A Date With Elvis

The Hillbilly Cat would have been 75 this month. Who was he, whom do we say he was, and what did he bequeath us?Reflections by David McGee

So here we are. Elvis would have been 75 years old on January 8, had he lived to see 2010. As this is written near the end of 2009, your faithful friend and correspondent is steeling himself for the expected onslaught of mainstream media speculation concerning the course of Elvis’s life were he still with us, most of it sure to be as ill-informed and shallow as it will be irrelevant to the artist’s work. Somewhere there is sure to be a debate spurred by the spurious, fact-free charge by dim bulb Chuck D. and his equally dim-bulb acolyte Mary J. Blige as to whether Elvis was a racist, even after the author of Elvis’s definitive biography, Peter Guralnick, would seem to have laid those charges to rest in his typically eloquent, graceful fashion in an August 13, 2007 New York Times Op-Ed piece, “How Did Elvis Get Turned Into a Racist?” (http://www.elvis.com.au/presley/peter_guralnick_elvis_racist.shtml)

Guralnick points out that Mr. D “has long since repudiated that view for a more nuanced one of cultural history,” in which the latter wonders, “what does it mean for Elvis to be hailed as ‘king,’ if Elvis’s enthronement obscures the striving, the aspirations and achievements of so many others who provided him with inspiration?” However, the forces responsible for obscuring the paths of black artists who influenced Elvis were at work long before Elvis showed up, and got busier after he arrived. Maybe the more interesting question is why the door to white America’s acceptance of black artists, which was kicked open in the late ‘20s and ‘30s by Duke Ellington, when he made his groundbreaking tours of the south under the aegis of his manager/publisher/booking agent/collaborator Irving Mills—a white man, Jewish no less—closed again for so long, until Elvis exploded them off their hinges for good. In an article on Elvis and race written by Christopher Blank and posted at www.elvis.com, the late Isaac Hayes offers a balanced perspective that Mr. D and others have since adopted: “Elvis was due the respect he had. No animosity. No sour grapes. Elvis was the man. The thing was that we didn’t get what we (black artists) deserved. Ignorance is one of the main things. Racism? It’s one of the factors. I would say it took the whole world outside of Memphis to recognize what a treasure black Memphis had.” In the same article, Rufus Thomas, who would tell anyone within earshot how Sun Records’ owner Sam Phillips seem to lose interest in him and all his other black artists after Elvis came along, took an even longer view than did Isaac Hayes: “Well, a lot of people said Elvis stole our music. Stole the black man’s music. The black man, white man, has got no music of their own. Music belongs to the universe.” Nothing about Elvis and race is going to be settled in TheBluegrassSpecial.com, but Blank’s article is well worth reading for a balanced perspective not only of Elvis as he’s regarded by his contemporaries but also as he’s seen by hip-hop and rap artists who have no memory of Elvis as a living human being. Suffice it to say, Chuck D does express a “more nuanced” opinion of Elvis as a result of hosting a Fox TV special on Graceland from the black perspective, but Ms. Blige appears to be a terminally hopeless Presley naysayer. And with so many barbs being hurled at Elvis for the “King” monicker, let’s state for the record that Elvis never referred to himself as royalty, and never asked to be called the King of anything or requested others do so, in contrast to a recently deceased King of Pop. (Christopher Blank’s article is posted at http://www.elvis.com.au/presley/elvis_not_racist.shtml)

There will be speculation as to what a 75-year-old Elvis would look like, which is simply impossible for those of a certain generation even to contemplate. In the interview accompanying these musings, Ernst Jorgensen, the world’s premier Elvis historian/researcher, answers a simple “NO!” to the question as to whether he can imagine Elvis at 75. Surely illustrations of the elder Elvis will find their way into print. But who cares? He was dead at 42. We hear he dyed his hair right up to the end, but we haven’t seen his real hair color since the early ‘50s anyway. Who cares?

