Let’s Go Surfin’

(Ed. Note: in 1978 Beach Boys scholarship was undeveloped almost to the point of being nonexistent. The band had been given its props by Rolling Stone in the ‘70s, but much of the band’s history was rumor and speculation, particularly relating to the dark side of Murry Wilson’s relationship with his sons and his stewardship of the band’s recordings in the early years. That year David Leaf, a staunch Beach Boys fan, published the first in-depth biography of the band, The Beach Boys And The California Myth, broadening and deepening the portrait Ken Barnes had offered in his 1976 book, The Beach Boys: A Biography In Words & Pictures, a work heavily reliant on secondary sources but also hinting at the larger story yet to be unearthed. Leaf did that, with what appeared to be extraordinary access to the Wilson family, and a knowledge of the inner workings of the business that led him to seek out important but theretofore unacknowledged cogs in the band’s breakout success, such as promoter Fred Vail. The weakness in Leaf’s story was in its being Brian Wilson-centric at the expense of the other musicians’ contributions and, indeed, growth. Nevetheless, Leaf’s book put the Beach Boys’ triumphs, follies, missteps and internecine squabbles on the record, but never at the expense of underestimating the music’s cultural impact on its time. It remains the definitive Beach Boys biography. In our continuing retro-summer celebration, we offer this from Leaf’s book, the chapter in which he chronicles the band’s rise from local favorite to bonafide national stars who had singlehandedly “brought the ‘California Sound’ and lifestyle attention on a national level,’ as Leaf writes. FYI: Leaf has gone on to an award winning career as a writer/producer/director with a wealth of memorable film and TV credits on his resume, a Grammy nomination for his Pet Sounds Sessions box set liner notes. His 2008 documentary, The Night James Brown Saved Boston, examining how the Soul Brother #1 calmed Beantown’s black community on the night Martin Luther King was assassinated, is one of the essential music documentaries. His daunting list of credits is available at http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0494938/.)

The Beach Boys’ first hit, “Surfin’,” made it into the top three in the L.A. radio charts, and peaked in Billboard magazine’s national charts at 75. The record sold somewhere between ten and fifty thousand copies, and the group received a check for less than a thousand dollars. Murry Wilson generously added a few dollars from his own pocket to make the total an even thousand, so that each Beach Boy got two hundred dollars.

One of the earliest Beach Boys concerts took place in the early spring of 1962. William F. Williams, one of the disc jockeys at KMEN in San Bernardino, recalls that time. “We at KMEN were one of the first stations to play the Beach Boys records, and San Bernardino was a big Beach Boys town. Harris department store had a ‘Deb-Teens’ department and the girls at the area high schools who bought their clothes there became members of a ‘club.’ Harris had a fashion show/concert each year for the girls who were members. KMEN was in charge of putting together the talent for Harris’s concerts, and I remember Murry Wilson came to us and literally begged us to let the Beach Boys be the opening act. As I recall, they barely knew which end of the guitar case was up. They looked very badly, played very badly, and sang very badly.”

Candix Records was having financial troubles, and it folded sometime before the summer of 1962. Russ Regan remembers that “Candix sold their masters to ERA Records. Because of that, Murry had the right to terminate. They had a clause in their contract that the Beach Boys couldn’t be sold to another record company.” Without a label, Brian was concerned over the future of the group. Audree remembers that Brian asked his father for help. “We’re really serious…We want to make records. Would you please help us?” Actually Murry had already assumed the reins. Although he never liked “Surfin’,” a record with no overdubs or hint of sophisticated recording techniques. “We did it all live. Our mix wasn’t as good [as today’s mix], it wasn’t as balanced. You couldn’t hear the guitar playing…you didn’t hear the bass notes as well…some of the vocals were a little buried. It wasn’t mixed and balanced very well. And my father was critical of the first thing we did; he said, ‘Well, look, you don’t hear the guitar, you don’t hear this, what is going on here? Listen, I’m going to have to take over as producer,’ which he did. He took over as a producer.” Offering help and encouragement, Murry horned in on the action. Without Murry’s presence, there might never have been even one record. With Murry, there was at least one adult who believed in the Beach

Boys.Hite Morgan was still the group’s publisher, so he and Murry began a search for a new recording deal. The group also went into Western Studios and cut a number of songs (probably “Surfer Girl,” “Judy,” “The Surfer Moon, “Surfin’ Safari” and “409), which Hite and Murry used to help sell the group.

