See You Later, Alligator…

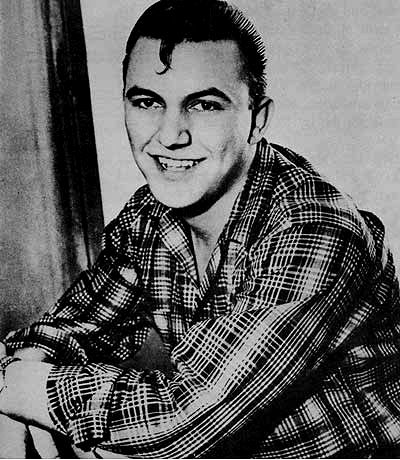

Bobby Charles

Louisiana songwriter dies at 71

By Keith Spera

The Times-Picayune, January 14, 2010, 1:39 p.m.(Ed. Note: Louisiana’s Bobby Charles, one of the greats of American roots music, died on January 14. Of the many tributes to Charles that we came across, none were as moving or as well crafted as Keith Spera’s in the Times-Picayune. Spera did right by the legend.)

Abbeville, LA—Robert "Bobby" Charles Guidry, the gifted, reclusive southwest Louisiana songwriter who crafted hits for Fats Domino, Frogman Henry and Bill Haley & the Comets, died early Thursday, January 14, after collapsing at home, his manager said. He was 71.

Known professionally as Bobby Charles, he wrote "Walking to New Orleans," one of the most beloved songs in Domino's catalog; "(I Don't Know Why I Love You) But I Do," an enduring classic by Henry; and "See You Later Alligator," a smash for Haley in the early years of rock 'n' roll.

He counted Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Willie Nelson and James Taylor among his friends and fans. A reluctant performer, he largely disappeared from the public eye after participating in the Band's legendary 1976 farewell concert "The Last Waltz." He preferred to release the occasional album while living anonymously outside Abbeville, an enigma whose songs were more famous than he was.

Mr. Charles initially agreed to a "comeback" performance at the 2007 New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival presented by Shell, only to beg off at the last minute, citing health issues. Mac "Dr. John" Rebennack, Marcia Ball, guitarist Sonny Landreth and other fans performed his songs in his absence.

Mr. Charles grew up poor in Abbeville. His father drove a truck for a gas company, delivering 50-gallon fuel drums to far-flung farms. At 14, he joined a band that entertained at high school dances around Abbeville.

‘Queen Bee,’ a tribute to Bobby Charles, includes vintage live photos of Charles, and slide guitar master Sonny Landreth’s succinct take on working with the Louisiana music legend as recounted in his own liner notes for Charles’s Homemade Songs album: ‘Whenever B.C. calls me up and says, ‘Sonnyman from Sunnyland!” I know it’s a full moon and he’s ready to record again. I also know the session will be like some kind of wildly creative circus that’s come to town and I don’t want to miss the rides. Truth is, his voice and his songs are the heart and soul of South Louisiana’s all time greatest and for that he is our world champion. Now, if I can just get him to show up for a live gig.’"Nobody in my family wanted me to get into the music business, but I always loved it," he said during a 2007 interview. "The first time I heard Hank Williams and Fats Domino, it just knocked me down. When I was a kid, I used to pray to be a songwriter like them. My prayers were answered, I guess."

Leaving a cafe one night, Mr. Charles bid farewell to friends with "see you later, alligator." As the cafe door closed behind him, a drunken stranger replied, "after 'while, crocodile." Not sure he heard correctly, he went back inside and asked the stranger to repeat it.

That couplet inspired him to write "See You Later Alligator." He sang it over the phone and landed a recording contract, sight unseen, from Chicago blues and R&B label Chess Records. The company's owners assumed he was black until he stepped off the plane in Chicago.

As a burgeoning teen idol, he hit the road with other Chess artists, the only white guy on the bus. Not all audiences appreciated such integration. The threats soured him on touring. So did the occasional bullet fired his way.

"I never wanted to be a star," he said. "I've got enough problems, I promise you. If I could make it just writing, I'd be happy. Thank God I've been lucky enough to have a lot of people do my songs."