We are also reaching a point in time when the Elvis literature, heretofore a growth industry, is beginning to wane. Peter Guralnick’s thoroughly researched, beautifully crafted two-volume biography of Elvis, Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley and Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley, pretty much obviates the need for any more biographies, and Ernst Jorgensen is busy on a new book that will document Elvis’s life and movements pre-RCA (his research has already turned up an apparent discrepancy between the date when Carl Perkins, whose biography was written by yours truly, first met Elvis, and the actual date of the show Perkins claims to have attended to get his initial look at the artist whose debut Sun single, “That’s All Right” b/w “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” was in the style of the music the Perkins Brothers Band had been playing around West Tennessee for several years already—look for a correction in the digital edition of Go, Cat, Go! The Life and Times of Carl Perkins, The King of Rockabilly.) The Elvis.com site lists several books either in progress or having been published in 2009, but these are mostly documenting the dates of Elvis’s live performances or insider accounts of specific sessions, books of photographs and portraits, even a fashion book featuring punchout cardboard images of Elvis (Elvis: Your Personal Fashion Consultant), and memoirs of supposed friends and fans. By far the most ambitious and most notable of these is a dubious tome by a good writer, Alanna Nash, about Elvis’s private love life, Baby, Let’s Play House: Elvis Presley and the Women Who Loved Him, which has as its animating concept an investigation into why Elvis, with so many women available to him, was unable to maintain a lasting romantic and sexual relationship with any of them. Unfortunately, there’s a little too much monkey business going on between the covers of Baby, Let’s Play House—questionable psycho-historical presumptions, as well as psychobabble, dicey sources, some overwrought prose…you get the picture. Still, future generations of Elvis scholars will have to deal with Ms. Nash’s book, for better or worse, but in its own time it may fall into the growing category of TMI, along with the expanding list of Tiger Woods’s many birdies. With regard to Elvis and women, the key to understanding his bed-hopping style may be better explained in a book that would seem to have nothing to do with Elvis at all, but in fact has a passage that might have been spoken by any enormously gifted, driven artist riddled with personal insecurities, as Elvis most certainly was.

As Lita Gray, 12-year-old Lillita Louise MacMurray was cast as the Flirtatious Angel in Charlie Chaplin’s classic 1921 silent film, The Kid; at 16 she was pregnant by the 35-year-old Chaplin and, after refusing a cash offer of $20,000 to wed another man, became his wife in a secret ceremony held in Mexico. Their three-year marriage was tumultuous and epically unhappy, producing two sons but ending in a bitter, headline-making divorce that found the court awarding her a then-record $600,000 settlement from her husband. Years later, after an unsuccessful attempt to establish herself as a nightclub entertainer, two more failed marriages, a constant battle with alcoholism and several electroshock treatments while confined to a sanitarium, she sought Chaplin’s counsel at a moment when she was nearly paralyzed by depression. Chaplin, then newly wed to the woman who would be the love of his life, Oona O’Neill, daughter of playwright Eugene O’Neil, took his former child bride for a long drive, and, after giving her the pep talk she was hoping for, confessed to his monstrous behavior during their marriage. (This, now, is by her account; in his own, sanitized autobiography, Chaplin declines to discuss Lita Gray Chaplin, out of respect for the feelings of their children.) Omit his references to his physical characteristics, and it might well be Elvis Presley explaining his own wandering ways.

“I didn’t understand myself,” Chaplin told Lita. “All I knew was that I was always afraid of people, afraid to be hurt. I couldn’t ever quite believe that anyone could love me. I was sensitive about being a small man with an oversized head and such small hands and feet. I never understood women. I mistrusted them. When they got too close I conquered them, but I couldn’t love them for long because I was convinced they couldn’t love me. Fantastic, isn’t it? But there’s the secret story of the self-assured Charlie Chaplin.” (p. 314, My Life with Charlie Chaplin: An Intimate Memoir by Lita Gray Chaplin with Morton Cooper; Bernard Geiss Associates, 1966; it should be noted that Lita Gray Chaplin later disowned this memoir as mostly fabrication by her collaborator when she published a second memoir, Wife Of the Life Of the Party, shortly before her death in 1995.)

