Alice In Wonderland 1933: (from left) The Gryphon (William Austin), Alice (Charlotte Henry) and the Mock Turtle (Cary Grant). Alice Liddell, who as a young girl inspired Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’ stories, said of this Norman McLeod-directed version: ‘Alice is a picture which represents a revolution in cinema history!’1933: The Most Memorable Alice

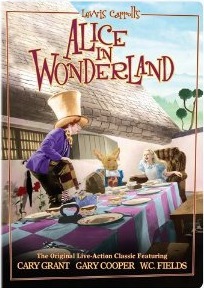

Paramount’s 1933 version of Alice In Wonderland, boasting a budget large enough to lure what was truly an all-star cast for its day—including W.C. Fields, Cary Grant, Gary Cooper—remains, even in this year of our Lord 2010; after Salvador Dali and Luis Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou, after Jean Cocteau’s Beauty & the Beast, after Alain Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad, after Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey—even after Tim Burton’s fabulations in his own Alice In Wonderland box office juggernaut—the most unsettling, the most electrifying, the most hallucinogenic, the most downright mesmerizing of all Alices. Director Norman McLeod’s cinematic vision is the one that dared not merely to suggest but to blatantly unleash the dark shadows barely constrained by the colorful antics of Carroll’s characters and the wary innocence of his Alice, portrayed with beguiling charm by then-19-old Charlotte Henry, a Brooklyn native who had made her acting debut on stage, in the Broadway play Courage, in 1928, and would go on to appear in 31 movies from 1930 until her retirement in 1942.

W.C. Fields as Humpty Dumpty, Charlotte Henry as Alice in the 1933 production of Alice In Wonderland, directed by Norman McLeod, with a big assist from William Cameron Menzies.The release of Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland has knowledgeable film critics reflexively comparing it to McLeod’s 1933 version, which sounds about right for a Tim Burton film—find the most far-out, bizarre antecedent for what he’s doing this time around, and you have a valid point of reference. Burton’s Alice works wonderfully (but it's not Lewis Carroll's "Alice," being set at a later time with an older Alice returning to the world down the rabbit hole to find out what's happened in her absence), thanks in large part to another stellar performance by Johnny Depp, but the 1933 version is the Alice that will neither go away nor be denied. For a multitude of reasons, too. New York Times critic Dave Kehr got it right, at his website and in his Times review of the new DVD release of 1933’s Alice In Wonderland, especially in singling out the vital contribution to the film made by the brilliant William Cameron Menzies. FYI: What neither Kehr nor the TIME Magazine cover story from 1933 below it mention is that the lively musical score for the 1933 version was courtesy none other than the great Dimitri Tiomkin. —David McGee

Here’s what David Kehr had to say of the 1933 Alice at davekehr.com, http://www.davekehr.com/?p=522:“William Cameron Menzies is only credited as a co-writer (with a certain Joseph L. Mankiewicz) on Paramount’s unforgettably odd 1933 adaptation of Alice in Wonderland, but as contemporary press accounts confirm, his contributions to the film, directed by Norman McLeod, went far beyond the script: the expressionistic production design, ingenious in-camera special effects and the thematic focus on a child’s horrified perception of a dangerous, demented adult world all reflect the strong personality that Menzies brought to bear on the projects he touched, in all his different capacities. Finally released in a respectable DVD version by Universal (for years, Alice has been one of the most bootlegged titles on eBay, right up there with the still mysteriously unavailable Island of Lost Souls), the film makes a perfect companion piece to Menzies’ body-snatching bedtime story of 1952, Invaders from Mars.”

