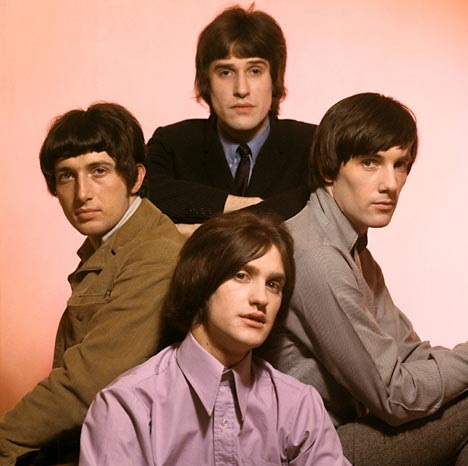

Pete Quaife (right) in the Kinks’ heyday, backstage with Ray Davies (left) and Dave Davies (center) (photo: Harrie Verstappen/the Loonispheres)‘Without Pete There Would Have Been No Kinks’

Pete Quaife

December 31, 1943-June 23, 2010Pete Alexander Greenlaw Quaife, the original bass player and, with Dave Davies, founding member of the Kinks, died of kidney failure in Herlev, Denmark, on June 23. He was 66. He had been undergoing kidney dialysis for the past ten years, and recently had put his talent as a graphic artist to use in publishing a book of cartoons titled The Lighter Side of Dialysis. He is survived by his partner, Elisabeth Bilbo, and a daughter, Camilla, from a previous marriage.

On his website, Kinks guitarist Dave Davies extolled Quaife as “a great musician,” adding: “You could always trust his playing, creative input, intuitive response to musical ideas. Without Pete there would have been no Kinks. The Kinks were never really the Kinks without him. I am overwhelmed with emotion—I literally can’t speak.”

Ray Davies’ website contains only a photo of the young Quaife, his birth and death dates, and RIP, but on the night he heard about his former bassist’s death, Davies dedicated a show to the fallen bassist.

After founding the Kinks with Ray Davies, then inviting Ray’s brother Dave to join them (Quaife was schoolmates with the Davies brothers), the band completed its lineup with drummer Mick Avory in 1963. In 1964 the Kinks broke out with a #1 British single, “You Really Got Me,” establishing itself on stage as both fashionably Mod and raucously hard driving. A string of hits followed in quick succession—“All Day and All of the Night,” “Tired of Waiting For You,” “Dedicated Follower of Fashion,” “Sunny Afternoon” and “Waterloo Sunset.” Quaife left the band in 1966 after breaking his leg in a car accident (he was replaced by John Dalton), but returned after he healed up, only to leave again for good in 1969, weary of the constant internecine warfare between the brothers Davies. He joined another band, Maple Oak, but quit after a year. He reunited with the original Kinks lineup for a concert in Canada in 1981, and rejoined them again in 1990 upon its induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Quiet and unassuming, Quaife toiled in the ever-lengthening shadow of Ray Davies, who developed into one of the most important songwriters of his generation with his lyrical, poignant portraits of the fading British empire and satirical jabs at pop culture trendiness; and Dave Davies, who came to be acknowledged as one of the finest guitar players to emerge from the British Invasion of the ‘60s, with a hard-edged but exceedingly tuneful style that had an impact on many of his peers, notably Pete Townshend. But Quaife was a fount of information about the Kinks, and on the rare occasions when he was sought out for interviews, always offered an interesting perspective on one of England’s greatest bands, from the vantagepoint of one who had a front-row seat to the proceedings. One of the finest of those interviews was conducted in June 1998 by Martin Kalin, for www.kindakinks.net. It is reprinted below; bear in mind this was 1998, so some of the references are dated (and the album Quaife says the Kinks were going to record has never surfaced), but it is vintage Pete Quaife nonetheless.