Again, overlook Chaplin’s physical description of himself and it might as well be Elvis Presley talking. Those who have no interest in hearing more about Elvis’s love life but would like some key to unlocking the mystery of his relationships to women in his life are advised to get lost in the first great book about Elvis, Elvis and Gladys, by Elaine Dundy, originally published in 1985. Dundy’s thoughtful, meticulously researched exploration into the complexities of the mother-son relationship remains the most thorough and enlightening look at the Presley lineage, and was the first book to examine the Smith family’s (Gladys’s line) genetic predisposition to certain illnesses that eventually afflicted Elvis and sent him hurtling towards his sad decline and death. Moreover, it unflinchingly, and without sensationalism, examines the nature of Elvis’s love for his mother and how her death shadowed him the rest of his life, affecting not only his relations with other women but his entire outlook on spirituality, the afterlife, sin and redemption, and in this way provides the missing context for the excesses and obsessions of his later years, courtesy a writer who came to the project not as a music critic or slavish Elvis fan, but rather as a best selling novelist (The Dud Avocado, 1958) and wife of the celebrated film critic Kenneth Tynan. Included in this issue is the late Ms. Dundy’s (she died in 2008) reminiscence about the origins of her interest in Elvis and Gladys.

But mostly we are here to celebrate what we know of Elvis without qualification: he was a great artist, for reasons beyond the depth of his best performances, but it’s those performances that speak most profoundly to the general populace and which are the focus of another superb box set from the good folks at Legacy Recordings, Elvis 75: Good Rockin’ Tonight. Produced by Ernst Jorgensen, with a first-rate Elvis liner essay by Billy Altman (contributing editor to TheBluegrassSpecial.com, Huffington Post blogger and author of a fine biography of humorist Robert Benchley, Laughter’s Gentle Soul: The Life of Robert Benchley), who actually manages to find something new to say about Elvis’s recorded legacy, the box set encompasses four CDs containing 100 songs. The first two discs are dominated by the monumental chart hits of the ‘50s and ‘60s (including the Sun tracks that were licensed to RCA and appeared on the albums A Date with Elvis and For LP Fans Only, as well as Elvis’s self-financed acetate of “My Happiness” recorded at the Sun studio [then the Memphis Recording Service] in 1953 as a gift for his mother). You might say we’ve heard it all before, and we have—what’s interesting is how fresh and urgent it remains, a half-century-plus later.

From the movie This Is Elvis, the recording session for the original version of ‘Always On My Mind.’ These vintage images will take you back. Nice try, Willie. This version is included on the Elvis 75: Good Rockin’ Tonight box set.Discs 3 and 4 contain a fair share of hits too, but are more focused on the dedicated Elvis fan’s Holy Grail—the “deep cuts,” amazing performances buried on albums as non-single tracks, or as bonus tracks on soundtrack albums, as well as live recordings never released as singles. Back in 1991 RCA released an entire LP of such songs, titled The Lost Album, which, apart from the stolid “Blue River,” was nothing less than a clinic in masterful interpretive singing. Three cuts from that album are on Disc 3, the top 10 single “(You’re) The Devil in Disguise,” the obscure Doc Pomus-Mort Shuman gem, “(It’s A) Long, Lonely Highway” (from the Kissin’ Cousins soundtrack album) and the wistful “It Hurts Me” (a top 30 hit), but you’ll have to find the album itself (it goes for $250 new at Amazon) to hear gems such as the mesmerizing, existential beauty “What Now, What Next, Where To?,” the tender billet doux “Never Ending,” and the haunting “Echoes of Love.” Elvis, like Sinatra before him, made an art of the Christmas song, but only “Blue Christmas," among his two albums’ worth of Yuletide outpourings, is offered in the new collection; and one of the greatest gospel singers of all time is represented but twice, with “(There’ll Be) Peace In the Valley” and “How Great Thou Art,” predictable choices both. Choices had to be made, however, and on that count Jorgensen has done laudable work, as usual. Not only are the great rock ‘n’ roll songwriters well represented (Disc 3 is practically a tribute to the hip, durable work of the Doc Pomus-Mort Shuman team), but Jorgensen’s decisions reveal his fine-tuned Elvis sensibility: “Judy,” a great cut from 1961, and one of the few songs Elvis recorded actually titled with a female name; the fierce blues of “Reconsider Baby”; the live, and most moving version of “An American Trilogy,” from the eight-LP Elvis Aaron Presley collection; three tracks—“The Fool,” a wrenching take on Willie Nelson’s “Funny How Time Slips Away” and a red-hot, horn-fueled, extended reimagining of “I Washed My Hands In Muddy Water”—from the hallowed ground of 1970’s Elvis Country album; the graceful, longing yet oddly gentle agonizing he brings to Tom Jans’s “Loving Arms,” from 1974’s overlooked Good Times album; and of course, not least of all, from the almost totally disregarded, available-only-as-an-import Spinout soundtrack, the lone Dylan song Elvis ever covered, “Tomorrow Is a Long Time,” in a performance so probing, so ruminative, so interior that even Dylan himself sings its praises, as well he should.

