1951: THE DISNEY VERSION, AND ITS LOST CHAPTER

(Or, Lew Bunin Lives!)Alice In Wonderland looms large in Walt Disney’s legend. His pre-Mickey Mouse, studio launching series of “Alice” Laugh-O-Gram shorts (see the Alice Errata section in this issue to view the first of these, “Alice’s Wonderland”) was inspired by Lewis Carroll’s stories. When he had the idea to make feature-length animated films, Alice was at the top of his to-do list, even ahead of what became his, and cinema’s, first feature-length animated movie, Snow White and The Seven Dwarfs. Intending to mix live action with animation in his Alice movie, Disney went so far in 1933 as to do a screen test with Mary Pickford as Alice. Paramount’s Alice In Wonderland, released that year, had the added effect of persuading the Disney company to postpone its planned Alice film. In the late ‘30s, Walt made another run at Alice, but with the economy crunched by World War II, and productions of Pinocchio, Bambi and Fantasia already in progress, Alice was once again consigned to the back burner.

In 1945 Walt tried to move ahead on a live action/animation version of Alice, with Ginger Rogers in the title role, but this too was shelved; only a year later, though, an all-animated Disney version was storyboarded, its look heavily reliant on the classic illustrations Sir John Tenniel provided for the original edition of Lewis Carroll’s book. Unenthused, Walt rejected this version as well as another proposal for a live action/animated film starring Luanna Patten (who would appear in Disney’s Song Of the South and So Dear To My Heart).

The complete Unbirthday Party scene from Walt Disney’s Alice In Wonderland (1951). The Mad Hatter is voiced by the incomparable Ed Wynn.Here we pick up the story from Wikipedia:

In the late 1940s, work resumed on an all-animated Alice with a focus on comedy, music and spectacle as opposed to rigid fidelity to the books, and finally, in 1951, Walt Disney released a feature-length version of Alice in Wonderland to theaters, eighteen years after first discussing ideas for the project and almost thirty years after making his first Alice comedy. Disney's final version of Alice in Wonderland followed in the traditions of his feature films like Fantasia and The Three Caballeros in that Walt Disney intended for the visuals and the music to be the chief source of entertainment, as opposed to a tightly-constructed narrative like Snow White or Cinderella. Instead of trying to produce an animated "staged reading" of Carroll's books, Disney chose to focus on their whimsy and fantasy, using Carroll's prose as a beginning, not as an end unto itself.Another choice was decided upon for the look of the film. Rather than faithfully reproducing the famous illustrations of Sir John Tenniel, a more streamlined and less complicated approach was used for the design of the main characters. Background artist Mary Blair took a Modernist approach to her design of Wonderland, creating a world that was recognizable, and yet was decidedly "unreal." Indeed, Blair's bold use of color is one of the films most notable features.

Finally, in an effort to retain some of Carroll's imaginative verses and poems, Disney commissioned top songwriters to compose songs built around them for use in the film. A record number of potential songs were written for the film, based on Carroll's verses—over 30—and many of them found a way into the film, if only for a few brief moments. Alice in Wonderland would boast the greatest number of songs included in any Disney film, but because some of them last for mere seconds (like "How Do You Do and Shake Hands," "We'll Smoke the Monster Out," "Twas Brillig," "The Caucus Race," and others), this fact is frequently overlooked. The original song that Alice was to sing in the beginning was titled "Beyond the Laughing Sky.” The song, like so many other dropped songs, was not used by the producers. However, the composition was kept and the lyrics were changed. It later became the title song for Peter Pan (which was in production at the same time), "The Second Star to the Right.”

The title song, composed by Sammy Fain, was later adopted by jazz pianist Bill Evans and featured on his Sunday at the Village Vanguard.

(Italicized portions from Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice_in_Wonderland_%281951_film%29)The Lost Chapter

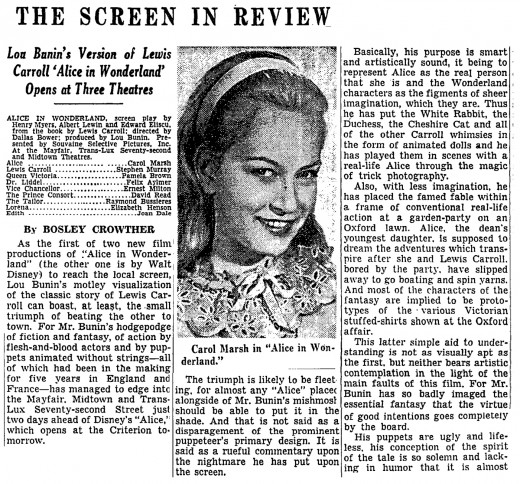

A scene from Lou Bunin’s Alice In Wonderland live action/animation feature, starring Carol Marsh as Alice; 1949, released 1951.