***

The Missing Kink

An interview with ex-bassist Peter Quaife

Martin Kalin interviews Pete Quaife at his home in Ontario, Canada, June 1998.It's 1998. Mention the Kinks to a casual music fan and he'll most likely respond with: "Are those guys still around?" This should be considered an acceptable reaction as the band hasn't released a CD of original material since the disastrous Phobia back in 1993. Compound this lack of contemporary originality with the fact that live Kinks concerts over the last decade have remained—for the most part—both sporadic and nostalgic.

Ardent audiophiles, on the other hand, will cite the ongoing, unplugged Ray Davies solo tour as one of the best live acts they've seen in years. This success obviously influenced Ray's younger brother/Kinks' lead guitarist, Dave Davies, who's formed a temporary back-up group for his own series of American and European club dates.

But long before the hiatus that the present line-up (Ray, Dave, Jim Rodford, Ian Gibbons and Bob Henrit) is undergoing, there was an earlier incarnation of the band that established themselves into today's modern rock legend. More importantly, most of the Kinks' best songs stem from the 1960's when the group included Ray, Dave, Mick Avory on drums, and Ray's boyhood friend, Peter Quaife, on bass guitar.

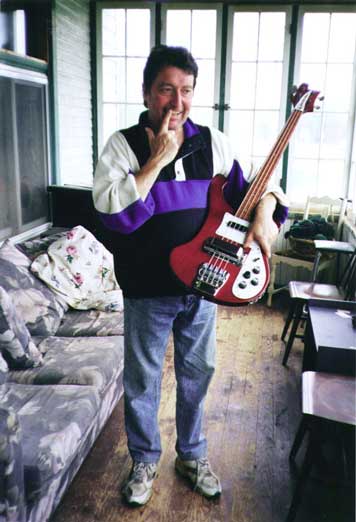

Pete Quaife with the Rickenbacker bass that is pictured on the cover of The Kink KontroversyAvory left the band in 1984, yet continued working behind the scenes at the Kinks-owned Konk Studios in London. Quaife's 1969 departure transpired with something more of a "cold turkey" divorce from his bandmates. Distancing himself—geographically and otherwise—Quaife moved from England to Denmark and then on to Canada, where he resides today outside Belleville, Ontario.

As a life-long Kinks' fan, I couldn't help but notice that Quaife's presence on most Kinks' websites was inexplicably sparse. Tracking him down through the magic of e-mail, Quaife invited me to his rural home for lunch and a casual discussion about life with and without the Kinks.

What question(s) do journalists and Kinks' fans ask you the most nearly 30 years since you left the band?

Do you know..? Have you ever been...? Is it true that..? Most of these questions are about rubbing shoulders with celebrity. I couldn't give a damn about all that nonsense.

It's 1998. How often—if at all—do you still talk to Ray, Dave or Mick?

All the time. The old saying "distance makes the heart grow fonder" is certainly true in our case.

What is the biggest lie you repeatedly hear or see written about the Kinks that has taken on almost mythological proportions?

That Dave did not play the guitar solo on “You Really Got Me” and that Ray and Dave formed the band. That's bollocks! It was Ray and I who formed the band. Those are the biggest tales. There are so many others that I couldn't begin to list them all.

You're famous for quitting the band, rejoining, then quitting again for good in 1969. There are various explanations as to why you quit. Do you wish to clarify what really happened...both times?

Well, the first time I was recuperating from a car accident so I couldn't have been there even if I wanted to. Inadvertently, it was a good break for me. The band was fighting all the time and I was getting sick of it. When I did quit altogether, I wanted to run as fast as I could in the other direction. I just couldn't take the constant brawling amongst everybody any more.

Did Ray encourage original material from you or—to a greater extent—Dave?

Are you kidding? I would have been squashed with a size 16 boot if I had have even suggested they listen to a new idea from me! Ray wanted complete control of everything. He was a control freak. As for Dave, well, I think Ray felt obligated to listen to his ideas a little more because he was blood. But Ray sure as hell didn't encourage it from Dave either.

