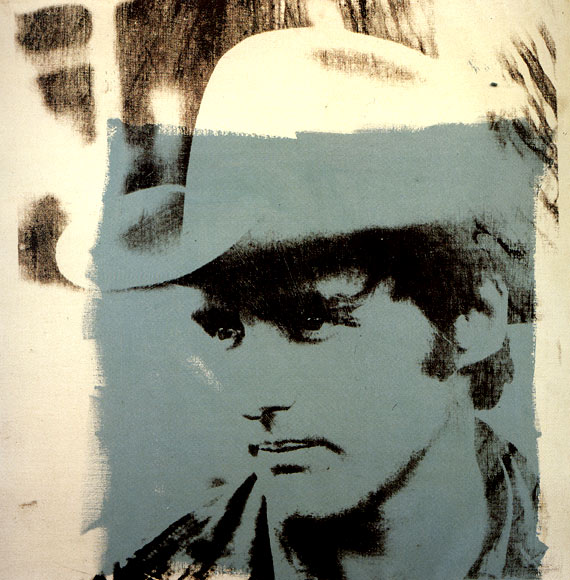

Dennis Hopper, by Andy Warhol, 1973: 'You know Dennis,’ laughed Nicholson. ‘You don’t exactly just turn over some money to him and say, ‘No problem,’ you know what I mean?’Dennis Hopper

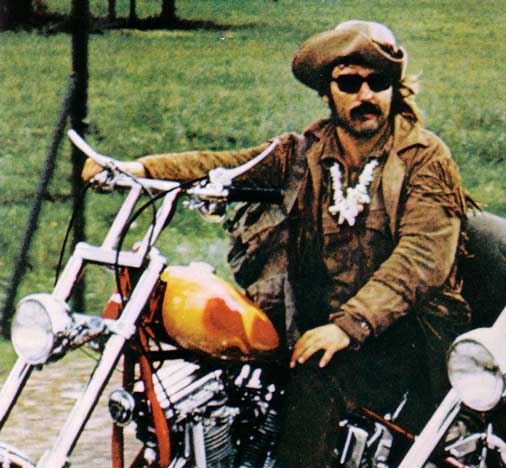

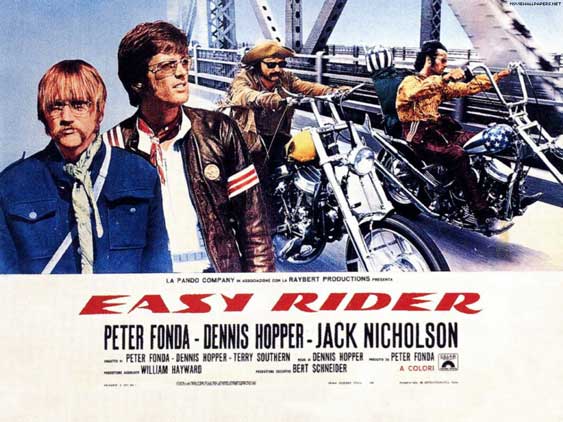

May 17, 1939-May 29, 2010Prostate cancer claimed Dennis Hopper’s life on May 29, but his is a career that will live on, both in the movies he made and in the legendary tales of excess and madness rampant in his biography. But for all that, Hopper was dedicated to his craft, a student of film and of acting, a distinguished alum of The Actor’s Studio who took his art seriously—maybe too seriously during those years he was in no condition to make sound judgments, but seriously nonetheless. There was more to be proud of than to disparage—from his rigorous portrayal of Jody Benedict, scion of the oil-rich Benedict family of Texas, who married a Mexican-American girl and refused to back down from the bigotry that greeted the couple’s union, as unflinchingly depicted in George Stevens’s 1956 big screen epic, Giant, which turned out to be his buddy James Dean’s final film; the autobiographical biker-doper-countercultural icon Billy in Easy Rider; the frenzied, paranoid photographer in Apocalypse Now; the alcoholic basketball legend attempting to reclaim his dignity and worth in an Academy Award nominated performance in Hoosiers (1986), and all manner of creepy and absolutely unforgettable sociopathic personalities he perfected on screen after sobering up (rarely more memorable, though, than his career reviving portrayal of Frank Booth in David Lynch’s Blue Velvet in 1986). In all, 55 years of film work, more than 150 films (half a dozen of which have been selected for preservation in the National Film Registry), a photographer-painter-sculptor of note, and as colorful a character as the 20th Century produced. We remember Hopper with a look back at one of his many defining moments, arguably the most pivotal of those defining moments, in Easy Rider, which he co-write with Fonda and Terry Southern, and directed.

