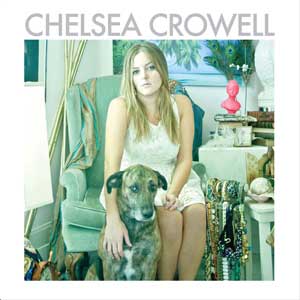

Chelsea Crowell: ‘I’m really grateful for what my mother and father have taught me, but most of what they’ve taught me or what I’ve retained has been by their example. I don’t really seek their advice.’ Photo: James Green

Artists On the Verge 2010

What, Indeed, Is In a Name?

Chelsea Crowell Stands On Her Own

By David McGeeWhen speaking with Chelsea Crowell the question of heritage is never far from the surface. How could it be, when she is the firstborn daughter of two of the most important songwriters of the past half-century, in her mother, Rosanne Cash, and father, Rodney Crowell. Mom has done nothing less than fashion a compelling and singular artistic voice out of country, pop, and rock ‘n’ roll influences, never going in any predictable direction and blessed with unerring vocal instincts that add extra heft to her penetrating lyrics. Dad has done nothing less than to elevate the Texas singer-songwriter tradition to a new artistic plateau of eloquence and insight, while fusing its folk and hard country roots to Beatles-ish rock ‘n’ roll. Grandpa, by the way, was Johnny Cash. Okay?

Rosanne and Rodney’s daughter, though, takes as hard left away from their music as did Holly Williams on her scintillating debut, The Ones We Never Knew. Like Ms. Williams, daughter of Hank Jr., granddaughter of Hank Sr., Ms. Crowell doesn’t attempt to break the mold so much as recast it in her own terms to a point where the bloodlines disappear into the art, rendering comparisons to other family members’ work an almost fruitless endeavor, save for each one’s facility with the tools of their trade—principally words, first and foremost, and then the proper casting of those words into an environment that enlarges their impact, deepens their meaning, and brings their truth to the surface. Like Ms. Williams’s, though, Ms. Crowell’s original songs do betray a spiritual shout-out to one Marlene Dietrich, who famously sang, “Good for nothing/Men are good for nothing.” Which is to say that the male of the species gets a working over here and there on Chelsea Crowell.

‘I can be playing live now and start thinking, Oh, gosh, I hope there’s not somebody out there that’s just come to see so-and-so’s granddaughter and how will I measure up. On a bad day you can think of all sorts of things like that; on the usual good days, no.’But there’s more than payback going on, a lot more. Chelsea Crowell is also a work of vivid lyricism, daring presentations, and a focused artistic vision refusing to be hemmed in by genre or heritage in its search for full expression, using all available tools—sometimes literally—to construct an environment suited to enhance stories that don’t always flow from beginning to middle to end, but rather drift off into ambiguous conclusions for the listener to puzzle out. Making the arrangements a character unto themselves allows Ms. Crowell, in many instances, to step back more into the role of reporter than protagonist, as the music carries the weight of the songs’ emotions. It’s a tricky maneuver, but the artist, who co-produced the disc with her musical collaborator/inamorato Loney John Hutchins, pulls it off seamlessly, much as Ms. Williams did before her, and Tom Waits and Leonard Cohen before them.

“I guess when I first started experimenting in the studio I thought, Oh, my God, there’s too many options with music,” Ms. Crowell said recently from her home in Nashville. “If anything that’s the most intimidating part to me—how am I ever going to be able to tap into the best thing that’s for this song lyrically? The lyrics come easy, and then it’s trying to pick out the best thing possible in choosing a pairing, an arrangement, for the lyrics, but there’s just an endless supply of things out there to choose from. By the time I got close to finishing the record I was better at realizing that less is more. If (the arrangement) could just kind of be interesting and yet help carry a lyric and have arrangements open things in their own way and be interesting on their own, well, life goes on and happens around music.”

