Sharon Isbin:‘I’m very gratified when women write to me or meet me after a concert and say how much I’ve inspired them to play the guitar. It means I’m having some kind of impact.’Sharon Isbin

The Journey Inward, And Forward

TheBluegrassSpecial.com Interview

By David McGeeTake the gender issue out of the question as to whom is the preeminent classical guitarist in the world and Sharon Isbin will still rank in the top five, if not the top three, on most knowledgeable observers’ lists. If the talk is centered on gender, she’s number one, unequivocally. (The one who might be considered her main competition, England-born, Canada-bred Liona Boyd, who preceded Ms. Isbin on record, with her debut coming in 1974, was diagnosed in 2002 with the disabling neurological condition focal distonia, which affects her fingers' ability to function, essentially; she has since directed her efforts in a pop direction as a vocalist.) There’s nothing in her history to suggest she has reached this plateau through any route other than hard work and rigorous discipline coupled to a fierce intellect. She’s really earned the multitude of accolades that have come her way since her recording debut in 1978.

Born August 7, 1956 in Minneapolis, Ms. Isbin took up the guitar at age nine, while living in Varese, Italy, where her family had relocated during her professor father’s sabbatical from the University of Minnesota. Her brother had turned down an opportunity to study with a legendary teacher in Varese because the lad would rather have been Elvis Presley than Andres Segovia. So, heeding her parents’ insistence that someone in the family had to study with this particular teacher, young Sharon stepped up. To say she was a quick study is to be guilty of understatement: by age 14 she was concertizing, and before age 16 her teachers included the most monumental name in classical guitar, meaning Segovia, and, the one who continues to have the most impact on her life and art, Dr. Rosalyn Tureck, the noted Baroque pianist—yes, pianist. Since age 16 Ms. Isbin has essentially been self-taught, and now she is a teacher herself, as the head of the guitar department that she founded at New York’s prestigious Juilliard School and at the Aspen Music Festival.

But this doesn’t even begin to catalogue her achievements. In fact, it would take a whole feature story unto itself simply to list all the honors that have come her way and all the breakthroughs she’s made in bringing classical music to a larger audience and to establishing a higher public profile for the guitar in a classical setting. When she began her career the guitar was very much a second-class citizen in the classical world, women even more so—in fact, she and Ms. Boyd were the first female classical guitarists of note since the extraordinary Ida Presti, who died young in 1947 and left behind only a few scintillating recorded examples of her brilliance. Since launching her recording career in 1978 with the Sound Environment Recording Series album Classical Guitar (which featured compositions by Leo Brouwer, Isaac Abeniz, Jose Fernando Marcario Sors, Manuel Maria Ponce and Antonio Lauro), followed in 1980 by Classical Guitar Vol. II (comprised of a repertoire from Leo Brouwer, Johann Sebastian Bach and Benjamin Britten), she has more than 25 albums to her credit as a solo artist, and celebrated collaborative projects such as being the featured soloist on the Grammy nominated soundtrack to Martin Scorsese’s film The Departed. She has won two Grammys—in 2001 as “Best Instrumental Soloist Performance” for her top charting Dreams Of a World album (she was the first classical guitarist to receive a Grammy in 28 years); and in 2002 for her self-titled album on which she gave the world premiere performances of concerti written for her by Christopher Rouse (“Concerti de Gaudi for Guitar and Orchestra”) and Tan Dun (“Concerto for Guitar and Orchestra”). Her 2005 album featuring Joaquin Rodgrigo’s “Concierto de Aranjuez” and concerti by Mexican composer Manuel Ponce and Brazilian Heitor Villa-Lobos marked the first time the New York Philharmonic had ever recorded with a guitarist, and Ms. Ibsin became the Philharmonic’s first guitar soloist in 26 years when she and the orchestra teamed up at Lincoln Center’s Avery Fisher Hall; the album also was nominated for a Latin Grammy as “Best Classical Album” and received a 2006 GLAAD Media Award nomination for “Outstanding Music Artist.” Other Grammy nominated projects of hers include her 1999 Journey To the Amazon, with Brazilian percussionist Thiago de Mello and saxophonist Paul Winter (nominated for “Best Classical Crossover Album”); and Double Concerto, a 2000 project with violinist Cho-Liang Lin and the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra. From these titles alone a story emerges of an artist who has been busy crossing musical borders all her career—from Baroque to Latin to folk to jazz, from Renaissance times to the 21st Century. She has also expanded the repertoire for guitar significantly, having commissioned more guitar concerti than any other guitarist, and from a range of stylists, not only classically oriented but including film composer Howard Shore (who scored The Departed, among others) and rock guitar slinger extraordinaire Steve Vai. Her 1995 album gem, American Landscapes, with the Saint Paul Chamber Orchestra conducted by Hugo Wolff, is the first-ever recording of American guitar concerti, with works commissioned by her from John Corigliano, Joseph Schwantner and Lukas Foss, and it literally went out of this world, being launched in the space shuttle Atlantis and presented to Russian cosmonauts during a rendezvous with the Mir space station.