‘Dennis Has Gone Berserk’

The long and winding—and crazed—road to Easy Rider, from inception to conception to execution, bruised feelings and failed relationships intact, with an over-the-edge Dennis Hopper at once in charge and non compos mentis. Excerpt Peter Biskin’s Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How The Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ‘n’ Roll Generation Saved HollywoodOne day, Hopper, Fonda and playwright Michael McClure dropped into the Raybert offices to pitch an idea. AIP was dragging its feet on Easy Rider, and nobody in his right mind would put up hard cash for bad-boy Hopper to direct. “You know Dennis,” laughed Nicholson. “You don’t exactly just turn over some money to him and say, ‘No problem,’ you know what I mean?”

Rafelson had met Hopper in New York, through Buck Henry. Bob had literally tripped over him on the floor at a party at Buck’s girlfriend’s apartment in the East Village. Hopper was pitching Rafelson McClure’s play The Queen, which featured the principals of the Lyndon Johnson administration—Johnson, McGeorge Bundy, Dean Rusk, and Robert McNamara—in white, off-the-shoulder beaded gowns, eating lobster and planning the assassination of JFK. Schneider limped in, his leg in a cast, and sat down at the desk in the back. Fonda and Hopper were about to go into Nicholson’s office to smoke a joint, but Rafelson introduced them to Schneider, saying of Hopper, “This guy is fucking crazy, but I totally believe in him, and I think he’ll make a brilliant film for us.” Schneider looked them over—Hopper, short and dark, in his filthy jeans, denim jacket, beard, ponytail, headband, his darting eyes shining with a paranoid glitter, a furrow slicing his brow like a knife. Fonda, tall and storklike, strikingly like his father, except for the long blond hair, fringed jacket, and rawhide moccasins—and listened to their rap. The Queen seemed a little much, even for Bert and Bob, and when Hopper asked for $60,000, Rafelson changed the subject, asked, “How’s your bike movie coming?” Fonda replied, “Oh, AIP is just dickin’ us around, man, puttin’ all these restrictions on us, it don’t look too good there.”

“Get the fuck outta my office and talk to Bert.” They did, and Bert agreed to finance The Loners, as it was then called, to the tune of $360,000. He did not have a studio lined up to distribute the movie, and he was using his own money to back Dennis and Peter, neither of whom had a track record directing or producing, but did have reputations as trouble. In other words, based an little more than a hunch, he was crawling very far out on an extremely thin limb. Moreover, he promised not to interfere. The idea behind Raybert, after all, was to enfranchise directors. Later, even when Bert disagreed with the casting of his movies, he backed down, saying, “What makes us right?”