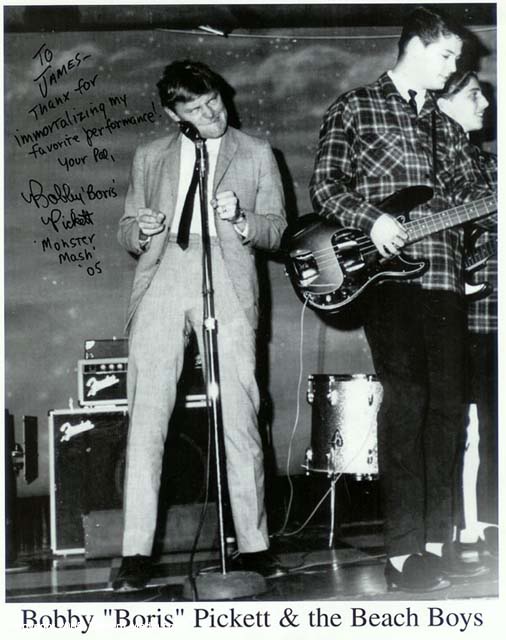

In the early days, the Beach Boys often backed other artists in addition to playing sets of their own. In this undated photo, Brian Wilson can be seen on bass at near right, with David Marks (who temporarily replaced Al Jardine in the lineup when Jardine returned to school) to his left, backing Bobby ‘Boris’ Pickett of ‘Monster Mash’ fame.Russ Regan, who had become Murry’s confidant in the record business, recalls that Murry didn’t want to sign with another company as small as Candix. “He wanted to be with a big company.” So Regan sent the demo of “Surfin’ Safari” to Wink Martindale, who was then an A&R man at Dot Records. According to Regan, Wink “heard the record, loved the record and played it for his boss. His boss turned it down because he felt that surfing music was just a flash in the pan.”

Mother Audree Wilson remembers that Murry and Hite “cooled their heels at Dot and Decca and Liberty.” Murry recalled in 1971 what had come next. “Finally, I asked Mr. Morgan what we should do. He says, ‘I don’t know. Murry, you’re their dad and manager, rots of ruck to you.’ And he says good-bye.” Nine years after the fact, Murry would still gloat: “That cost him two million, seven hundred thousand dollars, that statement. It cost him,” Murry repeated, “two million, seven hundred thousand dollars.” Murry, of course, was referring to the income that Morgan would have made as the publisher of Brian Wilson’s songs.

At the same time that the Beach Boys were searching for a record deal, they were undergoing their first line-up change. Al Jardine felt that the financial future of being a Beach Boy wasn’t all that promising, and he quit the group and returned to college with the intention of eventually going to dental school.

Taking Al’s place was a neighbor of the Wilsons’, fifteen-year-old David Marks, a youngster who fit well into the group. Audree Wilson, however, claims that “David played at guitar.” According to Audree, “Brian would not allow him to sing on record because he couldn’t sing… David was a pain in the neck, he really was. He would drive everyone crazy.” There were also reports that David’s mother, Joanne, was bent on making David a star, and that she and the Wilsons clashed frequently. Nick Venet, who supervised production on the Beach Boys’ early Capitol albums, recalls that Marks was musically competent as all the other Beach Boys (except Brian).

For the moment, nevertheless, Marks was a full-fledged Beach Boy. And when the group finally signed a contract with Capitol Records, it was David Marks, not Al Jardine, who was the fifth Beach Boy. By late ’63, Al Jardine had replaced Marks on a permanent basis, and David Marks was relegated to the land of trivia contests.