And this is only accounting for her recording career. She has toured the world annually since age 17, has played with every prestigious orchestra extant and appeared as a soloist with more than 160 orchestras in the U.S. alone. She works in smaller configurations as well, as a chamber musician, and in this context has significantly broadened her musical horizons and those of her audience as well, by performing with the likes of Mark O’Connor, Steve Vai, the great mezzo-soprano Susanne Mentzer, the Emerson String Quartet and others; she has participated in “Guitar Summit” tours with revered jazz artists such as Herb Ellis, Stanley Jordan and Michael Hedges, and collaborated with Antonio Carlos Jobim and on trio recordings with Larry Coryell and Laurindo Almeida. Clearly, as an ambassador for classical music and classical guitar, and as a proponent of fearless exploration of crossover possibilities from classical to other genres, Sharon Isbin has few peers on the contemporary scene.

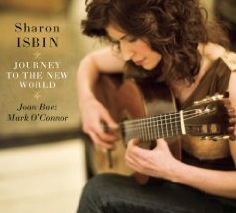

Which brings us to the present day and yet another Grammy nominated album, her latest, the breathtaking Journey to the New World, her first long player since 1999’s Dreams of a World in which her guitar is unaccompanied by an orchestra or small group (only the appearances of Joan Baez, singing two numbers, and Mark O’Connor, playing fiddle on his own “Strings & Threads Suite,” depart from the solo guitar setting). It resonates with references to Ms. Isbin’s professional and personal history, featuring, for starters, not one but two world premiere recordings, including a suite of Joan Baez songs composed for her by the towering guitarist John Duarte, who passed away in 2004 shortly after completing the “Joan Baez Suite,” which is comprised of a Fantasia on “Once I Had a Sweetheart,” “Rambler Gambler” and “Barbara Allen”; plus “The House of the Rising Sun,” The Lily of the West,” “The Unquiet Grave” and “Silkie.” The other new work is by Ms. Isbin’s friend and fellow border crosser, Mark O’Connor, who is coming at classical from the opposite direction as she, after starting in bluegrass, country and folk. To this album O’Connor contributes his short course on folk music history, “Strings & Threads Suite,” which takes player and listener on a fast ride (of the 13 parts the longest is the achingly beautiful “Shine On”—which happens to feature one of O’Connor’s most exquisite and haunting fiddle solos on record—at a minute, 49 seconds) through reels, jigs, blues, swing and country styles, stopping, as Ms. Isbin has noted in other interviews, “at the doorstep of bluegrass.”

Beyond her signature commissioned works, though, pretty much the entirety of Journey to the New World speaks to her own journey: the tender, hushed opening of “Four Renaisssance Lute Works” returns her to music she has been performing practically her entire career (she has recorded an entire album of J.S. Bach lute suites, and her 2003 album for Warner Classics, Sharon Isbin Plays Baroque Favorites for Guitar, with the Zurich Chamber Orchestra, is a work of inestimable beauty). “Two English Folksongs” (“The Drunken Sailor” and a beautiful, ruminative “Wild Mountain Thyme”) and Andrew York’s “Andecy,” with its intriguing contrasts of dark and light, serenity and anxiety, once again underscore her career-long immersion in folk music. In an interview with the New York Times in 2001, Susanne Mentzer described Ms. Isbin’s knowledge of folk repertory as “incredible. She has such a good sense of folk music. She spends a lot of time trying to make sure it’s perfect.”

