Getting To Lonesome, On’ry and Mean

The Annotated Waylon: Six new Waylon Jennings reissues from his early years tell a story of an artist fighting for his visionBy David McGee

It may be for some that Waylon Jennings is so identified with the Outlaw movement in country music that the pre-Outlaw, establishment Waylon (establishment in sound only; his temperament was always that of a renegade) is too often disregarded. Waylon himself is partly to blame for that, but only owing to his attempts to explain why he came to bristle at the constraints of Music Row’s hit making machinery as he attempted to assert his individual voice as an artist. He would be the first to tell you, though, that the machinery suited some more compliant artists well indeed but ultimately worked against those with a vision, and not least of all, with a mongrel sound stitched together from influences outside traditional country—such as, in his case, hard charging rock ‘n’ roll; he was, after all and very briefly, Buddy Holly’s bass player and for longer than that his fellow Texan Holly’s confidante and student.

Thanks both to his autobiography, Waylon, written with Lenny Kaye, as well as to informed liner notes accompanying various reissues preceding these essential new Collectors’ Choice two-fer sets encompassing six of the 14 Waylon albums recorded between 1966 and 1970, the early details of the Nashville Rebel’s career are well known: started out as a disc jockey in Texas; encouraged by Holly to become an artist in his own right; emotionally devastated after Holly’s death; relocated to Phoenix and became a local superstar drawing turn-away crowds to his weekly shows at JD’s club; signed to the fledgling A&M label by owners Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss, where he cut some interesting, stylistically diverse singles; befriended by Bobby Bare, who had a hit with one of Waylon’s early self-penned songs and championed him to Chet Akins at RCA, who signed Jennings and was his first producer; struggling financially and strung out on a variety of pills and “roaring” all the way. Oh, and he married four women and divorced three of them before the ‘60s were over, finally doing right by the last of his brides, Jessi Colter (the former Mrs. Duane Eddy), when they tied the knot at a wedding mill in Las Vegas, with the future Mrs. Jennings laughing hysterically through the entire ceremony, recovering her composure only long enough to gasp, “I do!” at the end.

Then there’s the Waylon of these early RCA albums. Outside the studio, working the road ceaselessly, he was as pill-crazed and financially strapped as ever, driving himself beyond the point of exhaustion (and being ripped off at about every level of the business, from the accountants at his publishing house to promoters, club owners and everyone in between) trying to build an audience and stay solvent all at once. Inside the studio, despite his frustrations with the system and certain producers not named Chet Atkins, he was disciplined, focused and quite often incredibly powerful in making his voice heard. That muscular, tuneful baritone was a tad bit airier than in his later years, of course, but it carried tremendous emotional conviction; in listening to any one of these albums straight through, or sampling various tracks out of chronological order, a listener is struck by the authority of his singing, how inseparable its personality was from that of the singer's, and how deeply he believed in what he was saying, whether bringing one of his own songs to life, rooting around in one by his buddy Harlan Howard, or being one of the first mainstream country artists to find common ground with Lennon-McCartney songs, a full decade-plus ahead of a New Traditionalist movement that dutifully worshipped at the altar of Rubber Soul.

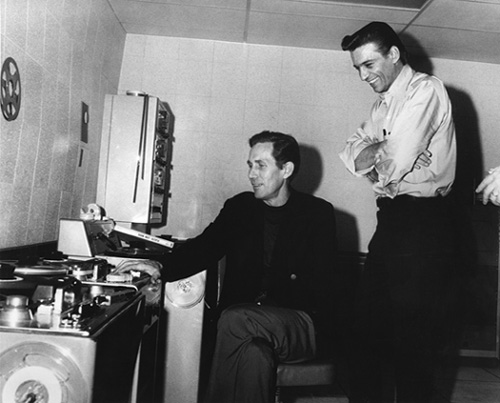

Chet Atkins and his new artist, Waylon Jennings, in the control room at RCA’s Studio B (Photo: Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum)I was starting to realize it wasn’t the individual producer that made the difference.

Nashville had a definite, set formula for what a country record should sound like. There’s more than one kind of country music though—a wide range that takes in everything from bluegrass to western swing. Their country was smooth and pop, one road that led to a Nashville Sound. Well, I couldn’t do that. I didn’t want to do that.

