The New Greatest Christmas Song

Why the Scottish carol ‘Christ Child’s Lullaby’ is poised to become a standard

By Christopher HillWithout any hard numbers to cite, instinct says that, at least since the 1981 release of George Winston's December, we must be living in one of the great ages of Christmas music, in quantity if not always quality. Each holiday season brings a torrent of new releases, the majority concentrating on perhaps a few dozen canonical songs. There's a consequent pressure for new material. You can often track the progress of a song, from esoteric World Music nugget to holiday staple as you explore succeeding year's new holiday releases. The corpus of Christmas music is kept alive by the regular recruitment of songs from the dusty archives of the musicologists, to adoption by New Age or "Celtic" labels, into December PBS specials, and finally into the canon

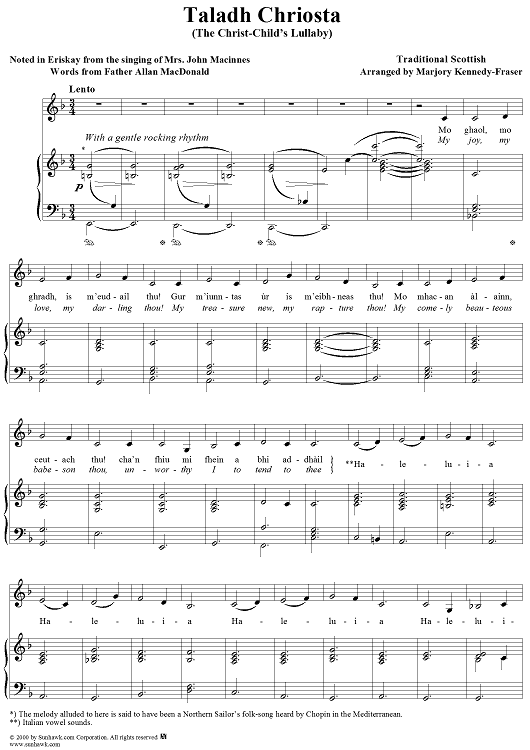

One song that is set to complete that progression any season now is the Scottish carol, the "Christ Child's Lullaby," or the Taladh Chriosda. According to Amazon.com, there are more than 120 recorded versions of the song currently extant. Of course, that's a mere blip compared to "Silent Night"; but when Judy Collins, Garrison Keillor, country star Kathy Mattea, jazz singer Dianne Reeve, alt-folkies like Shawn Colvin and Susan McKeown, ambient composer Richard Souther, and the United States Army band all cover a song, you know it's poised to become a standard. And through all the variations and stylistic experiments the song has been put through, and all the ones it will go through, and all its increasing familiarity, it still brings into the Christmas repertoire a haunting air of the storm-battered islands of the Scottish Hebrides where it was born.

The Hebrides are as close to Atlantis as they are to Valhalla…At first look, the Hebrides—in the Atlantic off the northwest coast of Scotland—appear barren and desolate, a landscape that embodies bleak vicissitude, where all vegetation seems to have been blown away by the constant wind except for the moss clinging grimly to the rock and the tough green turf. They are not large islands; many of them can be walked across from end to end in a matter of a few hours. On the map, they look as if Europe, striving toward the west, had in a last effort scattered a desperate arc of tiny pebbles out into the Atlantic.

And bleak vicissitude is indeed part of the human story here. But if you looked at the landscape and the climate, and thought to yourself that the people here must be correspondingly bleak and dour (or else roaring berserkers like the Scandinavians), you would be surprised. Hebridean skies are not really sturm und drang settings for Valkyrie riders. Often there is a diffuse marine light on the islands, grey but infused with blue and green, so that the mist when it comes is colored more like a pearl than a shroud. The tutelary spirits of the Hebrides are not warrior maidens, but mermaids, and the shape shifting seal people. The Hebrides are as close to Atlantis as they are to Valhalla. And when you turn from the outer environment, and look into the imaginative world of the people of these islands, it is rich and deep, bright and vivid, and full of the same soft radiance as the air.

