‘I Want To Be Remembered As One Who Tried’

Dorothy Height

‘Godmother of the Civil Rights Movement’

March 24, 1912-April 20, 2010Dorothy Height, recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom Award in 1994, and the leading female voice of the 1960s civil rights movement, who first taught, and then participated in historic marches with, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., died on April 20 at Howard University Hospital in Washington, D.C., where she had been admitted, for unspecified reasons, on March 25. She was 98.

Height, whose activism on behalf of women and minorities dated to the New Deal, led the National Council of Negro Women for 40 years. As a professor at Atlanta’s Moorehouse College in 1945, she met and taught the young Martin Luther King, Jr., then an outstanding 14-year-old enrolled in the school’s gifted student program. She continued actively speaking out into her 90s, often getting rousing ovations at events around Washington, where she was immediately recognized by the bright, colorful hats she almost always wore.

In a statement, President Barack Obama called her "the godmother of the civil rights movement" and a hero to Americans.

‘Dr. Height devoted her life to those struggling for equality,’ President Obama said upon learning of Dr. Dorothy Height’s death"Dr. Height devoted her life to those struggling for equality...and served as the only woman at the highest level of the Civil Rights Movement—witnessing every march and milestone along the way," Obama said.

As a teenager, Height marched in New York's Times Square shouting, "Stop the lynching." In the 1950s and 1960s, she was the leading woman helping King and other activists orchestrate the civil rights movement, often reminding the men heading the movement not to underestimate their female counterparts.

One of Height's sayings was, "If the time is not ripe, we have to ripen the time." She liked to quote 19th century abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who said that the three effective ways to fight for justice are to "agitate, agitate, agitate."

Height was on the platform at the Lincoln Memorial, sitting only a few feet from King, when he gave his "I have a dream" speech at the March on Washington in 1963.

Dr. Dorothy Height discusses the impact of the Supreme Court’s ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) outlawing segregation on public schools: ‘What was done in Brown was not a benefit to the black community, but to the black community and the white community.’She lamented that the feeling of unity created by the 1963 march had faded, and that the civil rights movement of the 1990s was on the defensive and many black families were still not economically secure.

"We have come a long way, but too many people are not better off," she said. "This is my life's work. It is not a job."

When Obama won the presidential election in November 2008, Height told Washington TV station WTTG that she was overwhelmed with emotion.

"People ask me, did I ever dream it would happen, and I said, 'If you didn't have the dream, you couldn't have worked on it,’" she said.

Height became president of the National Council of Negro Women in 1957 and held the post until 1997, when she was 85. She remained chairman of the group.

She received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1994 from President Bill Clinton.

In a Nov. 19, 1964 file photo, from left, James Farmer, national director of the Congress of Racial Equality; Whitney M. Young, Jr., executive director of the National Urban League; Dorothy Height of the National Council of Negro Women, talk to reporters in Washington D.C. after meeting with President Lyndon Johnson.To celebrate Height's 90th birthday in March 2002, friends and supporters raised $5 million to enable her organization to pay off the mortgage on its Washington headquarters. The donors included Oprah Winfrey and Don King.

Height was born in Richmond, VA, and the family moved to the Pittsburgh area when she was four. She earned Bachelor's and Master's degrees from New York University and did postgraduate work at Columbia University and the New York School of Social Work. (She had been turned away by Barnard College because it already had its quota of two black women.)

In 1937, while she was working at the Harlem YWCA, Height met famed educator Mary McLeod Bethune, the founder of the National Council of Negro Women, and first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who had come to speak at a meeting of Bethune's organization. Height eventually rose to leadership roles in both the council and the YWCA.

‘As women we will always have to stand up and speak for ourselves’: Dorothy Height, chair and president emeritus of the National Council of Negro Women, reflects on her life and the changes in society’s attitudes towards women during the Civil Rights era.The late activist C. DeLores Tucker once called Height an icon to all African-American women.

"I call Rosa Parks the mother of the civil rights movement," Tucker said in 1997. "Dorothy Height is the queen."

Dr. Dorothy Height’s memoir, Open Wide The Freedom Gates, is available at www.amazon.comFilm historian and political writer William Hare of Seattle, WA, posted this online book review at Amazon.com:

Dorothy Height carries the strength of granite and a backbone resolute with meaningful purpose. Growing up in suburban Pittsburgh, Height, now 91 and still busily at work, saw discrimination and never flinched, determined to meet adversity with an agile brain, a strong body, and an indomitable will.As a high school girl she won an impromptu speech competition at the county level, then was forced to confront the ugly tentacles of segregation when she sought to find a place to stay as she competed in the finals in the Pennsylvania capital of Harrisburg. She learned that she was the only African-American in the competition. When she sought a drink of water prior to her speech, it was the only other person of color in the building, an African-American janitor, who escorted her to the drinking fountain. Height won the competition by tying her speech theme, the Kellogg-Briand Peace Treaty, to efforts of the black race to overcome adversity. She explained to an enthralled audience that, just as peace can only be accomplished through purposeful unity, such is also the case with respect to the races. Height won that competition.