The Beach Boys’ first EP release after signing with Capitol Records in mid-’62: (from left) Brian Wilson, Mike Love, Dennis Wilson, Carl Wilson and short-lived Beach Boy David Marks.The signing of the Beach Boys to Capitol Records in mid-1962 was a key element of the success story. Without a major label, these five potential rock stars probably wouldn’t have made it. Brian might have had success as a composer, but it is unlikely that the others would have had musical careers. But that is all idle speculation because group did sign with Capitol.

Russ Regan: “I had written and done some demos with Nick Venet, so I told Murry, ‘Look, go over and see Nick Venet at Capitol because I think this is something Nick will really go for.’ The rest is history.”

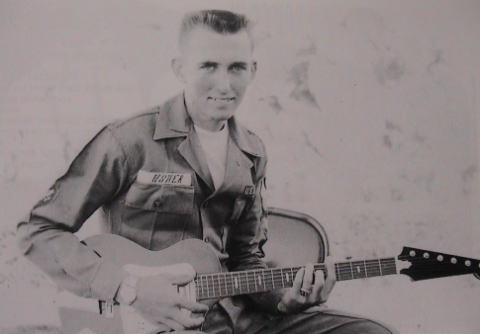

Nick Venet

Nick Venet was a twenty-one-year-old staff producer at Capitol Records in 1962 and was one of the few men in the record business who seemed to understand the importance of “teen” music. As a producer, he had already achieved some success at Capitol, but in those days, the record producer wasn’t very involved.. Sometimes, the producer’s most important role was just deciding which songs the artist should record.

It was into this world that Murry Wilson brought a demonstration record. That same day, he emerged from the Capitol Tower with a recording contract for the Beach Boys. Nick Venet was the man responsible for signing the Beach Boys to Capitol. Nick, however, is not a man that the Wilson family remembers fondly. Because Venet has been outspoken about his dealings with Murry Wilson and his role in the early Beach Boys’ records, he is disliked by the Wilsons.

Murry Wilson

The relationship got off to a shaky start. Murry had called for an appointment, and Nick asked Mr. Wilson to wait for two weeks because he was on his way to Nashville on business. Nick feels that Murry was insulted by the delay. They finally got together at the Capitol Tower and Murry played the demonstration record. As Venet remembered, “Every once in a while as a producer…before the second eight bars have spun around, you know that the record is a number-one record.” Venet was talking about “Surfin’ Safari.” He recalled that there was something special about it. “I wasn’t one for hiding my feelings. I mean, if I wanted to drive a bargain, I should have just sat there mum, but I got all excited, and I started jumpin’ around, and I said, ‘We have to make a deal.’”

Murry Wilson remembered it quite differently. “Nick acted real cool. He said, ‘You come back in an hour, and we’ll let you know if we want you to become Capitol artists.’ He didn’t act like he was too excited.”

This historical contradiction is the first in a series of disagreements that have occurred in print between Venet and the Wilson family. Audree Wilson thinks “the main problem was that he didn’t tell the truth.” Carl Wilson was more blunt. He said that Venet was “full of shit” when it comes to the Beach Boys.

Nick Venet dreaded Murry Wilson’s visits to the office. He had the receptionist warn him of Murry’s impending arrival and would hide under his desk.

Venet told writer Tom Nolan that Murry Wilson’s visits to his office were to be dreaded. He had the receptionist warn him of Murry’s impending arrival and he would hide under his desk. One day, Murry burst past Venet’s secretary, not believing her claim that Venet wasn’t in, and spent the entire day using Venet’s phone while Venet crouched under his desk. Audree Wilson counters that recollection by noting that Venet “really used to tell some copped-up stories. … Murry never used to go to Nick Venet after that first time, never. He had no reason to. …[Venet] said, for instance, that he’d see Murry coming and he’d hide under his desk. … Venet made Murry out to be some kind of monster. He liked, he really did.”

Murry was abrasive in his dealing with Capitol, but he was fighting for his sons. What Venet really objected to were Murry’s musical ideas. Venet noted that Murry felt that Brian could be the next Elvis Presley. Venet also recalled that Murry “wanted to elevate the boys by putting them into ‘pretty music.’” According to Venet, Murry Wilson’s music was from another time, the schmaltz of the early- and mid-twentieth century and Murry didn’t really know “where his sons were at. … I think Murry really fucked up the group for a couple of years.”