With eleven points each (Terry Southern may or many not have had the other eleven), and Schneider the rest, Fonda and Hopper were ready to go. Bert wrote them a personal check for $40,000 so Hopper could film some scenes at Mardi Gras. It was sort of a test; if he passed, he could go ahead. But Fonda go the dates wrong. They thought they had a month to prepare; suddenly they realized they only had a week. Hopper scrambled to find friends who had 16mm cameras. They also realized they needed a proper producer, preferably somebody who knew his way around Hollywood. Paranoid as always, Hopper wanted to surround himself with relatives and friends. He called his brother-in-law Bill Hayward, and hired him for $150 a week. They quickly assembled a crew. There was a production meeting in Hayward’s office the night before they were set to leave. Everyone had long hair, was sitting on the floor. The meeting was very loose, very casual, very ‘60s. At one point, toward the end of the meeting, Hopper said, “All right, man, we don’t have a gaffer. Who wants to be the gaffer, man?” like he needed a blackboard monitor. Recalls Hayward, “Some broad says, ‘I’ll be the gaffer!’ She was a girl that had been sent out from New York to do still photography. Dennis said, ‘Fine. You want to do that? I can dig that. You’ll light the picture.’

“I knew then there would be trouble, because being a lighting gaffer is a real honest-to-God fucking job that requires some expertise,” continues Hayward. “Having a meeting for Dennis was like having an audience. There was no way he was going to listen to anybody else. It was all about his speeches. So when they get to New Orleans, there was war. Lots of people have never spoken to each other again, lots of hard feelings. And it was much worse than anybody thought it was going to be.”

Brooke Hayward drove Dennis to the airport. She said, “You’re making a big mistake, this is never going to work, Peter can’t act. I’ve known him since I was a child. You’re going to fail. I want a divorce.”

“You never wanted me to succeed, you should be encouraging me instead of telling me I’m going to fail. I want a divorce.”

“Fine.”

According to Hopper, “That was it. I never saw her again.”

He appeared to be in the grip of full-blown paranoia and, remembers Bryant, ‘he just started haranguing us about he he’d heard a lot about how many creative people there were on this crew, but there is only one creative person here, and that’s me. The rest of you are all just hired hands, slaves. He was totally out of his mind. He was just raving; probably had some combination of drugs and alcohol.’Margi Gras lasted five days. There was no script. Peter and Dennis knew the names of the two main characters, Billy, after Billy the Kid, played by Hopper, and Wyatt, after Wyatt Earp (aka Captain America), played by Fonda. They also knew they wanted to shoot an acid trip, but didn’t know much else. The three cameramen, Barry Feinstein, Baird Bryant, who had shot for New York underground filmmaker Adolfas Mekas, and Les Blank, later celebrated for his whimsical ethnographic documentaries, stumbled about in confusion. Hopper had told each one that he was the first camera. Recalls Peter Pilafian, Bryant’s soundman, “There was disagreement as to what the larger movie was, and what stage things would be at when the characters got to Mardi Gras. Dennis was this semipsychotic maniac. There would be a couple of handguns, loaded, on the table. He liked that kind of atmosphere.” Adds Bill Hayward, “He went right off the rails down there, just a completely fucking lost it.”

From Hopper’s point of view, there were too many chiefs, not enough braves. “Every one of them wanted to be a director,” Hopper recalls. “I didn’t want anybody shooting any film unless I told them to. But every time I turned around, they’d be shooting.”

The Byrds, ‘I Wasn’t Born To Follow,’ written by Carole King and Gerry Goffin, from The Notorious Byrd Brothers albumThe first morning, Friday, February 23, 1968, Hopper gathered the cast and crew in the parking lot of the airport Hilton at 6:30 in the morning. “I was really keyed up,” he says. “As far as I was concerned, I was the greatest fuckin’ film director that had ever been in America.” He appeared to be in the grip of full-blown paranoia and, remembers Bryant, “he just started haranguing us about he he’d heard a lot about how many creative people there were on this crew, but there is only one creative person here, and that’s me. The rest of you are all just hired hands, slaves. He was totally out of his mind. He was just raving; probably had some combination of drugs and alcohol.” According to Fonda, he raged at each astonished person in turn, “This is MY fucking movie! And nobody’s going to take MY fucking movie away from me!” until he shouted himself hoarse. Southern listened to Dennis’s performance, and made motions as if he were jacking off an enormous dick. He knew, as everybody did, that James Dean was Dennis’s guru. When Dennis came out with something particularly nutty, he’d say, “Jimmy wouldn’t appreciate that, Dennis.” Fonda was looking at his watch, thinking, “This is un-fucking-believable. We missed the start of the parade.” He continues, “Everybody was looking at me because I’m the producer, and all I could think of was, Oh, shit! I’m fucked. It’s my twenty-eighth birthday. What a fucking present I’ve given myself—this little fascist blowin’ us all off, absolutely going nuts.” Fonda asked Pilafian and the other soundmen to record surreptitiously Hopper’s ranting. He thought it might come in handy.

Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda, Toni Basil, Karen Black: The acid-drenched cemetery scene from Easy Rider. ‘Dennis and Peter had a serious falling out. Hopper was trying to get Fonda to bring up his feelings about his mother—who had committed suicide—for a scene in which he mumbles reproaches to a statue of the Madonna.’ Said Fonda: ‘I’m not takin’ Peter Fonda’s mother complex and puttin’ it up there on the screen.’People started quitting. On the final day, Hopper shot the acid trip in the graveyard with Fonda and actresses Karen Black and Toni Basil. “I showed up with my camera, and nobody else was there,” says Bryant. “The whole crew had just had it. Dennis bullied Toni to take her clothes off and crawl into one of those graves with the skeletons.” The cemetery sequence was the piece de resistance of the Mardi Gras shoot. It only took a day and a half, but Dennis and Peter had a serious falling out. Hopper was trying to get Fonda to bring up his feelings about his mother—who had committed suicide—for a scene in which he mumbles reproaches to a statue of the Madonna. “Here’s what I want you to do, man,” said Hopper, who by that time, late in the day, had had a generous helping of speed, wine, and weed. “I want you to get up there, man, I want you to sit on that, that’s the Italian statue of liberty, man. I want you to go up and sit on her lap, man. I want you to ask your mother why she copped out on you.”

“Hoppy, you can’t do that. You’re taking advantage. Just because you’re part of the family because of Brooke, that doesn’t give you the right to make me go public with it like that. Captain America don’t have no fuckin’ parents, man. He just sprang forth, just the way you see him. I’m not takin’ Peter Fonda’s mother complex and puttin’ it up there on the screen.”

“Nobody’s gonna know, man. You gotta do it, man.”

“Everybody’s gonna know, they all know what happened.”Although it was Fonda who was angry and upset, it was Hopper who was unaccountably close to tears. Fonda finally climbed up on the Madonna, and squeezed out, “You’re such a fool, mother, I hate you so much,” while Hopper watched, tears running down his cheeks. “That was the first time I’d ever vocalized any of that stuff,” says Fonda. “I actually started breaking down myself. I was sobbing.”

Reflects Hayward, “It may not sound like a big deal to most people, but it was an actor trusting a director and him going outside the bounds of what he was supposed to know. Peter never got over that. They developed a rift in their relationship that never recovered. I don’t know quite why it’s as bad as Peter—I mean, it kind of worked!”

Paranoid to the end, Hopper demanded Feinstein’s exposed stock, saying, “I don’t trust you—gimme all your film. I want it in my room!” Feinstein started throwing the film cans at him, whereupon Dennis jumped him, kicked and pummeled him. They went flying through a door into the room shared by Basil and Black. According to Dennis, Peter was in bed with both women. The two men paused for a second to contemplate this spectacle, and then Feinstein heaved a television set at Dennis. (Says Black: “I was never in bed with Peter Fonda, believe me.”)

As they were wrapping up in New Orleans, Peter called Brooke back in L.A. in the middle of the night. He said, she recalls, “We’re finished. Dennis is coming back tomorrow. I think you ought to take the children and get out of the house. Dennis has gone berserk.”