Ms. Mentzer herself is present on Journey to the New World, not in fact but in spirit by way of the haunting folk song “Wayfaring Stranger,” which was the title track of an acclaimed 1998 album featuring the guitarist and mezzo-soprano on a globe spanning selection of folk and folk-influenced material, some of it traditional, some of it from the pens of John Jacob Niles and Franz Schubert alongside some gems from the obscure composer Matyas Seiber. Here, though, the song is revisited not with Ms. Mentzer but with Joan Baez, the artist Ms. Ibsin cites as her first musical hero. In fact, Ms. Baez appears twice, and memorably, as Ms. Ibsin chooses to revisit yet another song from the Wayfaring Stranger album, the aforementioned John Jacob Niles’s “Go ‘Way From My Window.” Those who have not kept up with Joan Baez of late are in for a surprise, because her voice, now deeper and huskier than in her younger, folk rabble-rouser era, is even more expressive than in days of yore, and richly colored with experience, so much so that the subtext, the shading, of her readings is as affecting as the sentiments voiced in the lyrics. And to further emphasize the stock-taking aspect at work here, Lukas Foss’s “American Landscapes for Guitar and Orchestra,” the title composition from the album that went into outer space, includes in its second part variations on “Wayfaring Stranger.” Of course the constant is Ms. Isbin’s impeccable guitar work, whether soloing with intense feeling, precision noting and witty punctuations on the Renaissance and folk tunes; or subtly supplying restrained, atmospheric color behind Ms. Baez’s moving interpretive singing; or bobbing, weaving and otherwise engaging in spirited discourse with Mark O’Connor in a peak performance by both on “Strings & Threads Suite.”

TheBluegrassSpecial.com caught up with Ms. Isbin at her Upper West Side apartment two weeks prior to her venturing to Los Angeles to appear on the Grammy pre-show Internet broadcast, in which she was going to be teamed in an instrumental blowout jam with an all-star lineup of bluegrass musicians including Bryan Sutton, Michael Martin Murphey and Alison Brown. Though she seemed to be taking everything in stride, she did betray a tiny bit of anxiety about being thrust into this role—which, by the way, was causing her no second thoughts at all about participating, though she did remark as to how she didn’t expect to be making her bluegrass debut in quite this manner or quite so publicly.

“I thought maybe we could try it out in a coffee shop first,” she said with a gentle laugh, “or something. I said I need a part and an MP3 to study because I don’t improvise!”

Dressed casually in blue jeans and a light sweater, her rich mane of brunette hair flowing about her shoulders, Ms. Isbin speaks with the same tenacity she brings to her research and playing. Talking to her is much like conversing with Mark O’Connor, in that both are direct, thorough and confident in their responses, neither is short on detailed answers, both have thought through their work and know how to explain it in depth, both say what needs to be said without getting overly technical about their methodologies, unless they’re asked to do so. O’Connor, nine years younger than Ms. Isbin, has actually been recording longer than she, his first Rounder album coming in 1975 (following in independent release in 1974 of his National Junior Fiddling Champion album), but they intersect at the junction of traditional American and classical music and are actively engaged in advancing what O’Connor calls “a new American classical music” that embraces exactly what Ms. Isbin showcases on her latest album—tunes from all over the world that have found their way, wholly or in part, into the lexicon of American traditional music and now form the foundation for a fresh, original repertoire expressed in templates constructed centuries ago. But we begin with her sense of the larger theme of Journey to the New World as it relates to her personal journey.

***

I’m wondering if on some level you might hear this album as a summation of where you’ve been to date. The reason I ask that is because the content of the album is so resonant with your history: you have a history recording lute music, and lute music begins this album; obviously folk music from distant lands has been part of your recording history and in concert; and certainly the American strain, represented on the new album most dramatically by the contributions of Mark O’Connor and Joan Baez, has been strong in your body of work, too, with John Duarte’s “Appalachian Dreams”—

Sharon Isbin: And Lukas Foss and John Corigliano [Ed. Note: As previously noted, Foss’s “American Landscapes” was the title of Ms. Ibsin’s 1995 album, which is further distinguished by being taken aboard the space shuttle Atlantis; John Corigliano’s “Troubadours (Variations for Guitar and Orchestra)” is the lead track on American Landscapes.] I never thought of it that way, but you’re right—it really is a metaphor for so much that has been a part of my life and the growth in my life. Certainly my first association with the guitar was with folk music. I started on guitar when my family took a sabbatical to Italy, and my older brother asked for guitar lessons. His fantasy was to be the next Elvis Presley, but my parents didn’t know that. They found this great teacher who had studied with Segovia. When my brother realized it was classical, his reaction was, “I’m not doing that.” My parents were like, Someone in this family has to study with this teacher—he’s something remarkable. So I said I would do it. My association was with folk music and I figured how far afield could this be? So this in a way is coming back to my roots. And I would say this whole process has been inspired by that genre, which is very integrated in people’s lives. It’s about telling stories in ballads, and the history of dreams and hopes and loves and struggles, and oppression and redemption, and joy—folk music is about people’s stories and about their journeys in life. That’s what has always drawn me to this style of music. It’s meaningful.

