J.D. Salinger Got His Ham

(January 1, 1919-January 27, 2009)

by David McGeeWhen the news brought word of the death of J.D. Salinger, my first thoughts turned not to Catcher In the Rye, or “A Perfect Day for Bananafish,” but to another towering literary figure, the late playwright August Wilson—specifically to one of Wilson’s characters, Hambone, in his Tony Award winning, Pulitzer Prize nominated play, Two Trains Running, then the seventh in what Wilson envisioned as a 10-part cycle of plays chronicling the black experience in 20th Century America. Hambone has one purpose in life: to be properly compensated for painting the fence of a white meat-shop owner years earlier. Promised a ham for his work, he was instead given a chicken. At the play’s start, nine and a half years have since passed, and every day Hambone has been showing up at the owner’s doorstep, shouting, “I want my ham! He gonna give me my ham!”

Hambone’s single-mindedness in pursuing justice seems not unlike Salinger’s self-imposed seclusion upon moving from Manhattan to Cornish, NH, in 1953, after The Catcher In the Rye and its attendant success and notoriety brought him unwanted personal fame. Though he was social in his early days in Cornish—even to the point of granting an interview with the daily paper’s high school page, which was the published in the editorial section, prompting him to cease contact the high school students he had befriended and even invited into his home for after-school gatherings—-he gradually withdrew altogether. Various accounts of his life tell of him embracing Kriya yoga and exploring all manner of alternative religions and medicines (he had an early interest in Dianetics, which became Scientology, but after meeting with founder L. Ron Hubbard he wanted nothing to do with it or Hubbard); of a tumultuous marriage that produced a son, Matthew, and a sickly daughter, Margaret; and one writing project after another left incomplete when he would go off on a tangent exploring yet another new religion or spiritual discipline. Margaret later published a memoir in which she charged her father with being abusive toward the other members of the family, which prompted son Matthew to issue a statement refuting every claim his sister had made. In 1972 the then-52-year-old Salinger began a year-long, live-in relationship with 18-year-old Yale student Joyce Maynard, which ended either because she wanted children and Salinger felt he was too old to be a father (as Salinger claimed to his daughter) or because he simply and abruptly dumped Maynard (her version). Maynard, though, insisted Salinger had two novels completed. Either because Maynard’s revelations had flushed him out or for some purpose that seemed useful to him, Salinger emerged briefly in 1974 to speak to a New York Times reporter and say: "There is a marvelous peace in not publishing ... I like to write. I love to write. But I write just for myself and my own pleasure.”

In the end, what happened behind the closed doors of Salinger’s personal life—and an untidy one it seems to be—may always be in dispute. And what relevance it has to those not engaged in Salinger scholarship is anyone’s guess—J.D. Salinger’s neuroses and demons are unlikely to compete with today’s tabloid fodder as water cooler chatter, and his sexual peccadilloes, if indeed there are any, pale compared to those of today’s headline makers (at least he was never running for President, entrusted by a State to its Governor’s seat, or a sports icon and presumed role model). But Salinger got his ham, as Hambone did his—he wanted to be left alone to write, “just for myself and my own pleasure,” and so he was.

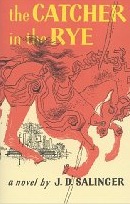

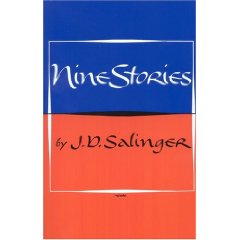

We have The Catcher in The Rye, Nine Stories, Franny and Zoey, and the novellas Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction. Immediately upon the author’s death speculation was rampant as to the volume of manuscripts lay complete and ready or publication in his study. His daughter, not the most reliable source, as it turns out, did offer one tantalizing tidbit about her father’s filing system for his unpublished manuscripts, writing: "A red mark meant, if I die before I finish my work, publish this 'as is,' blue meant publish but edit first, and so on." From his published work we have Holden Caulfield, Catcher’s scabrous, truth-seeking, first-person narrator, alienated and rebellious, railing against “phonies,” seeking some higher purpose—and, not incidental to his appeal, mentally unhinged. Inspired by an English teacher who speaks of the stronger man living humbly, rather than dying nobly, for a cause, Holden decides to go out west. But after his sister gets upset that he won’t take her with him, he decides to stay put; melancholic and metaphysically whipped, he finds an odd serenity, tinged with sadness, overcoming him as he watches his sister ride the Central Park carousel, in Catcher’s most beautifully crafted scene. At the book’s close, Holden speaks of returning to school, alludes to time spent in a mental hospital, and concludes, in essence, that for all his determined resistance to the regular routine of life, he’s in its grip, and so too may readers find themselves. On the other hand, Catcher has been the subject of so many interpretations and literary debates as to the meaning of its words and symbolic language that agreement on what Salinger really meant to say through Holden Caulfield remains one of literature’s most enduring arguments. In the end, an unnamed Amazon customer, noting in a gripper of a lead sentence, “This book caught me just as I was going over the edge,” may have summarized Holden’s, and Catcher’s, enduring appeal better than all the celebrated critics in the world by observing: “I think the reason that this book is so popular is because we are all crazy to some degree and those who criticize the book or dislike it are simply those who cannot accept that part of themselves. As long as there are humans on this earth this book will remain a classic.”