The feud reveals a lot about the worst side of both camps, and the intermittent battles made the early years of the group’s Capitol stay very unpleasant. But regardless of the bad feelings between Venet and the Wilsons that immediately developed, Venet did persuade Capitol vice president Voyle Gilmore to purchase the Beach Boys demo for three hundred dollars. The signing also included a five percent royalty, and although it wasn’t a generous deal, it was fairly typical for the times. For the Beach Boys, it was an exciting opportunity to make more records.

The Beach Boys, ‘Surfin’ Safari,’ the band’s first Capitol release, was a two-sided hit (with ‘409’ on the B side). ‘It was beginning to look like the Beach Boys might be around for awhile…’The group’s first Capitol release was “Surfin’ Safari” on one side and “409” on the other. The co-author of “409” was Gary Usher, the newest member of the Beach Boys family. Usher’s uncle, Benny Jones, lived near the Wilsons in Hawthorne. Uncle Benny suggested that Gary go over and meet the Wilsons as Gary also had a record out, and they would have something in common. Finally, one Sunday, as Usher recalls, “I went over and talked to them, they were practicing, you could hear them all over the neighborhood.

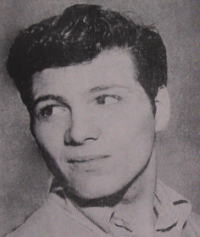

Brian says Gary Usher (above) ‘showed me how to write songs; showed me the spirit of competition.’ Of Brian, Usher says: ‘He knew all about the Four Freshmen, but he needed someone to help him break it down into contemporary forms and make that vast knowledge apply to rock and roll. In some respects, I was a channel for that.’“I seemed to hit it off with Brian right away. I seemed to have a soul affinity with him. We could touch each other on many levels, even though neither of us knew anything about it at the time or how to do it.” This meeting took place in January 1962 and Usher remembers that “the first day I went over there, we wrote regularly. I played a little rhythm guitar and a little bass, not much, and Brian played interesting piano. He knew all the progressive progressions. He knew all about the Four Freshmen, but he needed someone to help him break it down into contemporary forms and make that vast knowledge apply to rock and roll. In some respects, I was a channel for that. ….In the beginning stages, it was vital.” Gary Usher’s role in Brian’s development was important, but as Gary notes, “Sometimes after your usefulness has been used up, the creative spirit moves along. And that’s good. It should happen that way, if it’s honest.” Brian has stated that it was Gary Usher who “showed me how to write songs; showed me the spirit of competition.” The first song they wrote together was “Lonely Sea,” which only took about twenty minutes to write, as Gary recalls. Besides working together, Brian and Gary also became very close friends.

One of the early songs they wrote together was “409,” a paean to a hot rode that Usher hoped he might some day own. That song was part of the package sold to Capitol, and it was one side of Beach Boys’ first Capitol single, “Surfin’ Safari”/”409.” “Surfin’ Safari” was a big, overnight hit in cities like Phoenix, Arizona. “409” was also a hit, giving the group its first two-sided success. Most rock groups had a few hits and disappeared, but it was beginning to look like the Beach Boys might be around for awhile.

Between that second hit and the release of their first album, the Beach Boys garnered some valuable recording and performing experience, which would greatly influence the careers of a Southern California duo who were “between hits.”

Dean Torrence, of Jan and Dean, first heard the Beach Boys “on the radio, driving down the Pacific Coast Highway.” Dean remembers thinking, “’My God, that sounds like our stuff,” and being flattered that somebody though tit was good enough to copy.’ I don’t remember ever feeling threatened. I was kind of interested.”

Jan and Dean finally met the Beach Boys at a concert. In those days they were called hops, and the two groups were doing their first show together. “Since we weren’t a self-contained band, [the Beach Boys] were going to back us up. So we met a couple of hours early in a house trailer and practiced…they learned our four songs and they had their six or seven.”