Apart from the music that you commission, are you drawn to music first for its emotional content, or do you look for some technical aspect that challenges you above all else?

Isbin: I would say first it has to speak to me. And if I get goosebumps from listening to something, I know I’m finding a treasure. And that often is the test when I’m picking works to do on a new recording. I also want to diversity the nature of the music so that it’s not all slow or all fast, so there’s a mixture of virtuosity with lyricism, but the bottom line is the music has to reach me. Has to be something moving and compelling.

Sharon Isbin in 1981, performing Bach’s Lute Suite No. 2 DoubleOn this album, among the songs you perform is “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” which has been around for awhile and is very much identified with the ‘60s and the Vietnam War. And towards the end you slip in a little phrase from “Taps.” Which really makes a listener sit up and take notice, gives it some added emotional heft.

Isbin: Well, the arrangement and the setting were by John Duarte. That was all his idea, and I think a very poignant one, because certainly the flowers were the veterans who never returned from the Vietnam War and that’s very much a statement of what we’re involved in now. It moves me every time I hear that. It renders the piece even more contemporary in its societal implications.

And in another song that’s familiar, “Greensleeves,” in the opening Lute Suite, you play with the tempo and melody in a way that almost makes it into a new song.

Isbin: It’s a magical setting. It’s by a 16th Century composer whose last name is Johnson, and he was a lutenist. And he set this for two lutes. So I play both parts. We don’t really think of “Greensleeves” as going back as far as the 16th Century, but it does, and it’s a really magical, haunting and very lyrical, fun kind of piece. What I infuse into it is the different colors that you hear. For example, if I’m playing right by the bridge, you get kind of a metallic sound; if I move my hand up, I get a dolce, kind of caressing sound. All of these are the kinds of colors you can have, say, in a Renaissance band, except I’m all the instruments at once.

How did you go about selecting the Renaissance lute music to open the album?

Isbin: Well, this is one of the great advantages of heading the guitar program at Juilliard. I get some really brilliant students, and one of them approached me about seven years ago with this idea. I guess it was because he was going to be my assistant at the Aspen Music Festival. He wondered if I might want to do some duets with him. I said, “What do you have in mind?” Because his specialty had grown in the direction of Baroque and Renaissance. He played these pieces for me and I fell in love with them. I actually selected four out of his set and performed with him in Aspen and enjoyed it so much I asked him to play with me at my big New York concert. I knew in the back of my mind that one of these days I would record them, because it was just so special.

Did you do any research into the history of the songs?

Isbin: Oh, sure, and tablature with the embellishment markings on them. One of the things that is fun for musicians of our time to know is that Baroque music and Renaissance music was the jazz of their time. And the performers would improvise the variations and the repeats, so you would have a spontaneous, on the spot kind of personal inflection in the interpretation. So you’ll hear different trills and passing tones and all kinds of things that change when you come back and do the repeats, very much the way a jazz musician today would embellish his part. I had a lot of fun with that, and having spent so many years, ten years, studying with Rosalyn Tureck, the great Baroque pianist and scholar of our time, and learning about Baroque performance practice, it translates very well to pre-Baroque.

What is the challenge of the lute songs for a guitarist?

Isbin: One of the things that I wanted to do was to sound more like a lute. So I used a capo on the second fret, and that automatically brings the guitar into that slightly more lute-like timbre. One of the advantages we have as guitarists over lutenists is that because we play with our fingernails, a bigger variety of tone colors is possible. So I’m not trying to be a lutenist, I’m trying to be expressive of this music in the character of its time but on an instrument that has even more versatility.

What is your guitar of choice?

Isbin: The guitar I used on that album is by Thomas Humphrey, and it’s a rather remarkable instrument. He passed away, unfortunately, in the past year. He had built this instrument especially for me. It’s a cedar top, has a very warm, dark chocolate sound to it, and very fitting for the music in this album. It also has a beautiful sustain, which allows you to play lyrically very well, and the back of it is painted with two beautiful muses that are part of the figuration of the grain of the wood in terms of their hair, but their faces and eyes are painted on. It’s very, very lovely. It’s the first time I used that guitar on this recording. I’m also now playing an instrument by Michael O’Leary from Ireland. A cedartop as well, but a whole different kind of instrument.