Bill Haley & His Comets perform Bobby Charles’s ‘See You Later, Alligator’ in the 1956 jukebox musical, Rock Around the ClockIn the 1970s, Mr. Charles wrote a song called "The Jealous Kind." Joe Cocker recorded it in 1976, followed by Ray Charles, Delbert McClinton, Etta James and Johnny Adams. Kris Kristofferson and Gatemouth Brown covered Mr. Charles' "Tennessee Blues," as did newcomer Shannon McNally. Muddy Waters recorded "Why Are People Like That"; so did Houma guitarist Tab Benoit on his Grammy-nominated 2006 album, Brother to the Blues.

He could not play an instrument or read music. Songs popped into his head, fully formed. To capture them, he'd sing into the nearest answering machine; sometimes he'd call home from a convenience store pay phone.

"I can hear all the chords up here," he said, pointing to his brain, "but I can't tell you what they are."

In his younger years, he ran around with the likes of Bob Dylan, Neil Young and Willie Nelson, and raised all kinds of hell. His rogue's resume included scrapes with the law, a busted marriage, and too much of too many things.

"To love and lose—I know that pain," he said. "And cocaine killed so many of my friends. (The Band pianist) Richard Manuel hung himself. (Blues harmonica ace) Paul Butterfield OD'd."

Bobby Charles, ‘Take It Easy, Greasy,’ Chess single 1628, released 1956For a time in the 1970s, he laid low in Woodstock, N.Y. But mostly Charles holed up in the bosom of south Louisiana, waiting for the next song to come along.

Or the next calamity.

For years, he lived on the Vermilion River outside Maurice, La. In the mid-'90s, his house burned to the ground with all his earthly possessions.

With nowhere else to go, he moved into a trailer on the grounds of Dockside Studios in Maurice. Despondent, he hit the road with one of his four sons and washed up at Holly Beach, a forgotten hamlet with 300 permanent residents on the Gulf of Mexico southwest of Lake Charles.

"I'm a Pisces. I love water," he said. "There's nothing like a wave to wash away your problems and clean out your mind. Well, it doesn't wash 'em away, but it helps."

He bought a house facing the Gulf, and the two houses next door, to eliminate the possibility of neighbors. He also snapped up the surrounding lots to protect his view.

In Holly Beach, Mr. Charles disappeared for a decade. But in the summer of 2005, Hurricane Rita found him. He escaped just ahead of the storm, then later returned to find his house had washed away.

The reclusive songwriter preferred to live quietly, out of the limelight.He moved to a two-bedroom trailer amid the grand oaks of an eight-acre property outside Abbeville. He kept his address and phone number secret, and cast a wary eye toward strangers and acquaintances alike.

"They all want to meet Bob Dylan or Willie Nelson. They say, 'Man, I got a song for Bob Dylan.' I think Bob Dylan writes most of his own. So does Willie. I don't even sing any of mine to them.

"Some people have to depend on somebody else to make a living. And that gets tiresome, man, carrying a load like that. It gets to the point where you're afraid to open your mouth in front of anybody."

Bobby Charles, 1955: He could not play an instrument or read music. Songs popped into his head, fully formed. To capture them, he'd sing into the nearest answering machine; sometimes he'd call home from a convenience store pay phone. (Photo: Bill Greensmith)Despite being swindled out of publishing rights and shares of his songwriting credits years ago, his annual royalties afforded him a comfortable living. When, for instance, Frogman Henry's version of "But I Do" landed on the Forrest Gump soundtrack, Mr. Charles received a royalty check.

Mr. Charles was happiest in the studio. In 2003, he and his manager, Jim Bateman, gathered recordings spanning 20 years for the double-CD "Last Train to Memphis," released via Charles' own Rice 'n Gravy Records. Special guests included Neil Young, Fats Domino, Willie Nelson, Delbert McClinton and Maria Muldaur.

Mr. Charles' voice, graced with a slight, Randy Newman-esque drawl, was still strong, as was his gift for pairing lyrics and melody. He was due to release a new album next month.

But he was unlikely to hit the road to promote it. In recent years, he tended to keep to himself. Most days, he ate alone at an Abbeville seafood joint where the waitress mixed his preferred cocktail—a Grey Goose martini on the rocks—as he parked his car. "I don't really have anybody," Mr. Charles said in 2007.

"I just don't have a whole lot in common with the people I went to school with. I still love them as my friends, but I don't have anything to say to 'em. They wouldn't believe half the (stuff) that happened to me anyway.

"But when I get around Mac Rebennack or Fats or somebody like that, then I'm in my world."

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024