Billie Holiday performing at New York's Downbeat club, February 1947. (Photo: William P. Gottlieb, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)'Unfortunately the song's relevance seems to deepen in our world today'

Filmmaker Joel Katz On His Documentary, Strange Fruit

Joel Katz makes films and videos that expand upon micro-histories to examine broader themes of social history and race in America. His works include Corporation with a Movie Camera (1992), a video about how corporate representations have shaped Americans' ideas about the Third World, broadcast nationally on PBS's New Television series in 1994 and now in worldwide distribution; Dear Carry (1997), a video based on the life of a New York jewelry designer and amateur filmmaker named Carry Wagner (1895-1992) that is also a documentary essay about ancestry, identity, cameras and travel. It premiered in 1998 in the Museum of Modern Art's "New Documentary" series and has shown in festivals nationally and internationally; and Strange Fruit (2002, national PBS broadcast; theatrical release). Katz is currently developing White: A Study in Color, a documentary about what it means to be white in America. Katz's work has been awarded grants by the National Endowment for the Arts, the Independent Television Service, the New York State Council on the Arts, the Jerome Foundation, and numerous other agencies. He has served on the Board of Directors of Third World Newsreel since 1999, and was a Fulbright Senior Scholar in 2008. Katz is an associate professor in the media arts department of New Jersey City University and is a member of the board of directors of Third World Newsreel, a New York-based advocacy and distribution organization for filmmakers of color.

In April 2003 PBS's Independent Lens series spotlighted Joel Katz's documentary, Strange Fruit. In the following Q&A, excerpted from a longer interview with Katz at the Independent Lens website (http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/strangefruit/qanda.html), Katz discusses why he made Strange Fruit, how audiences reacted to the film and how a song can change the world.

Why did you make this film?

I made this film because I wanted to honor people like Billie Holiday and Abel Meeropol who were brave enough to speak out about injustice in their times, even when such protests were often met with opposition. Strange Fruit is a film about a song that protests a human atrocity. Unfortunately the song's relevance seems to deepen in our world today. If we expand the meaning of the term "strange fruit" to encompass all persons who die unjust deaths, it is my belief that there is much "strange fruit" being created in Iraq now [April 2003.] Some of us feel that this is an injustice which must be protested and resisted, much as Holiday and Meeropol responded to issues in their own times.

How does the story of "Strange Fruit" resonate with your background?

In 1968, when I was 10 years old, my father (a Jewish man from Brooklyn) began teaching at Howard University, where he continued as a professor in chemical engineering until his retirement in 1986. As a Jew starting work at the preeminent African American university during the height of the Black Power movement, he was in a unique and sometimes difficult position. Over the years there he went through a wide range of experiences and emotions about this. Black/Jewish relations was thus a frequent subject of discussion at the dinner table as I was growing up. Seven years ago I began to teach at a public university that has a highly diverse student body. Thus I sometimes feel that I am carrying on the spirit of my father's work.

What material was the most difficult to edit out of your film?

It was difficult having the restraint not to play each performance of the song in its entirety. At first it seemed somewhat like a sacrilege to cut off a version once it had started. As editing progressed, however, I realized this was necessary not only to keep the program to time, but also to keep the editorial flow moving. There were a few versions of "Strange Fruit" which I very much wanted to use, particularly Nina Simone's, but I realized that the film could support only a limited number of performances, and that it is impossible to play a song in a film without compelling visuals to accompany it.

Your film has been shown at numerous festivals. What kind of feedback have you gotten from audiences?

Most of the feedback has been extremely positive. What is interesting for me is how different types of audiences bring different needs to the film. I've shown [the film] in quite a few Jewish film festivals, and there, the questions are often about the Meeropols, the Rosenbergs, the Jewish Left, etc. I've also shown the film at a number of Black film festivals, or settings in which the audience was primarily Black. In these contexts the questions are more often about lynching, the anti-lynching movement, etc. A few times there have been audiences that have been substantially mixed, which to me is the most interesting and productive situation.

