Going South

By Elaine Dundy

Author, Elvis And Gladys

Here and now I feel sure that in the next millennium, excavations on the site of what was once Memphis, Tennessee, will uncover artifacts which lead archeologists to conclude there was once a God called Elvis who resided in the sacred temple "Graceland" where his followers gathered twice every year to worship: on the day of his birth, and on the day of his death.

But prior to '77, I didn't know Elvis was alive until he died—a statement that is always greeted with howls of disbelief. People's memories are short. They forget that before his death it was possible to get through a day without hearing his name. I knew of course there was such a being, was aware of the tumult he caused but it was easy never to see an Elvis movie, nor watch him on TV, or rave about his act in Vegas. All that changed when he died on August 16, 1977. Curious I listened to one of his gospel albums, He Touched Me, and was instantly struck by his musical genius. I reacted with the zeal of convert, buying cassette after cassette of his albums, playing and re-playing them. His voice began singing inside me as it has with people the world over and knew I was going to write about him. I read every book on him I could find. They raised more questions than they answered.

I found it odd, for instance, that although Gladys, his mother, was certainly the pivotal influence of his life, his maternal line had never been explored. I was convinced that only with this kind of historical approach, with its emphasis on the interweaving of families, generations and customs, would the true meaning of Elvis' life unfold. It was vital to know who Gladys was, who her siblings were, her parents and grandparents. What was she like growing up as a child, an adolescent and a young woman before she married Elvis' father? Then I could understand how perfectly Elvis and his mother's needs dovetailed. I would go to his birthplace to find all this out.

In April of '81 I arrived in Tupelo staying at the Ramada Inn. I had no plan. I knew no one in Tupelo. That was the way I wanted it. I wanted to come from what has been described as “Innocence and Distance.” Actually it was the old Western movie gimmick: A stranger comes to town. I am that stranger. Let me take you with me as we mutually discover how and why Elvis became Elvis'

Though I was sure I had come South without preconceptions, I found myself having to discard one after another. It began shortly after my arrival. I'd drifted off to sleep to be awakened by the laughter of children in the Ramada pool. I went outside and in the dusk saw the pool filled with little black kids. I was astonished. Certainly black families would not be welcomed here. Didn't Mississippi have one of the worst civil rights records in America? I thought of the violent events set off here that summer when blacks sought their right to vote. I queried the man at the desk who informed me casually that Tupelo is a big family reunion town and that black families from everywhere in the country who have their roots in Mississippi, choose the Ramada for their yearly gatherings. This was one prejudice years out of date. (Later that night in the dark, my city psyche thrilled to the unfamiliar sounds of crickets, whippoorwills, frogs and the hooting of owls. Still later the sounds filtering into my room were those of a combo playing in the Ramada nightclub. The music was so good it lulled me to sleep. This, at least was one of the beliefs I came in with that checked out: no music played or sung by Mississippians would ever be bad. )

That trip I stayed in Tupelo for five months. There must be something to meeting your luck halfway because I had arrived on a Friday and by Sunday I was listening to a sermon preached by Brother Frank Smith, Elvis' boyhood pastor at the First Assembly of God church. His sermon surprised me: impassioned yes, fire and brimstone: no. It was on the healing power of tears. Nor was it the humorless congregation I had envisioned. The young soloist paused mid-note to say "Y'all have to pray for me, I've lost my key."

Brother Smith's wife, Corene, and I became friends. She had been a neighbor of the Presleys' when Elvis was a child. We would meet in the evenings at the Waffle House where, over hundreds of cups of coffee far into the night, she would talk to me about what Elvis and East Tupelo were like when he was growing up. Through her I was able to interview people who had never allowed themselves to be interviewed before.

My second friend was Phyllis Harper, feature editor and columnist of the Tupelo Daily Journal whom I met while going through its newspaper's archives. She had been born and raised in Fawn Grove near Tupelo and, after a cosmopolitan life, had returned. She knew the town inside out. She saw what I couldn't: why I was running into a wall of silence with certain citizens. Experience had turned them suspicious, Phyllis explained, they may have believed there was an Elaine Dundy whose novels were in the Lee County Library. They just didn't believe it was me. "I'm going to do a piece about you," she said suddenly. Her article, headlined "Established Writer in Tupelo to Research Presley," succeeded in validating me. It opened many doors not only important ones that might have been shut had I tried to storm them cold but doors I had no way of knowing even existed.