In the Hebrides they speak Scots Gaelic the better part of a millennium since it disappeared everywhere else. The people of the Hebrides remained Roman Catholic for centuries after the rest of Scotland went Calvinist. And who knows for how long they remained pagan after the Christian monks arrived? On the evidence of the early collectors of Gaelic song and oral tradition who began transcribing the memories of the islanders, there was still a living and dazzlingly rich and distinctive Hebridean folk culture well into the 19th and even 20th centuries, that fused Christianity with older traditions-prayer and magic worked in tandem, saints and angels shared the islands with fairies and selkies. Christ was in heaven and also in the hearth fires and the wild hills.

It is difficult for most of us to grasp how real and ever-present the Otherworld was to them. Most of us could live a year without necessarily thinking about God, ghosts, prayer, blessings, angels, about anything outside the scope of the five senses. In the Hebrides, awareness of another theater of reality was woven into the smallest daily tasks and transactions. The impact of this kind of awareness can still be vividly felt in what was saved by the researchers, folklorists, anthropologists and musicologists who, from the mid-19th century to the outbreak of World War I, recorded and preserved what remained of this culture. Best known of them is Alexander Carmichael, an Edinburgh census taker, who in 1855 began collecting stories and songs, incantations and runes from the crofters of the Outer Hebrides as a hobby, and ended up producing the six epic volumes of the Carmina Gadelica ("The Charms of the Gaels") and bequeathing Scotland a precious national treasure.

‘The Christ Child Lullaby (Taladh Chriosta),’ the Mignarda Lutesong Duyo (Ron Andrico and Donna Stewart), from the Duo’s latest CD, Duo Seraphim, available at www.mignarda.comBy coincidence, 1855, the year that Carmichael started building his collection was also the year the Taladh Chriosta was written down. So we have some idea of what the inner universe of the islanders was like at that moment. The music of the "Lullaby" gives us a notion of what the many songs, beautiful enough as they lie static on Carmichael's pages, might have sounded like when a Gaelic singer brought them to life.

In December of 1854, a few months before Carmichael would arrive, Father Ranald Rankin was getting ready to say goodbye to his congregation on the small Hebridean island of Moidart.

The early years of the 1850s were hard times on Moidart. But then hard was a relative term when it came to life in the Outer Hebrides. The potato blight that had laid waste to Ireland had struck the islands not long before, and many starved, though not as many as in Ireland. The main cash crop-ash made from burning seaweed for use in glass-making-was being drastically devalued as the industry developed new manufacturing processes. Many of the land-owners, often from the urbanized mainland, had their eyes on the much more profitable business of sheep farming, and were encouraging islanders, in more or less forcible fashion, to emigrate to Canada, America, or Australia, leaving them thousands of acres of wide open pasturage.

Father Rankin, a Gaelic speaker who had come to Moidart 16 years before, could see no way out for many of the families but emigration, and so had marshaled the resources of the parish to ease their transition where he could. In the 1850s, the he began to work with the Highlands and Islands Emigration Society, a charity that sponsored assisted emigration to Australia, and many hundreds of families took the opportunity to leave for a new life there.

The destination for many of the families from Moidart was the Australian settlement of Victoria. Many of the displaced islanders had only one language and that was Gaelic, the language barrier further isolating them in a strange land. By 1854 there were enough of them to petition the Bishop of Glasgow to send them a Gaelic-speaking priest. Father Rankin offered to go.

The Rankin Sisters, ‘Taladh Chriosda,’ performed as part of 1999 TV special, Christmas Cabaret.And so, in December of 1854, as the days grew shorter, Father Rankin—preparing to celebrate his last Christmas on Moidart—was deep in thought. His mind was on the the needs of his parishioners still on Moidart whom he would soon be unable to help any longer. And then there were the needs of his new congregation in a strange and primitive land with challenges he could only guess at. But there was something else, something more personal. He wanted to leave something with these people, something to remember him by, a memento, a "cuimhneachan," as the islanders called it.

