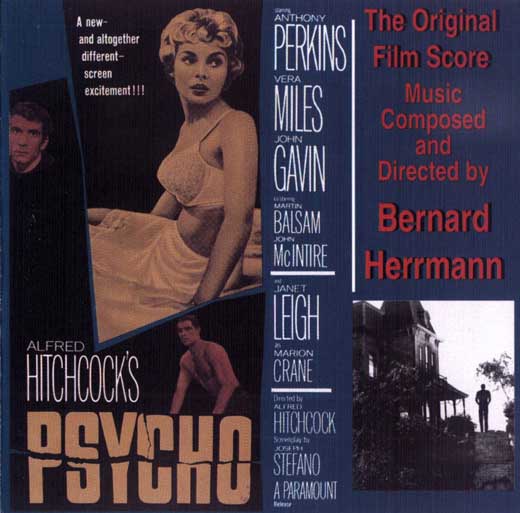

‘A Reflection of A Most Unpleasant Mind’

From vilification to effusive praise, Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho ran the gamut of critical appraisal upon its release on June 6, 1960. A brief history.By Patrick McGilligan

(excerpt from Alfred Hitchcock: A Life In Darkness and Light, ReganBooks, 2003)

Despite controversy everywhere (British censors, for example, gave the film an “X”), Psycho set new attendance records around the world, grossing over $9 million in the United States and another $6 million overseas. In 1960 that remarkable figure was second only to Ben-Hur—and since that film’s budget was $14 million, Psycho was really the year’s most profitable film. (Hitchcock always insisted that he had never envisioned such moneymaking—for him, a “secondary consideration” to making the film.)

Psycho became a genuine phenomenon. Letters to the New York Times debated whether the film was “morbid” and “sickening,” or “superb” and “truly avant-garde.” There were “faintings. Walkouts. Repeat visits. Boycotts. Angry phone calls and letters,” wrote Stephen Rebello. “Talk of banning the film rang from church pulpits and psychiatrist’s offices.”

There was every manner of critical response, including a handful—like Wanda Hale of the New York Daily News—who immediately embraced the film (giving it four stars). More common was the kind of backlash handed out by Dwight Macdonald in Esquire, who vehemently diagnosed Psycho as “a reflection of a most unpleasant mind, a mean, sly, sadistic little mind,” or Robert Hatch in The Nation, who was “offended and disgusted.”

Other critics, unable tomake up their minds, had to see the film more than once and vote both ways. Time thought it was “gruesome,” a heavy-handed “creak-and-shriek movie,” but by 1965 was praising another film, Roman Polanski’s Repulsion as in “the classic style of Psycho.” Similarly, Bosley Crowther of the New York Times, who had been qualified in his reaction to Hitchcock’s films for over two decades, initially described Psycho as unsubtle and even “old-fashioned”; but the controversy over the film led him, as he had done with Lifeboat almost twenty years earlier, to reappraise the Hitchcock film in a Sunday piece—this time upgrading his opinion (Psycho was now “fascinating” and “provocative”). By the end of the year, the New York Times critic had decided Psycho was among the year’s Ten Best, describing it variously as “bold,” “expert,” and “sophisticated.”

One perceptive assessment came from V.E. Perkins, writing in England’s Oxford Opinions. Reacting to Sight and Sound’s verdict that Psycho was “a very minor work,” Perkins diagnosed, and prescribed, repeated viewing to prove his thesis. “The first time it is only a splendid entertainment, a ‘very minor film,’ in fact,” Perkins wrote. “But when one can no longer be distracted from the characters by an irrelevant ‘mystery’ Psycho becomes immeasurably rewarding as well as much more thrilling.” Perkins went on to praise the “spectacularly brilliant” acting and “layers of tension” in the film, concluding that the subject matter was “fit only for a tragedian. And that is what Hitchcock finally shows himself to be.”

Up to that time no film boasted as many return viewings. Psycho capped ten years of sustained creativity for Hitchcock. And, along with his other 1950s films that crisscrossed a dangerous land, it showed him to be an American tragedian indeed—tragedy delivered, as always, with a wink.

Patrick McGilligan’s Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light is available at www.amazon.com

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024