I had an energy, and it made them afraid. In response, they tried to control me, make me a cog in their machine, and it didn’t stop with record production. Everybody got it on it: the marketing department, the promoters, the talent bookers. “I didn’t like his last album; he had some songs on there that sounded like rock and roll to me.” Maybe there was a heavier bottom, a rock and roll beat driving a country song, but if there’s no edge in the music, there’s no edge in me. (from Waylon: An Autobiography, by Waylon Jennings with Lenny Kaye, Warner Books 1996).

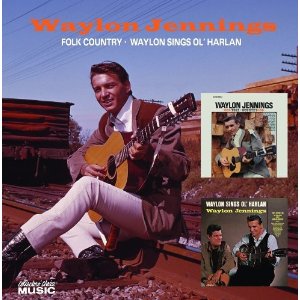

Jennings’s relationship to his producers forms, arguably, the main storyline emerging from these albums. Three are represented here: Chet Akins, primarily; Danny Davis (Waylon); and Lee Hazlewood (Singer Of Sad Songs). (Ronnie Light also produced Jennings during this timeframe, but only Atkins, Davis and Hazlewood productions populate this batch of reissues.) Company man Atkins is held in high esteem by most every artist he ever worked with, both for his empathy in the control room and his basic decency as a man, and Jennings was no exception. Folk-Country, Waylon Sings Ol’ Harlan, Love Of the Common People and Hangin’ On are all Atkins productions, and all bear the trademark of the Nashville Sound, minus strings, meaning a pop sheen via Floyd Cramer’s or Hargus “Pig” Robbins’s piano and honey-voiced background singers. Entrenched in the Nashville machinery as he was—in fact, he had helped build it—Atkins butted heads with Jennings right off the bat in his insistence on using the A team session players over Waylon’s road band.

Chet wanted me to be myself, but he wanted me to be myself with musicians he knew were great, that he’d been relying on. Chet had his comfort zone: a drummer that never wavered, a piano solo that tickled the same ivories, a smooth background vocal from the Jordanaires or the Browns or the Anita Kerr Singers. -–from Waylon: An Autobiography

To Waylon’s credit, though, he found his own comfort zone on the Atkins-produced albums; and to both men’s credit, and to the good of the music, they forged a fruitful working relationship within the system. On his RCA debut, March 1966’s Folk-Country, Jennings put the “folk” into his music by introducing Nashville recording to the 12-string guitar in his own lilting love song, “Cindy of New Orleans.” Over Charlie McCoy’s tenderly crying harmonica and a thumping rhythm that sounds inspired by the Marty Robbins chart topping version of Gordon Lightfoot’s “Ribbon of Darkness” from a year earlier, Waylon’s sensitive, subdued vocal on “Look Into My Teardrops” (a Harlan Howard co-write; in fact, five of the songs on Waylon’s RCA debut were Howard copyrights) elevates the song to a grander plane of heartache, especially his subtle but bitter reading of the abrupt kissoff at song’s end: “Aren’t you proud of what you’ve done?” And although it was his fourth RCA album release, March 1967’s Waylon Sings Ol’ Harlan had been recorded before Folk-Country, and featured some big Harlan hits (“Heartaches By the Number,” two co-writes with Buck Owens on “Tiger By the Tail” and “Foolin’ Around”) and some that were destined for classic status, such as “Busted.” Working with a basic band and few sonic embellishments, Jennings puts his signature on the tunestack in a profound way: he attacks “She Called Me Baby” with authority, digging down into the crunching arrangement for a bluesy delivery that demonstrated how rich his vocals could be, in a performance invigorated by his upper register swoops between the moaning verses; his “Busted,” in contrast to the treatment his buddy Johnny Cash would give it later, skips along at an easygoing pace, with Waylon’s carefree vocal underscoring a telling contrast between his character and the song’s desperate lyric; his “Heartaches By the Number” is nothing less than an example of straight-ahead, uptempo country vocalizing over a twangy arrangement, a recording bound for the mainstream.

Waylon Jennings, ‘Mental Revenge,’ a #12 country single, produced by Chet Atkins for the Jewels albumChet cut the best records of my early years. He may have told me once or twice to straighten up, and looked with disapproval on my drug use, but like Don Gibson, I think he thought of me as a good renegade.