The Kinks (clockwise from bottom center): Dave Davies, Pete Quaife, Ray Davies, Mick Avory: ‘The Kinks put on a happy facade to the outside world,’ Pete Quaife says. ‘Behind closed doors it was like the WWF (World Wrestling Federation). If we had have worked together in a more positive way, communicated. Talked instead of argued. I really think we hurt ourselves with the constant scrapping.’Not much is known about your vocal contributions to the band. Indeed a lot of the mixing on early Kinks songs blended the voices in an indiscernible manner. Which songs did you contribute vocals to in a significant way?

“Waterloo Sunset” was my most prominent contribution. As you say, most of the background singers that you can't identify include me.

Did you ever play guitar or any other instrument on any tracks?

No. I was a bass player and I was supposed to know my place.

Did you have a favorite album of the seven (six studio, one live) you did with the band?

Village Green Preservation Society. It was the one album where all four of us contributed ideas. It was the only project where everybody participated as a group. Ironically, it was my last album with the band.

Dave Davies was once quoted as saying the two best songs Ray ever wrote were “Shangri-La” and “Dead End Street.” In your opinion, what would be the top three songs Ray wrote?

“Waterloo Sunset,” “Animal Farm” and, I have to agree with Dave, “Dead End Street.”

A worst or least favorite song?

“Plastic Man.” I also don't like “Tin Soldier Man.” Bear in mind, I had to do concerts or T.V. appearances where I simply hated some of the numbers we were playing but I had to keep smiling.

Every armchair music critic has a theory as to why the Kinks never made it as big—in a mainstream sense of the word—as the Beatles, Stones or the Who. What is your theory?

I don't entirely blame external music industry forces. The Kinks put on a happy facade to the outside world. Behind closed doors it was like the WWF (World Wrestling Federation). If we had have worked together in a more positive way, communicated. Talked instead of argued. I really think we hurt ourselves with the constant scrapping. I remember, early on, that the Stones and us were about of equal popularity. I knew one of us would emerge as number two behind the Beatles. There was no way either us or the Stones were going to surpass the Beatles. The Kinks knew that. But we did have a chance to surpass the Stones if we worked as a collaborative unit and cut out the bullshit and fighting. I pulled Ray aside to talk about this and he told me to "sexually fornicate" off.

During your tenure with the band there were two different phases—musically speaking. The first period was your bluesy/hard rock period from 1964-66 with The Kinks, Kinda Kinks and The Kink Kontroversy. The second phase, where Ray "evolved" as a songwriter, covered Face To Face, Something Else and Village Green Preservation Society. Was there a different feel to things between these two phases and did you enjoy one over the other?

I would say the first period. I have a friend here in Belleville who's an old record collector. He asked me about my bass playing on our live album (Live at Kelvin Hall). He told me that it was some of the best bass playing he's ever heard. Plus that first period was before the fighting really, really escalated. But the fighting nonsense aside, let's face it: Ray Davies—pain in the ass that he could be—was a damn good songwriter.

It's probably fair to say that you and Mick Avory were less visible than Ray and Dave, simply because the media had the "Brothers Davies" angle they could use as a writer's device. As a result, did you and Mick bond in a different way?

Not really. But Mick and I felt like session men most of the time. Like it could have been anybody in the studio there playing bass and drums. That's not right if you're supposed to be a full-time member of a band.

Did you see Ray in Toronto when he brought his '20th Century Man/Storyteller Tour' there in October 1996?

No, I didn't. But I'll be meeting up with Ray and Dave in New York later this month and I hope to see it there. You know, at one of Ray's shows, I heard someone heckled something from the audience and Ray lost it completely. There was almost a fight from what I can understand. I'll have to get his side of the story on that one.

Have you read Ray's X-Ray or Dave's Kink literary versions of the band's formative years? If so, which is more 'accurate'?