Tupeloans, I found, are in love with words. They recalled past events with a resplendence of language that made me see images rising up behind them as they talked.

The impoverished childhood of Elvis' mother was brought vividly to life by Mertice Finley Collins. She had watched the Smith children, of whom Gladys was one, growing up hungry "tumbling over each other" into the Finley's farmhouse where they were "strictly relegated to the kitchen." Only there could they be fed scraps by Mertice and her mother because her father "could not bear the sight of the pitiful little things swarming around his dinner table; their hungry faces upset him so."

Alongside the grim reality of belonging to a family reduced to sharecropping. living in shacks, working in the fields and at odd jobs, was the portrait Gladys at sixteen, slim, dark and beautiful, performing a wild and memorable Charleston. "Elvis got it honest. Gladys had rhythm," said her friend Grace Reed, favorably comparing Gladys' performances to those of her famous son's.

Picture perfect was the description a sister of Gladys gave me of three year old Elvis—when his father went to prison for forging a check—running up and down their little shotgun house, each time stopping to pat a dejected Gladys' on her hand saying "There. there, my little baby." The paternal absence and his mother's low spirits had created an early role reversal in Elvis. He thought of himself as the man of the house and his mother as his child to protect, to take care of. Elvis was not only a devoted son but a good and providing parent. From the age of twenty he was the sole support of his family and always referred to his parents as his “babies.” Aged ten, Elvis would be seen behind the wheel of their truck every Sunday driving the Presleys off to church. Even then the family seemed comfortably aware that he would always, and in every way, be doing the driving.

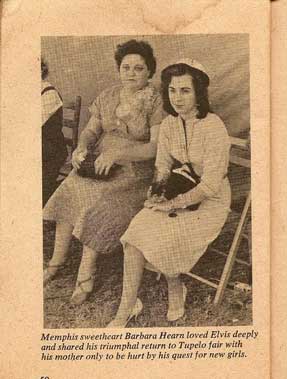

’Memphis sweetheart Barbara Hearn loved Elvis deeply and shared his triumphal return to Tupelo fair with his mother only to be hurt by his quest for new girls.’Who else but a Southerner could speak the following few words capable of resonating on so many levels: "Guess who I saw in town the other day? Gladys Smith, wearing a blood red dress and looking so pretty and so pleased! Told me she'd got herself married to one of those Presley boys from East Tupelo. You know, the ones from Above the Highway?" Thus Mertice's mother to her daughter at meeting Gladys soon after her marriage. In the swift sure portrait the speaker sketches first an exuberant Gladys proclaiming her rise in status by dress, manner, and marriage: then, with the phrase "Above the Highway" she effectively pin-points Gladys' downward economic status in a way anyone living in Lee County would have caught in a second. It was the derogatory term applied to a little five street community inhabited by some very poor whites in East Tupelo—itself the wrong side of the tracks.

Yet Elvis was formed by growing up in this community during the Depression. It was Corene who told me how it survived by everyone sharing what good fortune they had with each other. She owned the community camera; another shared her sewing machine; still others shared their radios. It was I believe, the root of Elvis' grown up generosity. Giving Cadillacs to strangers was his way of turning America into his neighborhood.

It was a front porch society where you stopped to pass the time of day with neighbors on their porches. It was also a singing society. In the evenings couples might get together on a porch and sing hymns or old favorites. The Presleys had fine voices an Aunt of Elvis said, adding, “Gladys sang alto." Had Elvis' formative years been spent in an urban setting, the Presley poverty would have been experienced as far more hopeless and humiliating.

After a month in Tupelo I started to feel the need of accurate dates, confirmed facts, all sorts of documentary evidence. I needed family trees with their appropriate backgrounds. I first met Roy Turner, a brilliant twenty-eight year old, in his house with his wife Debbie and their children. He was then the Corresponding Secretary of the Northeast Historical and Genealogical Society of Mississippi. His day job was working in public relations at Sunshine Mills. Over the breakfast table Roy and I sat from 4:00 p.m. till 10 p.m. while he pored over marriage, census, school, and cemetery records. He crash-coursed me in the arcane ways of genealogy, and the intuitive leaps you had to make before turning up a documented solution. It was better than a detective story. It was Roy who discovered that Elvis' great-great-great grandmother through her maternal line the Mansells was a Native American Cherokee named Mourning Dove.