He encouraged my strange harmony singing, even if I would combine tenor and baritone parts in the same overdubbed voice, with some odd notes besides. He picked up on the fact that I emphasized the 1 and 3 beat of the 4/4 measure. Most musicians will kick the 2 and 4, but the 1 and 3 is the way the public thinks if you get them clapping in an auditorium. And he liked that I didn’t sound like anyone else when I sang. He always says he can tell in two notes if it’s me singing. …

We had some great time together, and we cut some wonderful songs. On February 15, 1967, nearing the end of surviving my first year in Nashville, we did a John Hurley/Ronnie Wilkins composition called “Love of the Common People.” It had it all—the horn stabs that I loved so much, an insistent piano figure that lodged in your brain, and four (count ‘em) key modulations upward, so that the song never stopped getting you higher. The lyrics were especially meaningful, for a poor country boy who had worked his way up from “a dream you could cling to” to a spot in the working world of country music.

A song is where it starts. Chet believed that too. If you don’t have a song, you don’t have anything. (from Waylon: An Autobiography)

Released in August 1969—the summer of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band—Love of the Common People—the song (whose writers, Hurley and Wilkins, also wrote “Son of a Preacher Man”) and the album—had ample supplies of all those elements Waylon rhapsodized about in his autobiography, but the sturdy, marching beat of the title song, its ever-ascending key modulations, the proud horns and triumphant chorus were more than matched by a determined reading of the lyrics. But it became a bigger song than Waylon ever imagined, no matter how much he identified with its lyrics. As he learned on a tour stop in Flagstaff, Arizona, after the album’s release, a local station had been playing the song, and at one point had to cue it up six times in a row to satisfy its callers, almost all of whom were Navajo Indians. The tribe had adopted “Love of the Common People” as its “national anthem,” so strong was their feeling for its lyrics, or as Waylon put it in his autobiography: “’Livin’ on dreams ain’t easy.’ ‘Family pride.’ ‘Faith is your foundation.’ ‘The Love of the Common People,’ if you think of ‘Common’ as shared heritage, hopes, a tribe to cling to, and a warm conversation. Strong where you belong.”

The album echoes with populist sentiments beyond its title track: the prisoner aching for freedom in the dark, doom-laden “The Road,” with its yearning harmonica and eerie soundscape; the return of the 12-string guitar in the Spanish-tinged atmosphere of the graceful ballad, “Money Cannot Make the Man,” which posits character as the quality an acquisitive woman overlooks in her suitors. More than that theme, however, Love of the Common People is an intense examination of various states of love, or lack thereof, featuring Waylon’s most soulful recorded vocals to this time. There isn’t a single song on which he’s coasting, or sounding as if he’s not fully immersed in the storyline, sometimes painfully so—as in the somber, even funereal musings on loneliness that “cuts me and tortures my soul,” in the hymn-like “I Tremble For You”; as in the measured introspection of another moody, Spanish flavored ballad, the Marty Robbins-like “Taos, New Mexico,” which recounts a broken-hearted man’s quest for spiritual healing and new love in a new town with a legend for providing exactly what he’s looking for; as in the mix of suppressed rage and self-pity he directs at his straying woman, who’s stepping out on an injured Vietnam Vet in, yes, Mel Tillis’s “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town,” the first recording of the song that became a smash hit for Kenny Rogers & the First Edition (and lamentably sustained Rogers’s career when it was at low ebb). The heartbreak theme even extended to the second Beatles tune Waylon covered, “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” an interesting version that blends pop and country flavors, and finds Waylon employing much the same halting, dramatic phrasing he used on his first Beatles cover, “Norwegian Wood,” which appeared on the 1966 soundtrack album accompanying his movie debut, Nashville Rebel.