Alice in Wonderland, 1933: Alice (Charlotte Henry) encounters the Duchess (Alison Skipworth) and her psychotic, plate throwing cook (Lilliam Harmer). The baby boy, who later turns into a pig, is played by an uncredited Billy Barty, who began his acting career in silent shorts in the 1920s and worked extensively in film and TV thereafter, making his final movie appearance in 2001’s I/O Error [posthumously—he passed away on December 23, 2000]. Barty was also a tireless advocate for the rights of people born with dwarfism.From Kehr’s February 26, 2010, DVD review in The New York Times, in which Kehr did his homework and dug up an effusive quote about the original film from Alice herself:

But only one can boast the endorsement of the original Alice: the 1933 Paramount Alice in Wonderland, being released to DVD by Universal Studios Home Entertainment ($19.98, not rated), the current rights holder. In a Jan. 7, 1934, article in The New York Times, Alice Liddell, quoted under her married name, Mrs. Reginald Hargreaves, expressed admiration for the film that Hollywood had wrought from the story Carroll had invented for her some seven decades before.

“I am delighted with the film and am now convinced that only through the medium of the talking picture art could this delicious fantasy be faithfully interpreted,” she declared, her words possibly burnished by a Paramount publicist. “Alice is a picture which represents a revolution in cinema history!”

Mrs. Hargreaves might have been overstating the case, but the Paramount version, directed by Norman McLeod from a screenplay that uses episodes from both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, remains among the most faithful and insinuating of the dozens of films and television shows derived from the source material.

For baby boomers who first encountered it on television in the 1950s, the Paramount Alice, with its ominous atmosphere, distorted sets and cast of contract players (including Cary Grant, Gary Cooper and W. C. Fields) hidden behind heavy, outlandish makeup based on the famous John Tenniel illustrations, represented something closer to a horror movie than a benign children’s fantasy.

Seen today, it’s still a profoundly creepy experience. This Wonderland is not the proto-psychedelic playground of the 1951 Disney animated version, but a distorted, claustrophobic environment populated by menacing, bizarre figures. The Mad Hatter (Edward Everett Horton) and March Hare (Charles Ruggles) seem less like lovable eccentrics than recent escapees from Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island, fully capable of exotic, unspeakable acts.

Alice in Wonderland 1933: NY Times critic David Kehr says of this scene: ‘The Mad Hatter (Edward Everett Horton) and March Hare (Charles Ruggles) seem less like lovable eccentrics than recent escapees from Martin Scorsese’s Shutter Island, fully capable of exotic, unspeakable acts.’The transformation of the howling baby (played by the dwarf actor Billy Barty) into a squealing, squirming flesh-and-blood pig could be an outtake from Tod Browning’s 1932 Freaks. And the croquet party hosted by the Red Queen (Edna May Oliver) turns into an Ubuesque scramble of authority run amok, in which the terrorized participants (“Off with their heads!”) flail around in violent desperation using actual flamingoes as mallets. (The end credits bring no comforting reassurances from the ASPCA.)

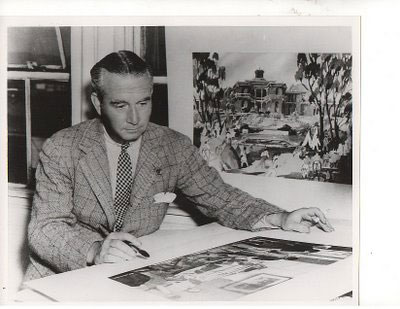

Although the project originated with McLeod (an unobtrusive studio functionary best remembered for his Marx Brothers vehicles, Monkey Business and Horse Feathers), the dominant creative force appears to have been the brilliant, unclassifiable art director, William Cameron Menzies, shown above in his studio.By 1933 Menzies had become known as Hollywood’s leading production designer (a title he is sometimes said to have invented for himself) for his work on elegantly stylized films like Raoul Walsh’s Thief of Bagdad (1924), starring Douglas Fairbanks, and The Bat (1926), an early dark-old-house mystery directed by Roland West. His work on Gone With the Wind earned him an honorary award at the 1940 Oscars that cited his “use of color for the enhancement of dramatic mood.”