***

Justice To J.D. Salinger

One of the finest appraisals and defenses of J.D. Salinger came courtesy Janet Malcom, writing in the June 21, 2001, edition of The New York Review of Books. In “Justice To J.D. Salinger,” Ms. Malcolm, not noted for being kind to her subjects (writing in Salon in 2000, Craig Seligman said Malcolm “discovered her vocation in not-niceness…”), went far towards clearing the air about what was what with regard to Salinger and his critics; indeed, it seemed the zest of the vitriol being hurled Salinger’s way by some of the highest of highbrow critics incited in Ms. Malcolm a most spirited defense of the author in which she sorted out who was saying what and why (with particular attention being paid to what she felt were distortions and general misinterpretations of the critically assailed Franny and Zooey, which she asserts “is arguably Salinger’s masterpiece”), and even waded convincingly into the family dispute between the Salinger children. Below is an excerpt of her piece; the entire article can be accessed online at http://www.nybooks.com/articles/14272, and it’s well worth spending time with.

To Salinger fans, Malcolm offered the encouraging speculation that “there may be dozens, maybe hundreds, more Glass stories to read and reread,” and reminded us of Salinger’s own words, as published on the dust jacket of the 1961 Little, Brown edition of Franny and Zooey: “Both stories are early, critical entries in a narrative series I'm doing about a family of settlers in twentieth-century New York, the Glasses. It is a long-term project, patently an ambitious one, and there is a real-enough danger, I suppose, that sooner or later I'll bog down, perhaps disappear entirely, in my own methods, locutions, and mannerisms. On the whole, though, I'm very hopeful. I love working on these Glass stories, I've been waiting for them most of my life, and I think I have fairly decent, monomaniacal plans to finish them with due care and all-available skill.”

To which Malcolm added this optimistic postscript: “The image of the patiently and confidently ‘waiting’ writer is arresting, as is the term ‘settlers,’ with its connotations of uncharted territory and danger and hardship.”

Justice to J.D. Salinger

By Janet Malcolm

(The New York Review of Books, Volume 48, Number 10, June 21, 2001)

When J.D. Salinger's "Hapworth 26, 1924"—a very long and very strange story in the form of a letter from camp written by Seymour Glass when he was seven—appeared in The New Yorker in June 1965, it was greeted with unhappy, even embarrassed silence. It seemed to confirm the growing critical consensus that Salinger was going to hell in a handbasket. By the late Fifties, when the stories "Franny" and "Zooey" and "Raise High the Roof-Beam, Carpenters" were coming out in the magazine, Salinger was no longer the universally beloved author of The Catcher in the Rye; he was now the seriously annoying creator of the Glass family.

When "Franny" and "Zooey" appeared in book form in 1961, a flood of pent-up resentment was released. The critical reception—by, among others, Alfred Kazin, Mary McCarthy, Joan Didion, and John Updike—was more like a public birching than an ordinary occasion of failure to please. "Zooey" had already been pronounced "an interminable, an appallingly bad story," by Maxwell Geismar and "a piece of shapeless self-indulgence" by George Steiner. Now Alfred Kazin, in an essay sardonically entitled "J.D. Salinger: 'Everybody's Favorite,'" set forth the terms on which Salinger would be relegated to the margins of literature for doting on the "horribly precocious" Glasses. "I am sorry to have to use the word 'cute' in respect to Salinger," Kazin wrote, "but there is absolutely no other word that for me so accurately typifies the self-conscious charm and prankishness of his own writing and his extraordinary cherishing of his favorite Glass characters." McCarthy peevishly wrote: "Again the theme is the good people against the stupid phonies, and the good is still all in the family, like a family-owned 'closed' corporation.... Outside are the phonies, vainly signaling to be let in." And: "Why did [Seymour] kill himself? Because he had married a phony, whom he worshiped for her 'simplicity, her terrible honesty'?... Or because he had been lying, his author had been lying, and it was all terrible, and he was a fake?"