After achieving straight A's at New York University, Height went to work for the YWCA in Manhattan. This was the beginning of a stellar career that took her to the pinnacle of African-American leadership in the women's movement, and ultimately led to a Presidential Medal of Freedom and a Citizenship Award conferred on her by President Ronald Reagan in 1989. Height refers to two strong women of principle and achievement who served as role model beacons for the bright and enterprising young woman. First lady Eleanor Roosevelt was someone she would admire and come to know well. Her other major influence was the daughter of slaves, the remarkable Mary McCleod Bethune, who would overcome a painful asthma condition to become a leading achiever for women of all races, and who founded a college, Bethune-Cookman in Daytona Beach, Florida.

As a professor at Moorehouse College in Atlanta in 1945, Height met and taught a remarkable 14-year-old as part of the school's gifted student program. She saw the promise in young Martin Luther King and was by his side at the 1963 March on Washington organized by prominent labor leader A. Philip Randolph, the president of the sleeping car porters' union,with whose vision for racial progress she synchronized.

In terms of the present, Height sees the Democratic Party as taking African-Americans for granted and Republicans of being neglectful of their needs and aspirations except when it serves their purposes to be attentive. All the same, rather than lament conditions, she remains the eternal pragmatist. She realizes that the road to progress can be best realized in the way that the great A. Philip Randolph outlined, by uniting and working diligently to achieve purposeful goals, by lighting candles rather than cursing darkness.

***

Dr. Dorothy Height: In Her Own Words

If you worry about who is going to get credit, you don't get much work done.

Greatness is not measured by what a man or woman accomplishes, but by the opposition he or she has overcome to reach his goals.

I was inspired by Mary McLeod Bethune, not only to be concerned but to use whatever talent I had to be of some service in the community.

As I reflect on the hope and challenges facing women in the 21st century, I am also reminded of the protracted struggles of African-American women who joined together as sisters in 1935 in response to Mrs. Bethune's call. It was an opportunity to deal creatively with the fact that Black women stood outside of America's mainstream of opportunity, influence and power.

I want to be remembered as someone who used herself and anything she could touch to work for justice and freedom.... I want to be remembered as one who tried.

A Negro woman has the same kind of problems as other women, but she can't take the same things for granted.

As more women enter public life, I see developing a more humane society. The growth and development of children no longer will depend solely upon the status of their parents. Once again, the community as the extended family will rekindle its caring and nurturing. Though children cannot vote, their interests will be placed high on the political agenda. For they are indeed the future.

1989, about using the term "black" or "African American": As we move ahead into the 21st century and look at a unified way of fully identifying with our heritage, our present and our future, our use of African-American is not a matter of putting down one to pick up the other. It is a recognition that we've always been African and American, but we are now going to address ourselves in those terms and make a unified effort to identify with our African brothers and sisters and with our own heritage. African-American has the potential of helping us to rally. But unless we identify with the full meaning, the term won't make a difference. It becomes merely a label.

When we started using the term 'Black,' it was more than a color. It came at a time when our young people in marches and sit-ins made they cry 'Black Power.' It represented the Black experience in the United States and the Black experience of those throughout the world who were oppressed. We are at a different point now. The struggle continues, but it's more subtle. Therefore, we need, in the strongest ways we can, to show our unity as a people and not just as a people of color.

It was not easy for those of us who had become symbols of the struggle for equality to see our children raising their fists in defiant contradiction of all we had fought for.

No one will do for you what you need to do for yourself. We cannot afford to be separate.

We have to see that all of us are in the same boat.

But we're all in the same boat now, and we've got to learn to work together.

We are not a problem people; we are a people with problems. We have historic strengths; we have survived because of family.

We have to improve life, not just for those who have the most skills and those who know how to manipulate the system. But also for and with those who often have so much to give but never get the opportunity.

Without community service, we would not have a strong quality of life. It's important to the person who serves as well as the recipient. It's the way in which we ourselves grow and develop.

We've got to work to save our children and do it with full respect for the fact that if we do not, no one else is going to do it.

There is no contradiction between effective law enforcement and respect for civil and human rights. Dr. King did not stir us to move for our civil rights to have them taken away in these kinds of fashions.

The Black family of the future will foster our liberation, enhance our self-esteem, and shape our ideas and goals.

I believe we hold in our hands the power once again to shape not only our own but the nation's future — a future that is based on developing an agenda that radically challenges limitations in our economic development, educational achievement and political empowerment. Undoubtedly, African-Americans will have an integral role to play, although our path ahead will continue to be complex and difficult.

As we move forward, let us also look back. So long as we remember those who died for our right to vote and those like John H. Johnson who built empires where there were none, we will walk into the future with unity and strength.

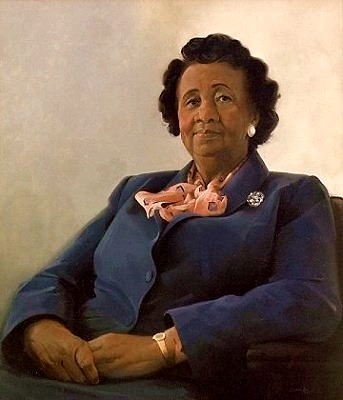

The official portrait of Dr. Dorothy Height, National Council of Negro Women, oil on linen

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024