Alice in Wonderland 1933: Gary Cooper as the Knight who can’t stay astride his horse and who ‘invented a new pudding during the meat course’ of a meal. Alice (Charlotte Henry) finds a Queen’s crown and begins her tutoring in Queenhood. Concludes with the surreal banquet scene in which both the Leg of Mutton (played by Jack Duffy) and the Plum Pudding (George Ovey) address Alice before she returns home through the Looking Glass at movie’s end. A wondrous 10:20 segment of the film here.But he was also a gifted director in his own right, with a particular interest in the fantastic. His sparse but consistently inventive body of work includes Things to Come, the 1936 British production that was among the first post-apocalyptic science-fiction epics, and the nightmarish Invaders From Mars (1953), in which a young boy discovers that his parents are actually zombies controlled by a Martian spaceship buried in a sandpit near his suburban home.

Alice bears a thematic as well as stylistic resemblance to Invaders: both use spatially distorting techniques inherited from German Expressionism to view a cold, grotesque and foreboding adult world through the eyes of a child. And many of the innovative special effects in Alice—particularly, the “drink me”/“eat me” scene in which Alice (Charlotte Henry) grows and shrinks—seem to have been based on Menzies’s work in a series of short experimental films he produced in the early 1930s. (These films, including a movie interpretation of Paul Dukas’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice that clearly influenced Disney’s version in Fantasia, were recently released in a public domain collection from Alpha Video, The Fantastic World of William Cameron Menzies, $7.98, not rated).

Alice in Wonderland 1933: Alice encounters the Cheshire Cat, played by Richard Arlen.The treatment of the Cheshire Cat—always a defining moment in an Alice adaptation—is the apparent result of an ingenious combination of an actor in costume (Richard Arlen, recognizable only by his voice), an in-camera dissolve and phosphorescent makeup that leaves the “grin without a cat” not just hanging in space, but glowing eerily.

As dazzling as today’s digital effects can be (and Mr. Burton’s Cheshire Cat is sure to be memorable), we remain all too aware of how they are accomplished (computers!) for them to possess the seductive sense of mystification that Menzies and McLeod achieve here, using practical techniques derived from Victorian stage magic.

Menzies’s hand seems evident in almost every frame of Alice in Wonderland, yet his only credit on the film is as the co-author, with Joseph L. Mankiewicz, of the screenplay. In those days credits were not union mandated, and it is likely that Menzies, on loan from Fox, would have played down his role in the production so as not to offend his home studio. (According to the AFI Catalog, a Hollywood Reporter item from 1933 stated that Menzies was “loaned by Fox to co-direct the ‘trick sequences,’ ” and an article in The Times from October 1933 notes that “Mr. Menzies made careful scale drawings of each scene in the proposed picture, while Mr. McLeod prepared footnotes showing how Mr. Menzies’s pictorial conceptions could be photographed.”)

But Menzies might also have relished his role as an authorial eminence grise, exercising his creative power in indirect, elusive ways. It was a part he would play in any number of pictures, including Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe, Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent and King Vidor’s Duel In the Sun. A bit of a Cheshire Cat himself, Menzies fades away, leaving movies as distinctive and mysterious as this Alice behind.

***

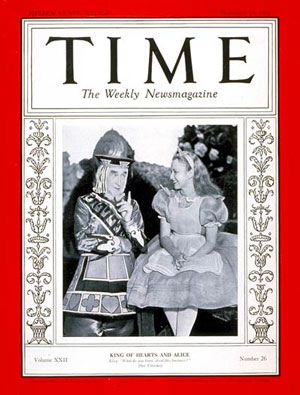

On December 25, 1933, TIME Magazine thought enough of McLeod’s Alice to make it the cover story for that week’s issue (http://www.time.com/time/covers/0,16641,19331225,00.html):It took Paramount 56 days to wrap up Lewis Carroll's masterpiece of nonsense and deliver it to U. S. cinema audiences for Christmas. As a prize package for the holidays the picture presented great problems to match great possibilities. To begin with, Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass had to be telescoped into one script. A cast of Big Names had to be assembled for publicity purposes and yet a Nobody had to play Alice. Artist John Tenniel's familiar characters had to be imitated if not exactly copied. And finally the screen production had to stand comparison with Eva Le Gallienne's excellent stage adaptation for her Civic Repertory Theatre. When Alice in Wonderland was released this week simultaneously in 120 cities throughout the land. Paramount could well feel that it had done its level best to make Christmas bright and merry for millions of youngsters.