If Waylon’s final Chet Atkins-produced album of this reissue collection, February 1968’s Hangin’ On, has the feel of a singles collection, that may well have been the intention. Atkins was expert at cutting hits, but Waylon had yet to achieve any major breakthroughs in that department. Of the dozen songs here, only two bear the Jennings copyright (the uptempo mean woman blues, “Julie,” and another bluesy ode to an unfaithful female, “Right Before My Eyes,” a midtempo meditation with twanging guitar and a pop chorus behind Waylon, was a co-write with his buddy Don Bowman along with Jackson King); other contributions came from writers with a track record of single hits: Bobby Bare (a Spanish-tinged kissoff number, “Woman, Don’t You Ever Laugh At Me,” sung with an interesting blend of abiding heartache and confrontational severity); John Hartford (a terrific, laid-back and string-enhanced version of “Gentle On My Mind” closer to Hartford’s own reserved, folkish version than to Glen Campbell’s uptown country smash hit released the same year as Waylon's); Roger Miller (a straightforward, heartbreaking country ballad, “Lock, Stock and Teardrops,” that had already been a minor hit for Miller, but given a torchy treatment here complete with a weird, whining horn section, moaning pop chorus and Waylon soaring into his keening upper register to lay on the enduring ache he’s singing of). Back at JD’s in Arizona, Waylon had made Roy Orbinson’s songs part of his legend, seeing as how he could actually sing them as Orbison did, high notes and all, and he had earlier in his career cut a version of “Crying” that paled considerably next to the Big O’s and left much to be desired in terms of Waylon matching Orbison’s big finish. Righting himself on Hangin’ On, he assayed a minor but typically schizoid Orbison scenario of neuroses and epic loss, “The Crowd,” each verse building in intensity, and Waylon’s trembling vocal with it, until he explodes into the stratosphere vocally with 15 seconds left, in a tour de force flight of breathtaking power and feeling. But it fell to Ol’ Harlan (as in Harlan Howard) to make Waylon’s day, or album, as it were. His sprightly, catchy, uptempo shuffle, “Looking At a Heart That Needs a Home,” about a footloose wanderer in search of a woman “who wants a gentle man and accepts me as I am,” was completely sold by Waylon’s eager vocal, being that he was on intimate terms with the kind of fellow Howard so accurately portrayed in a couple of verses and poignant choruses. It wasn’t the hit Waylon and Chet were looking for, but another Howard song was.

Gordon Lightfoot’s “(That’s What You Get) For Lovin’ Me” was Waylon’s first Top 10 country single, off his second album, Leavin’ Town, released October 1966 (not part of the new reissue series)In the fall of ’67 Waylon made it into the country Top 10—peaking at #8—with Harlan’s tearjerking ballad, “The Chokin’ Kind.” It begins with a repeating 12-string triplet riff lifted from Peter and Gordon’s “I Go To Pieces” (which was written by Del Shannon) before Waylon enters, singing in a halting, even fearful tone, lamenting a woman’s suffocating love for him and trying to explain why he has to move on, but not before offering the sage advice to accept people for who they are and, in a variation on the old blues refrain, “if you don’t like the peaches/walk on by the tree.” A beautifully crafted mini-drama, “The Chokin’ Kind” is one of the most subtle singles in the Waylon oeuvre, with his measured vocal of a piece with the low-key arrangement and the subdued crooning of the Anita Kerr Singers behind him, almost like a whisper echoing his soul’s torment.

The making of “The Chokin’ Kind” became an object lesson in the producer’s art and authority for Waylon. The first version was cut shortly after Howard had written the song and played his vocal-and-guitar demo for Waylon. Jerry Reed, who was booked for the session, got excited about it and, with Harlan, rolled tape without Atkins present; when the session was done, the song had been transformed into something Waylon couldn’t abide, but he thought he was stuck with it as the finished track. “They had just taken the song away from me,” Waylon wrote in his autobiography. “I was so depressed. I loved that song, because it was really where I was at in my life at that time.”

The tearjerking Harlan Howard ballad, ‘The Chokin’ Kind,’ was a #8 country single for Waylon in the fall of ’67 and an object lesson in the producer’s art and authority for Waylon. Waylon takes credit for introducing the 12-string guitar to Nashville recording, and he’s playing one here, notably on the opening riff, lifted from Peter & Gordon’s Del Shannon-penned hit, ‘I Go To Pieces.’ The song was included on Waylon’s 1968 album, Hangin’ On.Having been alerted that Waylon was drowning his sorrows in some beer joint on Lower Broadway, Atkin’s dutiful secretary, Mary, tracked him down and asked what was going on. After hearing what had happened in the studio, along with Waylon’s lament that “they just did it and it’s done with and I didn’t even get a chance to make my feelings known. They ruined my song,” Mary called Chet, who reacted immediately.