The scene of the hop was near Hawthorne, the Beach Boys’ home turf, and although Jan and Dean were the headliners, Dean recalls that “the audience was very pro-Beach Boy.” After all, they were the “local town heroes.”

‘Local town heroes’: An early Beach Boys concert shotLive performances by rock groups were short in those days, and Dean noted that “it went by pretty quickly. After they did their songs, we did our songs. We didn’t talk very much. The total concert was maybe a thirty-minute job.” But the audience wanted an encore. The two groups hadn’t rehearsed anything else, so Jan and Dean decided to perform two Beach Boys songs, “Surfin’” and “Surfin’ Safari.”

Dean remembers, “They kind of looked at us as if to say, ‘You’d do our songs with us and let us stand up front?’ They thought they had to stand in the back; they were really amazed. We had a lot of fun doing it.”

Jan and Dean realized that the trend in surfing music was a bandwagon they wanted to jump on, and they decided to record a couple of surf tunes on their next album, which they titled Jan and Dean Take Linda Surfin’.

At that time, Brian Wilson was writing the only vocal songs about surfing, so Jan and Dean called the Beach Boys and said, “We had so much fun at that concert, why don’t you guys get together and we’ll put your two songs on the album, and you can come and help us [record it]. They were thrilled. It was the first time their songs had been on an album.” Jan and Dean were the first to recognize the potential of the surfing trend. When Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys ignited new fads, like hot-rod songs, Jan and Dean were there. Aided by Brian’s songwriting, they had a long run on the charts milking the fads that the Beach Boys popularized and quickly deserted. Besides the records, which were Jan Berry’s province, Jan and Dean were great performers. As native Californians, their tanned, sun-bleached looks epitomized California to the world. To some, the Beach Boys and Jan and Dean were one and the same. It was all California music and all full of fun.

‘The Beach Boys just represented California to the rest of the country’

The arrival of the Beach Boys presaged a new trend in popular music—the self-contained band: a group that wrote, produced and performed their own material. Nick Venet offers an interesting perspective on what effect they had on the record business. “It was a shot in the arm for the entire industry. It was a new form of teenage music. It had nothing to do with your girlfriend, breaking up or driving off a cliff. It was a pure California phenomenon. The Beach Boys just represented California to the rest of the country, some sort of fantasy that was out there that just got triggered by the Beach Boys records.” Taking care of the business angle, Nick notes that their sales were overwhelming. Without the sales, the California fantasy would have been stillborn in Brian Wilson’s head.

Part of Brian Wilson’s struggle as an artist was the resistance that he received from the record industry. Nick Venet was part of that resistance; still, he has come to understand what Brian was trying to do. Venet feels that Brian was five years ahead of the industry and that he has suffered for it. Brian and the Beach Boys were one of the first acts to break out of what Venet termed “the major label syndrome.” Up until that time, all groups recorded in the studio provided by the label, used the engineers and producers and musicians that the label told them to use. Brian (with help from Murry) forced Capitol to let the group record outside Capitol’s studios and to produce themselves: a first for the business. By forcing that policy change, Brian helped free California for young up-and-coming producers and musicians. Venet noted that until then, New York had been the center for recording. Brian used the young unknown musicians, and along with Phil Spector, made people like Glen Campbell and Leon Russell studio stars long before they were successful on their own.

Roger Christian

Roger Christian, a disc jockey and songwriter who co-authored a number of great tunes with both Brian and Jan Berry, felt that “the Beach Boys were not accorded the respect [by Capitol] because they were kids. And half the time, they’d come in, they wouldn’t be wearing shoes, because that’s the way it was. It was a hard thing to get the older people at Capitol to accept that the Beach Boys were keeping them alive at the record company. Everything the Beach Boys did at Capitol, they had to fight for.” Christian recalls the battle over over whether the Beach Boys were going to record and notes that part of the Capitol contract was that you had to record in their studio. Roger thinks that the Beach Boys wanted to get out of Capitol because the studios were too large for the kind of music the group was doing.