What do you hope to achieve with this film?

I hope this film will give people hope—hope that creating a work of art, even just a short song, can play a role in changing the world. I also hope this film will help inspire some its viewing audience to carry on their own protests of injustice, however seemingly small. If the twelve short lines of the song "Strange Fruit" can make as enormous an impact as they have on the world, there is no knowing how important each small act of resistance may become.

(excerpted from an interview with director Joel Katz at PBS's Independent Lens website)

Nina Simone's version of 'Strange Fruit'***

'Strange Fruit': The Story Of a Song

By Peter DanielsSouthern trees bear a strange fruit

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root

Black body swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolias sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!Here is the fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop."Strange Fruit" was released on record in 1939, and quickly became famous. It had a particular impact on the politically aware, among artists, musicians, actors and other performers, and on broader layers of students and intellectuals. David Margolick's book, Strange Fruit: The Biography of a Song (originally published as Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday, Café Society and an Early Cry for Civil Rights by Running Press; it is now available from Harper Perennial), quoting numerous prominent figures, demonstrates how the song articulated the growing awareness and anger that was to find expression in the rise of the mass civil rights movement of the 1950s and '60s.

Abel Meeropol

Nevertheless, few of the millions who have heard "Strange Fruit" are aware of its genesis and history. It was written in the mid-1930s by a New York City public school teacher, Abel Meeropol, who was at that time a member of the American Communist Party, and who later became better known as the adoptive father of the two sons of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, the Jewish couple who were executed in 1953 for the alleged crime of giving the secret of the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union.

This history is related in Margolick's book, as well as in the 2002 film, Strange Fruit. The focus of the book is largely on Billie Holiday and her relationship to "Strange Fruit." The film, directed by Joel Katz, gives greater emphasis to Meeropol's story, and also presents interviews dealing with the historic and contemporary significance of the song..

It is the role of Meeropol, the composer of this song, that explains why it was shown at the Jewish Film Festival, an annual event at Lincoln Center in New York. A prolific poet and songwriter, Meeropol was born in New York in 1903 into an immigrant family. Like many of his background and his generation, he was radicalized by the Russian Revolution, the danger of fascism, and the Great Depression.

For decades the story has circulated, given credence by Billie Holiday's autobiography Lady Sings the Blues (co-written by William Dufty), that the song was written specifically for Holiday, or even that she had a hand in writing it herself. Meeropol credited Holiday for her unique and influential version of the song, but he insisted on setting the record straight when Lady Sings the Blues appeared in the 1950s.

The poem was written in the 1930s, after Meeropol saw a gruesome photo of a Southern lynching, and long before he met Holiday. At the time he was teaching at De Witt Clinton High School in the Bronx. "Strange Fruit" was first printed as "Bitter Fruit" in the January 1937 issue of The New York Teacher, the publication of the Teachers Union, in which the Communist Party then played a dominant role.

Writing under the pen name of Lewis Allan, the names of his two children who were stillborn, Meeropol set the poem to music on his own. For the first two years after it was written, the song was performed in political circles, at meetings, benefits and house parties. In early 1939, however, Billie Holiday was performing in the newly opened nightclub Café Society in lower Manhattan. Meeropol got the song to Barney Josephson, the owner of the club, and asked if Holiday would sing it. By some accounts, Holiday was at first not particularly impressed by the lyrics and perhaps not fully aware of the meaning of the song. Her rendition, however, made an enormous impression. She began performing it nightly, and then recorded it in April of that year.

Getting the song on record was not easy. Columbia Records, Holiday's regular label, refused to touch it. It was Commodore Records, a small outfit run by Milton Gabler, which released the song. Gabler, who is interviewed in the film, died in 2001 at age 90.