So here we are. What would Elvis have been like at 75? We have no clue, really no clue. He died so young, at 42, leaving not the barest hint of where he might have taken his art, had he been able to heal himself of his physical and spiritual woes. We are bequeathed a body of work spanning only 23 years—hardly insubstantial but short by more than half of the recorded oeuvres of, say, Louis Armstrong and Frank Sinatra. But his voice reaches out to us, whether from 1954 or in his gripping, deeply conflicted reading of “Unchained Melody” recorded live in April 1977 in Ann Arbor, when you hear it in full flight, strong and yet vulnerable, oh so human in all its contradictions and frailties but beseeching us to soldier on, to believe, to live for a better day, even as his own body was betraying him, and he it. In the end we may have no good answers as to who Elvis really was—and we have made him out to be many things without granting him his humanity—but we have the music.

In closing, a personal confession: in 1978, a year after Elvis’s death, when I was an associate editor at the now-defunct music industry trade publication Record World, and a regular contributor to Rolling Stone, I received a call from a fellow I had befriended some years earlier, a true music business character of the type long since extinct in the industry, a boisterous Texan named Bill Smith, who prefixed his name with his Air Force rank of Major. He laid claim to having legitimately discovered Delbert McClinton and employing his harmonica artistry as a sideman on his hit production of Bruce Channel’s sole hit, 1962’s chart topping “Hey Baby”; later he launched McClinton’s recording career on Smith’s own LeCam label, as one half of the duo Delbert & Glen. LeCam was also the home of the Maj’s last great release, the #2 1964 teen death hit “Last Kiss” by J. Frank Wilson and the Cavaliers. Frantic as usual, the ol’ Maj was on the other end of the line proclaiming his gift to me of a “cotton-pickin’ worldwide exclusive”: through diligent investigation of Elvis’s death notices he had determined that no insurance claims had ever been filed by Elvis’s estate. To his way of thinking, this was proof that Elvis had faked his own death in order to be able to live a quiet life of meditation and relaxation away from the maddening crowds. Smith had concocted an entire scenario of what had happened and turned it into a spoken word recording titled “The King Is Dead???,” which was supposed to be pronounced “The King Is Dead, Question Mark, Question Mark, Question Mark.” He also claimed to have penned a screenplay depicting the faked death and a disguised Elvis fishing undisturbed on the banks of the Mississippi, unrecognized save by a young boy who shows up to fish with him, but is not allowed to speak Elvis’s name. Two weeks later the National Enquirer picked up my account of the Maj’s theory as published in Record World and turned “Elvis is alive” into a national obsession/delusion that persists in some quarters to this day. The ol’ Maj left this mortal coil at age 72 in 1994, and apparently got way out there in his latter years, touting a fresh, audiotaped interview with a man he claimed was Elvis. So blame me. I try to tell myself that the ol’ Maj could easily have found another willing journalist to report his findings had I turned him away, but in reflecting on the journalistic landscape at the time, it’s apparent that no one else was crazy enough to take it public, only me and the National Enquirer. You always want to travel in good company throughout life.