Like other intelligent and imaginative people who came to the Hebrides in the Victorian age, Rankin had been deeply impressed and moved by the traditional arts of the islanders-the piercingly beautiful songs, and the strange luminous opulence of their stories. He knew that there were other priests who would be alarmed if they could look through the eyes of one of these islanders for even one moment. Though the islanders' devotion to Christ and his church was obvious and passionate, there was something about the world they inhabited that was not exactly "Christian" as it was understood on the mainland, in the cities. For the typical 19th century Christian, in the developed parts of Western Europe or North America, the ladder of creation began with man at the bottom, Christ halfway up, and God on the highest rung. In the Hebrides, all those empty spaces in between were filled in with a dazzling host of entities and powers. And though the islanders did not exactly worship any of these beings and powers-that would have been idolatry and paganism and that Father Rankin would not have permitted-yet they were careful to be on good terms with them. They were a strange people. You could look in their eyes and talk and laugh or cry with them, yet know in some way those eyes took in a different world than the one you lived in. Rankin had become aware soon after his arrival that many of the inhabitants were highly susceptible to trance. For instance, when a group of the women were "waulking"-softening the tweed cloth that the islands were famous for by rhythmically pounding with their fists hour after hour on yard after yard of the material-they would extemporize simple rhythmic songs until they hit on a groove where the song began to sing itself through them. Some of the women had a special knack for entering this dissociated state and they could guide the other women into it, coming back from the other side with a new song or at least an unsuspected variant that made an old tune new. Father Rankin had heard many such songs in his time on the island, and he could recognize the strange freshness and novelty of the melodies that arrived by that route. There was one particular waulking tune that had caught his ear with a fresh otherworldly beauty. It had the unanswerable quality of of the wind, or the surf breaking on the shore. And then he had a thought-they would love to hear one of their own simple tunes brought into church, set in the liturgy; and especially at Christmas, their most beloved festival. And why not give it pride of place - have it sung for the Midnight Mass on Christmas Eve, along with Easter Eve the two holiest moments of the whole year.

He sought out the young women who formed the waulking group in the village. Shyly, one of the older girls sang it for him. It was a song for the sea, a song to bless and protect the men on the green waves. That made sense-the sea was in it, you could hear that. It was a lullaby to be crooned to the rhythm of the waves that endlessly washed the shore of the island, rising and falling, rising and falling. The endless sea, and yet it was intimate, as intimate as the space between the mother and the child in her arms. He went back to the rectory and wrote it down, and as he annotated it he thought that it might be a way to bring the love of the Holy Family alive. To show the islanders that the Other World with which they were so familiar came close, closest of all, at Christmas. Could he bridge the gap between the wild runes of this island and the story that he as a priest had to tell? He thought of all the uprooted families of Moidart making the dangerous voyage to Australia. He began to write and it was as if the song led him on, suggesting new verse after verse, until he had twenty-nine Gaelic verses, each one evoking another fragment of the emotions of the homeless and outcast mother trying to charm a little circle of peace for her child with her singing.

Here in translation are some of Father Rankin's lyrics:

My love my pride my treasure oh

My wonder new and pleasure oh

My son, my beauty ever you

Who am I to bear you here?Haleluia, haleluia, haleluia, haleluia.

My love and tender one are you

My sweet and lovely son are you

You are my love and darling you

Unworthy, I of you

Haleluia, haleluia, haleluia, haleluia.Your mild and gentle eyes proclaim

The loving heart with which you came

A tiny tender hapless bairn

With boundless gifts of graceHaleluia, haleluia, haleluia, haleluia.

(And here is a link to the other 26 verses, in the original Gaelic.)

Father Rankin offered the song as a gift to the mothers and children of Moidart. Shortly afterward, he left the island for Australia "amidst the tears and lamentations of an afflicted people" as a local historian writes. Once arrived in Australia, he built a new church for his parishioners of local stone, and opened a school. He died on St. Valentine's Day 1863, at the age of 64.

The song, which he named the Taladh Chriosda, or "Christ Child's Lullaby," became a part of the life of the islands, sung each Christmas Eve in Gaelic at Midnight Mass all over the islands.