Sharon Isbin and Joshua Bell perform Niccolo Paganini’s ‘Cantabile’ at the White House Evening of Classical Music, Nov. 4, 2009This is the first album since 1999’s Dream Of a World that we’re hearing, apart from Joan and Mark’s contributions, only you and the guitar. No other players. Was that the idea going in, or was that a product of the type of material you came up with?

Isbin: Originally it was going to be an all-solo album; that was my thought, to do another Dreams of a World-type album. And then Joan Baez offered to sing on it, and I thought, Wow, this is beyond my most wonderful, possible fantasy. She’s my folk hero. When she heard the “Joan Baez Suite” by John Duarte, she offered to sing. So she joins me on “Wayfaring Stranger” and “Go ‘Way From My Window,” really haunting renditions. And coincidentally, the same time period where I was going into the studio and recording with her, I was preparing a premiere with Mark O’Connor of his “Strings & Threads Suite” that he had set for the two of us. We did that premiere in Minneapolis in 2007. I said to Mark afterwards, “This is incredible. This would fit so perfectly on the album. Would you join me in the studio next month?” So it happened rather spontaneously, and I like it when things go in that direction. And the album became an evolution of folk music, where you look at the musicians in the 16th Century British Isles, and moving towards 17th and 18th Century Scotland and Ireland with “Wild Mountain Thyme” and “Drunken Sailor,” which is actually inspired by an even older form that was a song tribute to the famous Pirate Queen, Grace O’Malley. Then Andrew York’s “Andecy” is a perfect bridge between the British and the American, as his work was inspired by that whole culture crossing the ocean, immigrants who came in search of a better life, like Mark O’Connor’s family, potato farmers who tried to forge their lives in the new world. And this music becomes transformed—you have the whole world of Appalachia, the beginning of bluegrass. It’s a fascinating history and it’s all very, very connected. In a way Mark’s suite brings all of that together, as does the Joan Baez suite, because you hear all the old Irish influences, the Scottish and how it becomes a new language in the colonies and in the new world.

With Joan you revisited two songs you had recorded previously on an album with Susanne Mentzer. Why did you revisit songs you had done previously rather than have her perform something else?

Isbin: I wanted to choose something Joan Baez had recorded in the past, so it wouldn’t be involving her learning something new. And I was just gung-ho that the arrangement of “Wayfaring Stranger” by Carlos Barbosa-Lima would be one of the pieces. [Ed. Note: Ms. Ibsin and Barbosa-Lima recorded a duet album in 1987 for Concord Picante, Brazil, With Love, with liner notes by Antonio Carlos-Jobim.] I gave her the option of several to choose, and these were the ones that rose to the top. I also didn’t want it to be something that was a signature work of hers, something that was very much associated with a particular arrangement. For example, “Farwell Angelina,” we can’t separate that from its original recording in our minds. I felt it was better to do something that would be taking her to a different realm, but yet using material that was somewhat familiar. If you listen to Joan Baez’s recording of “Wayfaring Stranger” from way back, a few decades ago, it’s completely different—different time signature, different tempo, whole different spirit and mood. You wouldn’t even know it’s really the same piece. I knew that this arrangement would bring it to another place, so it would be interesting for her; it would be something new but yet a revisiting. And that’s exactly how it turned out.

She is so deep inside those songs it’s remarkable. I’ve heard her in recent years, on record and in person, but she took herself to a whole other level of emotional investment on these performances.

Isbin: I agree with you completely. I would cry every time I listened to “Wayfaring Stranger.” Her rendition of that moved me so much. It is imbued with the experiences of her lifetime, of her personal losses, her vision of the world—it’s magnificently touching.

And you’ve described her as the first musical idol you had in your life.

Isbin: She’s the only person I ever wrote a fan letter to in my life. I was 23 years old, and I had been describing to a friend how incredibly powerful her music was for me and how it moved me beyond words. My friend said, “You should write to her.” I’m sure she never got the letter. But it was cathartic to think that the seeds of this recording really were born several decades ago.

Did she have an impact on your own music? You’re not a singer, you’re an instrumentalist.

Isbin: Well, absolutely, because the lyricism in her voice, the shaping of the line, the inflection, the magic about how at one she is with it and how transportive it is, certainly that has affected my music. Because for me the greatest inspiration as a guitarist is to listen to singers. So whether it’s Joan Baez or Elly Ameling, or Renee Fleming or whoever it is, the shaping of the vocal line, that’s key to becoming a lyrical musician. And on the guitar that’s especially challenging because we have to pluck each note; we don’t have a bow to carry through or the breadth of a wind instrument. It’s something we have to create the illusion of, and it’s very possible to do that. But a voice will inspire in me that direction.