In truth the best part of the Elvis any of us will ever know is alive, and will be for generations hence, in the manner of Louis Armstrong, Sinatra, Jo Stafford, the Beatles and, for that matter, Michael Jackson.

We have the music. Make of it what you will.

***

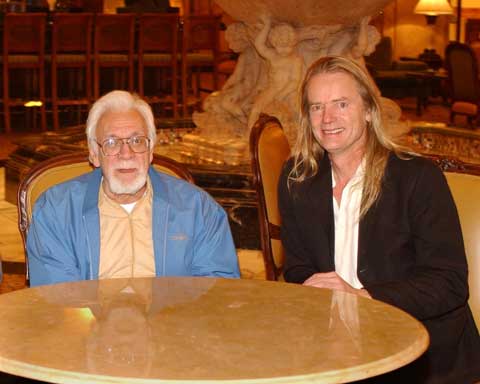

Recording engineer Bill Porter (left), an Elvis studio mainstay, with Ernst Jorgensen at the Peabody Hotel in Memphis. (Photo: Kevan Budd)A Conversation with Ernst Jorgensen

‘You can’t understand and appreciate the extent of Elvis' talent without going beyond the hits’

On the website for The Charlie Rose Show, Ernst Jorgenson’s bio is succinct: “Producer and catalog expert Ernst Jorgensen has been instrumental in the revival of Elvis Presley's body of recordings for nearly a decade; the box sets he co-produced for RCA, including The King of Rock 'n' Roll, From Nashville to Memphis, Walk a Mile in My Shoes and Platinum: A Life in Music, have been nominated for the Grammy Award and have sold well over a million copies. He is also author of the definitive account of Elvis' recording sessions, Elvis Presley: A Life in Music.”

There’s more to the man than that, of course, but it’s a fair summation of Jorgensen’s achievements as an Elvis chronicler. Better still is an autobiographical sketch he included in Elvis Presley: A Life in Music that traces the evolution of his passion for Elvis’s art. It reads in part:

But this is an oversimplification of a career devoted almost solely to setting the record straight on what Elvis the artist did, when he did it and with whom. Elvis fans should thank him –-and Peter Guralnick, and Elaine Dundy—for their diligence, for their insistence on separating myth from reality, and for their even-handed appraisals of the artistry. For Jorgensen, it’s been a lifelong quest, this Elvis fixation, and he explains its origins best in his own words, from the introduction to Elvis Presley: A Life In Music—The Complete Recording Sessions. Citing a statement Elvis made in August 1956, “I always felt that someday, somehow, something would happen to change everything for me, and I’d daydream about how it would be.” Jorgensen begins:

“I remember those dreams—not Elvis’s, but my own. The intense longing for something to happen, for my life to be somehow different from all of its predictable elements, its guarantee of what appeared to be a safe, boring future as a child growing up in Denmark.

“Riding to the post office on my bicycle through the snow at five-thirty in the morning, I had plenty of time to dream. As a teenager I had to support myself and my studies at the University of Copenhagen by working as a mailman in the mornings, but it sure wasn’t my likely future as a teacher that occupied my mind on those cold mornings delivering the mail. What I dreamed was that somehow I would get involved with Elvis Presley’s music; that I would come to understand how, when, and why it was made; and the someday, finally, I might come to understand why it seemed to have a greater effect on the world than any other music I knew.

“I wasn’t old enough to remember Elvis Presley at the start, when he was the controversial new American singing sensation of the ‘50s. You couldn’t even buy his records in Denmark until late 1958, and it wasn’t until 1963, at the age of thirteen, that I even got a record player. Like so many other Europeans, I was primarily exposed to Elvis’s early ‘60s material, songs like ‘It’s Now or Never,’ ‘Are You Lonesome Tonight?,’ ‘Can’t Help Falling In Love,’ and the one that really caught my attention—‘Little Sister.’ To most teenagers, music was very much a question of taking a stance. In my country you were presented with one simple choice—between Elvis Presley and England’s Cliff Richard—and if your position didn’t define who you were, at least it gave an indication of what kind of person you wanted to be. But all that changed very quickly—soon the choice was the Beatles versus the Rolling Stone—and over the next few years Elvis faded from the scene, leaving only the most diehard fans to admit that they still bought Elvis Presley records.