And there it would have remained if, in the early years of the 20th century, a remarkable woman had not come to the islands

Marjory Kennedy-Fraser (1859-1930) was one of the children of the famous Scottish Victorian singer David Kennedy. Along with her sisters and brothers she traveled the world with her father as he performed for exiled Scots in the farthest flung parts of the British Empire. In 1890, at age 33, Kennedy-Fraser's husband died of pneumonia and she became a widowed mother of two children. She began to make her living giving music lessons. But her heart and imagination had been touched by the current revival of interest in all things Celtic, and because of this interest in 1905 she came to the Hebrides, where she, too, was captivated by the songs she heard. She would spend the better part of the next 15 years hauling a cumbersome wax cylinder phonograph across the forbidding Hebridean landscape recording and notating songs that in another generation would largely pass out of living memory. In one song-hunting expedition in 1909, Kennedy-Fraser transcribed all 29 Gaelic verses of the Taladh Chriosda, as sung to her by a Mrs. John Macinnes of Eriskay.

The product of Kennedy-Fraser's untiring efforts was her magisterial three-volume Songs of the Hebrides published between 1909 and 1921, with a fourth volume, From the Hebrides, following a few years later. As a result of Kennedy-Fraser's own legendary public performances of her collected material, many of the songs became widely known and loved. In recognition of her work she was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1928. And so the Taladh Chriosda first crossed the Minch, the treacherous strait that separates the Outer Hebrides from the mainland.

The arrival of portable tape recording technology and the establishment of the long playing vinyl disc as the standard playback format opened new channels for the collection and dissemination of regional music. Armed with the new tools, a new generation of song collectors were again, inevitably, drawn to the Hebrides. Prominent among them was the legendary American ethnomusicologist and folklorist Alan Lomax (1915-2002), one of the greatest field collectors of folk music of his day, and surely the only man to be investigated for subversive activity by the FBI, the CIA and MI5 later to receive the National Medal of Arts from President Ronald Reagan.

On the summer solstice day of 1951, Lomax found himself at "a great ceilidh (a music and dance party) which ended at 3 a.m." on the remote island of South Uist. At some point Lomax turned on his tape recorder and captured the first recorded performance of the Taladh Chriosda, as sung by Mrs. Kate Nicholson and a group of 10 crofters (tenant farmers). (The recording can be heard on Songs Of Christmas From The Alan Lomax Collection, Rounder Select 1998.)

Lomax remembered the song. In 1957, he produced what was for the times a technically ambitious Christmas Day special for BBC Radio that coordinated live remote broadcasts of local singers and musicians from all corners of Wales, Scotland, Ireland and England. It was a groundbreaking use of communications technology to expose a whole nation to heretofore obscure local traditions. Many listeners in the more urbanized parts of the British Isles heard traditions from their own lands that would have sounded as outlandish as anything from their once far-flung empire (like the Welsh Mari Llwyd ritual, which involved carrying a horse's skull on a pole from house to house). In planning the production, Lomax made sure to send a crew to Barra, an island of roughly 23 square miles in the Outer Hebrides, with a population of under 1000. From there they broadcast Mrs. Flora MacNeill, with her baby on her knee, singing the haunting strains of the Taladh, in Gaelic, to all Britain. (The entire broadcast can be heard today on The Concert & Radio Series: Sing Christmas & the Turn of the Year, Rounder Select 2000.)

The American folk music revival of the 1950s and ‘60s was among other things a system for taking in obscure regional songs from the vast archives that had been husbanded by collectors and compilers like Kennedy-Fraser, Lomax, and the Smithsonian field researchers, exposing a mass audience to them, and turning them into beloved standards. One of the earliest of the new wave of American folkies to record the Christ Child's Lullaby was Judy Collins, on her 1962 album, Golden Apples of the Sun (now available as Maid of Constant Sorrow/Golden Apples of Sun, Rhino/Wea UK 2001).

But the "Christ Child's Lullaby" had to wait for the Celtic-New Age-World Music boom of the 1980s to start on the path to omnipresence. At this point in time there first appeared a commercially significant audience of listeners who had grown up with Andy Williams, the Chipmunks and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, who were ready to get adventuresome about Christmas music. Once again, as with the ‘60s folkies, there was a pressing need for material to feed the audience appetite, and once again a new generation of musicians looked to the past-again to the original collectors and archivists, but also to the coffee houses of 1960s London and New York. And there they found the Taladh/Lulllaby, a forgotten piece of old gold in need of only a little burnishing.