Didion dismissed Franny and Zooey as "finally spurious, and what makes it spurious is Salinger's tendency to flatter the essential triviality within each of his readers, his predilection for giving instructions for living. What gives the book its extremely potent appeal is precisely that it is self-help copy: it emerges finally as Positive Thinking for the upper middle classes, as Double Your Energy and Live Without Fatigue for Sarah Lawrence girls." Even kindly John Updike's sadism was aroused. He mocked Salinger for his rendering of a character who is "just one of the remote millions coarse and foolish enough to be born outside the Glass family," and charged Salinger with portraying the Glasses "not to particularize imaginary people but to instill in the reader a mood of blind worship, tinged with envy. Salinger loves the Glasses more than God loves them. He loves them too exclusively. Their invention has become a hermitage for him. He loves them to the detriment of artistic moderation. 'Zooey' is just too long."

Today "Zooey" does not seem too long, and is arguably Salinger's masterpiece. Rereading it and its companion piece "Franny" is no less rewarding than rereading The Great Gatsby. It remains brilliant and is in no essential sense dated. It is the contemporary criticism that has dated. Like the contemporary criticism of Olympia, for example, which jeered at Manet for his crude indecency, or that of War and Peace, which condescended to Tolstoy for the inept "shapelessness" of the novel, it now seems magnificently misguided. However—as T.J. Clark and Gary Saul Morson have shown in their respective exemplary studies of Manet and Tolstoy—negative contemporary criticism of a masterpiece can be helpful to later critics, acting as a kind of radar that picks up the ping of the work's originality. The "mistakes" and "excesses" that early critics complain of are often precisely the innovations that have given the work its power. (Evidently understanding this, Updike ended his review with this handsome concession: "When all reservations have been entered, in the correctly unctuous and apprehensive tone, about the direction [Salinger] has taken, it remains to acknowledge that it is a direction, and that the refusal to rest content, the willingness to risk excess on behalf of one's obsessions, is what distinguishes artists from entertainers, and what makes some artists adventurers on behalf of us all.")

In the case of Salinger's critics, it is their extraordinary rage against the Glasses that points us toward Salinger's innovations. I don't know of any other case where literary characters have aroused such animosity, and where a writer of fiction has been so severely censured for failing to understand the offensiveness of his creations. In fact, Salinger understood the offensiveness of his creations perfectly well. "Zooey"'s narrator, Buddy Glass, wryly cites the view of some of the listeners to the quiz show It's a Wise Child, on which all the Glass children had appeared in turn, "that the Glasses were a bunch of insufferably 'superior' little bastards that should have been drowned or gassed at birth." The seven-year-old letter-writer in "Hapworth" reports that "I have been trying like hell since our arrival to leave a wide margin for human ill-will, fear, jealousy, and gnawing dislike of the uncommonplace." Throughout the Glass stories—as well as in Catcher—Salinger presents his abnormal heroes in the context of the normal world's dislike and fear of them. These works are fables of otherness—versions of Kafka's "Metamorphosis." However, Salinger's design is not as easy to make out as Kafka's. His Gregor Samsas are not overtly disgusting and threatening; they have retained their human shape and speech and are even, in the case of Franny and Zooey, preternaturally good-looking. Nor is his vision unrelentingly tragic; it characteristically oscillates between the tragic and the comic. But with the possible exception of the older daughter, Boo Boo, who grew up to become a suburban wife and mother, none of the Glass children is able to live comfortably in the world. They are out of place. They might as well be large insects. The critics' aversion points us toward their underlying freakishness, and toward Salinger's own literary deviance and irony.

Salinger's own perilous journey away from the world has brought many misfortunes down on his head. His modest wish for privacy was perceived as a provocation, and met with hostility much like the hostility toward the Glasses. Eventually it offered an irresistible opportunity for commercial exploitation. The pain caused Salinger by the crass, vengeful memoirs of, respectively, his former girlfriend, Joyce Maynard, and his daughter, Margaret, may be imagined. A redeeming moment occurred a few weeks after the publication of the latter book, when a letter by, of all people, Margaret's younger brother, Matt, an actor who lives in New York, appeared in The New York Observer. He was writing to object to his sister's book. "I would hate to think I were responsible for her book selling one single extra copy, but I am also unable not to plant a small flag of protest over what she has done, and much of what she has to say." Matt went on to write of his sister's "troubled mind" and of the "gothic tales of our supposed childhood" she had liked to tell and that he had not challenged because he thought they had therapeutic value for her. He continued:

Of course, I can't say with any authority that she is consciously making anything up. I just know that I grew up in a very different house, with two very different parents from those my sister describes. I do not remember even one instance of my mother hitting either my sister or me. Not one. Nor do I remember any instance of my father "abusing" my mother in any way whatsoever. The only sometimes frightening presence I remember in the house, in fact, was my sister (the same person who in her book self-servingly casts herself as my benign protector)! She remembers a father who couldn't "tie his own shoe-laces" and I remember a man who helped me learn how to tie mine, and even—specifically—how to close off the end of a lace again once the plastic had worn away.

What is astonishing, almost eerie about the letter, is the sound that comes out of it—the singular and instantly recognizable sound of Salinger, which we haven't heard for nearly forty years (and to which the daughter's heavy drone could not be more unrelated). Whether Salinger is the rat his girlfriend and daughter say he is will endlessly occupy his well-paid biographers, and cannot change anything in his art. The breaking of ranks in Salinger's actual family only underscores the unbreakable solidarity of his imaginary one. "At least you know there won't be any goddam ulterior motives in this madhouse," Zooey tells Franny. "Whatever we are, we're not fishy, buddy." "Close on the heels of kindness, originality is one of the most thrilling things in the world, also the most rare!" Seymour writes in "Hapworth." What is thrilling about that sentence is, of course, the order in which kindness and originality are put. And what makes reading Salinger such a consistently bracing experience is our sense of always being in the presence of something that—whatever it is—isn't fishy.

The Young Salinger, In His Own Words

(from STORY magazine, #25, November-December 1944)

‘I’m twenty-five…’

"I'm twenty-five, was born in New York, am now in Germany with the Army. I used to go pretty steady with the big city, but I find that my memory is slipping since I've been in the Army. Have forgotten bars and streets and buses and faces; am more inclined, in retrospect, to get my New York out of the American Indian Room of the Museum of Natural History, where I used to drop my marbles all over the floor. . . . I went to three colleges—never quite, technically, getting past the freshman year. Spent a year in Europe when I was eighteen and nineteen, most of the time in Vienna. . . . I was supposed to apprentice myself to the Polish ham business. . . They finally dragged me off to Bydgoszcz for a couple of months, where I slaughtered pigs, wagoned through the snow with the big slaughter-master, who was determined to entertain me by firing his shotgun at sparrows, light bulbs, fellow employees. Came back to America and tried college for half a semester, but quit like a quitter. Studied and wrote short stories in Whit Burnett's group at Columbia. He published my first piece in his magazine, STORY. Been writing ever since, hitting some of the bigger magazines, most of the little ones. Am still writing whenever I can find the time and an unoccupied foxhole."(Mr. Salinger modestly withholds an extremely interesting and without precedent bit of information from his biography, to wit, he recently sent a check of $200 from the battle front to STORY representing part of his earnings from some of his recent writing for large-circulation magazines. He said he wished this to be used by STORY for the encouragement of other writers and would like it to be applied, if that was feasible, to STORY's nationwide short story contests among the students of universities throughout the country. -Editor's note.)

‘I am twenty-six…”

J.D. Salinger, “Backstage with Esquire,” Esquire. October 24, 1945. p.34.

"I am twenty-six and in my fourth year in the Army. I’ve been overseas seventeen months so far. Landed on Utah Beach on D-Day with the Fourth Division and was with the 12th Infantry of the Fourth until the end of the war here. The Air Corps background for ‘This Sandwich Has No Mayonnaise’ comes naturally because I used to be in the Air Corps. Am also a graduate of Valley Forge Military Academy. After the war I plan to enlist in a good, established chorus line. This is the life.“I’ve been writing short stories since I was fifteen. I have trouble writing simply and naturally. My mind is stocked with some black neckties, and though I’m throwing them out as fast as I can find them, there will always be a few left over. I am a dash man and not a miler, and it is probable that I will never write a novel. So far the novels of this war have had too much of the strength, maturity and craftsmanship critics are looking for, and too little of the glorious imperfections which teeter and fall off the best minds. The men who have been in this war deserve some sort of trembling melody rendered without embarrassment or regret. I’ll watch for that book."

Buy Catcher In the Rye at www.amazon.com

Buy Nine Stories at www.amazon.com

Buy Franny and Zooey at www.amazon.com

Buy Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024