“I wasn’t one of those diehards. I bought Stones and Dylan albums, and later, records by the Doors and Jefferson Airplane. But I also started to collect the early Presley records—a treasury of wonderful, unknown music. Soon I’d become fascinated not just with rock ‘n’ roll but with the music that rock ‘n’ roll came from, opening up new doors to country, R&B, and gospel. I had no problem playing Jimi Hendrix back to back with any of Mahalia Jackson’s albums.

“My other main interests during those years were an insatiable appetite for detective novels and a continuing interest in the history courses I took at school. Somehow all these interests came together in my; pursuit of Elvis Presley. I found it impossible simply to dismiss my earliest hero, but I was still faced with the historical contradictions, the mysteries, of his music—the way he could go from the utter ridiculousness of ‘Old MacDonald’ to the masterfulness of ‘Big Boss Man’ within just months. Eventually I found two new friends, Johnny Mikkelsen and Erik Rasmussen, who not only shared my passion for music but were as intrigued by Elvis Presley as I—and who, like myself, were endlessly curious about the absolute contradictions and erratic logic of his recorded work and the way it was released. Together we started to collect information about Elvis’s music—only to learn that Elvis’s record company and management was enforcing a ‘no comment’ policy. Recording dates, background information: Everything was off-limits to the public.

“My friends and I were not easily dissuaded. Soon I was writing letters to his record company, session musicians, union offices, engineers—practically anybody we thought might have some answers. Maybe one out of ten, at best, would write back, but piece by piece we were able to organize our collections of Presley’s recordings and answer many of the questions that we (and, no doubt, plenty of other Elvis fans) had. There were significant breakthroughs when we got hold of all of Steve Sholes’s early paperwork; when RCA president Rocco Laginestra asked Joan Deary to send us a complete list of Elvis’s master serial numbers; and when Elvis’s producer, Felton Jarvis, started to correspond with us. At no time were the three of us producer than when, in 1974, Felton submitted a complete list of the Stax sessions he had held with Elvis a few months earlier, confiding in three Danish researchers about ten new titles that wouldn’t be released for another twelve months.

“At a certain stage in such endeavors, you reach a level of notoriety, and doors begin to open a little more easily. For us, that time came only after we had published several small pamphlets’ worth of all the information we had accumulated. All of a sudden we began to get responses in the form of additions, corrections, and general encouragement from like-minded folk around the world.

“Still dreaming about another life, I finally quit the university for a career in the Danish recording industry, which eventually led me to a job as managing director for BMG’s soon-to-be-opened offices in Copenhagen. BMG had acquired RCA Records in 1986, just two years earlier; now I found myself working within the company that owned Presley’s recordings. Some people at the label already knew about me and my interest in Elvis; indeed, several of BMG’s administrative departments were using our latest Recording Sessions booklet as their guide to the vast Presley catalog. Two years earlier I had hooked up with RCA’s entrepreneurial, London-based marketing director Roger Semon, whom I assisted in putting together several Presley albums especially for Europe. When we found ourselves working for the same company, we began to express our mutual concerns about the way the Presley catalog was being handled, and to our surprise we found that the new German international management was extremely supportive and encouraging.

“The record business is as tumultuous as any other, and after a few years it looked as if both Roger Semon and I were about to leave the company, when another unexpected turn of events occurred. Out of the blue, RCA’s New York office asked if we would like to work for them exclusively in restoring the Elvis Presley catalog. Organizing the releases and checking the tapes, a process I’ve been laboring at for nine years, has given me the opportunity to listen to every tape in the RCA vault; I spent literally thousands of hours cataloging Elvis’s music, poring over the snippets of dialogue captured on tape between songs, listening for clues, studying whatever facts and data we could, all in an attempt to reconstruct every aspect of Elvis’s recording career. As a consequence I came into contact with many of the people who had worked with Elvis and his music—each new contact another opportunity for more inside information. It is a process we are continuing today, and there’s plenty of work left to do.” (Ernest Jorgensen, Denmark, 1997)

Via email, Jorgenson, who lives in Denmark, engaged in a chat about the making of Elvis 75: Good Rockin’ Tonight and offered some general thoughts about the artist as well.