Sharon Isbin and Mark O’Connor at Symphony Space, New York City, January 2009. Isbin played John Duarte’s ‘Lily Of the West’; with Mark O’Connor she performs ‘Swing’ and ‘Sweet Suzanne,’ from O’Connor’s ‘Strings and Threads Suite,’ featured on Ms. Isbin’s Grammy nominated album, Journey To The New WorldWith Mark, it wasn’t like you just went in and right away cut the “Strings & Threads Suite.” You’ve said some work had to be done.

Isbin: It was a moment of terror. What happened was I made an assumption—and it’s always dangerous to make assumptions. Mark is a brilliant flatpicker guitarist as well as a violinist. So when he gave me the part I glanced at it and thought, Well, this is gonna be great. I didn’t even look at it until about a month before we were to premiere it. And I got scared out of my wits, because no matter how much I practiced, I couldn’t play it, or parts of it—the fast things. I’m working with the metronome and suddenly realized, Wait a minute—this has to be revised because there are a lot of things here that don’t work on the instruments. Jumps that are too high, too many notes in a chord, speeds that are great for a picker but not might work for classical technique (laughs). So at our first rehearsal we spent seven hours going over it measure by measure just to make revisions in the voicing and in some of the notes to make it perfectly idiomatic. And it turned out he’d never tried it out on guitar—he’d done it all in his head. So the joke became, when he took the guitar off the wall, “Mark, if you can play it, then I’ll play it.” That was the true test. So the next day we spent another eight hours working on the score, and by the end of those two days we had something really to be proud of that was sophisticated and virtuosic for the instrument, but still very idiomatic.

There are so many moments in the suite that are pure Mark, but he has a little solo in the “Shine On” section—

Isbin: Oh, yeah…

You know what I’m talking about…

Isbin: Yeah.

It’s one of those moments when you have to sit down, dab your eyes, because it’s so sweet, so tender, and it comes out of nowhere to steal your heart.

Isbin: And the same thing in the one about the sailor who has gone to sea and it’s a widow mourning the loss of her husband, who is never going to return from a seafaring trip. You can just picture her pacing in a widow’s walk and it’s very heart wrenching, and really special to play as well because it’s very tactile in its moving quality.

Mark is so disciplined and so precise in conversation. How is he in the studio?

Isbin: Same thing. We’re similar in that we’re very meticulous about things and we’re very devoted and dedicated to our art, and whatever amount of work is necessary to make it happen we do that. Mark has so many projects going it’s remarkable. I asked him at one point, “Do you ever sleep?” I’m known for my four- and five-hour nights sometimes, but he does it every night. So I don’t know how he survives, but he’s a great guy. Lovely, lovely to work with.

John Duarte is someone you had a history with before this record, and quite a fruitful one with his “Appalachian Dreams” from your Grammy winning Dreams Of a World album in 1999. How did his “Joan Baez Suite” on your new album come about? Did he offer it to you? Did you commission it?

Isbin: Well, after the success of “Appalachian Dreams” and the CD got a Grammy, he said, “I’d really like to write something else for you.” So I said, “What about something in a similar type of creative arrangement vein but based on songs that Joan Baez made famous?” He said, “I love the idea. I’ll do that.” The same way we worked on the other piece we did on this one: we did some research and came up with a wish list of possible songs that could be part of it, and the one I really insisted on was “Where Have All the Flowers Gone.” Then he selected the works that would be part of the seven-movement suite and presented it to me. That was it.

Did you make any alterations to what he presented to you?

Isbin: No, because he’s a guitarist. He knew what he was doing. But I did have a chance to work with him before he died. It would have haunted me forever if I had not had a one-on-one session where I’m playing for him and getting critiqued and being able to ask questions about tempo and colors and phrasing. I almost didn’t have it, because he was very ill with cancer and I was away for the summer. I had to go to Berlin to do the final mix of my recording with the New York Philharmonic. I was hoping he would still be alive so I could stop by in London. And he rallied, and we had just a wonderful day together, really very powerful, and I felt fortunate that I had that opportunity because it answered so many questions and made it a better performance.

Well, here’s one for you. As you’ve noted, “Strings & Threads Suite” ends up at the dawn of bluegrass, Bill Monroe’s kind of waiting on the doorstep. So since you’re at the doorstep of bluegrass, is there a bluegrass album in your future as well?