“Well, I’ve certainly seen—“

“No, this is much worse. And the footage is going to be dreadful, the whole thing is awful, it’s a disaster. I can’t work with him. I’m going to have to fire him.” She thought, I could take the children, but where am I going to go, and besides which, is that a good thing to do? Is it a nice thing to do? Is it the correct thing to do? A few hours later, she got a phone call from Southern that disturbed her more. He said, “You gotta get out of the house. We’ve all seen Dennis misbehave in the most terrible ways thousands of times in your living room, as you know better than anyone, but this time it’s really serious. This guy’s around the bend.” She was nervous, thought to herself. If Dennis knows he’s going to be fired, that’s going to make it trickier. He’s going to be under a lot of pressure. It could happen that he would strangle me to death, and not even know it. And then what would happen when the children found me in the morning? She decided to stand her ground.

When Hopper returned, he took to bed for three or four days, his custom when bad things happened, as they did all too frequently. “The dying swan,” as Brooke calls him, held court in the bedroom. Hopper finally got up to attend a screening of the Mardi Gras dailies for Schneider, Rafelson, and other interested parties. Recalls Bill Hayward: “It was jut an endless parade of shit.” Brooke, who went with Dennis, says, “It was just dreadful stuff, murky, the camerawork wasn’t any good. The talent I knew Dennis had, and Peter knew Dennis had, that we’d seen in the second unit stuff for The Trip that he’d shot, none of that was there. There was a terrible silence in that screening room.” Several days went by, with Peter presumably trying to find a replacement for Dennis, who was getting increasingly edgy. Remembers Brooke: “He was now drinking a great deal, and doing a lot of different drugs, which did not help his state of mind, and he was under the gun. He was violent and dangerous. Exceedingly dangerous.

Hopper claims he was unaware that Fonda wanted to replace him until Bert told him later that Peter had played the tapes of his tantrums in New Orleans for him and Nicholson. Bert said, he recalls, “I want to tell you about your friend Peter Fonda. He told me, ‘Hopper’s lost his mind, he’s obviously crazy.’ Peter and your brother-in-law Bill Hayward tried to get your fired. So you’re not confused about who your friends are.” Fonda handed Bert a check for $40,000, saying, “This is not going to work. When Hopper gets on the set, he loses it. I think he’s absolutely blown away that I’m the producer.”

“Well, don’t you want to make the movie?”

“Hell, yes.”

“Let’s find a way of doing it. I don’t think Dennis had the proper preparation, he doesn’t have the right crew, that’ll make a difference.”

One night, as Brooke prepared hot dogs and beans for the children, Dennis came striding into the house accompanied by underground filmmaker Bruce Conner, best known for a montage film called Cosmic Ray. Conner sat down at the Victorian organ, and started to play. According to Brooke, Dennis was incensed because the children had eaten all the food, leaving nothing for his dinner. She says that her little son Jeffrey stood in front of her with his arms crossed, saying, “Don’t you get near my mother.” With Conner still pounding at the organ like a mad Phantom of the Opera, refusing to look up, Marin began to scream, and Brooke thought, These children have already seen too much. If he gets any worse than he is right now, I won’t be able to handle it. I’ve got to get out of here. She took Conner aside, and pleaded, “Bruce, I want you to get Dennis out of here now, far away.” He replied, “I don’t want to get into the middle of this.” She hissed, “I’m not asking you to get in the middle of this. I want you to get him out of the house. On some excuse, go down to Malibu, go see Dean Stockwell, so I can get myself together.” Hopper and Conner left, Brooke packed up the children, and spent a week out in a shack where her friend Jill Schary lived in Santa Monica with her alcoholic husband. They slept on the floor in sleeping bags. “I went underground,” continues Brooke. “Dennis did not know where I was. I got a divorce lawyer, who said, ‘We’ve got to have a restraining order, but as long as he’s in the house—you gotta get him outta the house.’ Then my brother called me, said, ‘You’re not going to believe this, but Dennis has just been arrested for smoking dope on the Strip, and he’s in jail.’”