I've read them both. Dave's is more factual and authentic. No question. Ray set his up as though he was interviewing himself. Well, if you do that you can rephrase your answer if you don't like it the first time. Dave revealed stuff that was going on at the time that I had absolutely no idea about. I said to myself as I was reading: "He did that?", "He said what?" Dave, the silly bugger, went as far as telling his wife in Los Angeles about his wife in London. Dave was the wild man out of the lot of us, that's for sure.

You've shown me your own literary work in progress. How will your book differ? When can we expect to see it available?

It's not about the Kinks. It's a fictitious piece of literature. A period story set in Muswell Hill. Because I live in Canada, I wanted a Canadian publisher so I could be close to the publishing process. I took it to Penguin Books but things didn't work out. I'm still talking to other publishers. It's been my main project the last three years. I've been doing mostly writing and my artwork has taken a backseat to the novel.

A lot of people don't know this but you did not quit the music business when you left the Kinks. Can you tell us a little about your post Kink career as a musician and why you eventually decided to leave the business once and for all?

Funnily enough, I met a bunch of Canadian musicians living in London at the time. We formed a band called Maple Oak. I was the only Brit in the group. It turned out that they were all really into drugs and that just wasn't my scene. The whole project was short-lived. After that, I moved to Denmark and returned to art as a profession and lifestyle.

Since leaving the band, did you continue to follow the Kinks' career throughout the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s? If so, do you have a favorite album that you weren't a part of?

I hardly followed them at all. I don't even know most of the songs or albums. I'm dreading it if Ray ever asks me to play these "latter Kinks" songs at a reunion gig because I haven't heard most of the stuff they did without me.

Were you surprised that Mick Avory stayed with the band until 1984?

I'm surprised Mick stayed alive until 1984! I truly thought he would quit before I did. But I still talk to Mick and he seems really happy today with his business role at Konk Studios. He also has a jazz band that he plays with.

In your opinion, what are the reasons why Dave never launched a full-time solo career?

It doesn't surprise me that he didn't. Dave was always insecure about his songwriting ability compared to Ray. He felt he would never be as good a musician as Ray was. That's funny, considering he was always a much better guitar player than Ray.

Did you ever strike up relationships with John Dalton or Jim Rodford?

Jim Rodford and Mick Avory are the two most down to earth guys you'll ever meet in your life. I met John Dalton, but we never established any kind of a relationship.

Have you ever attended a Kinks Konvention or seen the Kinks exhibit at the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland?

A Kinks Konvention, no. I was down in New York in 1990 when we were inducted into the Hall. That was before they built the museum in Cleveland. But I've been down to Cleveland a couple of times since. It's magnificent, as is the Kinks exhibit there. The four of us got to play together again at the 1990 induction. My wife has home video of Mick jokingly turning over furniture in our room at the Waldorf Hotel. The Kinks were famous for destroying hotel rooms when we got pissed off at each other. We were banned from so many places for that in our early days.

Let's play word or phrase association. What's your initial response to the following song titles:

“I Gotta Move”

It was okay.“Wicked Annabella”

Oh, great fun. I played a Bach bassline during the middle of that once.“Days”

Had a big fight over that one. Ray kept us in the studio so damn long I was beginning to lose my mind. My version of the "Daze" story is a little different from Ray's.“Set Me Free”

Hated it.“I'll Remember”

I don't.“Death of a Clown”

I liked that one. Good song.“Picture Book”

Ray stole the "scooby, dooby, doo" line from Frank Sinatra's “Strangers In The Night.”There seems to be debate as to whether you contributed any studio work to the Arthur album prior to your departure. Did you lay down any tracks for it?

I can listen to songs and detect my playing style. I know I did some work on some songs but I can't remember which ones.

What was the single most high point and what was your single, extreme low point with the band?

The morning after “You Really Got Me” hit number one, I woke up and lay in bed. I looked down at my feet and noticed a hole in the toe of my sock. At that moment I realized that I should be celebrating the moment with French chefs waiting on me and things like that. Not worrying about a hole in the toe of my sock. That was my high point. As for the low points, let's just say there were too damn many.