Isbin: I know you’re sitting down, but wait’ll you hear this.

Is Chris Thile involved in the next answer?

Isbin: Yeah, I mean I’ve asked him. On my next album I definitely do want to work with Chris, and he said yes. It would be an album that would involve a number of different guests from different genres and styles. It’s funny that you’re here right now and you’re asking me this question. I just got a phone call, three days ago, from the Recordng Academy and they’ve asked if I would play on the pre-tel, which is the awards ceremony that takes place in the afternoon before the evening ceremony. Ninety-nine percent of the awards are given in the afternoon. It’s not broadcast live on television, but it will be streamed live on the Internet, so their idea was that I do a ninety-second solo, then I’m joined by a band of bluegrass musicians and we do a bluegrass number. Because bluegrass is one of the genres that hasn’t had much attention at the Grammys, so this way they’ll be able to do two things at once. It’s supposed to be an all-star cast of bluegrass musicians joining me. Now this will be yet again a new venture for me. I’ve been doing Brazilian music and samba stuff with Laurindo Almeida; jazz with Larry Coryell; rock with Steve Vai—we have a duo and he’s written for me. Bluegrass really was the next terrain I wanted to go to because I’ve always loved it. I didn’t expect that I would be making my debut that way; I thought maybe we could try it out in a coffee shop first, or something! I said I need a part and an MP3 to study because I don’t improvise!

You have commissioned more concerti than any other guitarist. You’ve said you’ve done this because repertoire for guitar was so scarce at one time. Has that changed for the better now?

Isbin: I think when you look at guitar and orchestra, that’s a pretty specialized field. I’m proud to have contributed ten new works in that realm and some of them are by really well regarded composers who have been able, by virtue of writing great pieces, to put the guitar more center stage in the mainstream world of music. John Corigliano, I’ve performed the concerto he wrote for me more than sixty times; the Chris Rouse concerto received a Grammy Award for Best Classical Composition [Ed. Note: Christopher Rouse, “Concert di Gaudi for Guitar and Orchestra,” from Ms. Isbin’s 2001 album, Sharon Isbin], I’ve done that more than fifty times. So a lot of major orchestras and conductors want to do these works with me, and that again helps the visibility of the instrument and also brings it to a new level and a new landscape.

On that point of the visibility of the instrument, again when you started your professional career the guitar was pretty much a second-class citizen in the classical world. You’ve since founded the guitar department at Juilliard, taught at the Aspen Music Festival. Has this had the effect of upgrading the guitar’s standing in the classical world?

Isbin: Absolutely. It’s a whole different game now, especially in this country. You’ll still find pockets where it’s rarely seen and rarely heard—like the New York Philharmonic concert I did in preparation for the recording, which is still the only recording they’ve ever done with guitar and that came out in 2005 [Rodrigo: Concierto de Aranjuez; Villa-Lobos: Concerto for guitar; Ponce: Concierto del sur, Sharon Isbin and the New York Philharmonic, conductor José Serebrier, released on Warner Classics.]. The summer before that was their first performance with a guitarist in almost thirty years. So it’s not an instrument that is as prominent as the violin or the piano in the classical world, but it is an instrument that is even more prominent because of its popularity in so many styles of music, from pop, rock, jazz, folk, bluegrass, and as a result it’s an instrument that can really bring in the young audience and followers from many schools of music.

What drew you to teaching?

Isbin: I’ve always enjoyed teaching, and I even was doing that when I was in high school. The first big platform I had was when Oscar Ghiglia, who was my teacher at the Aspen Music Festival for five summers, asked me when I was 15 to be his teaching assistant. And there I was, working with people who were twice my age. So it was a great chance to become even more aware of how things happen and how you become more analytical about others, and therefore you can be more self-reflective as well. And not having had a teacher after the age of 16, except for an occasional lesson with Segovia, or Julian Bream, or a summer session with Oscar Ghiglia, I was on my own. So I had to learn with a mirror and a tape recorder. And because I had to teach myself, teaching became very natural for me. I like the stimulation of that; I like working with really talented people, because it’s like, I suppose, having a child, which I don’t have, but it’s my substitute. You’re always awed by a sense of discovery and a sense of spontaneity and a vision of the world which is different from yours, because it’s a different being. I’ve been introduced to a lot of repertoire through my students, and it’s definitely a two-way street.

Do you teach year ‘round at Juilliard?