I've always thought one of the demarcation points between the true and casual Elvis fans is an appreciation for what you refer to as "deep cuts" in his catalogue—those album, soundtrack or bonus tracks that weren't hits—indeed, may not even have been released as singles—but are remarkable performances nonetheless. In 1991 RCA released an entire album of such recordings, called The Lost Album, and the only so-so recording on it was "Blue River." The rest were all first-rate performances, some quite amazing, all enjoyable on some level. You've probed the "deep cuts" on this box set, too, mostly on Discs 3 and 4, and one of the historically overlooked Elvis soundtracks, Spinout, provides two outstanding tracks, "Adam and Evil," and, above all, his only Dylan cover, "Tomorrow Is a Long Time," which Dylan himself has spoken favorably of, as well he should. Do you find these "deep cuts" as essential and revealing a part of Elvis's legacy as I'm making them out to be?

Ernst Jorgensen: I don't think you can understand and appreciate the extent of Elvis' talent without going beyond the hits, and beyond his concert performances. At the core of this are possibly his gospel albums, with the exception of "Crying In The Chapel," not hits, but filled with a musicality that transcends the genre itself—not just in the singing, but certainly in the musical arrangement as most significantly displayed on the “How Great Thou Art” masterpiece. Likewise with both blues and country, only marginally represented in his hit singles. Much as there is reason to dismiss many of his movie songs, simplification doesn't work here either—there are many precious cuts hidden on otherwise mediocre albums.

Speaking of "Tomorrow Is a Long Time," listening to it again I'm struck by one thing Elvis did not leave much of behind, and that is more of those austere, rootsy, small combo performances that really showed off so many aspects of his artistry all at once. In "Tomorrow Is a Long Time" it's the nuance in his vocal, the emotional shadings, against a backwoods arrangement; think about the "in the round" segment of the Comeback Special, and how great his guitar playing is in that situation—it took until 1968 but he laid to rest all criticism of his ability as a guitarist with that performance. When I was writing Carl Perkins's biography, Carl commented more than once about Elvis's solid rhythm guitar playing being almost as strong as that of his brother Jay Perkins, whom all the Sun artists I've spoken with over the years—including Johnny Cash—considered the embodiment of the model rhythm player.

Jorgensen: I agree—you only have to go back and play "That's All Right" to hear exactly what Elvis' guitar playing meant for his little band. He couldn't play a solo, but his sense of timing is what his guitar playing is all about.

Given that you must have had to account for the big hits, first and foremost, I'd say you used your remaining time on the four CDs to good effect, especially to spotlight Elvis's fluency in a variety of styles, from gospel to pop ballads to straight-ahead rock 'n' roll to country to blues to R&B. I love it that this box includes items such as "It Hurts Me," "Judy," "Reconsider Baby," "I'm Leavin'," and one of the great cuts from his second RCA album, "Paralyzed." So what was the operative philosophy guiding your decisions as to what to include as you waded through his extensive catalogue?

Jorgensen: The main idea with the non-hit cuts is to show other sides of his talent. But it was more heartache than anything—I would have loved to have more space—easily two discs more—an additional four discs would have been no problem either. Come to think of it, I'd love to release all in one package. If I could then get permission to rewrite history, I would be doing fine if I could just have had Elvis not record 100 of the 711 masters he did.