Chuck Britz

Chuck Britz, who engineered almost all of the Beach Boys’ hits a Western Studios, feels differently. He thinks it was that the group didn’t feel comfortable at Capitol, and that Western was isolated from the business and therefore “they felt more free to do what they wanted to do.” Britz notes that in any in-house studio, “it’s easy for people to walk in and out and destroy the process that gets you going. If you’re in a groove, there’s nothing worse than somebody coming in and asking a political or financial question.”

Venet admits that the record companies in those days didn’t care about the artists. “If you had a hit record and wanted to spend all your money, fine, because the law of averages was that you weren’t going to have one tomorrow.” The record industry at that time was filled with a lot “old men” who had no vision, no understanding that the music that was happening was going to revolutionize the business. “The first Tycoon of Teen,” Phil Spector, had already fought his battles and had ultimately established his own company so that he would have artistic freedom. Brian was the first artist to battle the executives successfully.

Brian and Phil were loved for what they were doing. Hal Blaine, considered the leading session drummer in the world, worked with both Spector and Brian Wilson and notes that “we, as the ‘older musicians,’ appreciated Brian ‘cause at the time, I did sessions with guys who were into big band stuff, no pop music. They used to say things like, ‘Now, I don’t want you to tune up because we gotta play rock and roll.’ That’s why so many [of those] people are not in the business today; they felt that rock and roll was so beneath them. Everyone said, ‘That’s garbage, that’s junk, it’s crap. Why should we be subjected to play that kind fourteen-year-old high school music?’ No one knew that music was taking over the world, that it was what the world needed.”

The musicians dug Brian, but Capitol Records really never tried to understand him; they never cared about him as a person. Capitol’s disregard for Brian as an artist would severely damage Brian and the group’s career when they started to grow musically away from the surfer image. As Dean Torrence recalls, “The whole idea with the record companies is to use you up as fast as they can, and once they do, they move on.”

The move away from Capitol was an important step in Brian’s development as a producer. Roger Christian notes that Nick Venet had a definite idea of what a record would sound like, and Brian had his idea. Brian could take it from start to finish. He’d create the idea, produce it, and perform on it. Brian can handle it all. He knew what he could get out of his brothers, and how to work with them because they’d been doing it at home for years, and they didn’t really feel they needed Nick. So those early records Brian produced, and Nick executive produced.

Murry recalled that Brian came home one day and was almost crying and asked his dad for help: “Will you go down and tell Capitol we don’t want [Venet] anymore, he’s changing our sound.” Murry then told Capitol’s Voyle Gilmour, “You folks don’t know how to produce a rock and roll hit in your studios downstairs. Leave us alone,” Murry demanded, “and we’ll make hits for you.” Murry and the group won two major battles. They were given the right to record outside of Capitol, and they quickly pushed Nick Venet totally out of the picture.

The first two Beach Boys albums bear the credit, “Produced by Nick Venet.” Audree Wilson remembers that “Venet had his name on as producer, which is totally inaccurate. He had nothing to do with producing.” Venet explains that he did function as the Beach Boys’ producer. “I would help Brian choose which songs to record from the dozens he had written. Also, I was an objective viewpoint. I would say to Brian, ‘I don’t think you need to do the record over.’ The difficulty was, everybody was trying to write and arrange with him. His ideas were always better than anyone’s.”

Whatever Venet’s contribution, there can be no doubt that Brian was responsible for the development of the Beach Boys sound. Nobody, except Murry Wilson, would dispute that: “See, the whole world trade has given Brian credit for everything. Truthfully—I’m not beating myself on the back, but knowing them as their father, I knew their voices, right? And I’m musical, my wife is, we knew how to sing on key and when they were flat or sharp, and how they would sound good in a song.” Murry’s claim that he put on the echo and surged on the power “to make them sound like gods” isn’t exactly accurate.

