youth sported angular features, a full shock of dark hair, and a penchant for button down shirts and leather vests that always made it seem like he'd stepped out of a John Steinbeck novel or John Ford film, now looked somewhat frail. And with a certain distant look in his eyes. I later learned that he'd been ill, though exactly what was wrong was unclear. Suffice it to say that when the news came that his death had come after the proverbial "long battle" with cancer—in his case multiple myeloma (cancer of the blood)—it didn't come as a total surprise.

While he was never quite as well known as Pete, Mike Seeger was in his own understated way as tireless and indefatigable an activist as his iconic sibling. Mike's lifelong cause was the preservation and handing down of music, specifically the music of the Appalachians and the South dating back to the days when music was for average people a participatory activity rather than a passive one. Born in New York in 1933 and raised in Washington, D.C. by his ethnomusicologist father Charles and composer mother Ruth Seeger, Mike grew up in a household steeped not only in music, but in musical tradition: There were frequent visits by such luminaries as Woody Guthrie and Leadbelly, as well as his aforementioned famous older half-brother Pete.

Going into the family business (younger sister Peggy would do so as well), Mike went to New York just as the folk music revival was gaining steam and in 1958, along with like-minded John Cohen and Tom Paley, he formed the New Lost City Ramblers. Guided by (in Seeger's words) "the explicit intention of performing American folk music as it had sounded before the inroads of radio, movies, and television had begun to homogenize our diverse regional folkways," the respect and earnestness with which these young urban Northerners treated their (as it was quickly dubbed) "old timey" Southern repertoire brought them both immediate attention and admiration from the budding young folk generation. Typical of the reverence shown the Ramblers, and Seeger in particular, is this reminiscence from Bob Dylan, found in his 2004 autobiography Chronicles Volume One: "Mike was unprecedented. As for being a folk musician, he was the supreme archetype. He could push a stake through Dracula's black heart. He was the romantic, egalitarian and revolutionary type all at once."

Mike Seeger performs 'Darling Corey'

Seeger and the Ramblers were true pioneers in the "roots" music movement; in unearthing and helping re-introduce vast numbers of songs not heard for decades outside the South, the Ramblers—as his longtime friend singer/songwriter Hazel Dickens aptly put it—"validated our culture." Along the way, they also helped re-discover many of the original artists, including Roscoe Holcomb, Tom Ashley, Cousin Emmy, Eck Robertson, and most notably Appalachian balladeer Dock Boggs.

Mike Seeger, 1995: As tireless and indefatigable an activist as his iconic sibling (Photo by David Gahr)Perhaps even more significantly, though, Mike Seeger also played a vital role in bringing bluegrass music into the 1960s folk music equation. This mostly overlooked part of Seeger's legacy predates even his Rambler days: in 1956, Folkways Records' Moses Asch gave Seeger $100 to drive around the Southeast with his reel to reel tape recorder and document some of the local progenitors of the rolling three-finger style of banjo picking popularized by Earl Scruggs. Seeger's research and travels led to 1957's American Banjo: Scruggs Style, a groundbreaking album that featured 15 different regional banjo players, in particular North Carolina's Snuffy Jenkins, whose playing directly influenced both Scruggs and Reno and Smiley's Don Reno.

The album came out at a pivotal moment in the histories of both country and folk music. As I noted in my 2005 essay accompanying the Legacy box set Can't You Hear Me Callin'; Bluegrass: 80 Years of American Music, the late 1950s found the country music establishment's responding to the raucousness of rock with the decidedly pop-oriented "Nashville Sound," which sought to smooth out country's edges with sophisticated arrangements and slick production values. As country went uptown (and as one of its chief architects RCA's Chet Atkins later lamented regarding the music's identity crisis during this era, "It was the wrong uptown"), acoustic string band music had been all but abandoned by country radio stations and concert promoters who viewed it as too old-fashioned. And even though The Grand Ole Opry continued to feature some bluegrass, it was fast becoming an endangered species. But then a remarkable thing happened: through the efforts of Seeger and kindred spirit Ralph Rinzler, the mandolin player in the New York-based Greenbriar Boys, bluegrass became folk music.

Ironically, late '50s folk enthusiasts began embracing bluegrass for precisely the reasons country music wanted to disown it. The downhome, plain-folk honesty of acoustic string band music, free of commercial trappings and artifice and teeming with a deep rooted sense of tradition, attracted a brand new audience for the genre, especially on college campuses, a circuit that was brand new to the bluegrass musicians, too. Even though the sociopolitical viewpoints of left-leaning folkies and the mostly conservative bluegrassers couldn't have been more opposite, the shared excitement of performers reaching fresh ears and of listeners finding fresh sounds, broke down all manner of barriers. And it was chiefly through the efforts of Seeger and Rinzler that bluegrass became an integral part of not just Newport in the 1960s but ultimately all folk Festivals, right to this day. (It should also be noted that it was Rinzler [1934-1994] who helped Bill Monroe regain his throne as bluegrass' patriarch after becoming his manager; he also discovered and managed the legendary Doc Watson, and later in life, as an assistant secretary at the Smithsonian Institution, was instrumental in the Smithsonian's acquisition and revival of Folkways Records after the death of Mo Asch.)

Mike Seeger performs Elizabeth Cotten's 'Freight Train'

Even though he was fighting cancer, Seeger kept remarkably busy. In 2007 Smithsonian Folkways put out Early Southern Guitar Sounds, which found Seeger showcasing a variety of styles and sounds while performing on 25 different guitars. That same year, Mike appeared on the Grammy-Award-winning Raising Sand collaboration between Alison Krauss and Robert Plant. (That's Seeger on autoharp playing the into on the CD's final track, "Your Long Journey.") And just as his days were ending, Folkways released Where Do You Come From, Where Do You Go? a dazzling box set celebrating the New Lost City Ramblers' 50th anniversary.

I'll end with another memory from that 2005 Clearwater weekend. Folk festivals always include workshops devoted to children's music, and later in the day after Seeger's solo set, I was wandering along the shoreline at Croton Point Park when I heard some very young voices gleefully shouting their noisy barnyard parts in the old standby "I Had A Rooster." Walking over to the stage area, who should I see leading the singalong but the two Seegers, Pete and Mike, strumming their instruments and sharing lead vocals and instructional chores. Engaging the little kids sitting on the grass in front of them, the two brothers were smiling broadly at each other as they sang and played songs from their own childhood for yet another coming generation of Americans. And as I sit here recalling the moment, so am I.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024