Life certainly goes on and happens around this music. “Famous” has strains of traditional country and gospel in its melody, and a twangy guitar line as muscular as Duane Eddy’s, as abject as Phil Upchurch’s solo in Dee Clark’s “Raindrops.” “Heart’s Mistakes” rides on a wave of clattering drums and pulsating, twangy guitar, with whimsical Rhodes fills adding the slightest touch of levity; in a breakup song like no other, “Never Be a Beggar,” drums gallop ceaselessly through the soundscape and carry the song forward until it explodes in howling, surging backwards guitar loops, a swelling rush of organ and twangy guitar until fading into the austere, ethereal “The Run,” tellingly a woman’s declaration of independence—one fully recovered from the blow described in “Never Be a Beggar”—but delivered in a detached, ghostly whisper over a foreboding soundscape notable mostly for the Ennio Morricone Days of Heaven piano run flittering eerily through it and wobbly, theremin-like punctuations here and there. In “Sometimes Love,” Ms. Crowell, playing gut-string guitar, sings in stark relief over her two-string riff, upbraiding either her paramour or husband (that it could be either is another hallmark of her writing—the album’s opening song, the shambling, percussive “Tremelo Trees,” struck this listener as being concerned with Jesus and Mary Magdalene, but Ms. Crowell avers to the contrary, saying it’s about the sun and the moon, “but now I want to go write a song about Jesus and Mary Magdalene.”), and the same two-string riff recurs near the end, in the kissoff ballad, “Eddie Brown,” where it’s buttressed by a sinister, humming organ. Set in the Civil War and describing the frustrations of a Southern woman impatient with (to the point of being frazzled by) her side’s sinking fortunes, “Where the Hell Is Robert E. Lee” is the album’s one, glorious rocking moment, complete with ebullient horns and a positively infectious drive about it, plus, if you listen closely, intimate, beautifully sketched details about a family’s travails as the War approaches their front door. It’s a magnificent, complex and fully realized character study, replete with large dollops of anguish and morbid wit (so much of the latter in fact, that it meets the novelist Dawn Powell’s definition of true wit with dead-on accuracy: “True wit should break a wise man’s heart. It should strike at the exact point of weakness and it should scar. It should rest on a pillar of truth and not on a gelatin base, and the truth is not so shameful that it cannot be recorded.”) Not least of all, there is “Someday,” which softly fades in after “Robert E. Lee” departs, and jump-cuts to an early ‘60s pop influence in its melody and heartbeat rhythm, its yearning enhanced by Crowell’s drawling, soft vocal.

If there is anything about the album directly reflecting her lineage, it would be certain Chelsea lyrics that leap out as being Rodney- or Rosanne-like: “How long has yesterday been” in “Tremelo Trees”; “I’d love to whisper nothing sweet as Heaven/but I’ve lost the heart to lay on the line” in “I Want My Seven Years Back”; “You always remain where the sun never sets/I always return from how far I get” in “Lost Aimless Beauty.” But that’s nothing intentional; it comes with the territory, you might say. For her part, Ms. Crowell is undaunted by her heritage, but also conscious of it in a refracted way.

‘I always thought that my grandpa was, for lack of a better word, bad-ass enough that I could relate to him. It wasn’t like having Frank Sinatra or something for your grandfather.’“You know, there’s so many parts to it,” she says, “There’s the Carter Family; then there’s my grandfather, who seemed like a larger than life character; and then I have my immediate father and mother. Then like June’s daughter Carlene Carter was married to Nick Lowe, so there are all sorts of little avenues here and there. I don’t know, I think that maybe it wasn’t so intimidating because there were so many different relatable things going on. I always thought that my grandpa was, for lack of a better word, bad-ass enough that I could relate to him. It wasn’t like having Frank Sinatra or something for your grandfather. I don’t know about being intimidated. Maybe when it comes to live performances. I can be playing live now and start thinking, Oh, gosh, I hope there’s not somebody out there that’s just come to see so-and-so’s granddaughter and how will I measure up. On a bad day you can think of all sorts of things like that; on the usual good days, no.”

At 27 (28 on January 25), Ms. Crowell is a bit more mature than many newcomers to the business. Born in Nashville, she spent part of her formative years in New York City with her mother; attended boarding school in Maryland; moved to Colorado to work in equine therapy for some four months (equine therapy is physical therapy for disabled children that involves them riding what Ms. Crowell calls “gentle-natured horses,” adding, “it’s a good bonding experience for kids with autism or any number of disabilities. They get to bond with an animal.”); returned to New York; matriculated to the Memphis College of Art; and wound up in Charleston, South Carolina, where, at age 19, she wrote a novel and promptly burned it.

