Hitchcock By Truffaut

The Making of PsychoIntentionally shot quickly in black and white and on a minimalist budget of $800,000 by a television crew, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho became, in the words of Hitchcock biographer Patrick McGilligan, “the most overly familiar picture in history,” spawning “innumerable essays, films, books, college courses, academic symposia, fan clubs, and Web sites devoted to extolling and analyzing the film.” This, from a movie Hitch pitched to Paramount as being, again in McGilligan’s words, “a simple, low-budget American shocker, in the style of his TV series, which would provide a breather from more lavish, grandiose productions.”

In the fall of 1962, French film director Francois Truffaut and author/translator Helen G. Scott of the French Film Office in New York engaged Hitchcock in 26 hours of interviews, which were edited into the 1965 coffee table book, Hitchcock by Truffaut: The Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock. A master of audience manipulation, Hitchcock perfected the art in Psycho. In this excerpt from the Psycho chapter of Truffaut’s book, Hitchcock explains the deliberate directorial choices he made, almost always with audience reaction in mind, in seeing Robert Bloch’s novel transformed into a “low-budget American shocker.” Says Hitch: “That game with the audience was fascinating. I was directing the viewers. You might say I was playing them, like an organ.”

Herewith, fascinating insights into the creative process that produced Pyscho, direct from the man responsible for this screen classic.

Francois Truffaut: Before talking about Psycho, I would like to ask whether you have any theory in respect to the opening scene of your pictures. Some of them start out with an act of violence, others simply indicate the locale.

Alfred Hitchcock: It all depends on what the purpose is.

The opening of The Birds is an attempt to suggest the normal, complacent, everyday life in San Francisco. Sometimes I simply use a title to indicate that we’re in Phoenix or in San Francisco. It’s too easy, I know, but it’s economical. I’m torn between the need for economy and the wish to present a locale, even when it’s a familiar one, with more subtlety. After all, it’s no problem at all to present Paris with the Eiffel Tower in the background, or London with Big Ben on the horizon.F.T.: In pictures that don’t open up with violence, you almost invariably apply the same rule of exposition: From the farthest to the nearest. You show the city, then a building in the city, a room in that building. That’s the way Psycho begins.

A.H.: In the opening of Psycho I wanted to say that we were in Phoenix, and we even spelled out the day and the time, but I only did that to lead up to a very important fact: that it was two-forty-three in the afternoon and this is the only time the poor girl has to go to bed with her lover. It suggests that she’s spent her whole lunch hour with him.

F.T.: It’s a nice touch because it establishes at once that this is an illicit love affair.

A.H.: It also allows the viewer to become a Peeping Tom.

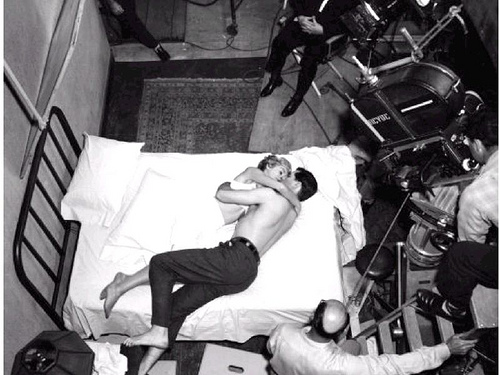

On the set of Psycho, filming the opening hotel scene with John Gavin and Janet Leigh. ‘In truth, Janet Leigh should not have been wearing a brassiere. I can see nothing immoral about that scene and I get no special kick out of it,’ Hitchcock says. ‘But the scene would have been more interesting if the girl’s bare breasts had been rubbing against the man’s chest.’F.T.: Jean Douchet, a French film critic, made a witty comment on that scene. He wrote that since John Gavin is stripped to his waist, but Janet Leigh wears a brassiere, the scene is only satisfying to one half of the audience.

A.H.: In truth, Janet Leigh should not have been wearing a brassiere. I can see nothing immoral about that scene and I get no special kick out of it. But the scene would have been more interesting if the girl’s bare breasts had been rubbing against the man’s chest.