He said, “Don’t ever leave the studio like that again. I will stay all night long with you, but don’t let that happen. You come tell me that it’s not right.” He knew what music was meant to be, and how much I cared, no matter what shape I was in.

The next morning I came back to the studio; we were scheduled for another session. “What are we going to do?” the band asked.

“’The Chokin’ Kind.’”

“We did that yesterday.”

“No, you did that yesterday,” I said. “I’m doing it today.” (from Waylon: An Autobiography)

By 1969 Atkins, the only producer Waylon had worked with since coming to Nashville, was reducing his producer’s role at RCA in favor of performing again. Danny Davis, founder and leader of the Nashville Brass, and staunch defender and practitioner of the pop-oriented Nashville Sound, was Atkins’s designated successor behind the board. It was not one of Chet’s legendary good calls, as Davis’s aesthetic embraced everything Waylon loathed about the Music Row machinery. That the Davis-produced Waylon (January 1970) came out as well as it did says more about the titular artist’s professionalism than it does about the producer’s acumen, but it’s also something of the last straw for Waylon the company man. He had played the game as best he could to this point, sparring with Atkins at times but ultimately respecting his judgment and willingness to let the artist assert individuality within a commercial framework. Plus, despite coming to believe it wasn’t the individual producer that made the difference, Waylon also believed in the producer-artist collaboration.

“You need someone to help you do your listening and I love to see what people hear out of me. If it doesn’t work, I’ll tell them, but usually you shouldn’t have to even talk about it. The speakers will let you know when a song feels right.

I like to see what the producer has in mind; and between me not being able to do what I think I can, and trying to do what they want me to,a lot of times you come up with something that neither of you might have thought of in the first place. You have to be prepared to take advantage of the unexpectd.” (from Waylon: An Autobiography)

Enter Danny Davis, and Waylon’s thinking on this subject evolved, shall we say.

Danny didn’t care what I was about; in his eyes, the producer was there to control the artist. He did want the best for me, but that was a value judgment he wasn’t allowing me to make. “This guy could be the biggest star in the world,” he told Johnny Western, who wrote the liner notes for Waylon, released in January 1970, but he’s his own worst enemy.” That can never work. You have to trust the instincts of the artists you’re helping to record. I may not know that much about music, but I know what gets me. (from Waylon: An Autobiography)

Waylon’s account of the Waylon sessions is unsparing in its savaging of Davis’s approach. He would return the day after a session to find a song changed beyond recognition, or arrangements overdubbed without his permission; he rejected songs after Waylon had agreed to do them—“Abraham, Martin and John” being one such tune; Waylon liked to learn his parts on the spot and in the moment, whereas Davis wanted them written out; and, according to Waylon, Davis also poked fun at him as he was trying to work out chord changes he wanted to hear in a song. Even the musicians Davis hired rankled Jennings with their habit of playing pickup notes—upbeat notes played before the first measure’s downbeat—because “it’s like stompin’ your way into a song, announcing that you’re going to knock on the door before you actually do.” To get his point across, Waylon showed up for a session one day packing a .22 Magnum buntline pistol and threatened to blow off the fingers of “the first sonofabitch that hits a pickup note.” Turning to Davis, he took aim. “And Danny, I don’t want to hear any shit out of you.”

Waylon: An Autobiography offers an understated assessment of the producer-artist relationship following this outburst: “It was all over between us from then on.”

Despite his disdain for producer Danny Davis, Waylon turned in some fine performances on his 1970 album, Waylon. One of the best came on a dramatic rendering of Mickey Newberry’s unflinching account of a stoner’s complete disconnect from reality, ‘The Thirty Third of August,’ recorded in 1969, the same year Kris Kristofferson introduced his similarly-themed “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down’Nevertheless, and in many respects, Waylon is a fine album. It contains only one Waylon original—a bouncy tribute to his third wife, “Yellow Haired Woman,” with popping guitar interjections and a mildly stomping beat, but nothing in its happy ambience to suggest the conflicts Waylon was describing in his lyrics. Thus the oddest aspect ofthe album—Davis’s arrangements often sound at cross purposes with the gravity of the lyrics and the powerful feeling in Jennings’s voice. The pinched guitar sound, emulating a sitar, in “I May Never Pass This Way Again,” might have worked as an exotic flourish in a more folkish arrangement, as the Beatles had deployed it, but in a straightforward country ballad about a drifter leaving town and the “little girl” he’s been seeing there, it’s more distracting than mood enhancing. Similarly, the upbeat vocal chorus warbling behind Waylon in the breakup song, “Yes, Virginia,” is jarring, to the point of undermining the sorrow in the singer’s voice.