As Hopper recalled the incident, “They stopped me only because my hair was somewhat long, and I was driving an old car. They said I’d thrown a roach out of the car, which I had not. Well, I did have this roach in my pocket. Then, in court, they produce as evidence not my roach, which was wrapped in white paper, but somebody else’s roach, which was wrapped in black paper. How ludicrous, man! It was dark. They couldn’t have even seen a black roach.”

Continues Brooke, “I called my lawyer, said, ‘Dennis is in jail.’

‘Great. Go back to the house.’ That’s what did it. Dennis being in jail speeded up the restraining order. Bert bailed him out, and got Dennis out of town on a lengthy location scout. So that’s how I survived. It was just luck. If Dennis had been replaced, I’m sure he would have killed me.” Dennis and his close friend, production manager Paul Lewis, later broke into the house to get the art Dennis said was his, but they Brooke had removed it. She adds, “When we did get divorced, I probably could have gone for half of his cut from Easy Rider, but I refused to take a nickel from him, because I didn’t want him coming after me with a shotgun, and shooting me.”

Dramatis personae in the above excerpt:

You know Peter Fonda, Dennis Hopper and Jack Nicholson. Here’s some other key players in this excerpt:Bill Hayward: Dennis Hopper’s brother-in-law, by way of Hopper’s marriage to Brooke Hayward.

Brooke Hayward: Wife of Dennis Hopper, daughter of agent-producer Leland Hayward and actress Margaret Sullavan, former wife of Henry Fonda. When she and Hopper met, Hayward had two children from a previous marriage; after marrying Hopper in 1961, the couple had a girl, Marin, born in 1962. She told Peter Biskin, author of Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, that her marriage to Hopper began to fall apart after her husband attended the first love-in in San Francisco in 1966. He returned “into acid in a big way,” according to Biskin, who quotes Hayward as describing Hopper thusly: “He had a three-day growth of beard, he was filthy, his hair was crazy—he’d started growing a ponytail—he had one of those horrible mandalas around his neck, and his eyes were blood red. Dennis was altered forever.” (Painting of Brooke Hayward by Andy Warhol, 1973)

Raybert Productions: Production company founded in 1965 by Robert (Bob) Rafelson (at left in photo) and Bert Schneider (at right) that was successfully launched with its development of The Monkees’ group and TV series and became a force in the film world by co-producing Easy Rider with Pando Company. Even before Easy Rider’s success, director-writer-producer Rafelson had successfully collaborated with Jack Nicholson on the 1968 Monkees film, Head, and post-Easy Rider teamed with Nicholson on Five Easy Pieces (Rafelson directed) and four other films: The King of Marvin Gardens (1972), The Postman Always Rings Twice (1981), Man Trouble (1992) and Blood and Wine (1996). Schneider, son of former Columbia Pictures president Abraham Schneider, was expelled from Cornell University and bounced from the Army (the latter event owing to his radical activities) before he partnered with Rafelson and made it first on TV and then in movies. After taking on Steve Blauner as a partner and changing the company name, BBS Productions was behind Peter Bogdanovich’s classic The Last Picture Show (1971) and Rafelson’s The King of Marvin Gardens. Schneider himself earned a Best Documentary Oscar in 1975 for producing the searing documentary about the Vietnam War, Hearts and Minds.

Jill Schary: Friend of Brooke Hayward, and daughter of legendary movie director, writer, producer and playwright Isadore “Dore” Schary. His 1958 play Sunrise at Campobello (based on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s battle with polio) won four Tony Awards and introduced James Earl Jones to the Broadway stage. Writing under her married name Jill Robinson, Schary fils’ 1974 memoir, Bed/Time/Story, was widely acclaimed and won a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her widely praised fiction includes the novel Perdido. She currently blogs for The Huffington Post (http://www.huffingtonpost.com/jill-robinson) and her own website, www.jillscharyrobinson.com.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024