F.T.: I noticed that throughout the whole picture you tried to throw out red herrings to the viewers, and it occurred to me that the reason for that erotic opening was to mislead them again. The sex angle was raised so that later on the audience would think that Anthony Perkins is merely a voyeur. If I’m not mistaken, out of your fifty works, this is the only film showing a woman in a brassiere.

A.H.: Well, one of the reasons for which I wanted to do the scene in that way was that the audiences are changing. It seems to me that the straightforward kissing scene would be looked down at by the younger viewers; they’d feel it was silly. I know that they themselves behave as John Gavin and Janet Leigh did. I think that nowadays you have to show them the way they themselves behave most of the time. Besides, I also wanted to give a visual impression of despair and solitude in that scene.

F.T.: yes, it occurred to me that Psycho was oriented toward a new generation of filmgoers. There were many things in that picture that you’d never done in your earlier films.

A.H.: Absolutely. In fact, that’s also true in a technical sense for The Birds.

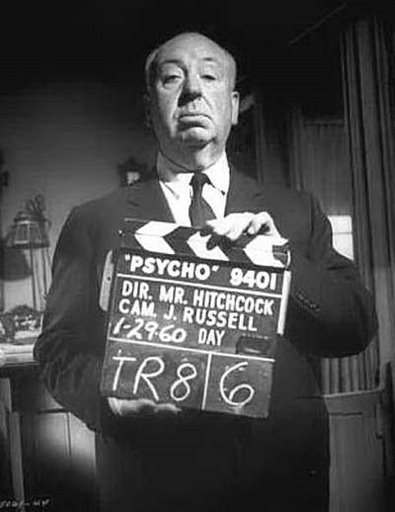

Alfred Hitchcock discusses Psycho in this 1965 interview first aired on French televisionF.T.: I’ve read the novel from which Psycho was taken, and one of the things that bothered me is that it cheats. For instance, there are passages like this: “Norman sat down beside his mother and they began a conversation.” Now, since she doesn’t exist, that’s obviously misleading, whereas the film narration is rigorously worked out to eliminate these discrepancies. What was it that attracted you to the novel?

A.H.: I think that the thing that appealed to me and made me decide to do the picture was the suddenness of the murder in the shower, coming, as it were, out of the blue. That was about all.

F.T.: The killing is pretty much like a rape. I believe the novel was based on a newspaper story.

A.H.: It was the story of a man who kept his mother’s body in his house, somewhere in Wisconsin.

F.T.: In Psycho there’s a whole arsenal of terror, which you generally avoid: the ghostly house…

A.H.: The mysterious atmosphere is, to some extent, quite accidental. For instance, the actual locale of the events is in northern California, where that type of house is very common. They’re either called “California Gothic,” or, when they’re particularly awful, they’re called “California gingerbread.” I did not set out to reconstruct an old-fashioned Universal horror-picture atmosphere. I simply wanted to be accurate, and there is no question but that both the house and the motel are authentic reproductions of the real thing. I chose that house and motel because I realized that if I had taken an ordinary low bungalow the effect wouldn’t have been the same. I felt that type of architecture would help the atmosphere of the yarn.

F.T.: I must that the architectural contrast between the vertical house and the horizontal motel is quite pleasing to the eye.

A.H.: Definitely, that’s our composition: a vertical block and a horizontal block.

F.T.: In that whole picture there isn’t a single character with whom a viewer might indentify.

A.H.: It wasn’t necessary. Even so, the audience was probably sorry for the poor girl at the time of her death. In fact, the first part of the story was a red herring. That was deliberate, you see, to detract the viewer’s attention in order to heighten the murder. We purposely made that beginning on the long side, with the bit about the theft and her escape, in order to get the audience absorbed with the question of whether she would or would not be caught. Even that business about the forty thousand dollars was milked to the very end so that the public might wonder what’s going to happen to the money.