But when Davis stays out of the way, or has a surer hand on things, the results are compelling. The dark, doom-laden “Just Across the Way” (its recurring, circular guitar riff lifted from Jerry Reed’s “A Thing Called Love”) is a restrained folk-country beauty, the subdued arrangement heightening the drama throughout; the shimmering guitar, evocative, minimalist vibes and pop-country backing chorus give the tearjerking ballad, “Shutting Out the Light,” an appealing early ‘60s pop feel, with Waylon’s muscular but measured vocal adding the country element that gives the song its adult temperament; the Spanish-tinge of the solemn heartbreaker, “Where Love Has Died,” returns Waylon to Marty Robbins territory, where his deep, brooding vocal adds a rough-hewn texture in a pleasing contrast to the plaintive gut-string guitar stylings; Mickey Newberry’s unflinching account of a stoner’s complete disconnect from reality, “The Thirty Third of August,” has a keening, prominent bass line, stinging but almost subliminal guitar, a churchy organ humming throughout and a relentlessly abject ambiance that Waylon, who had some experience with the state of mind limned in Newberry’s lyrics, sang it as if he’d been exactly in the same place and in the exact condition outlined in the story. (The precise dates when each was recorded have not been verified, but Newberry’s song and Kris Kristofferson’s similarly themed, and far better known, “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down,” were both recorded in 1969 and bear striking similarities to each other.) Not the least of Waylon’s charms is a jubilant duet love song, “All of Me Belongs to You,” featuring Waylon singing of his unswerving devotion to his female counterpart, whose part is handled with aplomb and conviction by one of country’s great female vocalists, Anita Carter, June’s sister, who get a great assist from the exuberant, shuffling arrangement and a chattering guitar line that serves as the instrumental evocation of the couples’ blissful pairing. It’s a shame Waylon and Anita never recorded a duet album, because the energy and passion emanating from this performance is on a par with that of George and Tammy, or indeed, Johnny and June.

But Waylon was Waylon’s sayonara to the Nashville way of doing things when it came to making records. Its 11 songs were not cut as part of an organized, systematic effort to make a coherent album statement, but in fits and starts between 1967 and 1969, during breaks when Waylon was off the road. That’s the way it was done then, and continues to be the case today, but Jennings was bound and determined it not be his way. For his next album, Singer of Sad Songs (November 1970), he packed up and headed west, to Los Angeles, where he cut everything in three days. Danny Davis was nowhere near L.A.—Waylon hired Lee Hazlewood, then hot with his Nancy Sinatra productions and fresh off producing one of the first country-rock fusion projects with Gram Parsons and his International Submarine Band. The backing band included Randy Meisner, who had been a founding member of Poco and had played with Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band, the latter group also being the home of both Allen Kemp and Patrick Shanahan, who were recruited for the Jennings sessions (both went on to become founding members of the New Riders of the Purple Sage). Though it contains no Jennings originals, Singer of Sad Songs (its title song, by the way, was a carryover from the Waylon sessions, produced by the loathed Danny Davis) is a lean, sinewy production, with lots of acoustic guitar at its base, tasty, driving electric guitar, subtle rhythmic flourishes from the bass, and the discrete use of harmonica not as a typical feature of the soundscape, but when its atmospheric fills are logical and suitable for the song. The band gets it together beautifully on a rambunctious handling of George Jones’s “Ragged But Right,” as well as on a countrified treatment, complete with a backwoods fiddle solo, of “Honky Tonk Woman” (which could only pale next to the then-current original version, which happened to be one of the Stones’ greatest singles, the fact of which obviously didn’t deter Waylon from trying his hand at it). By contrast, the arrangement on Tim Hardin’s “If I Were a Carpenter” expands and contracts to let Waylon root around in the verses with bluesy brooding, then rising in the choruses to reflect a certain urgency of the moment on the singer’s part. There’s also a straightforward, down-the-line thumping country number by that most mainstream of hit song writers, Bill Anderson, “Must You Throw Dirty In My Face,” with some playful lyrics and a toe-tapping lyric minus any of the pop inflections (no pop choral group, no cheesy guitar parts) Davis would surely have burdened it with—and that cannot have been an accident. Even Hazlewood the artist gets in on the action, when Waylon covers a song his producer wrote and had recorded in 1968, the intriguing gentle rocker “She Comes Running,” an exemplary country-rock production featuring the basic band supplemented in the choruses by the fanciful, tumbling flurries of a harpsichord, which gives it a decidedly late ‘60s So-Cal flavor, a half continent away from Nashville. (Hazlewood does make an appearance on the album, coming in for a couple of rumbling verses on U. Utah Phillips’s “Rock, Salt and Nails,” a midtempo shuffle in which homicidal impulses are muted by the song’s altogether upbeat attitude. Curiously, neither Waylon nor Hazlewood seems ever to have gone on the record about their collaboration—Waylon’s autobiography skips from Waylon to his 1973 single, “This Time,” cut on his own terms. It was his first #1 single.