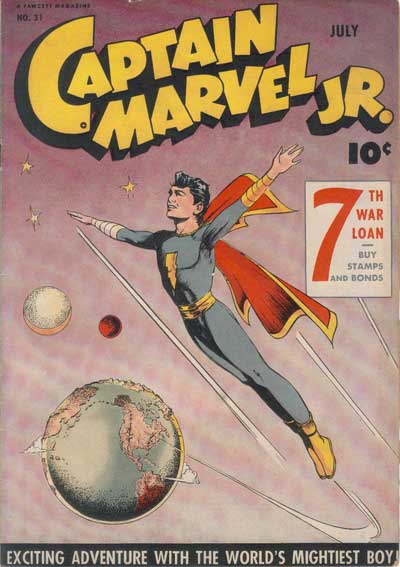

Back in London where I was living at the time I did some sleuthing on my own. Elvis was often quoted as saying that he was the hero of every comic book he'd read. One day I sat down in a comics bookshop to look at those popular when he was growing up. I looked at all those double identity heroes he must have read from Superman to the Spirit. Then I came across Elvis' face staring at me from its pages: It was the face of Captain Marvel Jr. Being himself a twin (who died at birth) the double identity of the powerful young Captain and the powerless Freddy Freeman existing in the same body would have a special meaning for Elvis: Here was the boy he aspired to be and the boy he was. I began to see how Captain Marvel Jr actually formed Elvis' personality—humble and humorous. How subconsciously the grown Elvis copied his hero's glistening black hair, his sideburns and his triumphant stance. Years later he wore his version of the Marvel Jr. cape. The white scarf Freddie Freeman often wore turned up around Elvis' neck in performance. Most important was Elvis taking over the lightning bolt emblem Marvel wore on his chest. It became Elvis' logo, his signature. The lightning bolt turned up on Elvis' private plane and in his game room. It turned up on the jewelry he gave special friends: the gold neck chains and bracelets. All of them were designed with Captain Marvel Jr.'s lightning bolt in the center.

Captain Marvel Jr. No. 31, July 1945: ‘It was Elvis twinning into Captain Marvel Jr. that made me see the powerful twinning force that ran through his life.’It was Elvis twinning into Captain Marvel Jr. that made me see the powerful twinning force that ran through his life. He twinned into all different forms of music, making him a different kind of singer from the great entertainers such as Al Jolson, Maurice Chevalier, Frank Sinatra, Bing Crosby, Judy Garland and Nat King Cole. They sang only in their own voices. Elvis had a whole range of voices he sang in which were appropriate to the song. As a tour de force country singer Buddy Bain pointed out that in the hymn "How Great Thou Art” you can hear Elvis go from Metropolitan Opera to country, to folk, to blues, to rock, almost from note to note without breaking his feel.

My book Elvis and Gladys took me four-and-a half-years and I wasn't bored for a minute. What I did not foresee was that I had embarked on journey that would continue to the present day. It had two lives. When first published in hardback it was well-reviewed and did fairly well. Only when it came out in its first large paperback edition did I begin getting mail from all parts of the world. By far the most frequent theme to emerge in these letters was Elvis as Healer, as Saver, indeed as Savior. It was uncanny how often these letters disclosed the same psychological profile and charted the same course. Brutal fathers and frightened mothers produced children who, by their own choice, "lived almost in seclusion." Then, discovering Elvis and his music, he became a major part of their lives. "Whenever anything went wrong," wrote a Canadian woman "I knew I could turn to Elvis' music and he would help me through." There was also, in late adolescence, a history of near suicidal attempts that the children saved themselves from because they "thought of Elvis" and even "heard his voice." His death has not ended his power in their lives and they still called on him in crises. One young boy wrote he was in a foster home in a small town in Michigan and asked me to tell him where the nearest Elvis Fan Club was. The letters reminded me of what a London psychiatrist had said. "When Elvis went into the army I had to treat English children for grief."

Elaine Dundy passed away May 1, 2008. This piece is reprinted from her website, www.elainedundy.com.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024