Elvis, ‘I Need Somebody to Lean On,’ by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman for the Viva Las Vegas soundtrack. A beautiful, nuanced blues ballad performance.You were onto something by including "I Need Somebody To Lean On" from the Viva Las Vegas soundtrack. Doc Pomus, who with his partner Mort Shuman wrote that song and the movie title track, told me once that he considered "I Need Somebody To Lean On" one of his best blues ballads, something that would compare favorably to Percy Mayfield's work, and that Elvis had transformed an exceptional song in ways Doc never anticipated—he always said of Elvis's recordings, "He sang the song-plus." What's your take on Elvis's singing, and, from the vantagepoint of one who's heard pretty much all of it, his development as a singer over the years? Because I'm struck by how moving and tender is his treatment of "Unchained Melody," recorded live in April 1977, just a few months, obviously, before his death. It sounds to me like he was still challenging himself, at least when he got a number he hadn't performed thousands of times before.

Jorgensen: I remember being upset with Elvis in the ‘70s—like most music critics, I wanted him to continue recording up-tempo stuff. When I got in my 30s I realized that Elvis was just being true to himself, by selecting material that was in line with his own life—in the his best moments a better interpreter of song than ever before—however to some over shadowed by the consequence his health had on his voice. Songs like “For Ol’ Times Sake” and “Pieces of My Life” (not on this box) are chilling examples of Elvis sharing what could be his most inner and personal thoughts—or yet again, maybe just emphasize his incredibly ability to "live" his songs. You don't really need a pretty voice for these songs. You need feeling.

After so many years of exploring the Elvis catalogue, assembling box sets, writing books about him, does he still surprise you?

Jorgensen: No, I don't believe he surprises anymore. What really surprises me is the willingness of the world to keep the many misconceptions of his career and life alive.

Which Elvis songs mean the most to you personally? And why?

Jorgensen: It's impossible for me to pick a favorite—it's actually meaningless, in that the most impressive fact is that he could brilliantly more from one genre to another, seemingly effortlessly, sometimes within minutes at a concert, and likewise in a recording studio. In the middle of recording his second Christmas album, he suddenly launched into an eight-minute jam of Dylan's "Don't Think Twice.” He could record gospel and R&B on the same recording session—just minutes apart.

You recently wrote to me that Carl Perkins's remembrance of his first encounter with Elvis, as I related it in his biography, could not have happened when Carl said it did, because you had uncovered documentation that indicates Elvis was somewhere else on the date in 1954 when Carl said he saw Elvis perform in Bethel Springs, Tennessee. That aside, it sounds like you're still exploring and investigating Elvis's life and career. Is this a lifelong mission then?

Jorgensen: Lifelong!! I have promised my wife to be a very old man, so I'm not sure that this is a lifelong mission. I'm currently working on what will be one of my most challenging projects, hopefully satisfying as well. It's a book/CD project devoted exclusively to the pre-RCA career of Elvis. I hope that this will come out in 2009.

Again, I recognize you had only a limited amount of space, even over four CDs, to provide an overview of Elvis's 30-plus year recording career. Given that, though, I found it odd that two strands of his career are underrepresented: one is Christmas songs, which number only one, "Blue Christmas," in this box set. I would have voted for both "Santa Claus Is Back In Town," from the Leiber-Stoller team on the first Christmas album, and one of Elvis's greatest latter-era blues performances, "Merry Christmas, Baby." I could name a few others off both albums, but these in particular stand out for me (notice I don't mention any of the beautiful Christmas ballads he recorded, especially on the second Christmas album). More curious, though, is there being only two—albeit classic—gospel numbers, "Peace In the Valley" and "How Great Thou Art"—from the artist who is one of gospel's most important practitioners ever. Does this reflect a personal preference on your part for the other music, or were Yuletide and gospel recordings simply a victim of numbers and space?

Jorgensen: We have just recently done a complete gospel box (I Believe), but in general apart from maybe the 20 biggest hits of Elvis, Elvis' gospel music and his Christmas recordings are some of his best sold records ever. So since space was scarce, I limited myself on these genres. I believe that “How Great Thou Art” is one of Elvis' biggest artistic triumphs and His Hand In Mine has a special place in my heart—the first Elvis album I ever bought!

Can you imagine Elvis at 75?

Jorgensen: NO!

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024