“It wasn’t very good,” she says of the novel. “I’ve got bits and pieces of it. It was about a hundred pages long. It was my attempt at writing some…I don’t know, some romantic…I’m trying to think what I was reading at the time—like Milan Kundera, something like that. And I thought, I can do this. But I couldn’t.”

Still, the revelation of the novel’s existence (however brief it was) is interesting because Ms. Crowell’s lyrics have such a strong literary quality—in most instances they flow like lyrical prose more so than song lyrics. She cites Leonard Cohen and Guy Clark as “my heroes of songwriting that I always wish I was,” but confirms that “I am a reader, and I was an English major in college. I’m sitting at my desk now staring at a copy of One Hundred Years of Solitude. For my fifteenth birthday I asked my mom for a copy of Anna Karenina. She wrote on the inside flap, ‘I always dreamed I would have a daughter that would ask me for this book.’”

Music came along at a young age, and quickly departed. At “12 or 13,” she learned to play guitar, inspired by “the Sex Pistols, the Misfits, a lot of punk bands.” But she didn’t pursue it, and didn’t pick up the guitar again until she moved back to Nashville and formed a band, Jane Only, when she was 19 (Jane is her middle name), which disbanded six years later, when Chelsea was 25. Jane Only recorded extensively, but its first album will not be seeing the light of day until February, when Chelsea releases some of its work on CD. Compared to her solo debut, Jane Only is, she says, “much more raw rock ‘n’ roll, lots of electric guitar. My co-collaborator, Stephen Braren, is a great guitar player, has a dark, brooding, Dick Dale thing going on for him as far as guitar playing goes. I really like it; it’s a lot of fun. Not as vulnerable or naked, so it’s a lot more fun to play.”

Chelsea Crowell (left) with Stephen Braren in the Jane Only days, 2006

Photo: Pierette AbeggChelsea Crowell, the album, began in 2008 in the wake of Jane Only’s breakup (the band’s MySpace page says “All five band members live in Tennessee. It is the one and only thing they agree on.”), but it was only intended to be, in Chelsea’s words, “an experiment.” In the middle of a particular night she was tossing and turning, unable to sleep, got up and wrote the song “In Your Arms Again.” Wrote it “in about 25 minutes,” then fell fast asleep. Upon waking, she played it through and decided it would be the centerpiece of an EP. Then she called Loney John Hutchins and asked, “How do you do this without a band?”

“We recorded it as the beginning of an EP,” she says. “Then I had three more albums’ worth of material and said, ‘Let’s just go ahead and go the distance. Let’s make a record, I’ve got all the stuff here.’ I don’t think I really thought I could do it. Not that I didn’t believe in myself, but I just didn’t think of it as an option.”

Like the entire project itself, the striking, surprising arrangements are the product of “pure experimentation. Just lots and lots of trying different things, from setting up little amps in the bathtub, wiring a microphone into the bathroom where the amp was coming out of to putting a capo on a bass, playing a 12-string guitar through a Fisher-Price recorder thing. A lot of these things were unnecessary and actually sound pretentious in a way—‘Oh, I did this the coolest possible way’—but it was a really good learning experience for me. Now I know in the future I don’t need all the things but I know they’re there, should I say, ‘You know what would really sound good here?’ All of those sounds are really just from experiments.”

However much she makes her album sound like an accident that came out exactly right, Ms. Crowell admits to taking great care in the songs’ sequencing, an art unto itself that both her father and mother, to name two, have utterly mastered. That alternating bass-string riff we hear a couple of times? It’s critical to the album’s rising and falling tension owing to where those songs occur in the tunestack, just as “Where the Hell Is Robert E. Lee,” coming late in the sequence, has the feel of a reverie, a much needed one at that.

“I have an attention to detail for stuff like that,” Ms. Crowell admits. “I don’t know if it works for everybody that’s listened to it, but it sure works for me as far as the sequencing goes. It’s not about just alternating fast and slow songs—those naked, bare songs are a break from the others. That sequencing, I thought it over for awhile.”