As engineer Chuck Britz remembers it, “That was his favorite line. Surge. He always said that. Surge here, surge there. I wouldn’t do it because you can only surge so much.” What Brian would do was to raise the volume of the control room monitor so that Murry would think that Brian was doing what Murry told him to do. On the actual recording, though, Britz wouldn’t “surge.” Britz notes that “basically, his ideas were right, like the dynamic power he wanted in a record, but you can only do so much. He was great; I really like Murry.” When it came to musical decisions, Britz recalls, it was almost always Brian. “Brian is the Beach Boys as far as I’m concerned. Brian was the only guy who could put all the parts together. The other guys helped a little, you’d see names, co-writer [etc.], but you’re talking about a guy getting credit that maybe just came up with a couple of changes, linewise. The basic principle and the basic song were his. [A co-writer’s credit] doesn’t mean you actually have much to do with the song. There’s a lot of people who give credit to other people. I still think the heaviest burden of it all was on Brian’s shoulders, and he knew it.”

‘Ten Little Indians’ was considered the Beach Boys’ first flop single. In the fall of ’62 it peaked at #49 on the national chart, but disappeared in eight weeks, in contrast to ‘Surfin’ Safari’’s 17-week chart run.Britz engineered every Beach Boys hit from “Surfer Girl” to ”Good Vibrations,” but wasn’t involved in the recording of the Beach Boys first flop single, a rather lame “Ten Little Indians,” the children’s chant given the Beach Boys vocal treatment. Even though it wasn’t a hit, the Beach Boys had a strong enough following by the fall of ’62 that the record made it into the top 30 in the Billboard charts, peaking at number 49. But it only remained in the chart eight weeks, as compared to seventeen weeks for “Surfin’ Safari.”

The Beach Boys’ success as recording artists, momentarily slowed by the relative failure of “Ten Little Indians,” picked up with the release of their first album, Surfin’ Safari. Its success firmly established the Beach Boys as the nation’s number one surfing group, and, combined with the hit single, made them a lot of money.

For Brian, that “overnight success, overnight wealth, hit me the hardest.” Brian welcomed his new lifestyle: “Just think, I don’t have to get up and go to work and make my money. The money’s rolling in from sales of records. I was just really set. It gave me a lot of confidence.” But sudden fame “was frightening to me..there were a lot of challenges to overcome. I just felt it was a challenge at first, to handle it, to handle the success that had come.”

The chief focus for Brian in those days was making hit records, as Brian once noted. “I don’t need money. I could care less about money as far as having to spend it. I really could care less about how rich I get.” As Audree Wilson recalls, “Brian was interested in the music if it was a hit, great, but he did not think about money.”

Mike Love, who will emerge as a “villain” in the fight between Brian’s art and commercial demands, recalled that it was “just unbelievable, the swift rise to a relatively secure position in music. People ask, ‘Wasn’t it a struggle? How long did it take before you were recognized?’ And I say, ‘About two weeks.’” That hyperbole and inaccurate boast aside, Mike continued: “The first song we did became a hit. The second song we did was a bigger hit.”

While the Beach Boys’ recording career was beginning to earn them considerable money, the Beach Boys as a live act was not a particularly impressive money making machine in 1962.

By Murry’s own admission, he held them back from major concerts because he didn’t think they were ready for the “big time.” He booked them at record store openings and local dances. Audree remembers that they used to drive to San Bernardino and other cities to play free shows. “It was a smart move, actually,” Audree feels. “The DJ’s were all putting on their own dances at that time. They’d call, and we’d go.” What no one will admit on the record is that although the guys were never paid for what Murry called the “forty freebies,” the Beach Boys did receive compensation in the form of valuable airplay. Because payola or plugola is illegal, nobody will acknowledge being involved, although it appears to have been a standard practice in the small towns for DJs to play the records of the groiups who played “for free” at their dances. On the surface, it’s not a very sinister practice and it was a very good way for a group to build a following. Today, payola has been refined and is now practiced as a very subtle and sophisticated art. Rock writers and DJs receive free records and concert tickets and press junets (and drugs?), and there is the implied promise of advertising for your magazine or radio station if you give explosure to one of the company’s artists. Airplay is strictly controlled today, and it is hard to purchase it overtly.