"Strange Fruit" was played only rarely on the radio. This was a period in which the segregationist Southern Dixiecrats played a leading role in the Democratic Party as well as the Roosevelt administration. It would take a mass movement to finally dismantle the apartheid system that played a key role in setting the stage for lynchings. There were, by conservative estimates, at least 4,000 lynchings in the half century before 1940, the vast majority in the South, with most of the victims black. There was little outcry over these pogrom-like activities. Socialists and communists were in the forefront of the struggle against lynchings.

Anticommunist politicians generally agreed with the Southern racists that the fight for racial equality was basically a left-wing plot, and anticommunist crusades certainly did not begin with Senator Joseph McCarthy in the postwar period. In 1941, Meeropol was brought before the witch-hunting Rapp-Coudert committee, which had been set up by the New York State legislature to investigate alleged Communist influence in the public school system. He was asked if "Strange Fruit" had been commissioned by the CP, or whether he had been paid by the party to write it.

Despite this political atmosphere, and the virtual banning of the song from the radio, at one point it was number 16 on the pop charts.

During the postwar witch-hunt, the performance of "Strange Fruit" became even more difficult. Some clubs refused to allow Holiday to sing what had become her signature song. She insisted on contracts specifying her right to sing it, but even that did not resolve the issue. Margolick's book relates how at one club on West 52nd St. Holiday cried after her performance. "Did you see the bartender ringing the cash register all through?" she said. "He always does that when I sing."

Interest and awareness of "Strange Fruit" appears to have dropped off, oddly enough, in the decades of the biggest civil rights protests. In recent years there has been a revival of interest in the song, however, as the many more recent recordings attest.

David Margolick's Strange Fruit: The Biography Of a Song is available at www.amazon.com

***

Lynchings and 'Strange Fruit'

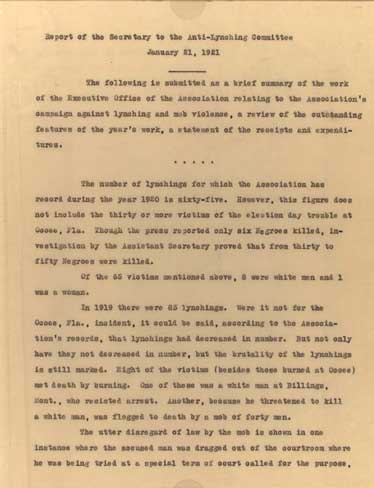

'The utter disregard of law by the mob is shown in one instance where the accused man was dragged out of the courtroom where he was being tried at a special term of court called for the purpose...'According to the Constitutional Rights Foundation (http://www.crf-usa.org/bria/bria10_3.html), between 1882 and 1968, mobs lynched 4,743 persons in the United States, over 70 percent of them African-Americans. Lynching peaked after the end of Reconstruction when federal troops were removed from the South. In 1892, vigilantes lynched 71 whites and 155 blacks. After that the number of lynchings decreased nationwide, but increasingly, lynching became a crime of the South. By the late 1920s, 95 percent of U.S. lynchings occurred in the South.

The white mobs who lynched African-American men often justified their actions as a defense of "white womanhood;" the usual reason given for lynching black men was that they had raped white women. But early on, journalists like Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) saw through this sham and proclaimed that the lynch mobs' real motive was the determination to keep African-American men economically depressed and politically disenfranchised. Ida B.Wells (a.k.a. Ida Wells-Barnett) headed the Anti-Lynching League and was a member of the Committee of Forty which led to the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

While the Constitution leaves law enforcement up to the states, a movement spearheaded by the NAACP sought to pass anti-lynching laws at the federal level, since Southern state governments appeared ineffective in fighting this crime. During the Great Depression, when Billie Holiday recorded "Strange Fruit," lynchings of African-Americans were again on the increase. Although a law at the federal level was consistently blocked by Southern senators, lynchings virtually disappeared by 1950. In part this can be attributed to improved economic conditions and the success of the anti-lynching campaign spearheaded by the NAACP.

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024