Who was to play Alice was Paramount's Problem No. 1. Charles Laughton, not altogether facetiously, suggested that Jean Harlow would make an ideal Carroll heroine. Paramount settled the matter by means of a '"contest" in which some 7,000 would-be Alices were considered. After a minimum of hemming and hawing the prize role was given to a pretty round-faced 17-year-old girl from Brooklyn, N. Y. named Charlotte Henry. The direction of the picture was assigned to Norman McLeod (Horsefeathers, If I Had a Million) and real actors were engaged for all parts except those of the Walrus, the Carpenter and the Oysters. Two days after Miss Henry got her contract, the picture started in the Victorian drawing room where Alice is lolling in an embroidered armchair and chatting to her cat about the enchanted room which she is sure exists on the other side of the fireplace mirror. When her governess tiptoes out of the room, Alice climbs up on the mantelpiece, presses her snubnose hard against the looking glass and suddenly finds that she has walked through it. She floats softly to the floor of the other room. There she has a conversation with her Uncle Gilbert (Leon Errol) whose portrait naturally shows only his rear and the patch on the seat of his trousers. She argues politely with the Clock (Colin Kenny). She investigates goings-on among the members of her father's chess set, who are squealing on the hearthstone because the White Queen's (Louise Fazenda) pawn has climbed dangerously to a tabletop. Alice straightens out this difficulty and sets off to examine the other rooms of the looking-glass house. A curious wind whisks her down the stairs, through the front door, down the garden path. There she picks up the White Rabbit (Skeets Gallagher) on— his way to the" party. When she has followed the Rabbit down his hole, the first person Alice meets, swimming about in a puddle of the tears which she has wept before eating the cake which reduces her to appropriate Wonderland size, is a Mouse (Raymond Hattonj who dislikes her instantly. Next she encounters the Dodo; the supercilious Caterpillar (Ned Sparks); the Frog-Foot-man (Sterling Holloway); the hideous Duchess (Alison Skipworth) maltreating an infant; the Cheshire Cat (Richard Arlen).

As Alice wanders on, she meets still more Wonderland characters. The Queen of Hearts (May Robson) orders off with her head. The King of Hearts (Alec Fran cis) countermands the order. At the tea-party of the Mad Hatter (Edward E. Horton), Alice is duly depressed when he and the March Hare (Charles Ruggles) try to put the Dormouse (Jackie Searl) into the teapot. The Gryphon (William Austin) introduces her to the Mock Turtle (Gary Grant) who sings for her his gloomy accolade to soup. When preposterous, pot bellied Tweedledee (Roscoe Karns) be gins to recite his poem, Tweedledum (Jack Oakie) opens the door of a small contraption resembling a birdhouse to exhibit Walrus, Carpenter and Oysters capering sadly in a Walt Disney cartoon. She meets the lugubrious White Knight (onetime Cowboy Actor Gary Cooper) who, between falls from his horse to which a stepladder is attached, explains to her about his invention for getting over fences. When Humpty Dumpty (W. C. Fields) falls off his wall, the calm cavalry of the White King (Ford Sterling) arrives to re assemble him. Finally, Alice arrives at a wild dinner party, where the Leg of Mutton (Jack Duffy) sneers at her, the Plum Pudding (George Ovey) objects to being sliced, and where, in a sudden state of nightmare alarm, the White Queen screams "Take care, something's going to happen!'' Alice, squirming in her chair at the table, suddenly finds herself back in the embroidered chair in her own drawing room with her own placid cat purring in her lap. Partly because his gnarled, poetic non sense refreshes a realistic age and partly because it contains the key to a character that would now be a wonderland for any well-informed psychiatrist, Lewis Carroll has become the idol of a cult. What Carroll cultists will think of the cinema version of Alice in Wonderland is even more difficult to predict than the reactions of normal U. S. cinema audiences. One thing in the picture which neither class is likely to object to and which children will probably like best of all is Alice herself. In a script sequence the King of Hearts asks Alice: "What do you know about this business?" If the King were speaking of the cinema business, Charlotte Henry would have been obliged to answer him truthfully: "Not much." That fact principally explains the charm of her performance.