But there is a last word, of sorts, from Waylon. In 1972 his longtime drummer, Richie Albright, had returned from after leaving the group nearly three years earlier, after telling Waylon he was “wore out” from the rigors of the road. He arrived at a moment when Waylon, despondent over his lack of success on record and terminally frustrated with Nashville’s handling of him, was about wore out himself, and contemplating retirement as a performer. Albright insisted there was another way to do things, “and that is rock and roll.”

Why not? It made a lot of sense. I was mentally rockin’ and rollin’. It was an attitude as much as a music, and we were rock and roll in everything but our allegiance to country. Even then, there was a lot of rock in that. We were proud to be country, but that didn’t mean we had to be trapped by country music’s conventions, or the way artists were treated. Maybe if I stopped trying to fit in, and started saying “fuck it,” I was going to get a chance to do it my way. If it didn’t work out, I’d be the only one to blame.

But when Albright said “rock and roll,” he meant more than a musical style. He meant bigger recording budgets; he meant actually hiring people—“roadies”—to be responsible for their gear when touring, instead of the musicians themselves having to set up at each venue they played. A wholesale transformation of the business is what Richie Albright was suggesting.

Breaking free of RCA’s assembly line production style, Waylon’s 1973 single ‘This Time’ signaled his independence as an artist, and other artists would follow his lead. Jennings’ first #1 single, ‘This Time’ was the title track of his July 1974 album, produced by Jennings and Willie Nelson. Willie also contributed four songs to the album, all from his acclaimed country concept album, Phases and Stages, released that same year.With the help of a hard driving New York lawyer, Neil Reshen, Waylon renegotiated his RCA contract and set up his own WGJ (Waylong Goddamm Jennings) Productions. Now he could control every aspect of his recordings—from song selection to the musicians used on sessions to the where and when of actual production—and with a larger budget and royalty rate to boot. For two years, though, he fought with RCA over the label’s objections to him recording outside the RCA studios and using non-RCA engineers (in violation of the company’s pact with the engineers’ union). Upon topping the charts with “This Time,” Waylon broke the system’s back: other artists followed his lead and asserted their right to record in the studios of their choice, and to have more control of their music. Its monopoly over, RCA had to sell its fabled recording facility, where a wealth of crucial post-war music—and all of Waylon Jennings’ recordings—had come to life.

Waylon turned to Chet Atkins, who had brought him into the RCA fold in 1966 and had never stopped believing in him, even if the expected big hits had not materialized from their work together. Making an offer to buy Studio B, Waylon was informed it was going to be turned into a museum. As Chet lit a cigar, Waylon suggested the company should sell him Studio A instead.

Gentle and beatific, Chet smiled. “You’ve got the nerve of Hitler,” he told Waylon. “You’re the reason we’re having to sell it.”

The two friends laughed together at the irony of it all. And then Chet said no.

Waylon: An Autobiography by Waylon Jennings with Lenny Kaye is available at www.amazon.com

Folk Country/Waylon Sings Ol’ Harlan is available at www.amazon.com

Love Of the Common People/Hangin’ On is available at www.amazon.com

Waylon/Singer Of Sad Songs is available at www.amazon.comThis set of reissues is released by Collectors’ Choice Music.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024