You know that the public always likes to be one jump ahead of the story; they like to feel they know what’s coming next. So you deliberately play upon this fact to control their thoughts. The more we got into the details of the girl’s journey, the more the audience becomes absorbed in her flight. That’s why so much is made of the motorcycle cop and the change of cars. When Anthony Perkins tells the girl of his life in the motel, and they exchange views, you still play upon the girl’s problem. It seems as if she’s decided to go back to Phoenix and give the money back, and it’s possible that the public anticipates by thinking, “Ah, this young man is influencing her to change her mind.” You turn the viewer in one direction and then in another; you keep him as far as possible from what’s actually going to happen.

In the average production, Janet Leigh would have been given the other role. She would have played the sister who’s investigating. It’s rather unusual to kill the star in the first third of the film. I purposely killed the star so as to make the killing even more unexpected. As a matter of fact, that’s why I insisted that the audiences be kept out of the theaters once the picture had started, because the late-comers would have been waiting to see Janet Leigh after she disappeared from the screen action.

Psycho has a very interesting construction and that game with the audience was fascinating. I was directing the viewers. You might say I was playing them, like an organ.

F.T.: I admired the picture enormously, but I felt a letdown during the two scenes with the sheriff.

A.H.: The sheriff’s intervention comes under the heading of what we have discussed many times before: “Why don’t they go to the police?” I’ve always replied, “They don’t go to the police because it’s dull.” Here is a perfect example of what happens when they go to the police.

F.T.: Still, the action picks up again almost immediately after that. One intriguing aspect is the way the picture makes the viewer constantly switch loyalties. At the beginning he hopes that Janet Leigh won’t be caught. The murder is very shocking, but as soon as Perkins wipes away the traces of the killing, we begin to side with him, to hope that he won’t be found out. Later on, when we learn from the sheriff that Perkins’ mother has been dead for eight years, we again change sides and are against Perkins, but this time, it’s sheer curiosity. The viewer’s emotions are not exactly wholesome.

A.H.: This brings us back to the emotions of the Peeping Tom audiences. We had some of that in Dial M for Murder.

F.T.: That’s right. When Ray Milland was late in phoning his wife and the killer looked as if he might walk out of the apartment without killing Grace Kelly. The audience reaction there was to hope he’d hang on for another few minutes.

A.H.: It’s a general rule. Earlier, we talked about the fact that when a burglar goes into a room, all the time he’s going through the drawers, the public is generally anxious for him. When Perkins is looking at the car sinking into the pond, even though he’s burying a body, when the car stops sinking for a moment, the public is thinking, “I hope it goes all the way down!” It’s a natural instinct.

F.T.: But in most of your films the audience reaction is more innocent because they are concerned for a man who is wrongly suspected of a crime. Whereas in Psycho one begins by being scared for a girl who’s a thief, and later on one is scared for a killer, and, finally, when one learns that this killer has a secret, one hopes he will be caught just in order to get the full story!

A.H.: I doubt whether the identification is that close.

F.T.: It isn’t necessarily identification, but the viewer becomes attached to Perkins because of the care with which he wipes away all the traces of his crime. It’s tantamount to admiring someone for a job well done.

I understand that in addition to the main titles, Saul Bass also did some sketches for the picture.

A.H.: He did only one scene, but I didn’t use his montage. He was supposed to do the titles, but since he was interested in the picture, I let him lay out the sequence of the detective going up the stairs, just before he is stabbed. One day during the shooting I came down with a temperature, and since I couldn’t come to the studio, I told the cameraman and my assistant that they could use Saul Bass’s drawings. Only the part showing him going up the stairs, before the killing. There was a shot of his hand on the rail, and of feet seen in profile, going up through the bars of the balustrade. When I looked at the rushes of the scene, I found it was no good, and that was an interesting revelation for me, because as that sequence was cut, it wasn’t an innocent person but a sinister man who was gong up those stairs. Those cuts would have been perfectly all right if they were showing a killer, but they were in conflict with the whole spirit of the scene.