Disney’s Alice In Wonderland drew from both Alice's Adventures In Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass, mixing episodes of both into a single narrative without regard, really, for a story arc, as it were. Upon release the Disney version was competing with another Alice In Wonderland on film—one created in 1949 by Lou Bunin, a politically active, left leaning puppeteer and pioneer of stop-motion animation (he combined his politics and his affinity for stop-motion animation in a celebrated 1943 political satire, Bury the Axis) whose Alice movie starred Carol Marsh as a live-action heroine and was animated by former Disney artist Art Babbitt. A lawsuit brought by Disney against Bunin prevented the latter’s film from being widely distributed in the U.S., and it was banned in Britain over concerns that Bunin’s Queen of Hearts was in fact an unflattering portrayal of Queen Victoria. In his July 30, 1951 review of Disney’s Alice in The New York Times, critic Bosley Crowther made note of Bunin’s version arriving in the city at the same time, but declared: “Mr. Disney's unreined improvisation upon the fine fantasies of Mr. Carroll must be declared the better by a margin of a couple of years.”

Crowther concluded: “But if you are not too particular about the images of Carroll and Tenniel, if you are high on Disney whimsey and if you'll take a somewhat slow, uneven pace, you should find this picture entertaining. Especially should it be for the kids, who are not so demanding of fidelity as are their moms and dads. A few of the episodes are dandy, such as the mad tea party and the caucus race; the music is tuneful and sugary and the color is excellent. Watching this picture is something like nibbling those wafers that Alice eats.”

The New York Times account of the Disney-Bunin lawsuit:

And Bosley Crowther’s New York Times review of Lew Bunin’s Alice:

A near 10-minute clip from Lou Bunin’s live action/animation version of Alice in Wonderland, produced in 1949, released in 1951 after Bunin won a lawsuit in which Disney attempted to quash release of his film in the United States. Both a master puppeteer and a pioneer of stop-motion animation, Bunin’s artistry was in peak form on Alice. Bunin’s animator was Art Babbitt, formerly of the Disney studio.

Lou Bunin’s Alice in Wonderland is available at www.amazon.com. Caveat emptor: the DVD is, as one reviewer notes below, “marred by photochemical decay of the print” and by shoddy remastering. But it’s the only version extant of Bunin’s delightful, sadly overlooked Alice.

Amazon.com review by R. Gorey ‘Behemoth’

I had the privilege of meeting and studying with Lou Bunin while at college. He was very proud of this film, and rueful regarding the circumstances which kept it from wider release. In our class, Bunin ran a beautiful 16mm print of his "Alice" that was superior to the copy on this DVD. How unfortunate that the original colors and crispness are lost. This DVD version has no chapter stops, special features, interviews, or commentary. Too bad; it's a film that could have used them. For animators and fans of stop motion, I'd say take a look, and at least the price is lower than the usual. But even for devotees of the "Alice" stories, the film itself can be dense and off-putting, in that it faithfully recreates the arch cynicism and curious aloofness of the original story. This film cries out for a loving restoration: sadly, this isn't it, but it may be the only way to see Bunin's "Alice" for the time being. Bunin was a wonderful, warm, and talented man, and this feature is, to many, his most lasting legacy. If viewers can see beyond the limitations of the poor transfer, they may come away impressed with the artistry and cleverness of the movie's dream-like design.Amazon.com review by J. Knott

It's great to have this adaptation of Carroll's story on DVD, but the presentation is quite shoddy.I saw this film at the National Film Theatre in London, and the audience was warned then that the best available print was in poor shape. The particular brand of film stock it was shot on was unstable, and the colour fidelity of the print shown was inconsistent. The film also suffered from some sort of chemical decay down one side of the image. These faults have been faithfully reproduced on this DVD edition.

Sadly, the DVD transfer has only compounded these problems. It's been mastered from an analogue tape source, and quite a low quality one at that (possibly U-Matic). The tracking of the playback isn't stable, and the top third of the picture suffers from chroma problems. On computer monitors, or other displays with no overscan, you can see head switching artifacts at the bottom of the screen.

In summary: this a wonderful adaptation of the story, marred by photochemical decay of the print, and further blighted by shoddy video mastering.

The ‘Very Good Advice’ scene, Alice In Wonderland, Disney, 1951

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Disney’s two-disc Special Un-Anniversary Edition DVD of Alice In Wonderland is available at www.amazon.com

Disney’s two-disc Special Un-Anniversary Edition DVD of Alice In Wonderland is available at www.amazon.com