Isbin: It’s from September to the end of April. I take very few students, just a handful, because I don’t have much time, and I travel a lot and am free to do all the traveling I want. So I really hand pick the best of the best, and that’s why it’s such a great process for me. I’m really mentoring those kids—I have three students this year. The maximum I would ever take would be six.

Are you a stern taskmaster?

Isbin: Well, I’m nice about it in that I respect them and I expect a lot as well. I expect them to be exacting about their own work in a way that will make them better players and true professionals.

‘She became the music; she became Bach’—Sharon Isbin, speaking in Bach and Friends, a new documentary about Johann Sebastian Bach from Michael Lawrence Films, Sharon Isbin discusses working with and learning from her teacher, Rosalyn Tureck, one of the world’s foremost interpreters of Bach. Glenn Gould once cited Ms. Tureck as his only influence as a pianist. Ms. Tureck died on July 17, 2003, at age 89. This segment does not appear in the final film.In your own experience as a student, you had some great guitar teachers, but you’ve also said the one who had the most impact on you didn’t even play guitar.

Isbin: Right. Rosalyn Tureck.

What did you get from her that’s proven so valuable?

Isbin: Talk about a stern taskmaster, but I needed that. She has an extraordinary sense of discipline about her own work, and I went to her with a desire to learn how to play Bach on the guitar, because there was no one in the guitar world to turn to and she had devoted her entire life to studying Baroque performance and really gaining an insight into both the musical and technical aspects of what that meant in a way that no other musician had ever done since…Bach’s time, basically. So I’ve been very fortunate to have had a friendship with her for thirty years and to have had her as a mentor; did all the editions of all the Bach lute suites with her, recorded them and they’re all still available. So it’s something that certainly changed my life.

You’ve mentioned in other interviews that you’ve seen a few more female students in your classes—-

Isbin: They’re all Europeans.

But males still dominate.

Isbin: Yes.

Why haven’t young women been drawn more to classical guitar?

Isbin: It’s very simple in America to answer that question, because classical guitar doesn’t have the history and the tradition that it does in Europe, where it goes back to 17th and 18th Century Spain and Italy, and of course the lute times in England. But here it’s a newer thing and the people from my generation who came to study classical guitar started out as young rock players who heard a classical CD and thought, Oh, that’s cool. And shifted gears as teenagers. But how many young girls were playing rock guitar? Not so many. So I think that’s why in America, at least, it’s been mostly guys. My experience was growing up in Italy at the age of nine and having this very unusual circumstance that brought me to a master teacher. Wouldn’t have happened if I hadn’t been with my family there.

Do you think of yourself in any way as carrying the mantle for female classical guitarists? Because there really has not been one of your prominence since Ida Presti in the ‘40s, and that’s a long gap between her demise and your arrival on the scene.

Isbin: I mean I’m very gratified—and it happens to me many times—when women write to me or meet me after a concert and say how much I’ve inspired them to play the guitar. I’m delighted about that because it means I’m having some kind of impact. I think my focus has been so much on the instrument, taking that to a place where it would garner more acceptance, that the gender issue hasn’t been so much in my mind, but it certainly was, say, when I was a student at the Aspen Festival in the 1970s. And the summer that Oscar Ghiglia asked me to be his teaching assistant, it was because fifty students had shown up and he needed help. And how many of those fifty were female? Two. You couldn’t miss the point. But having had two older brothers, I always approached the idea of the challenge as something that would motivate me to be the best I could be.

Gender aside, you would be considered in the very top ranks of classical guitarists in the world, alongside the likes of David Russell, John Williams, Christopher Parkening, a handful of others. Do you have any contact with your contemporaries in the field?

Isbin: Oh, sure. It’s a fairly friendly lot. I think like any oppressed group we tend to band together and gain strength in numbers.

What’s next?

Isbin: What’s next is planning the next recording, and I’ll talk about that once it’s in the can. Chris Thile is certainly on my wish list of guests; talk about genius incarnate, that guy is amazing. He’s such a virtuoso technically, so flawless and such a perfectionist, but he’s also a marvelous musician, just the way he moves when he plays, I mean you want to be dancing in the aisles. Very special guy.

Rosalyn Tureck’s recordings are available at www.amazon.com

Sharon Isbin’s Journey to the New World is available at www.amazon.com

Sharon Isbin’s American Landscapes is available at www.amazon.com

Sharon Isbin’s Grammy winning collaboration with the New York Philharmonic—marking the first time the famed orchestra had recorded with a guitarist—is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024