Bear in mind that we had gone to a lot of trouble to prepare the audience for this scene: we had established a mystery woman in the house; we had established the fact that this mystery woman had come down and slashed a woman to pieces under her shower. All the elements that would convey suspense to the detective’s journey upstairs had gone before and we had therefore needed a simple statement. We needed to show a staircase and a man going up that staircase in a very simple way.

F.T.: I suppose that the original rushes of that scene helped you to determine just the right expression. In French we would say that “he arrived like a flower,” which implies, of course, that he was ready to be plucked.

A.H.: It wasn’t exactly impassivity; it was more like complacency. Anyway, I used a single shot of Arbogast coming up the stairs, and when he got to the top step, I deliberately placed the camera very high for two reasons. The fist was so that I could shoot down on top of the mother, because if I’d shown her back, it might have looked as if I was deliberately concealing her face and the audience would have been leery. I used that high angle in order not to give the impression that I was trying to avoid showing her.

But the main reason for raising the camera so high was to get the contrast between the long shot and the close-up of the big head as the knife came down at him. It was like music, you see, the high shot with the violins, and suddenly the big head with the brass instruments clashing. In the high shot the mother dashes out and I cut into the movement of the knife sweeping down. Then I went over to the close-up on Arbogast. We put a plastic tube on his face with hemoglobin, and as the knife came up to it, we pulled a string releasing the blood on his face down the line we had traced in advance. Then he fell back on the stairway.

F.T.: I was rather intrigued by that fall backward. He doesn’t actually fall. His feet aren’t shown, but the feeling one gets is that he’s going down the stairs backward, brushing each step with the tip of his foot, like a dancer.

A.H.: That’s the impression we were after. Do you know how we got that?

F.T.: I realize you wanted to stretch out the action, but I don’t know how you did it.

A.H.: We did it by process. First I did a separate dolly shot down the stairway, without the man. Then we sat him in a special chair in which he was in a fixed position in front of the transparency screen showing the stairs. Then we shoot the chair, and Arbogast simply threw his arms up, waving them as if he’d lost his balance.

F.T.: It’s extremely effective. Later on in the picture you use another very high shot to show Perkins taking his mother to the cellar.

A.H.: I raised the camera when Perkins was going upstairs. He goes into the room and we don’t see him, but we hear him say, “Mother, I’ve got to take you down to the cellar. They’re snooping around.” And then you see him take her down to the cellar. I didn’t want to cut, when he carries her down, to a high shot because the audience would have been suspicious as to why the camera has suddenly jumped away. So I had a hanging camera follow Perkins up the stairs, and when he went into the room I continued going up without a cut. As the camera got upon top of the door, the camera turned and looked back down the stairs again. Meanwhile, I had an argument take place between the son and his mother to distract the audience and take their minds off what the camera was doing. In this way the camera was above Perkins again as he carried his mother down and the public hadn’t noticed a thing. It was rather exciting to use the camera to deceive the audience.

The Shower Scene: ‘It took us seven days to shoot that scene, and there were seventy camera setups for forty-five seconds of footage. We had a torso specially made up for that scene, with the blood that was supposed to spurt away from the knife, but I didn’t use it. I used a live girl instead, a naked model who stood in for Janet Leigh. We only showed Miss Leigh’s hands, shoulders, and head. All the rest was stand-ins.’F.T.: The stabbing of Janet Leigh was very well done also.

A.H.: It took us seven days to shoot that scene, and there were seventy camera setups for forty-five seconds of footage. We had a torso specially made up for that scene, with the blood that was supposed to spurt away from the knife, but I didn’t use it. I used a live girl instead, a naked model who stood in for Janet Leigh. We only showed Miss Leigh’s hands, shoulders, and head. All the rest was stand-ins. Naturally, the knife never touched the body; it was all done in the montage. I shot some of it in slow motion so as to cover the breasts. The slow shots were not accelerated later on because they were inserted in the montage so as to give the impression of normal speed.

F.T.: It’s an exceptionally violent scene.