Though I have yet to hear "The Christ Child's Lullaby" in a department store or elevator, it won't surprise me when I do. And it won't bother me much, either. You cannot play this song falsely. In any environment, in any setting, there is something that snags the attention, which stops you, that turns the unlikeliest moments contemplative. I think I'll hear it not as a commercial colonization of sacred art, but as a small triumph for otherworldliness, the entranced mind of the old islands planting its flag in this parking lot world.

Listening To the "Lullaby" Today

As I noted at the start, there is a dizzying variety of interpretations of the "Christ Child's Lullaby" on offer at this moment. Only an obsessive would want more than a few, but your at-home Christmas programming would have a sad gap without at least one.

Interpreters of "The Christ Child's Lullaby" fall roughly into Celticist and Modernist camps. The Celticists include those with their roots in the folk music revival of the 60s, as well as New Age types and younger folkies interested in conjuring an atmospheric Celtic frisson. Modernists approach the song in a less hushed manner, reserving the interpreter's right to riff on a standard and let the chips fall where they may.

Here's a highly subjective guide to a few of the more notable versions.

The Celticists

For those who like to take their folk music straight, Jean Redpath, the foremost singer of traditional Scottish songs today, does a crystal-clear unaccompanied rendition on Garrison Keillor's A Prairie Home Christmas (Highbridge Audio 1995).Slightly less purist, the great Scottish-Irish band The Boys of the Lough, on Midwinter Night's Dream (Blix Street 1996), with full traditional instrumentation, do a respectful version while conjuring some Celtic goosebumps with plainchant-like "hallelujah's."

Dulcimer player, producer and record label founder Maggie Sansone has one foot in the New Age and one in creatively reconstructed ancient music. On A Scottish Christmas (Maggie's Music 1996) she fashions an atmospheric instrumental version with harpist Bonnie Rideout and guitarist Al Petteway that segues between two equally traditional versions of the melody.

American harpist Kim Robertson similarly bridges New Age and folk, and has recorded the "Lullaby" twice. The more recent rendition, on Christmas Lullaby (Gourd Music 2004), is lyrical and haunting.

A full-on, guns blazing Scottish Taladh Chriosda—and that means in Gaelic, with pipes—can be heard on A Celtic Christmas: Winter Ritual Song and Traditions (Saydisc 2009), sung by Arthur Cormack.

Modernists

Multiple Grammy-winning singer Dianne Reeves covers the "Lullaby" on Christmas Time Is Here (Blue Note 2004) where she finds a jazz mood that harmonizes with the archaic spirit while bringing the maternal emotions alive.

In a very different kind of jazz mode, folk-rock-jazz singer Susan McKeown performs what she calls "The Christ Child" on her amazing Through the Bitter Frost and Snow (Prime CD 1997). Like the great interpreter she is, she locates particularly resonant emotions in the material, as when she sings "the cause of talk and tale am I" and in an instant suggests the dilemma of a young woman with a suspicious pregnancy in an impoverished Middle Eastern village.

Composer Richard Souther, best known for his album Vision: The Music of Hildegard of Bingen, wanders down a path distinctly his own in his take on the Taladh Chriosda. It's the most effective cut on his ambient Christmas concept album Tesla's Christmas (Northersouth Music 2009), proving that it's hard to out-ambient the Gaels.

More than any of the other Modernists, Lilith Fair stalwart Shawn Colvin scores the dubious distinction of utterly contemporizing the "Lullaby" by ironing out the song's last wrinkle of mystery with her vernacular rendition on Holiday Songs and Lullabies (Sony 1998)

Finally, modern country giantess Kathy Mattea joins the United States Army Band on A Holiday Festival (CreateSpace 2008), where the song wins out over an unblushing MOR arrangement on the strength of Mattea's evident emotional connection with the material.

The Best

And the nod for the best extant recording of "The Christ Child's Lullaby" (on A Christmas Celtic Sojourn, Rounder 2001) goes fittingly to a Scot, traditional singer Sheena Wellington, who brings it all home in a rendition that rekindles the old song's otherworldly heart by marrying a reverent reading with the application of ambient electronics that even an ancient Gael could hardly disapprove of.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024