Charlotte Virginia Henry was born in Brooklyn, brought up in Manhattan. When she was 9, she decided she wanted to be an actress. At 14, she contrived to get a part in the Manhattan production of Courage. The next year she persuaded her mother, separated from her father who is a surgical supplies agent, to take her to Hollywood. There she finished her schooling at the Professional Children's School, performed as Mary Jane in Paramount's Huckleberry Finn. For the next two years, she had few jobs. She was playing in a Pasadena Community theatre production of Growing Pains when another girl in the cast suggested that she apply to Paramount for the role of Alice. Only cynics who believe that nothing in the cinema industry is conducted honestly suppose that the fact that Charlotte Henry had worked for Paramount before was incontrovertible evidence that the result of the contest was prearranged. Says Charlotte Henry: "Once I had a very bad toothache. The dentist said it would have to come out. I had a sinking feeling and I began to hurt all over and I cried. That's just what happened when they told me I was going to play Alice."

As soon as she was selected for the part, she began to be badgered by writers for U. S., British, German, French, Italian, South American and Japanese cinemagazines. They discovered that she is five feet tall with blue eyes and flaxen hair worn down her back and tied with a ribbon; that she dislikes spinach, eats ham three times a day by preference; owns a Pekinese dog named Puddles; thinks boys talk too much; admires Rudy Vallee; considers rain lucky; that her diversions are scribbling on blackboards, reading detective stories, swimming, golf; that her nickname is Chotsie; that she has no favorite cinema star; that the first thing she does when she enters a room is to switch on the radio. More significant than such personal trivia is Charlotte Henry's childish refusal to be impressed by the public curiosity which elicited them. Said she: "It's the part of Alice, not me, that's causing all the attention."

During the two months that Alice in Wonderland was in production, she worked from eight to 16 hours per day with no days off, wore out 12 costumes, got hit by pots and plates in a scene with the violent Duchess, hurt her ankle jumping off the mantlepiece. Started two weeks late, the picture was finished two days ahead of schedule. Charlotte Henry and her mother, who stayed away from the lot during the filming lest she be considered officious, were released from studio routine for a 30-day tour of the 20 largest cities where Alice is to be shown. Last week, the Henrys visited Kansas City, Washington, Manhattan, Boston, Philadelphia. In Philadelphia, Charlotte was disappointed because she just missed a touring Civic Repertory performance of Alice in Wonderland. In Washington she lunched with House Speaker and Mrs. Henry T. Rainey.

Among the qualities that make Alice unique as a personage in fiction is the bland and dreamy indifference with which she comports herself in extraordinary circumstances. Though her small histrionic training has helped, what makes Charlotte Henry's performance as Alice satisfactory is the fact that she possesses much the same quality in everyday life. When she arrived in Hollywood three years ago, she was disappointed. The sea was 27 miles away. Streets which she had expected to see thronged with celebrities resembled the streets of any other city. As she prepared to leave for Atlanta, Charlotte Henry had small time in Manhattan last week to wonder whether the glum prophecy of the White Queen would presently come true. Whether, as she herself hopes, she will presently become a cinemactress celebrated in her own right or whether her career will parallel that of Betty Bronson, who five years ago made a success as Peter Pan and now thankfully plays bit parts, will depend less on Alice than on Charlotte Henry's subsequent performances. Her next, as planned at present, will be Lovey Mary in Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: [email protected]

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024