A.H.: This is the most violent scene of the picture. As the film unfolds, there is less violence because the harrowing memory of this initial killing carries over to the suspenseful passages that come later.

F.T.: Yes, even better than the killing, in the sense of its harmony, is the scene in which Perkins handles the mop and broom to clean away any traces of the crime. The whole construction of the picture suggests a sort of scale of the abnormal. First there is a scene of adultery, then a theft, then one crime followed by another, and, finally, psychopathy. Each passage puts us on a higher note of the scale. Isn’t that so?

A.H.: I suppose so, but you know that to me Janet Leigh is playing the role of a perfectly ordinary bourgeoise.

F.T.: But she does lead us in the direction of the abnormal, toward Perkins and his stuffed birds.

‘Obviously Perkins is interested in taxidermy since he’d filled his mother with sawdust…’A.H.: I was quite intrigued with them: they were like symbols. Obviously Perkins is interested in taxidermy since he’d filled his own mother with sawdust. But the owl, for instance, has another connotation. Owls belong to the night world; they are watchers, and this appeals to Perkins’ masochism. He knows the birds and he knows that they’re watching him all the time. He can see his own guilt reflected in their knowing eyes.

F.T.: Would you say that Psycho is an experimental film?

A.H.: Possibly. My main satisfaction is that the film had an effect on the audiences, and I consider that very important. I don’t care about the subject matter; I don’t care about the acting; but I do care about the pieces of film and the photography and the sound track and all of the technical ingredients that made the audience scream. I feel it’s tremendously satisfying for us to be able to use the cinematic art to achieve something of a mass emotion. And with Psycho we most definitely achieved this. It wasn’t a message that

stirred the audiences, nor was it a great performance or their enjoyment of the novel. They were aroused by pure film.F.T.: Yes, that’s true.

A.H.: That’s why I take great pride in the fact that Psycho, more than any of my other pictures, is a film that belongs to the film-maker, to you and me. I can’t get a real appreciation of the picture in the terms we’re using now. People will say, “It was a terrible film to make. The subject was horrible, the people were small, there were no characters in it.” I know all of this, but I also know that the construction of the story and the way in which it was told caused audiences all over the world to react and become emotional.

F.T.: Yes, emotional and even physical.

A.H.: Emotional. I don’t care whether it looked like a small or a large picture. I didn’t start off to make an important movie. I thought I could have fun with this subject and this situation. The picture cost eight hundred thousand dollars. It was an experiment in this sense: Could I make a feature film under the same conditions as a television show? I used a complete television unit to shoot it very quickly. The only place where I digressed was when I slowed down the murder scene, the cleaning up scene, and the other scenes that indicated anything that required time. All of the rest was handled in the same way that they do it in television.

F.T.: I know that you produced Psycho yourself. How did you make out with it?

A.H.: Psycho cost us no more than eight hundred thousand dollars to make. It has grossed some fifteen million dollars to date.

F.T.: That’s fantastic! Would you say this was your greatest hit to date?

A.H.: Yes. And that’s what I’d like you to do—a picture that would gross millions of dollars throughout the world! It’s an area of film-making in which it’s more important for you to be pleased with the technique than with the content. It’s the kind of picture in which the camera takes over. Of course, since critics are more concerned with the scenario, it won’t necessarily get you the best notices, but you have to design your film just as Shakespeare did his plays—for an audience.

F.T.: That reminds me that Psycho is particularly universal because it’s a half-silent movie; there are at least two reels with no dialogue at all. And that also simplified all the problems of subtitling and dubbing.

A.H.: Do you know that in Thailand they use no subtitles or dubbing? They shut off all the sound and a man stands somewhere near the screen and interprets all the roles, using different voices.

Hitchcock by Truffaut: The Definitive Study of Alfred Hitchcock is available at www.amazon.com

Alfred Hitchcock’s personal tour of the Psycho mise-en-scene. Hitchcock biographer Patrick McGilligan calls this ‘one of the world’s great trailers.’

***

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024