George Gershwin, a self portraitFathers And Sons

By David McGeeNo, we’re not talking Ivan Turgenev (our tribute to Russian authors is confined in this issue to Leo Tolstoy), but rather real fathers and sons, and memorable reactions of one to the other.

New York City, 1924. George Gershwin, then 26, having studied with classical composer Rubin Goldmark and avant-garde composer-theorist Henry Cowell; worked as a song plugger for a New York music publishing company; recorded an untold number of piano rolls under his own and assumed names; taken a shot at vaudeville; and partnered with lyricist Buddy DySylva on a one-act jazz opera, Blue Monday (which turned out to be the template for Porgy and Bess)—after all this, he had composed a classical-jazz work for orchestra and piano, titled “American Rhapsody.” At the suggestion of his brother Ira, who had been impressed by an exhibition of paintings by James McNeil Whistler with titles such as “Nocturne in Black and Gold” and “Arrangement in Grey and Black,” George changed the title to “Rhapsody in Blue.”

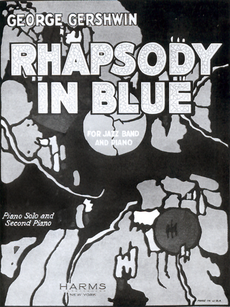

Original sheet musicThe composition had started taking shape in Gershwin’s head while the composer was on a train trip to Boston. To his first biographer, Isaac Goldberg, he explained: “It was on the train, with its steely rhythms, its rattle-ty bang, that is so often so stimulating to a composer—I frequently hear music in the very heart of the noise... And there I suddenly heard, and even saw on paper—the complete construction of the Rhapsody, from beginning to end. No new themes came to me, but I worked on the thematic material already in my mind and tried to conceive the composition as a whole. I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our blues, our metropolitan madness. By the time I reached Boston I had a definite plot of the piece, as distinguished from its actual substance.”

Commencing work on January 7, 1924, Gershwin completed the composition on February 4, eight days before its scheduled premiere “An Experiment in Modern Music,” a concert presented by Paul Whiteman and the Palais Royal Orchestra at Manhattan’s Aeolian Hall on 42nd Street (now home to the State University of New York’s State College of Optometry).

Before the folks at Aeolian Hall heard “Rhapsody in Blue,” however, its first audience was Gershwin’s father, Morris (Moishe) Gershowitz (George was born Jacob Gershowitz on September 26, 1898).

When he had finished playing the entire composition on piano, George inquired of his father’s reaction to the piece.

Sayeth Moishe: “I never thought I would raise a son who would write a piece of music that lasts longer than 18 minutes.”

Reviews of “Rhapsody” were decidedly mixed. The New York Times’s Olin Downes gave it a lukewarm appraisal, praising the composer’s imagination and ambition; downgrading it on technicalities (“Tuttis are too long, cadenzas are too long, the peroration at the end loses a large measure of the wildness and magnificence it could easily have had if it were more broadly prepared…”); but noting “tumultuous applause” by the audience. In the New York Tribune, Lawrence Gilman was less sanguine: “How trite, feeble and conventional the tunes are; how sentimental and vapid the harmonic treatment, under its disguise of fussy and futile counterpoint! ... Weep over the lifelessness of the melody and harmony, so derivative, so stale, so inexpressive!” Even 31 years later, in 1955, the well-established and beloved “Rhapsody” was drawing critics’ ire. Writing in the Atlantic Monthly that year, none other than Leonard Bernstein observed: “The “Rhapsody” is not a composition at all. It's a string of separate paragraphs stuck together. The themes are terrific—inspired, God-given. I don't think there has been such an inspired melodist on this earth since Tchaikovsky. But if you want to speak of a composer, that's another matter. Your ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ is not a real composition in the sense that whatever happens in it must seem inevitable. You can cut parts of it without affecting the whole. You can remove any of these stuck-together sections and the piece still goes on as bravely as before. It can be a five-minute piece or a twelve-minute piece. And in fact, all these things are being done to it every day. And it's still the ‘Rhapsody in Blue.’”

‘Rhapsody in Blue,’ Leonard Bernstein, conductor and piano master, Royal Albert Hall, 1976. Part 1.

‘Rhapsody in Blue,” Leonard Bernstein, part 2.

***

'I Never Met A Songwriter Before'

Gerald Marks, born October 13, 1900, in Saginaw, Michigan, began composing songs in the 1920s, for films and Broadway shows. Al Jolson’s “Is It True What They Say About Dixie” is one of his classics, but by far his most famous and enduring tune is “All Of Me,” written (with Seymour Simon) in 1931 and recorded some 2,000 times by some of the most important artists in popular music history—Billie Holiday (with Lester Young on tenor sax), Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong, Sarah Vaughan, Django Reinhardt, et al. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/All_of_Me_(song)—a true monument of the Great American Songbook.

But Gerald Marks never knew his father, who abandoned the family when his son was a toddler. Some years after “All Of Me” had brought him a measure of fame and financial security, Marks was traveling cross-country by rail. At a stop in St. Louis, while sitting in the waiting room prior to starting the next leg of his journey, he looked up to see a man across the room, also on his way to somewhere else and passing the time before his departure.

“I was looking at a mirror image of myself, only a little older,” Marks told me during one of our many conversations over the last 15 years of his life (he died in 1997).

Their eyes met as Marks approached the dapper-dressed fellow.

“Father?” he asked.

The immediate, bloodless response: “Yes.” Followed by an invitation for Gerald to join him on the bench.

“So, son, what have you done with your life?”

The younger Marks explained himself, told him how he had left school to pursue a songwriting career, about “All Of Me,” Al Jolson, and the art he had devoted himself to.

“How about that?” the senior Marks said evenly. “I never met a songwriter before.” Rising to his feet, he walked away.

Gerald Marks never saw his father again.

The Berger-Marks Foundation, created in 2003 and named after Marks and his wife Edna Berger, the first female organizer for The Newspaper Guild, helps organize women into unions. Ms. Berger predeceased her husband by one year, in 1996. Gerald Marks left three-quarters of his estate to the Foundation.

A western swing version of ‘All Of Me’ by double-Grammy nominees The Time Jumpers, a contingent of top-drawer Nashville sessions players who regularly hold forth at Nashville's Station Inn. Regular members include Dennis Crouch (bass), Danny Parks (guitar), Aubrey Haynie (fiddle), among others, and Vince Gill has been known to sit in from time to time. This selection features one of the outstanding vocalists in country music, Dawn Sears, taking the lead. Next to her is the late Carolyn Martin. The impeccable steel solo is by a giant of the instrument, John Hughey, whose resume http://www.johnhughey.com/resume.html would take up most of this issue and is required reading for any serious country fan. Mr. Hughey passed away on November 18, 2007.

Founder/Publisher/Editor: David McGee

Contributing Editors: Billy Altman, Laura Fissinger, Christopher Hill, Derk Richardson

Logo Design: John Mendelsohn (www.johnmendelsohn.com)

Website Design: Kieran McGee (www.kieranmcgee.com)

Staff Photographers: Audrey Harrod (Louisville, KY; www.flickr.com/audreyharrod), Alicia Zappier (New York)

E-mail: thebluegrassspecial@gmail.com

Mailing Address: David McGee, 201 W. 85 St.—5B, New York, NY 10024