Chelsea Crowell and father Rodney performing together in a benefit performance at Nashville’s Radio Café. ‘I was 22 at the time and had absolutely no idea what I was doing, was scared out of my mind,’ Chelsea says.Asked if she ran any of the material by her parents either beforehand or after the record was completed, she states, unequivocally, “No,” and the whole bloodline angle rears its head again. But if you knew Chelsea Crowell, you would know she would not seek mom’s and dad’s approval or necessarily even counsel when it comes to music.

“Not because there is any ill will or because I was trying to be—I’m not really sure why—I’m still that way, too,” she says in trying to explain the relationship. “I asked my dad to sing with me on ‘I Want My Seven Years Back’ because I thought it would be a really cool thing to do and that was after the whole thing was recorded and we were putting some finishing touches on it. I don’t know how to answer that; they’ve influenced me because I’ve been listening to their music my whole life and I really respect both of them as gifted songwriters. I’m really grateful for what they’ve taught me, but most of what they’ve taught me or what I’ve retained has been by their example. I don’t really seek their advice. I think that’s just my personality anyway; that’s just who I am.”

For her part, mother Rosanne told the Toronto Sun that her daughter’s album made her realize how music and songwriting comprise “an ongoing story” in the Cash family, adding: “It’s not just me following my dad; this goes back a long way, and hopefully will go forward.” In an email with this writer she reiterated and expanded upon those sentiments:

“I didn't even know Chelsea was a songwriter until she had nearly finished writing a record. She plays it very close to the vest, but that's how she's always been. I respect her. I would never force my opinions or advice on her. I'm in awe of her, and not just a little. I could never have written something as cinematic, or as singular to time and place, with such a sophisticated chord progression, as ‘Where The Hell Is Robert E. Lee?’ I don't know that I could do it now, after 35 years as a songwriter. She is a bit of a savant. And I know she imagined the bulk of the arrangements and soundscapes, as well as writing the songs. I'm so deeply proud of her, and I feel a tremendous relief in knowing that she is as great a songwriter and musician as she is. It makes me feel that I don't have to work so hard; our family profession will continue, refined to the degree of another generation.”

Of daughter Chelsea Crowell, Rosanne Cash says: ‘I feel a tremendous relief in knowing that she is as great a songwriter and musician as she is. It makes me feel that I don't have to work so hard; our family profession will continue, refined to the degree of another generation.’Also responding via email, father Rodney was typically insightful, self deprecating and laudatory all at once: “Of course I'm proud of Chelsea in that shameless ‘my kid is a freakin' genius’ way that we baby boomers tend to operate. We don't really embrace ‘run of the mill’ readily do we? Of course I am wont to see myself in my daughter. But in the case of Chelsea, as a poet, it's my fear that she has eclipsed me altogether. I begged her to go to college and get a regular job. Good thing she has a mind of her own, huh?”

Now Ms. Crowell awaits the next step: finishing “this weird, strange country rock opera that I’ve been working on, and maybe by late spring set up a small tour in the U.S,” a prospect that both excites and frightens her, because “I still get really, really nervous beforehand. It’s hard for me. It’s hard to get on stage. My mom basically said, in so many words, not too long ago, ‘You might want to make sure it’s not just your garden variety stage fright that everyone else has.’ I thought then maybe I’m not any more special than any other person who gets scared to put themselves out there in front of a large group of people and be the center of attention and have them judge what you’re doing. I’m trying to come to terms with the fact that it makes you nervous. I’m too old at this point to be saying, ‘Oh, I’m not talented.’ I know where my talents are; the thing that comes most naturally is the writing and trying to pick out different musical arrangements; but certainly I cannot for the life of me imagine putting on the shows that even my mom puts on. That level of energy, maybe one day I’ll have it, but I can’t imagine having it now. And just being able to let yourself go like that. It requires so much.”

Somehow, you think it’ll all work out. Something about it being in the blood…

Buy Chelsea Crowell at www.amazon.com

Visit Jane Only’s MySpace page: http://www.myspace.com/chelseajaneandthegrammyawardwinners

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024