Besides the free shows, the steadily improving Beach Boys did play many gigs for pay, both as a featured attraction and as a backup band. Roger Christian remembers that he “used t do record hops, and the Beach Boys or the Surfaris were my backup group. I used to pay them about a hundred dollars a night, twenty dollars a man.” Bob Eubanks, best known for hosting TV’s The Newlywed Game, was a Los Angeles DJ in 1962. He recalls: “When I was a DJ at KRLA, I would hire the Beach Boys. I would pay them a hundred and fifty dollars to come out on Friday night and play Rainbow Gardens.” Bob “had a good relationship with the guys, they were very nice. It was obvious that the father was the true boss of what was going on. I always thought Murry was a bit of a bullshitter, but he was in there plugging for his boys. For that, I admired him.” Eubanks also tried “to get them to change their name because I felt that their name was so regional that they wouldn’t have much success out of a coastal area.”

Their records were already making the Beach Boys a well-known inland group, but as performers, they hadn’t strayed too far from L.A. The Beach Boys were still basically a regional act as 1962 came to a close. Nineteen sixty-three would be the year they would become national stars,

1963: Making Their Mark

The third year of the Beach Boys’ existence, 1963, was the year they made their first mark on the burgeoning youth culture. In fact, the Beach Boys’ impact was an important first step toward creating a “Sixties youth” that was different from the “Happy Days” of the Fifties. The Beach Boys were singing about surfing and hot-rodding and surfer girls, but the song content was really more a metaphor for a sense of freedom. The group’s music didn’t have anything to do with adults, and that message came through quite clearly.

For teenagers in 1963, the Beach Boys were one of the first groups singing directly to them. The Beach Boys weren’t singing about dissent and drugs—that wasn’t what was happening at that time. The music functioned as a bridge between generations. It was the Beach Boys who blasted the Frankie Avalons into oblivion. After all, who needed those noxious teen idols (they could only carry a tune) when there was a group of good looking guys who not only could really sing, but were writing their own songs and playing their own instruments.

Jan & Dean, ‘Surf City,’ part of a two-pronged musical attack masterminded by Brian Wilson that first cemented the allure of California firmly in the hearts of America’s youth. Brian sings background on the track.Only a few of that group’s fans rushed out and bought surfboards. Many of them, however, did buy the image of the ocean, the sun, and all the guys and girls who “were either out surfin’ or they’ve got a party going.” That’s from “Surf City,” an irresistible idyllic fantasy that appealed to millions. Actually, it was only part of a two-pronged musical attack masterminded by Brian Wilson that first cemented the allure of California firmly in the hearts of America’s youth.

First, there was the Beach Boys’ own “Surfin’ U.S.A.” Brian took an old Chuck Berry hit, “Sweet Little Sixteen,” and transformed it into a surf anthem. Surfin’ Safari, the Beach Boys’ first album, had extolled the virtues of the surf life, but hadn’t quite made it on sociological (let alone musical) terms. This time out, Brian struck a truly responsive chord. His universal surfers hit home in even the most land-locked locales, and “Surfin’ U.S.A.” reached number 3. Brian had conquered the airwaves; next he would control the fantasies.

With superlative ease, Brian conceived “Surf City,” a place where there were “two girls for every boy.” In those blissfully chauvinistic days, what red-blooded male could willfully resist the picture of two tall, blond Amazonian girls hanging on his arms while he braved the waves? Curiously, it wasn’t the Beach Boys who got to sing about “Surf City.” Friends and cohorts Jan and Dean had the number one smash with the song, a sore point between Brian and the family, especially when they realized that Brian was singing on the record. It really didn’t matter to the kids who was singing. The one-two punch of “Surfin’ U.S.A.” and “Surf City” brought the “California Sound” and lifestyle attention on a national level.

‘Surfer Girl’: beautiful song, beautifully renderedWith this magnificent myth in their back pockets, the Beach Boys finally broke out of the Southern California club scene and began playing dates all over the country, and, almost as important, began to make considerable money. The group’s success on the road, however, wasn’t the result of careful planning between Capitol Records and the William Morris Agency. Those companies often signed talent without knowing what to do with it. That was the case with the Beach Boys. Their touring success was due to the foresight of a nineteen-year-old promoter named Fred Vail, who lived in the decidedly non-surfing city of Sacramento, California.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024