The Kinks, ‘You Really Got Me,’ the band’s first number one single: ‘The morning after ‘You Really Got Me’ hit number one, I woke up and lay in bed. I looked down at my feet and noticed a hole in the toe of my sock. At that moment I realized that I should be celebrating the moment with French chefs waiting on me and things like that. Not worrying about a hole in the toe of my sock. That was my high point.’Tell us about your career as an artist and what you're presently working on today?

My work is being showcased in a gallery down in Philadelphia called Imageworks. It specializes in artwork by musicians.

Tell us about your family.

I have a daughter from my first marriage. She's 30 and lives in Denmark. I've been married to Hanne, my second wife, for over 20 years.

Have you enjoyed relative anonymity since living in Canada or do fans recognize you in public?

When I lived in Denmark, people didn't care. All of a sudden when I moved to Canada, in 1980, it was a big deal again.

Did you take an oath of Canadian citizenship?

No, I'm officially a landed immigrant.

Did you choose to move to Canada or was it more of a career opportunity that presented itself here?

Hanne was from here. She was a Canadian living in Denmark when I met her. We moved to England for a while before settling here.

What do you miss about living in England?

The pubs. That's about it. I don't miss the weather. Canada's one place in the world where you're guaranteed a hot summer and a white Christmas.

Do you miss the music business and do you still write songs?

Yes. I don't even have to see a rock band. I was watching a classical orchestra on TV and I realized how much I still miss it. I play bass with a church group. My amp isn't even here, it's at the church.

Are all bass players really just frustrated guitarists?

Actually most are frustrated drummers.

You joined the Kinks on stage at Toronto's Maple Leaf Gardens in September 1981. How was that?

I don't remember. I was pissed drunk. It all happened by accident really. I was backstage and I was incredibly thirsty. I asked a roadie to get me a drink. He brought me what looked like a big glass of water with ice cubes. I took one gulp and the damn thing turned out to be vodka. I kept drinking it and by the time I joined them for an encore number I was out of it. Dave kept yelling at me, telling me I was playing in the wrong key.

The question that is on every diehard Kinks fan's mind—will you ever reunite with the original members to record anything in the future?

Yes. Ray, Dave, Mick and I are going into Konk Studios this fall. We're doing a CD of new material. Just the four of us. Just like old times. There'll be a fight. I can almost guarantee it.

Mick and Dave? Several books on the band say those two fought the most.

More than likely Ray and Dave. At first, when Ray approached me about this, I asked him if he thought it would be wise as he and Dave have stayed in shape, musically speaking, more than Mick and I. But Ray's behind the idea. I'm not interested in touring though. When you get older, a bass guitar becomes a lot heavier on your lower back.

Many fans say you "got out at the right time" or "the golden age of the Kinks ended when Peter Quaife left." How do you respond to this?

I agree. It's absolutely true, but I don't know exactly why. I don't have an answer or explanation as to the truth behind those statements. They called me "The Ambassador,” though. If you'll pardon the pun, I was the base of the group. I had a stabilizing influence on everyone. I often stepped in between a lot of the fights to calm things down. If we had have cooperated and worked things out, who knows? I might have stayed with the band and maybe things would have been different. I think the positive effect I contributed to the band was appreciated in more of a subconscious way. They probably didn't recognize my peacekeeping abilities until after I was gone.

I hate to ask this cliché of a question but...if you could do it all over again, would you change anything?

That we'd put all the altercations and abuse out the window. You know, we're the only band from that "British Invasion" era that hasn't suffered the death of an original member. I hope we regard that as a blessing when we all get back together to do our CD. I'd like to think that that's something special the Kinks still have.

Martin Kalin is a Toronto-based freelance arts writer. He is also the unofficial Kanadian Korrespondent for The Unofficial Kinks' Website. Martin can be reached at MKALIN50@hotmail.com. This interview was originally published at http://www.kindakinks.net/misc/quaife/.

The Kinks, ‘Waterloo Sunset’ live

THE BLUEGRASS SPECIAL

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024